[...]

So did the earth

make you,

onion,

clear as a planet,

and destined

to shine,

constant constellation

round case of water,

upon

the table

of the poor.

Generously

you undo

your globe of freshness

in the fervent consummation

of the cooking pot

and the crystal shred

in the flaming heat of the oil

is transformed into a curled golden feather.

Then, too, I will recall how fertile

is your influence

on the love of the salad,

and it seems that the sky contributes

by giving you the shape of hailstones

to celebrate our chopped brightness

on the hemispheres of a tomato.

But within reach

of the hands if the common people,

sprinkled with oil,

dusted

with bit of salt,

you kill the hunger

of the day laborer on his hard path.

Star of the poor,

fairy godmother

wrapped

in delicate

paper, you rise from the ground

eternal, whole, pure

like an astral seed.

And when the kitchen knife

cuts you, here arises

the only tear

without sorrow. [...]

Pablo Neruda, Ode to the Onion

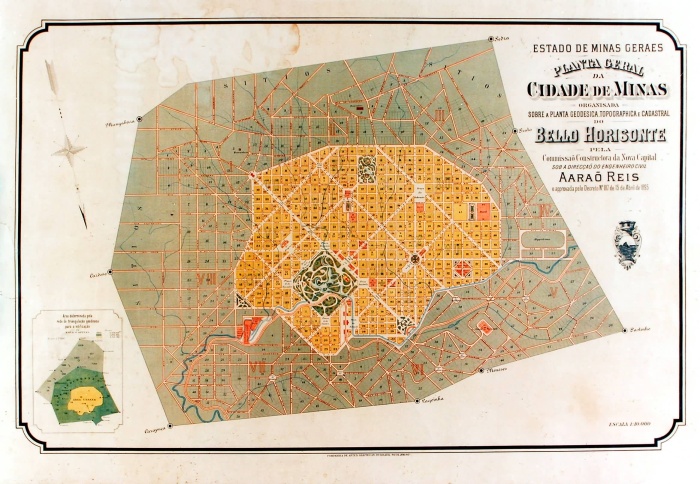

Plan miasta Belo Horizonte, 1895. Żródło: wikicommons

In the turbulent 1990s, the first protests against the Deputy Prime Minister Leszek Balcerowicz’s neoliberal policies intended to transform the economy swept through Poland; as it turned out, there was a massive increase in unemployment, and extensive privatization that resulted in the annihilation of part of Polish industry almost overnight. At one of the demonstrations, the anarchists who had organized the event, countered the prevalent government battle cry of the time urging Poland to catch up with the West, with a slogan of their own: “We shall be another America... But Latin America.”

In Poland, we like to think of ourselves as belonging to “the West” – from which we only became separated for a period of our history, during the communist days, soon to return to the fold. This perspective gives us solace and satisfaction, a sense of pride and security, because in every possible way, it is good to be part of the best of all possible worlds. But we have never been a part of it. In the global capitalist system, our position, status, potential, and perspectives are indeed closer to those of Latin America. This is a perspective that is hard to swallow, both against the backdrop of our awakened ambition, myths, and heartwarming promises, and the fact that in the Polish academic and public discourse – and in particular in economics and pop economics, and liberal and neoliberal theories – the dominant vision is that of imitation: that, if we do as they do in the West, than one day, we shall be as the West is. This, however, is a myth, or rather, as the classics of Marxism would have it, an idea propagated by the ruling classes – ideas beneficial to those classes and representing their interests. And no more than that.

***

And here is another inconvenient truth: in certain respects, Latin America is doing better than Poland. For one thing, an awareness prevails throughout the continent that throughout history, its development has not been equal to that of the “West” and it is therefore impossible to catch up with it in the present scheme of things – or ever, without a drastic destabilization of the world order, or through mindless imitation of the West. It was in the countries of the region that the most significant intellectual efforts were made to further the understanding of the vicious circle that results from the dependence of the periphery on the core. The starting point was the dilemma that has prevailed in the countries of Central and Latin America, and which can be expressed most simply in the question: why are we still poor and backwards, since we have long achieved independence and, at least theoretical, sovereignty, and in many areas we have made scrupulous efforts to emulate the rich countries?

This is the question that informs the work of the Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL), founded in 1948. Since 1950 it has been managed by Raúl Prebisch, who, as part of the broadly conceived analytical trend, Latin American structuralism, has made the terms “peripheral economy” and “peripheral capitalism” into intellectual currency. Thus, a new intellectual and economic movement was created, known as “dependism.” Inspired by Western left-wing thought – including the radical, such as the concept of imperialism created by Rosa Luxemburg – yet rejecting the eurocentrism of the main drift of socialist thought, it has developed a doctrine that criticizes the imitative vision of industry and economy. It concludes that there is no simple linkage between imitating the West and attaining its standard of living. This does not mean that a partial improvement is not possible in some poorer regions of the globe, where the standard of living of the local population will rise in step with the progression of capitalism. There are, however, no prospects in the existing situation and the realities of the imitative developments to alter in a significant way the existing disproportions, level of development and quality of life between the two blocs. This is a zero-sum game: the development of the countries of the core to a large extent depends on the underdevelopment and exploitation of the peripheral countries and regions.

This trend, which originated in the Latin American countries, soon inspired an intellectual critique in the West. This resulted in comprehensive new theories (Wallerstein’s “world system”), as well as research probing well into the past. The origins of the progress of a few countries but backwardness of others have been sought in the pre-modern era. For Poland, this was the strengthening and expansion of the farming and feudal economy, which originally proved profitable for the élites, but ultimately made the country fall behind the West, which embarked on a modernization of its economic system, also thanks to cheap Polish agricultural resources. This analytical approach was also favored by researchers in the real socialist camp – in Poland, with the researchers Oskar Lange, Ignacy Sachs, Witold Kula, and Henryk Szlajfer) – who tried to understand the reasons why the country and region had been apparently forever doomed to be backward in comparison with the West; they aimed to identify the possible ways out of the impasse.

***

Since 1989, the triumph of neoliberal ideology and imitative visions of capitalism in Poland mean that there is almost no reflection on these issues. Even in critical circles on the left it is almost non-existent, unless – at best – as a reference to the theoretical conclusions of, say, Immanuel Wallerstein, which are in any event set aside as regards local analysis. Occidentalism, a pro-European stance and an almost uncritical, total enchantment with the West (with the exception of the USA, as a result of anti-American left-wing attitudes) – all these overshadow any nuances and do not allow one to apply to Polish reality the doubts that arise when considering other countries. One example is the situation, where the same circles noted and criticized the brutal policies of the European Union, in particular those of Germany and the Troika towards Greece and other southern European countries, whilst at the same time employing a naïve “europeanism” for sake of their internal politics.

The same applies of course, and perhaps to an even greater degree, to most of the Polish right, whose ruminations about sovereignty (because dependism is pivoted on sovereignty – albeit not necessarily reduced to the confines of a nation-state – rather than a left-wing stance) seem tainted with socialism. In turn, the right’s postulates about sovereignty are directed at the European Union, almost completely ignoring the USA or Britain. This attitude is related to the past and the association of the phraseology and the circles supporting the interests of peripheral countries with communism. As a result, the Polish right totally overlooks the fact that the government of Salvador Allende, for example, and his reforms were not only socialist, and entirely unconcerned with gaining access to the Soviet camp, but were, rather, an attempt at a partial change for the better in the situation in that peripheral country. In turn, Pinochet’s coup was a return to the position of a subservient peripheral country that totally accepted the hegemony of the core and its interests, only seeking a small part of the cake to satisfy the private interests of the home compradores. The situation was similar in Cuba, where Castro and Guevara had nothing in common with communism at the point of embarking on armed struggle. Theirs was a national independence movement in a peripheral country that wanted more sovereignty – let us note that the local pro-Kremlin communists referred to their revolution as a foolhardy putsch and disowned its participants. It was only the interference of the USA, conducted with a view to the continuation of the exploitation of a peripheral country by the core that pushed the leaders of the new Cuba into the embrace of the Soviet empire – distant, thus perceived as more idealistic and less dangerous than the United States, with which it was in conflict. This also worked in a different way. As Wojciech Giełżyński noted many years ago in his book on the revolution in Nicaragua, “Zbigniew Brzeziński wrote in Foreign Policy that if governments in Central America are indifferent to the growing demand for social justice and respect for national dignity, this will only be to the advantage off Fidel Castro.”1

Ideologies and flag-waving are secondary to attempts to overcome neo-colonial dependency, and the countries of the region are endeavoring to repeat what the current hegemon used to do when in a similar situation: “[...] the American revolution that resulted in the birth of the United States as an independent country, at the time of its eruption was simply a protest of the people against the theft carried out by English trading companies. The mechanism of the theft was as follows: raw materials, bought for pennies in America, went to England and returned as finished products at usurious prices [...]’, wrote Oskar Lange.2 And he added, this time in reference to the formally independent, post-colonial territories of his era: “The economic benefits of [...] foreign capital are [...] very limited. In fact, it transforms backward countries into a hinterland, a raw materials-cum-agriculture supply zone for the metropolis, [...] draining the primitive countries of part of the produced value added. [...] Thus, foreign capital basically is not a factor that could break through the country’s backwardness but rather supports this state through a one-sided orientation towards an economy based on resources and mining and through siphoning off some of the value added that had been produced in that country.”3

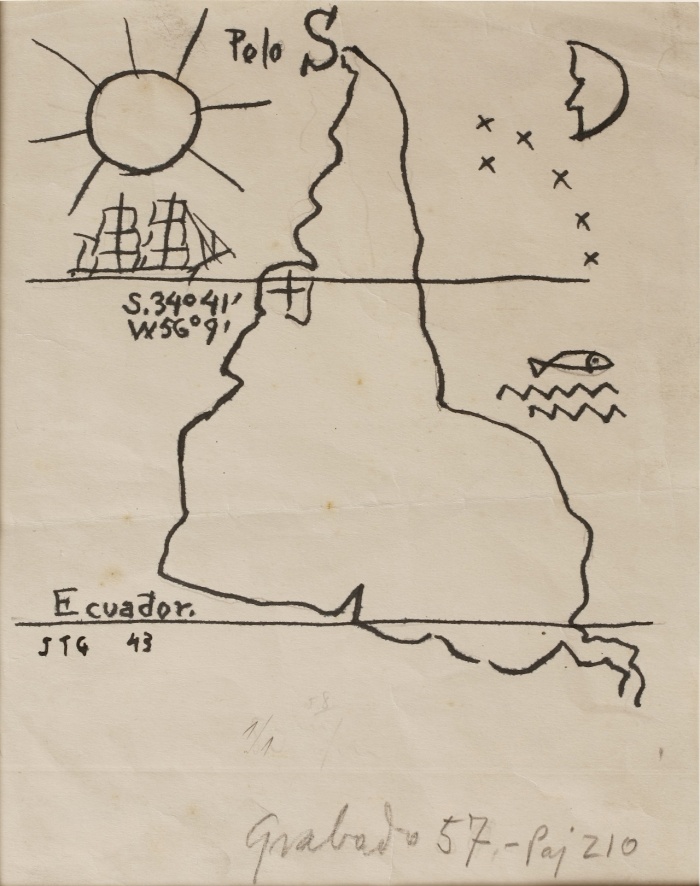

Joaquín Torres-García, “América invertida (Ameryka odwrócona)” (1943), atrament na papierze, 8 11 16 × 6 5 16 cali. Museo Torres García, Montevideo (© Sucesión Joaquín Torres-García, Montevideo 2015)

Of course, since the Polish economist wrote these words, some of the conditioning has changed. The development and lowering cost of transport as well as the process of shifting industries into poorer countries – because of the lower cost of labor and natural resources as well as less adherence to environmental protection and a greater acquiescence in “dirty” industries – have changed the structure of some peripheral countries, bringing industrial development and, to an extent, even a transfer of technology. Notwithstanding the fact that this impact has been limited, with only some contributions from the most modern solutions, these countries have ceased to be solely providers of industrial resources and agriculture to service the core. All the same, no significant changes have taken place in the mechanism of dependence and trade exchange, working to the disadvantage of, and draining, the periphery. Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Enzo Faletto, once prominent dependist thinkers, who later mellowed considerably in their judgment, in their acclaimed book Dependency and Development in Latin America, expanded on the phenomenon that, in spite of the inflows of foreign capital from countries with a higher level of industrialization, the situation in the periphery did not result in a significant growth of the co-indices of development there, due to the fact that both capital and the control of industrial decisions were part of the dependent economy and served to increase the capital in the core.4

Formulaic labels are of little use in the analysis of events in Latin American countries. In these countries, the sovereign right and politically hybrid circles employed the slogans and goals traditionally of the left. One such political and ideological hybrid was the Argentinian leader Juan Perón and the entire movement that he inspired. The military coup in Peru in 1968 was conducted under the banners of sovereignty, order, a strong state, and a break with “corrupt democracy” – in other words, in the name of a vision that had more in common with the right than the left. It was only the reality of the government in a poor, dependent country, including pressure from abroad, that brought about an evolution of the regime towards the left as well as considerable social reforms.

This was a characteristic trait of the many “national revolutions” in the countries of Latin America – organized and led by national elites and pushed aside into a secondary role by the native compradores and “governors” sent in from the countries of the capitalist core to run business and administration – in time they became inclusively democratic, or else postulated one form of socialism or another. Firstly, a decisive factor was the coming into contact with the reality of mass poverty and its social and economic effects such as low purchasing power, lack of qualified personnel, educational backwardness, and lack of national awareness. These movements sought mass popular support against the many forms of resistance against the transformations taking place, whether on the part of the opposition defending the status quo, or various pressures from abroad. All this tended to push the “national revolutions” even further to the left – in the direction of the interests of mass society, as well as criticism of foreign pressure and the impact of the capitalist core. Tadeusz Łepkowski described this process very well in relation to the early drives for sovereignty in the region. Later, the situation was similar: “Hispanic American independence revolutions were politically limited, mostly élite movements [...]. It was impossible, [however] to contain them within a narrow circle of rich insiders. Of necessity, the revolution touched the entire population, becoming a social movement; new motivations appeared, and goals were set that were different from those originally adopted by those who had initiated the independence movements.”5

Despite the fact that these countries soon became independent, they experienced a profound sense of dependence for decades after attaining sovereignty. For this reason, in Latin America – unlike in Europe – the terms “socialism” and "patriotism,” and even “nationalism,” were frequently used interchangeably, because they meant both an actual national government from within the country and the removing of the shackles of the masses. These were the shackles of exploitation in a system still akin to the feudal, where the land owners were “collaborators” with the distant core, embroiled in dependent deals involving exports of agricultural products and materials and imports of luxury goods – deals that were profitable for them personally but damaging for the country. For this reason, when Fidel Castro – at the time, not yet a communist but a fighter for national independence – spoke at his trial after the failed attack on the Moncada barracks, he addressed this lack of real national independence directly: “More than half of our most productive land is in the hands of foreigners. In Oriente, the largest province, the lands of the United Fruit Company and the West Indian Company link the northern and southern coasts. There are two hundred thousand peasant families who do not have a single acre of land to till to provide food for their starving children. [...] Cuba continues to be primarily a producer of raw materials. We export sugar to import candy, we export hides to import shoes, we export iron to import ploughs...”6 If one were to change the geographic details and names of businesses, substituting them with more recent products and resources, and of course pass in silence over the “forbidden” name of the orator, one might think that these accusatory words had been spoken by one of the Polish popular-nationalist radicals of the 1990s or a decade later.

Once, also a part of the Polish left had no doubts about the country’s economic position vis-à-vis the capitalist core countries. For example this is what Andrzej Stawar, first an orthodox communist and later a Trotskyist "heretic," wrote in 1927: "Capitalism in Poland has certain features of semi-colonial capitalism, if not in formal terms than certainly significant. [...] What matters is not only the direct exploitation by foreign capitalists (for instance through exporting a percentage of the capital) but also above all the disequilibrium of the economic forces of a country less industrially developed in comparison with a stronger trading partner, which leads to exploitation.”7 This conclusion mirrors almost word for word those reached by the dependency theorists in Latin America: the realization that the exploitation of the dependent – although apparently independent – territories is carried out by specific companies or multinationals or holdings but it is part of a comprehensive system of exploitation. The crux is the lack of equilibrium between the participant countries in the transaction, whether related to production and investment or to trade. The large and powerful country will of course get further than a small and weak one. Moreover, Stawar formulated a thesis that both then and now has shocked many readers: in the countries of our region (Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Rumania) trade and industrial relations with the West have not so much stimulated local development as resulted in…regression: the “influence of the West strengthened and preserved some of the features of feudalism.”

***

Quite early on, Latin American visions of sovereignty began to include ecological themes. It was not coincidental that this topic became of interest: the exploitation of the periphery by the core is related to, among others, natural resources and, ever since the West had become aware of the need to protect the environment, it had had a tendency to dump “dirty” industries in the periphery, since it is possible to treat these territories as a source of natural products and raw resources without the need to pay attention to the environment or the health of the workers and general population, now or in the future, leaving them with environmental pollution, rubbish, and obsolete factories.

The benefits to the periphery country are scant – the majority of the profits go to the foreign companies or the narrow local comprador élites, natural goods are ruthlessly processed and depleted, and the country becomes an exporter of unprocessed products using old-fashioned technology, industrial solutions, and methods of organization. The natural environment shrinks due to ruthless transformation and exploitation with little benefit to the local population or to its detriment, with disappearing forests, adverse changes in the microclimate, environmental pollution, depletion of resources, a negative impact on health, and so on. Whereas the brutal transformation of the natural environment in the core countries during the industrial revolution had resulted in a relatively rapid and significant improvement in the general standard of living and, in due course, had led to numerous “green” solutions, the same is not true about the periphery countries, doomed to suffer the negative effects of overexploitation. No wonder that ecology has featured strongly in various Latin American visions of freeing the periphery from the pernicious oppression of the core. The myths, beliefs, and cosmogony of the native Indian tribes played a role here, together with equality of the native peoples – another axiom of local movements and ideologies. The entire exploitative model of Western civilization became the object of criticism. Celso Furtado, Brazil’s most renowned economist, theoretician of dependency, and thinker, noted as early as the 1970s, that the price of such a world system, relying heavily on the destruction of the natural environment is so high, that if it were to become prevalent, it could lead to the downfall of our entire civilization and put a question mark over the survival of the human race.

***

Practice proved harder than theory. While the countries of Latin America succeeded relatively well, if partially and temporarily, in getting rid of the direct or more subtle dependency on the capitalist core, they soon faced a problem: what should be the basis of the development of their industry and economy, which would allow them to accumulate capital and repair the national budget and foreign trade balance? The easiest, quickest, and most profitable solution was through the exploitation of nature. When Marcin Kula described the fiasco of the Bolivian “national revolution,” in spite of his sympathetic approach, he could find little to praise, concluding that “one of the few positive phenomena in the development of post-revolutionary Bolivia was the rise in oil extraction – within a decade increasing by almost 600 percent.”8

Let us not be glib in condemning this too quickly. First of all, ecological awareness is a new phenomenon; in the West – the part of the world best financially equipped to tackle the issue but also endowed with generously funded academic and research centers and media – it was only in the 1960s and 1970s that this topic gained popular exposure, and even so, this did not lead immediately to widespread ecological action. Secondly, for the rich countries, concern for their ecology often meant outsourcing non-green technologies and methods of production precisely to the periphery, which soon became the go-to source for many common products, as long as they were cheap to transport. The “carbon footprint” of Western societies, or the index of CO2 emission calculated for the majority of goods and services used by the average consumer leaves no room for delusion in this matter. Although there are not many “dirty” factories left in the rich countries, these countries avail themselves of numerous goods produced all over the world in just such factories; as a consequence, the overall environmental impact of “clean” societies is much higher than of the ecologically unaware.

Thirdly, and most importantly, the periphery countries often have nothing more to offer apart from the exploitation and export of the natural resources. For decades, their economies have been oriented towards just such a mode of functioning, exporting cheap unprocessed goods and resources, including agricultural produce, and importing luxury goods for their élites and processed goods for the rest of society, since they lacked the means to produce them themselves.

Jeden z zachowanych kadrów zaginionego filmu Goldlust (1986), przedstawiającego pracę w największej dzikiej kopalni świata, Serra Pelada (Naga góra) w stanie Pará w Brazylii. Źródło: wikicommons

Hence, one of the key postulates and political decisions of the dependists was the substitution of imports – the development of a broad and diverse national base of production in order to curtail imports and break out of the vicious circle of the dependency of the industrial structure on the model of export oriented, simple, almost “natural” production. As it happens, the rise of the green movements coincided with the rise of neoliberalism, which relied on the exploitation of the natural resources of the periphery and restriction of environmental protection, putting short-term profits above non-material, long-term gain. It encouraged the stimulation of consumption, often wasteful in terms of the responsible husbandry of rare and non-renewable resources. In Latin America, the Amazon rainforest became a notorious symbol of such practices – its globally unique vast resource of biodiversity has been drastically and progressively devastated. It was not, however, sovereign governments that were responsible for the logging but neoliberal companies, following a strategy of imitative development.

Declarations of care for the environment and natural resources therefore became the trademark of the next wave of the Latin American drive for sovereignty. This wave was a reaction to several decades of neoliberal dependent development that, just like the previous phases, turned out to have deepened the underdevelopment. Not necessarily in literal terms – some of the countries in the region boasted a rising standard of living and consumption, with pockets of industrialization with the involvement of foreign capital (albeit less advanced and more volatile than had been the case with the earlier industrialization carried out under the auspices of the state as part of efforts to achieve independence). Catching up with the core countries was, however, out of the question; thus, the gap between the two grew. In Latin America, there still persisted large swathes of poverty, without access to basic services; social inequality increased, and even such basic problems as mass illiteracy had not yet been successfully tackled. With the concentration of capital and demographic processes, the number of famers without land increased. This resulted in mass migration, and urban centers struggled against the problems of chaotic expansion and the collapse of many vital functions. The incessant pressure on natural resources caused mass expulsions of population and led to the devastation of the environment and outbreaks of disease.

The new Latin American drive for sovereignty adopted various forms of organization. Armed struggle had not been abandoned – albeit now, conducted in a less bloody way, relying instead on the mass media – with the (neo-) Zapatista movement, which on 1 January 1994, took control and won informal autonomy in part of the Mexican state of Chiapas. Probably the best known was the MST, the Landless Workers’ Movement in Brazil, which demanded agrarian reforms oriented towards society and communal and egalitarian development of rural areas. The continent was swept by popular ferment; there were many more such initiatives, with movements for the protection of the environment prominent amongst them and capable of efficient mobilization. They often combined ecological postulates with demands for human rights and equality of the indigenous population, which had often been granted only nominal civic status.

Another form of these protests and one that became best known outside the region were left-wing political movements. They produced such popular leaders as Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil, Chávez in Venezuela, Morales in Bolivia, Rafael Correa in Ecuador, the Kirchner couple in Argentina, and so on. What these governments had in common were, in varying proportions, social transfers and attempts to emancipate the social masses. This was in keeping with the ideology of the left as well as pragmatic. First, it meant increased demand for various goods produced in the country, thus economic improvement and a greater independence from the swings of the global markets and whims of foreign importers. Second, the goal was to strengthen the legitimacy of the government, which was particularly important in the face of the habitual attempts to counteract any régime change, or even a weakening of the authorities in power, by the comprador bourgeoisie and the USA hegemon, although at that time such attempts tended to be the “soft” ones.

As mentioned earlier, the new wave of Latin American populism proclaimed concern for the environment and natural resources, triggered by the large-scale exploitation and destruction of nature in the region. This trend was combined with a rediscovery of the merits of indigenous culture and its cosmogony, with its reverence for “Pacha Mama” – Mother Earth. In some of the countries in the region, the new populism – besides focusing on social programs, an anti-USA stance, economic statism and a declarative concern for nature – set out to implement an anti-colonial project in the sphere of culture, through a regained emphasis on the value of native themes as opposed to Anglo-American and global culture.

The green movement was most prominent in Bolivia, where in 2010 on the initiative of President Morales, the Seven Principles of Mother Earth were adopted, encompassing key aspects of protection of environmental and biological life. In an international forum, Morales promoted his vision of the Declaration of the Rights of Mother Tierra, in analogy to the Declaration of Human Rights. In Bolivia, the principle of “buen vivir” became a national policy. It defined the “good life” not only in the context of industrial development and securing an adequate standard of living but also taking into account respect for the environment, the community, positive social relations, and non-material well-being.

Ruch robotników bez ziemi (Portugalski: Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Terra, MST), największy ruch społeczny w Brazylii i Ameryce Południowej, zrzeszający ponad 1,5 miliona osób. Źródło: wikicommons

***

In the countries of the region, such slogans were accompanied by practical solutions and legal regulation. Limits were set on logging in the Amazon rainforest and deforestation in general, some of the gigantic investment – mainly hydro-technical – was abandoned, and social participation, including local, and in particular Indian communities, gained acceptance in defining the direction of the environmental movement. It soon transpired, however, that this was an area in which the new governments found it especially difficult to keep their promises or abandon the neoliberal practices of the past. These countries faced a dilemma familiar to the underdeveloped economies of the periphery: what to export if you wanted to maintain economic equilibrium and you had no advanced goods with value added, how to finance your social programs and social progression. The answer was the same as before: natural resources, biological goods, and agricultural produce. Although today, the situation of some of these countries is much better than it used to be, thanks to, inter alia, industrial development and urbanization, at the same time popular aspirations have risen including expectations of the standard of living; populations have also increased. All this means that in these countries, still well behind the level of development that we are familiar with in the core capitalist countries, it is still the “natural economy” that is a significant source of income and which provides opportunities for the accumulation of capital. Without a doubt, almost all the countries of the region that have experienced the wave of left-wing populism can boast of the success of its social policies: providing social security to all, development of the educational system, a considerable reduction in the level of poverty, improvements in health, and so on. These improvements have not necessarily been paralleled by permanent changes in the protection of the environment.

Some of these countries based their new order on further, often more intense exploitation of non-renewable raw materials. The, not inconsiderable, difference to the previous situation consisted of changes in the ownership and distribution of profits. This was the case with the nationalization of the extraction industry and the processing of oil and natural gas in Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador. The exploitation of these resources indeed increased – but now the greater part of the income found its way into national budgets, providing funds for social programs (in Bolivia, for example, after the nationalization of the sector, the increase in the national income from the extraction of natural gas grew as much as eightfold). The example of Venezuela shows that it was very easy to fall into the classical trap of such one-sided development – when the price of oil fell on the global markets, the country suffered a deep crisis.

In turn, in some of the countries of the region, there developed industrialized agriculture and cattle breeding for export, especially in Argentina and Brazil, which – taking advantage of the favorable prices on the world markets – notched up considerable growth in that sector. This does, however, have many side effects. First of all, this resulted in continued deforestation for the purposes of grazing and growing land, as well as an increase in monoculture, employing vast amounts of artificial fertilizer and chemicals for the protection of plants, as well as transgenic organisms that stimulate the consumption of water and energy, and the related need to intervene drastically in the ecosystem. Moreover, much of the investment in the agricultural sector of these countries comes, unlike in the extraction industry and with raw materials, from foreign capital and world multinationals specializing in food and agriculture.

Since 2010, we can talk about a retreat from sustainable development policies in Latin America. This is especially visible in the larger countries of the region and those perceived as first-league players. In Brazil, where the social-democratic and statist policies have not only flourished in a great social success but also brought hopes of finally leaving behind the status of the periphery and joining the world’s incumbent new powers, we can indeed talk about a U-turn in green politics, especially in spheres related to the protection of the environment rather than broadly understood ecology. This is an important distinction, since relying on statistical indicators can be misleading. As an example, the construction of a huge river dam for the needs of an electric power station will bring about increased energy production from renewable sources (water energy accounts for 80 percent of the electrical energy use in Brazil) – but often what this means for the region is the destruction of the precious ecosystem and biodiversity, flooding thousands of hectares of the forest and causing water pollution, not to mention the social cost. For a number of years, Brazil has been revisiting the shelved, controversial projects for the construction of huge river dams. Agricultural monocultures servicing exports, mainly soy and beef, have sprung up. The problems of settlement pressure and illegal logging in the Amazonian rainforests have not yet been resolved. Since 2004, Brazil has succeeded in reducing the size of the rainforest destroyed annually by a factor of five, “from over 25 thousand km2 to only 5 thousand km2 in 2011 and has maintained logging at this level, much lower than during the previous three decades.”9 Nevertheless, pressure on the region continues, and in recent years, governments have increasingly succumbed to it. It has also transpired that the improvement in the Amazonian region has entailed more pressure and a worsening of the situation in other regions of the country – agricultural business, extraction, and logging have moved to locations less in the international spotlight.

In Ecuador, after just a few years, the extraction companies are no longer obliged to consult with local communities about their plans for new investment and its ecological impact. Even a country with such strong environmental protection credentials as Bolivia more and more frequently permits the exploitation of natural gas and other raw materials in zones previously protected from industrial activity. Marcin Rzepa, a researcher into the new left-wing populism in Latin America and its effects, concludes that “the eternal problem with innovation in Bolivia – essentially, that what is considered wealth is mineral resources, thus what is found rather than created – remains unsolved.”10

On a broader scale, this is confirmation of the thesis of Immanuel Wallerstein – one of the leading analysts of the system that has forced entire regions into permanent periphery – who concluded out that “historical capitalism is in fact in crisis precisely because it cannot find reasonable solutions to its current dilemmas, of which the inability to contain ecological destruction is a major one.”11 Wallerstein points out that the core countries of the capitalist system shift the side effects of environmental destruction on to peripheral countries, where the élites shift them to the masses, which have no means of escape from the situation, stuck at the end-of-the-line, the rubbish tip of this system of production.

***

In his now classic book Open Veins of Latin America, a sui generis manifesto against perennial periphery status, Eduardo Galeano accused the liberal élites of the region of being “ideologists of impotence,” incapable of the courageous deed of shaking off the mental and material manacles that keep the countries oppressed, poor, and backward. The events of the last 20 years show that the new populist leaders and movements in the regions have to an extent managed to get away from that kind of mentality. Much has been achieved in terms of social progress and in various aspects of public life, including access to education and civic participation in decision-making processes. As regards the development of the countries on the principles of “natural economy,” exploiting resources for export – the problem, although understood, persists. The periphery remains the periphery.

It is no good perceiving the issue in simplistic and moralist terms. Such an attitude to natural resources has been conditioned structurally and it goes back to the past and is intrinsically linked to the world power structure. Pressure on the ecosystem in the peripheral countries does not stem from ignorance; it is, rather, a consequence of the iron rules imposed on the exploited regions by the terms of global trade imposed by the superpowers.

Natural resources in their unprocessed form are often one of the few assets of these countries that can provide a quick financial fix without large local investment. They are both the curse and the blessing of thus endowed countries and regions, petrifying their development.

One must be careful in drawing analogies between regions distant from each other geographically and culturally, but it is worthwhile considering what Poland and post-communist countries have in common with Latin America. We share a similar past: a long enduring feudal system, with all its consequences. We share a similar place on the geo-economic map of the world. If the Polish reality is sometimes better than that in some of the Latin American countries, this is by no means due to our civilizational development and membership of the West. This may prove unpopular, but let us consider the half a century in which Central Europe lived through real socialism as a period in which efforts were made to overcome the peripheral status of this region. Although that period cannot be defended on the grounds of ethics or civic liberties, it would be hasty to disregard its efforts in other directions. The problem there was not necessarily isolation from the capitalist economy. Perhaps, as the example of Latin America shows, this was a salvation of sorts that allowed them to achieve in protected conditions a partial development of industry, urbanization, and egalitarian across-the-board public services instead of perpetuating a state of underdevelopment in the conditions of an unequal trade exchange with the West and functioning as its agricultural and raw material hinterland. Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria embarked on their adventure with communism as largely backward countries, with post-feudal economies. Half a century later, they entered capitalism with large cities, developed infrastructure, an educated society, heavy industry, and a national health service. Of course, they were still far behind England, Holland, or the USA – but then, they had been considerably behind these countries also in 1939. In comparison, the countries of Latin America, after a few decades of dependent development, in 1989, or even a decade later, still had dire poverty, illiteracy, and a lack of basic infrastructure beyond some metropolitan areas. This happened although nobody had isolated these countries from the West – as the Eastern bloc countries had been – on the contrary, they were involved in numerous relations with the counties of the capitalist core. The greatest failing of real socialism was, then, not isolation behind the Iron Curtain – as the naïve liberal narrative has it. The crux of the problem was the authoritarian, exclusive character of these régimes, which did not permit a process of actual political and civic emancipation of the social masses, gaining their support for at least a partial overcoming of the consequences of backwardness and peripheralization. To paraphrase Lenin, the problem of real socialism was electrification without the rule of the Soviets – popular support, commanding instead merely the authority of the alienated, privileged, new ruling class of Party apparatchiks.

To view the countries of Central and Eastern Europe as equivalent to the Latin American periphery would enable us, whilst registering regional differences, to notice certain crucial characteristics of the phenomena taking place. One must of course include the proviso that in Latin America, the rebellion of the periphery was expressed in stylistics that were more often left-wing that right-wing, since the local hegemon – the USA – worshipped capitalism, and the comprador elites and pro-American juntas belonged most often to the liberal right. In Poland, in contrast, the clichéd left-wing nature of real socialism as well as the region’s isolation from the capitalist West with its much-coveted standard of living and lifestyle resulted in a quite different orientation of sympathies. Today, the Central European initiatives that highlight sovereignty are usually right-wing.

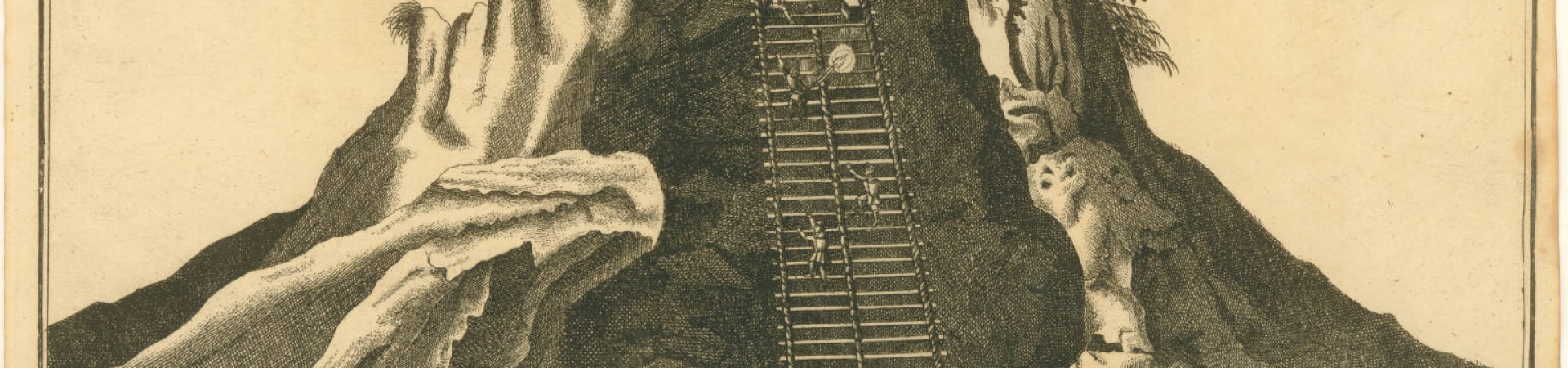

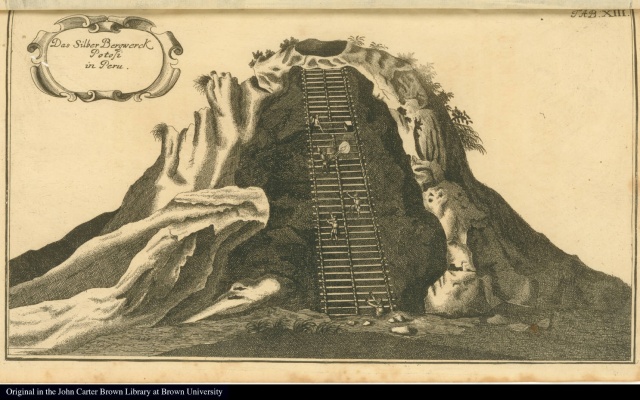

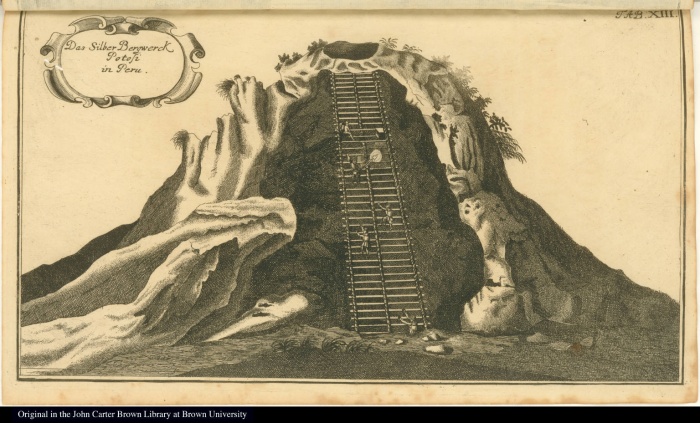

Franz Ernst Brückmann, Kopalnia serbra w Potosí w Peru (ob. Boliwia), grafika, 1727. ©John Carter Brown Library, Box 1894, Brown University, Providence, R.I. 02912

This should not stop us from seeing the structural dimension of the phenomenon. The rebellion of the periphery is often blind to the slogans it chooses to follow but this does not mean that it cannot recognize its peripheral position and desire to overcome it. The structural conditioning of the predicament of both regions is also similar – they were both long ago brought to the role of supplier of cheap agricultural produce and cheap labor. Their development potential has been curtailed, with little room for maneuver, and although it may seem morally valid to judge such countries by standards derived from the countries of the capitalist core, this is not a valid intellectual pursuit. If the countries in our region are not as immaculate ecologically as the countries of the West – since to a large extent they rely on coal and natural gas, exploit nature, use outmoded technologies, and are reluctant to establish protected zones – this is not necessarily because their élites are dim and backward or lack environmental awareness (although such circles also exist, of course). This happens because they are taking part in an unequal game – often a zero-sum game. A game, in which they are the periphery and not the core.

None of this means that Poland and the region should acquiesce in the role of the perennial object of exploitation (and self-exploitation), uncritically accepting the backward reality of the periphery, complete with its social and ecological consequences. It does mean that it makes sense to realize just how many of these aspects of reality are due to structural conditioning – and cannot be overcome through uncritical admiration of the West but, instead, through a laborious effort to alter the power game at least to some extent. The example of Latin American countries demonstrates that it is possible – if difficult, and the real processes and phenomena do not always follow the awareness and desires.

Translated from the Polish by Anda MacBride

BIO

Remigiusz Okraska is chief editor of the Nowy Obywatel (New Citizen) quarterly, founder of the Lewicowo.pl website, author of over 500 magazine essays, editor, initiator, and author of various afterwords for re-editions of classic Polish political-philosophy texts, e.g., by Edward Abramowski, Romuald Mielczarski, Ludwik Krzywicki, Maria Dąbrowska, Andrzej Strug, Jan Wolski, Jan Gwalbert Pawlikowski, and Franciszek Stefczyk.

* Cover photo: Franz Ernst Brückmann, The silver mine Potosí in Peru, engraving, 1727 ©John Carter Brown Library, Box 1894, Brown University, Providence, R.I. 02912

[1] Wojciech Giełżyński, Rewolucja w imię Augusta Sandino, Warsaw 1979, p. 94.

[2] Oskar Lange, Dlaczego kapitalizm nie potrafi rozwiązać problemu krajów gospodarczo zacofanych, in: idem, Dzieła, vol. 1 – Kapitalizm, Warsaw 1973, p. 740.

[3] Ibid, p. 744.

[4] See Fernando H. Cardoso, Enzo Faletto, Dependency and Development in Latin America, University of California Press, 1979.

[5] Tadeusz Łepkowski, Simón Bolivar. Rozważania o losach i dziele rewolucjonisty, unpubl. lecture, quoted after: Marcin Kula, Narodowe i rewolucyjne, Londyn – Warsaw 1991, p. 317.

[6] History Will Absolve Me, speech made by F. Castro in 1953, publ. by Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, La Habana, Cuba 1975; trans. Pedro Álvarez Tabío and Andrew Paul Booth; https://www.marxists.org/history/cuba/archive/castro/1953/10/16.htm [accessed: 29 January 2018]

[7] Andrzej Stawar, Zachód w Polsce, “Dźwignia” no. 4, July 1927.

[8] Marcin Kula, Boliwia 1952: Rewolucja narodowa, in: Zamachy stanu, przewroty, rewolucje. Ameryka Łacińska w XX w., collaboration, ed. by Tadeusz Łepkowski, Warsaw 1983, p. 146.

[9] Nie tylko o Amazonii, czyli ochrona środowiska w Brazylii – wywiad z Wojciechem Doroszewiczem, in: Brazylia, kraj przyszłości?, collaboration, ed. Janina Petelczyc, Marek Cichy, Warsaw 2016, p. 237.

[10] Marcin Rzepa, Przebudzenie obywatelskie, emancypacja Indian, nowa polityka. Problemy społeczne Boliwii, “Nowy Obywatel” no. 70, spring 2016.

[11] I. Wallerstein, 1997, Ecology and Capitalist Costs of Production: No Exit, 1997 http://web.boun.edu.tr/ali.saysel/ESc307/Wallerstein.pdf [accessed: 30 January 2018].