Some of the economic exchange policies that are being developed within the transactional FTA1 agenda, between the Colombian state and other countries, seem to be contradictory regarding the way in which natural resources are governed. The state applies a philosophy that emulates the concept of a private company by executing contracts with multinationals where natural resources are being negotiated in favor of the interests of private patrimonies. Due to this the Colombian oligarchy has inherited political and economic power, then this small group exercises control especially for corrupt and selfish purposes. Where profit and financial return are the priorities and the long-term social benefit of conserving natural resources is undermined. Colombian territory has the potential to develop clean energy, for instance in La Guajira at the northernmost tip of South America and situated on the Caribbean Sea, occupies most of the peninsula in the northeast region of the country and could support solar energy and wind power. However, the economic model that has been drawn relies on fossil energy and even worse government agencies are allowing fracking, which involves toxic substances that need to be injected directly into underground sources of drinking water. Although environmental accidents have caused a lot of damage to local communities, the Colombian oligarchy insists that fracking is not a hazardous technique.

For this reason, drastic soil modification for oil, coal, and gas exploitation has become an impracticable project that could change the nature and effectiveness of the soil. This is particularly true in areas of the peasant economy where the poverty caused by the state’s abandonment, and violence stemming from this epidemic historical practice, has increased the lack of advanced technologies, technical assistance, and exponentially raised the cost of agricultural inputs.

Miler Lagos, CHORRERAS, interwencja w przestrzeni miejskiej. Projekt site-specific zamówiony przez Biennale w Cuenca, Ekwador, 2016.

Hydrologists argue that water is the country’s main source of wealth because without this vital element the population could not survive. Nevertheless, the Colombian economy, which is backed up by some of the most influential and well-established multinational corporations such as those from the United States, continues to pursue the exploration of fossil energy and mineral deposits.

Among the paramount actions that are hidden and covered up in the public domain we can point out the collateral damage to the environment and the long-term implications for the domestic economy. Political campaigns use “Progress and Economic Growth” as a slogan, inferring that these types of agreements encourage technological advancement. However, water is one of the elements that are being highly sub-valued by the Colombian state. When land is transferred, or the state confers mining exploration benefits, these concessions operate in a doubly unbalanced direction, when shares of public companies are granted to multinationals, not only shares are sold, the domestic land becomes the property of an international corporation, which can dictate the market prices of the land. The state should regulate these transaction costs in relation to the income of their citizens, and prioritize their population’s basic needs, this does not happen however, and the result is to acquire these services through a private multinational company. Therefore, we obtain water, energy, and gas as just another of the products that are being imported.

This text highlights the practice of the contemporary art that is interested in the intersection between art and science, because this aptitude is aiming to contribute to this unbalanced political decision of hosting hostile and alien policies that will change our territory and therefore our people’s lives for good. That’s why in Colombia, we are fighting back as a society to rethink our hosting procedures.

Techno-scientific knowledge has been displaced to introduce populist discourses within the status quo of the population. Colombian policies are contradictory: instead of promoting development by applying common sense, politicians prefer to persuade people through their emotions, therefore irrelevant issues become more relevant for their campaigns. Of course, we know these kinds of practices are very common at election time, however in our country it has become the main philosophy, in this environment distractions and irrelevant subjects are the main discussion topics for senators and legislation seems to be drawn up without any logic.

For this reason this text will combine two projects providing, as an example, the research work of two different professionals, the first one is Miler Lagos an artist whose investigation and practice is rescuing ancient knowledge conveying uncanny terms of philosophy, science, and administrative functions that were carried out by pre-Colombian clans, for instance areas of knowledge that nowadays are trends of debate like astrophysics, geology, and agriculture were quite well understood by those communities. The second project comes from the contemporary study of physics, where I have interviewed Santiago Vargas, a Colombian astrophysicist, who specializes in the observation of the sun. Subsequently these two fields of knowledge will be combined to demonstrate the predominant dichotomy of the Colombian economic and political agenda and how we could hypothetically benefit as a society from applying bits of our indigenous heritage wisdom, or actualized theories of management, to grant Colombian inhabitants.

Cosmopolitan Forrest. Instalacja site-specific, rzeźby z gazet, Muzeum Sztuki, Kolumbijski Uniwersytet Narodowy.

Cosmopolitan Forrest. Instalacja site-specific, rzeźby z gazet, Muzeum Sztuki, Kolumbijski Uniwersytet Narodowy.

One of the Colombian artists that has reacted to these political and environmental issues is Miler Lagos whose artistic practice has explored the metaphorical possibilities of water as an element of multivalent expressions. One of his first approaches that has allowed him to comprehend how important water was for pre-Colombian tribes came about when he carved paper sheets in order to create sculptures that looked like wood logs. This was the beginning of an on-going investigation that led him to signify the historical function of printed-paper and its relationship to the culture in a global sense. For Western culture, the invention of printing and reproduction has been an important practice of historical documentation and knowledge preservation, nonetheless for pre-Colombian civilizations this knowledge was written within the nature; for them each plant and tree had its own meaning within the ecosystem. In order to accomplish this procedural objective, Miler has taken part in art residencies in various arts organizations around the globe. From these experiences, Miler Lagos has compiled distinctive constructions of meaning built from North American to Patagonian ancestral communities. For Miler, those locations where knowledge was passed down converged in some kind of spiritual exchange value; according to Miler for those tribes, in terms of well-being, a generous environment was the result of a celestial gift as bestowed by a superior being. He highlights how important water was for Mesoamerican communities; actually, their major developments and technological implementations were based on an accurate usage of water resources and its distribution both in symbolic and practical terms.

During his research and artistic practice Miler has come to some noteworthy conclusions: “Those ancestral cultures were constantly searching for water and being close to those sources of water was essential for them. For instance, the Muiscan civilization valued water mirrors more than gold. This mineral wasn’t mined to give it an exchange value, instead of erecting mines they preferred to improve their sites for settlement; in this order of ideas, for the Muiscas the significance of the land had a different value, not only was it understood as ritual locations where those communities gathered around. Paramos2 signified both a strategic place where they could communicate with their deities and grow as a united society; for instance, Bacatá3 was a religious center for the Muiscas, where the presence of water, wetlands, and the exuberant presence of animal species, made them understand how important the relationship between the micro and the macro cosmos is, that’s why they developed observations related to what, nowadays, we call the study of astrology. In the Bacatá area two mountains, Monserrate and Guadalupe, are located among other minor hills, which surround this geographical site. Somehow the Muiscas managed to recognize areas of solar radiation and from that discovery, they created an accurate agricultural calendar. Nowadays we still do not have clear acknowledgment of their measuring systems because when the Spanish arrived this civilization vanished from the Earth.” Miler Lagos’ artistic practice has created site-specific installations, kinetic artworks, and large-scale collages incorporating both the lost ideas of those pre-Colombian ancient civilizations and how they used materials, for this reason we can recognize matter derived from trees, and in that sense, the materiality correlated to water sources.

El Venado de Oro, widok wystawy, za zgodą Fabien Castanier Gallery, Bogota, Kolumbia.

El Venado de Oro, widok wystawy, za zgodą Fabien Castanier Gallery, Bogota, Kolumbia.

El Venado de Oro, widok wystawy, za zgodą Fabien Castanier Gallery, Bogota, Kolumbia.

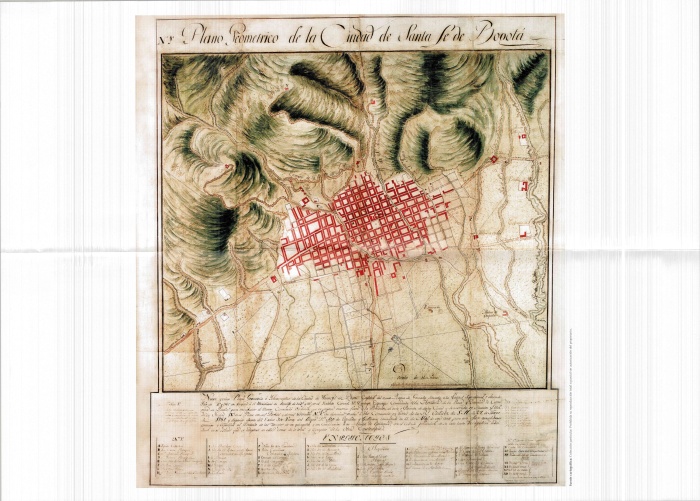

“During a particular visit to Ecuador, where Miler Lagos was doing research for the XIII Biennale of Cuenca, he was impressed by the city, where the rivers have an important presence. The waterway stretches from its origin in the proudly preserved National Park of ‘El Cajas’ to the heart of the city. The river is clear and along the way its purity can be appreciated, highlighting the respect and veneration that the habitants have towards it. This pristine quality urged Miler to reflect on his hometown of Bogotá, where the rivers that gave birth to Colombia’s capital city had a different reality. The city map was drawn in the foothills of the Guadalupe and Monserrate, between the two main rivers of San Francisco and San Agustín. The water that came down was the driving force for the mills that turned wheat into flour, enabling the industrialization of this process. More mills developed alongside the river, allowing for the mass production of paper, gunpowder, and finally electricity. Despite the ingenuity in harnessing its water sources, the inhabitants of the old Santafé of Bogota lacked a vision towards the future, not preserving the main arteries of these water sources, even though they would become decisive for the development and layout of today’s Bogotá. The basin of these rivers was named ‘The Hole of the Deer’ after an ancient legend that told of the existence of a golden Muiscan treasure. The mythical artefact resembled a deer whose horns were stolen by a fugitive from justice that hid in a cave in the Guadalupe Hill, where this treasure was placed during colonial times.”4

Miler Lagos established a relationship between the deers’ horns and the rivers and concluded that, for the Muiscas, water mirrors were instruments of communication between earth and space. Muiscas noticed how at some hours of the day the afternoon light has an orange spectrum and the savanna of Bogotá seemed covered by gold which is probably why they made the metaphorical association between the deer horns and rivers alongside Bogotá’s savanna.

El Venado de Oro, widok wystawy, za zgodą Fabien Castanier Gallery, Bogota, Kolumbia.

El Venado de Oro, widok wystawy, za zgodą Fabien Castanier Gallery, Bogota, Kolumbia.

El Venado de Oro, widok wystawy, za zgodą Fabien Castanier Gallery, Bogota, Kolumbia.

El Venado de Oro, widok wystawy, za zgodą Fabien Castanier Gallery, Bogota, Kolumbia.

El Venado de Oro, widok wystawy, za zgodą Fabien Castanier Gallery, Bogota, Kolumbia.

El Venado de Oro, widok wystawy, za zgodą Fabien Castanier Gallery, Bogota, Kolumbia.

One might say that the origins of the setbacks in terms of identity and development in South America was caused by colonization, specifically concerning the lost of pre-Colombian culture, whose devastation was caused in part by a vain misunderstanding of their mystical relationships and ideas of the sacred and wealth as they related to man and the landscape. This was summarized as an aesthetic of representation, rather than constructing a deepening investigation of the pre-Colombian environment. That wisdom has been misrepresented, as old-fashioned colonialist thinking ignored this understanding of the universe because it came from something they deemed hidden and dark, because pre-Colombian adoration of the stars influenced their decisions and made up their cosmogonies.

In order to familiarize our readers with the Colombian political dichotomies regarding the application of science, I have interviewed an astrophysicist, professor Santiago Vargas of The National Astronomical Observatory of Colombia at Santiago, who specializes in the study of the Sun. He will help us understand the importance of the ancient pre-Colombian knowledge that has been lost due to different periods of colonization and post-colonization.

Although astronomy is probably humanity’s oldest science, for some thinkers it is the mother of all sciences and has also accompanied us on our journey throughout the history of the planet Earth. From the dawn of civilization, astronomical knowledge was essential to answer fundamental questions about our environment, and about us. Astronomy is, in fact, one of the sciences that has more connections with other areas of knowledge: astrobiology, archaeoastronomy, astrochemistry, astrogeology, among others. These are just some of the fields where astronomy research is complemented by contributions from other scientific subjects.

Applying these concepts through an accurate model could provide us with innovative prototype methodologies, and subsequently this prospective scheme could be implemented within the Colombia economic agenda and hopefully improve educational and social thinking processes.

The molecular revolution5 has unveiled that we are connected beyond our philosophical conceptions as a human civilization, actually subatomic particles demonstrate that we are interconnected with complex universes and we aren't aware of this phenomenon, for instance. One of the fields of astronomy is directly related to the study of ancestral populations and their relationship with the cosmos is called archaeoastronomy. In Colombia, there are vestiges of the influence of astronomy in the life of the ancient settlers, for example in the Muisca culture.

Muiscas created numerical systems called Guarismos although this word has the same Latin root as algorithm, has a completely different meaning, there are many theories about this concept, but in this case, it is understood as a corresponding figure for each sign that is part of a number in a system, and that can be joined to others to express an amount, for this reason they used knot methods for counting. Using these mathematical methods, they were able to calculate the equinox and solstice for harvesting purposes.

Santiago Vargas claims that the study of the Sun and the Universe was important for ancient Mesoamerican civilizations and is it still highly imperative today. These ideas can become transcendent because they will change how we understand the geometry of the universe and the way our civilization has structured intellectual thinking. It is a fact that societies that have achieved a high degree of development have been structured from knowledge, and in particular, are based on a solid scientific culture. In Colombia, we are still a long way from achieving this, and there is no long-term scientific policy that ensures adequate support for scientific development and its application to solving local problems. There is, in general, little contact with science among citizens and there is no interest from the government addressing this deficiency.

The National Astronomical Observatory, founded in 1803, is the oldest observatory in the Americas and one of the first scientific institutions in Colombia. Currently, the observatory contributes to knowledge through the training of students in areas of astronomy and space science and leads research in various fields of astrophysics. A large number of initiatives are carried out with the community that brings science to children and young people and promotes the importance of scientific knowledge. Activities based on astronomical observation are performed with telescopes and presentations in the planetarium.

Educational models should promote critical thinking that is based on these same mechanisms, and that is essential for the training of students so that they can face diverse problems, not only in the field of sciences. There are several educational centers in Colombia that are incorporating among their activities, subjects related to astronomy, and generating new pedagogical dynamics so that students can participate in the design, creation, and development of projects. For example, at the Gimnasio Campestre school in Bogotá, where for several years they have been doing solar observations and have a record of solar activity based on data taken by students.

Science has a strong influence nowadays in economic development. In the field of astrophysics and space sciences, the relevance of satellites for the development of a country is increasing. Colombia has had a long delay in this sense, and it is necessary to encourage the start-up of a communications satellite and a terrestrial observation satellite. Both will bring great benefits by improving the country’s connectivity, as well as in the prevention of environmental risks, telemedicine, and agricultural planning in various regions among many other essential components for the growth of its economy and the improvement of its citizens’ quality of life.

The conditions for science in Colombia are quite regrettable. There is no scientific policy and there are very few resources devoted to science. The importance of science in government plans is minimal, and the situation to develop research is very difficult. There is a great lack of researchers and the scientific and technological gap in the country is increasing. It would require a huge state effort in order to correct this situation. One that would allow Colombia to achieve adequate scientific development that can help solve local problems and contribute to the global knowledge of humanity.

To conclude, the intention of this text was to present the current political environment of Colombia, which is close to presidential election time. Then the contradictory positions and false statements promising progress and technological development will be put forth by the conman of the minute. On the one hand, some traditional candidates are proposing the continuation of the war and feeding internal conflict with distorted media campaigns, on the other hand, there is a narrow sector of the population which takes the responsibilities regarding the implementation of accurate policies seriously that can allow us to integrate into a global civilization, and finally have the proper infrastructure both in education and works of modern engineering such as train networks, clean energies, and a sustainable agricultural economy. Then the combination of ancient knowledge, rescued by an artist and contemporary scientific research, will be a transversal intervention that can be carried out within art, science, and technological knowledge.

This cross-disciplinary and experimental methodology of research is an initiative that will disseminate challenging questions and from these kinds of projects our society can overcome its main struggles, not just producing new knowledge, but also new ways of establishing relationships among disciplines and this group of researchers and art practitioners will be opening those uncertain territories for the next generation of investigation platforms. Consequently, ongoing participation, knowledge sharing, and cross-disciplinary collaborations between artistic, scientific research, and practice will lay the groundwork on which new areas of speculation, critical institutional analysis, and alternative forms of documentation will arise.

BIO

John Angel Rodriguez graduated with a bachelor’s degree in visual arts from the District University Francisco Jose de Caldas Bogotá, in 2005 with an emphasis in New Media. He began his work as an artist while still studying fine arts, from 1999 to 2004, he participated in university salon halls, art collective exhibitions, open calls, and research grant projects. In 2002, he worked in the department of education at the National Museum of Colombia.

He has been working as an independent curator since 2004, Bogotá, and then he moved to London in 2007 to perform field research within London’s creative industries hub. In 2009, he was the guest curator for the Embassy of Colombia in London curating the exhibition EQUILIBRIO presented at the Southbank Centre. Parallel to his work as an independent curator, he worked at the Saatchi Gallery; one of the highlights of this period was the project Art Accelerating Art. In 2011, he graduated from the University of Westminster where he obtained his MA in Art & Media Practice.

His most recent awards include: The Fellowship for International Circulation IDARTES 2017 which allowed him to be a speaker at FACT, Liverpool, UK; The Colombian Ministry of Culture research project in Warsaw, Poland, presenting a lecture at Lokal_30 Gallery. In 2013, he received a grant from the Getty Foundation of Los Angeles, to attend the annual curatorial conference CIMAM 2013 "New Dynamics in Museums Curator, Artwork & Public Governance" which took place in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. He attended as the curator of the exhibition Digital Analogy: Pioneers of New Media. In March 2013, he was invited to perform curatorial research in New York, during this residence he gave a Hack TED talk at Eyebeam. The Fellowship for International Circulation from the Colombian Ministry of Culture; ISEA 2012, Machine Wilderness Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA.

* Coverphoto: El Venado de Oro, Views of the exhibition courtesy of the Fabien Castanier Gallery, Bogota, Colombia.

[1] A free-trade area is a region encompassing a trade bloc whose member countries have signed a free-trade agreement (FTA). Such agreements involve cooperation between at least two countries to reduce trade barriers – import quotas and tariffs – and to increase the trade of goods and services with each other.

[2] Páramo can refer to a variety of alpine tundra ecosystems. Some ecologists describe the páramo broadly as “all high, tropical, and mountain vegetation above the continuous timberline.” A narrower term classifies the páramo according to its regional placement in the northern Andes of South America and adjacent southern Central America. See. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/P%C3%A1ramo [last accessed 29.03.2018].

[3] Bacatá is the name given to the main settlement of the Muisca Confederation on the Bogotá savanna. It mostly refers to an area, rather than an individual village, although the name is also found in texts referring to the modern settlement of Funza, in the center of the savanna.

[4] Text by Julián Zalamea (translated from the Spanish) exhibition excerpt from El Venado de Oro (The Golden Deer), a solo show by Colombian artist Miler Lagos, who has created installations, drawings, and sculpture. The Fabien Castanier Gallery, Bogotá, Colombia, 2016.

[5] Molecular Aesthetics, ed. by Peter Weibel and Ljiljana Fruk, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA 2013.