Widok instalacji Nedko Solakowa "Życie (czerń i biel)" z 1998 r. Zdjęcie: (c) Nedko Solakow, 2007. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

If J.G. Ballard thought up a novel set in the Russian capital, one of the perfect places to situate his fertile imagination would be the Moscow International Business Centre, better known as simply “Moscow City.” Not because it distantly resembles a complex of tower blocks designed by the godlike Anthony Royal, the fictional architect from High-Rise (1975), but in the sense that it also has a dystopian potential equal to the places the British writer glorified in his books. “Moscow City” is a trap as well as a kind of asylum like the triangular wild area between highways in another of Ballard’s novels – Concrete Island (1974). Such places function as a modern Noah’s ark, conserving vanishing forms of life and society in a specific hibernation. Layers of materials, fashionable for some period and outmoded later, are quietly growing together; and elements of different ideological content stay mixed till somebody wakes them up.

1.

In the middle of the 1990s, Moscow mayor Yury Luzhkov started a development project in the northwest of the city in order to create a complex of skyscrapers. More than two dozen buildings, mostly skyscrapers, standing above the ramified underground structure of a huge shopping mall, a Metro station, and several parking levels. It was to host approximately 300,000 residents, hotels, the editorial offices of glossy magazines, and especially offices. Here, hundreds of businessmen and businesswomen produce national wealth in a non-stop rhythm of work. This area was expected to become the financial post-industrial pole of Russia and the post-Soviet region in general. Not a regular pace “downtown” growth, slowly step by step, but the expansive headquarters of a newborn dynamic and hungry class – Russian bureaucrat-capitalists.

These plans seemed to be perfect but were destined not to be completed that quickly. First, Russian companies were seriously damaged by the crisis of 1997–1998. As the prices went up rapidly and the ruble crashed disastrously, the entire development was frozen. During that time, they started to build only one skyscraper which was completed in 2001 and a common foundation for the whole complex. The construction of other skyscrapers was initiated only in the middle of the 2000s when a new national strategy of bolstering the economy with oil money was finally established. Although the financial crisis of 2007–2008 slowed down this process a bit, the story had an interesting twist. In time, the nearly completed “Moscow City” could be extended into the so-called “Big City” or “The New Center,” a project which was supposed to transform a large part of Moscow’s northwest (comparable in size to an old city center) into a luxury district with highly expensive real estate.

But misfortune descended upon “Moscow City” in 2009. The new president of Russia at that time, Dmitry Medvedev, decided to implement a quite similar project outside of Moscow, in a place called Skolkovo, which should have become a town of innovative industries, a Russian “Silicon Valley.” Run in a very Soviet style, this campaign for innovations accumulated most of the investments. Furthermore, the entire force of the state was focused on this goal, this new mega-project. In 2010, Yury Luzhkov, the main locomotive figure of the “Moscow City” project as well as a cunning political schemer, was displaced from his position by the president. It was so unpredictable that it shocked everyone, but very soon lots of Muscovites began urging the new city administration to close down all of “Luzhkov’s” construction sites, even to demolish some of the facilities and monuments that had already been built. And, of course, several critical voices were raised against such an expensive project as “Moscow City.” However, it continued to grow, new buildings appeared and even without many people working in them they symbolized the strength of the metropolis.

The next crisis started in 2014 when international sanctions were imposed after the Russian annexation of Crimea and the war in Eastern Ukraine. Obviously, this had a very negative influence on the real estate market, but it didn’t shut down this mega-project mostly because it had already gone too far for more than 20 years. Business newspapers have regularly written that it’s a bad time for the skyscraper owners and investors, they can hardly find any renters. Thousands of square meters of office space were abandoned. Also they found that, in terms of logistics and infrastructure, the area is really problematic and uncomfortable.

2.

Sure, they did try to transform – of course partly and temporarily – this complex into a site for contemporary art: one of the skyscraper’s lobbies became an exhibition hall for a short period, and in 2007 the then-uncompleted Federation Tower, Europe’s tallest building (actually there are two skyscrapers on a common stylobate), was a key venue for the main project of the 2nd Moscow Biennale. Ironically and symbolically, the main blockbuster artwork located in the high-rise was Nedko Solakov’s piece A Life (Black and White) (1998). Two painters simultaneously cover the walls with black and white paint moving around the room one after the other and thus destroying everything that the other artist has already done. For a while, the Bulgarian artist (and his performers) became a genius loci of “Moscow City” because the infinite creation of this place looked as absurdist as the artwork.

But as is a typical artistic approach, failed architecture as well as failed anything usually becomes a more interesting topic or object than a successful action. Mistakes or – even more – cosmic errors attract attention because of their experimental capacity and as a chance to explore a radically new situation.

One Russian artist almost literally fell in love with “Moscow City.” Victoria Marchenkova tries to articulate an intimate feeling of staying there in her video moscowcitythanks (2015). But all she can produce is a gaze through a window, from one skyscraper to another. “To shoot the video, I was searching for an ideal location, I was looking for a special kind of light,” says the artist, “And I do appreciate the tranquility of the skyscrapers. So high above the ground, so quiet! I always feel solemn there.” There was only the LED sign with an ad on the opposite skyscraper and a glass of wine to accompany her. “That is the only place in Moscow you can go to be on your own, and it’s where it pains your ears a bit in the elevator, when you are standing among the structures of glass and metal as if in a realm of abstractions,” adds Marchenkova, “I can easily understand why the head of Goldman Sachs went to his office in a private elevator. The higher you go, the clearer your mind is and the less you want to see any living soul besides yourself.”

The artist says that the magic is in the altitude, in the abundance of reflections on the glass interface of the high-rises, the pleasant atmosphere of weekdays full of city men babbling about startups while the sport cars roar. “I often hear from my architect friends that ‘Moscow City’ is cheap Chinese junk, all that stuff,” Marchenkova explains, “Most people look at the skyscrapers as if they are just glass boxes but none of them have even been inside.” However, it’s the only place in Moscow, the artist concludes, where she feels like an angel. Literally.

Klatka z filmu "moscowcitythanks" (2015), (c) Viktoria Marhenkova. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

3.

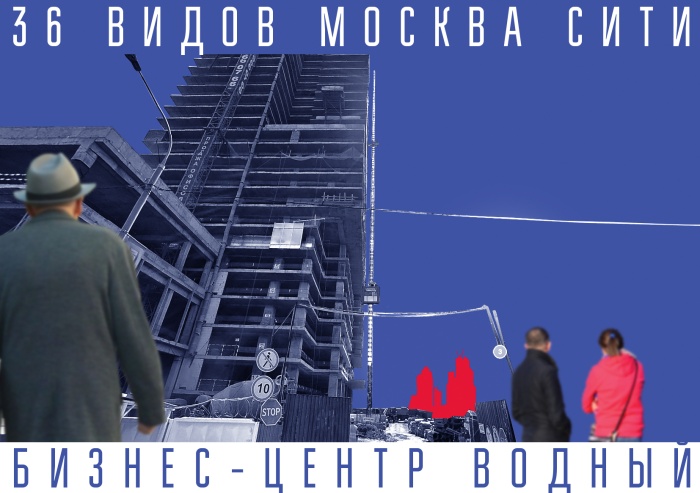

Visible from many areas, “Moscow City” reminds one of Mount Fuji, but an artificial and multi-peaked one. It is more appropriate to examine it in terms of an aesthetic phenomenon or object for contemplation rather than something functional. Another Russian artist, Sara Culmann, made this analogy visible in her project 36 Views of Moscow City (2015), an homage to the classical woodblock print series by Katsushika Hokusai, which was produced for the program “Expanding Space” conceived by the V-A-C foundation. The images represent different points of view from other business centers scattered all around Moscow, minor brothers and sisters of the giant skyscraper complex. Each of these pieces looks like a simple “landscape painting” from the post-internet era of urban environments (we can call them photoshoppings). Blurred human figures, grey buildings – and a red stain marking the city’s dominant point on a neutral blue basic layer.

In the video which plays a central role in the project, Culmann starts with a reference to the financial crisis of 2014–2015 and then shows how, according to her own statement, a “necropolis” of half-empty high-rises turned into a sacred place “performed the same analogous role the ziggurats, pyramids and kurgans did for the flatland folks.” It’s not just a grave for the hopes and desires of the previous generation of the business class but rather a temple which serves the needs of a certain dark cult: of Siberian oil, hidden offshore money, and war plans.

“The system formed by the master skyscraper and the remaining vassal-buildings presents itself as a scheme in which the center is the zero-point, surrounded by peripheral meanings,” explains Culmann. This metaphysical void is what “Moscow City” presents.

But this void can be reversed inside out. There is another dystopian zone in the city – Terekhovo a village which became part of Moscow in 1961 but wasn’t rebuilt; its architecture and life are still the same. Surrounded by highways and residential complexes built over the last 50 years, the village reminds one of the forgotten area from Ballard's Concrete Island. It is made up of 24 old townhouses and approximately 80 inhabitants. Terekhovo is just 5 kilometers away from “Moscow City” and they have an amazing view there. This picture taken by the artist Alexey Shulgin in the village speaks for itself: you see no Moscow, only empty land, a distant forest, and the peaks of the high-rises under a cloudy sky.

Obraz z serii "36 widoków Moscow City", Sara Culmann, 2015. Photo:(c) Sara Culmann. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Obraz z serii "36 widoków Moscow City", Sara Culmann, 2015. Photo:(c) Sara Culmann. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Obraz z serii "36 widoków Moscow City", Sara Culmann, 2015. Photo:(c) Sara Culmann. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Obraz z serii "36 widoków Moscow City", Sara Culmann, 2015. Photo:(c) Sara Culmann. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Obraz z serii "36 widoków Moscow City", Sara Culmann, 2015. Photo:(c) Sara Culmann. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Obraz z serii "36 widoków Moscow City", Sara Culmann, 2015. Photo:(c) Sara Culmann. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

4.

In a way, this huge, partly dysfunctional complex – the embodiment of inconsistent government procurement – repeats the fate of the VDNKh (the colossal Soviet permanent expo) and unfinished – better to say, still “unstarted” – projects like the Federal Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow. For instance, in the 1990s VDNKh was transformed into one big market place and now the city government is trying to erase all that remains of this decade, unpopular for political reasons. They expelled the majority of vendors and restored Stalinist architecture while at the same time demolishing the buildings of the 1960–1980s. And they wanted to make it an expo again as well as a museum complex. But this didn’t work: VDNKh has turned into an inhospitable place with crowds of people aimlessly roaming around.

But concerning “Moscow City,” it can definitely be transformed into a museum, a vertical gallery of the 1990s and 2000s in Russia. The skyscrapers grew up feeding the life-force of the country and that’s why it has the possibility, right, and duty to represent it. There are many more materials than just glass, concrete, plastic, and metal. Every part of these buildings is made from our emotions, phobias, and joy. Just as during previous centuries, the European bourgeoisie took back the power and turned king’s palaces into museums (like they did in the Louvre, Versailles or the Berlin Palace) and as the Bolsheviks did after 1917 (the Hermitage), a future generation in Russia may reclaim “Moscow City.”

But it could become anything besides a museum. The ways “Moscow City” could develop are that numerous exactly because this construction has turned out to be a kind of historical mistake. And as the first error produces a series of subsequent errors and deforms the initial plan, the potential functionality of the complex acquires characteristics nobody had expected. Anything can happen, as contemporary philosophy never tires of repeating.

BIO

Sergey Guskov, born in 1983, and based in Moscow is a journalist, art critic, and curator. Since 2013 he has been the editor of the art section at the independent Russian website www.colta.ru, contributing editor at DI magazine (Moscow, since 2017), correspondent at the magazine Metropolis M (Utrecht, from 2014). In 2011–2012 Guskov was the editor-in-chief of the website www.aroundart.ru (now www.aroundart.org). In 2016, he was the editor of the art section at the magazine Interview Russia. In addition, he has contributed to ArtReview Asia (magazine, Beijing), Art21 (website, New York), Ran Dian (magazine, Shanghai), Leap (magazine, Beijing), Prōtocollum (magazine, Berlin), ArtLeaks (website), The Art Newspaper Russia (Moscow), Artguide (website, Moscow), Moscow Art Magazine, Artchronika (magazine, Moscow), Iskusstvo (magazine, Moscow), Winzavod Art Review (newspaper, Moscow), Kommersant Weekend (magazine, Moscow), Ocula (website, Hong Kong) and other publications. Guskov has participated in a working group for reforming the Moscow Biennale (2011) and in an interdisciplinary collective the Supostat Agency (2011–2012).

* Cover photo: Moscow City, Alexei Szulgin, 2016. Courtesy of artist.