Senghor is universally recognized as the co-creator of Négritude, the theory of the black man’s specific way and right of way in the world. Despite the seeming obsolescence of Négritude, rereading Léopold Senghor, re-describing him from newer perspectives can still offer fresh possibilities for understanding Africa’s current fate. Not just in terms of development but also in cultural politics and art. Understanding the cultural origin of Africa’s predicament will create the urgent need for a radical change not only in Africa’s fundamental self-description but also in its current cultural politics.

Elizabeth Harney’s book In Senghor’s Shadow: Art, politics and the avant-garde in Senegal, [1] is perhaps so far the most careful and generous documentation of the rich and colorful cultural and artistic life in Senegal during and after Senghor’s reign. In this book Dakar, Senegal’s capital, comes across not only as a privileged lieu de memoire of Africanism, Pan-Africanism and African art but above all, as Négritude’s last fortress. Senghor’s thick shadow does not just envelop the city but dictates and orients the pace and rhythms of its ebullient cultural and artistic life. Harney is largely right because Dakar, though capital of one of the poorest African nations, has, because of Senghor’s famous shadow, managed to become one of the richest cultural capitals of West Africa as well as one of the better known cultural temples of Pan-Africa. Having harvested and benefited from the riches of Senghor’s vast artistic and intellectual endeavors, Dakar has worked itself into a veritable laboratory of Africanism, Pan-Africanism and modern African art. In 1966, it hosted the first Pan-African art and culture festival where a Pan-negro Négritude was curated and shown before a worldwide audience. Its skyline is adorned with many historical monuments, the most spectacular being the African Renaissance Monument. Today Dakar is host to Dak’Art, perhaps Africa’s most ambitious global art biennale. Indeed Dak’Art is the global celebration of an African art as inspired and supervised by Senghor’s shadow. With Dak’Art and other events like the Dakar rally, one can see that Dakar, though center of a certain cultural Africanity, is also a very eager candidate to the cultural globalization of Africa. The fortunes of Darkar especially Dak’Art no doubt derive directly from Senghor and his many shadows. But what makes Senghor and his posthumous shadow still so influential and inspirational?

Pomnik Afrykańskiego Odrodzenia (2006-2010), Dakar. Zdjęcie: wikicommons.

Senghor is universally recognized as the co-creator of Négritude, the theory of the black man’s specific way and right of way in the world. As the originator of Négritude, Senghor carries the burden of not only being one of the grand theoreticians of the doctrine of Africanism but also of having created what can be called the Afrophiliac impulse in modern African thoughts and action. The Afrophiliac impulse can be described as a cultural-nationalistic obsession with the uniqueness of Africanness which have resulted in such cultural and political doctrines as: the African Path to development, the African renaissance, African solutions to problems etc. The moment Africa’s self-definition was inscribed in Négritudian terms, i.e., the moment Africa was said to possess a unique black soul, a particular African way different from the world’s modern way, it became logical for Africa to see itself as requiring a different way of living, thinking, feeling and achieving progress. Thus what started as a psychological need for self-assertion became the constraining logic of a compulsive differentiation and exemption from what the leading cultures and peoples of the world knew, and did, to lift themselves up and improve their material situation. Today many think that a major reason why Africa remains poor is because of the foundational choice it made to pursue an African way of thinking and acting. As this choice was dictated by the philosophy of Africanism, Senghor along with other masterminds of the African Way cannot be absolved from responsibility for Africa’s current predicament. Thus despite the seeming obsolescence of Négritude, rereading Senghor, re-describing him from newer perspectives can still offer fresh possibilities for understanding Africa’s current fate not just in terms of development but also in cultural politics and art. Understanding the cultural origin of Africa’s predicament will create the urgent need for a radical change not only in Africa’s fundamental self-description but also in its current cultural politics.

One way to elucidate the Senghorian genealogy of Africa’s prevailing cultural politics in a way that will aid the change in the cultural conversation and art of Africa is to go back to the place culture occupied in Senghor’s thought and politics especially in the early nationalist days. Right from his earliest writings, Senghor strongly believed in what he called “the primacy of culture” not only in the regeneration of the African but also for his endogenous, Africa-driven development. To demonstrate this belief in the primacy of the cultural, Senghor is said to have devoted 25% of the national budget of Senegal to cultural matters. The belief then was that unless Africa could prove to itself and the world the validity and authenticity of its civilization, its diverse cultural heritages, it would neither be able to recover its wounded dignity nor find the self-confidence and native ground for a proper endogenous development. Thus the Senghorians were convinced that if they did not first get the cultural question settled, nothing else could be settled in Africa. Under the spell of Négritude, culture was the basis and the end goal of the conversation of Africa and Africa was seemingly never done with talking to itself in this manner. Indeed, it seems to have derived its greatest sense of power from this endless narcissistic self-affection. But culture in the Négritudian sense was essentially a fixed ancestral property that Africans, by virtue of some bio-cultural inheritance, were said to possess once and for all; it was the ensemble of Africa’s way of life which colonial Europe had badmouthed as primitivism and savagery. The task before the generation was to prove that it was as valid a form of life as any other world culture. The result of this massive preoccupation with culture and the mobilization of cultural resources towards the restoration of the damaged dignity of the black man was that cultural, nationalist Africa expended huge resources and energy into wars of cultural recognition and self-rehabilitation. Senghor’s Dakar naturally became the launch pad of African culturalism, the cultural-artistic laboratory of Africanism, the intellectual receptacle for many experiments and adventures in the Africanization of knowledge. As has already been mentioned it hosted the first Pan-African art festival; today it is home to a militantly Afrocentric knowledge production factory, namely, Codersira. [2]

Were Senghor to be just this one-dimensional Négritudian monolith; were his works to be reduced to Africanism, Pan-Africamism and cultural nationalism and Dak’Art, his place in the history of Africa’s modern self/world narrative would still be adequately assured but it would be boring and of little interest to the future of Africa. Fortunately Senghor, though often pigeon-holed in Négritude/Afrophilia, is a thinker so flexible and manifold that perhaps his most far-reaching contributions can be said to lie beyond Négritude and Africanism. The truth of the matter is that Senghor spoke almost simultaneously out of both sides of his mouth: he spoke Négritude but also that which exceeds and annuls Négritude, namely, modernity, universality. He embodied both the politics of difference and the politics of integration into universal civilization. However, the anti-colonialistic, nationalist generation had ears only for the Senghor who spoke Négritude. Today’s generation that no longer has ears for Négritude has rediscovered and paid greater attention to the second Senghor. In this study, I want to further foreground this second Senghor, indeed making it more performative, in the light of what is called Post-Africanism. Post-Africanism as the name implies, is about a radical change in the way we think and speak about Africa, the modern African self and its place in the world. It contends that the old cultural politics of Négritudian Africanism is not only obsolete but is actually what is seriously getting in the way of Africa’s normal growth and development. Post-Africanism analyzes the comparative disadvantages of still thinking and talking about Africa the way the anti-colonial pioneers did when they sought to salvage Africa and the black race from cultural disqualification by colonial Europe. A new cultural politics, Post-Africanism is a radical departure from the thought patterns and vocabulary of Africanism. Since in Africanism, Africa was only talking to itself, conversing with itself and perpetually admiring itself, Post-Africanism is about Africa discontinuing its ontological monologue and going out of itself and starting a new conversation with global modernity. It is a matter of what to do with Africa no longer seen as a Négritude, i.e., a world apart, but as an integral part of the global world, a joint heir to the fast globalizing modernity heritage of mankind. Now in a situation where Négritudian Africanism still largely shapes cultural politics and the arts in Africa and Senghor is still largely perceived to be fully embedded in Africanism, I want to show, with the aid of a Post-African theory, that it is possible to undo the stranglehold of Africanism on Africa’s cultural and art world. One way to do this is to Post-Africanize Senghor’s thoughts and art; another is to use the Post-Africanized Senghor to identify and then slay Négritude’s many unexamined or undetected cultural-nationalistic shadows still hovering over Dark’Art and lurking around the African art world as a whole. The idea is that Senghor read beyond Négritude and redeemed from Afrophilia can indeed not only shine a new light on the contemporary art of Africa but point the way to both a new art and a new future for the black continent. In the sections that follow, I want to carry out a Post-African analysis of Senghor’s thoughts and art; then I will try to make a case for a Post-African Dak’Art, i.e., a Post-Senghorian theory of African art and culture.

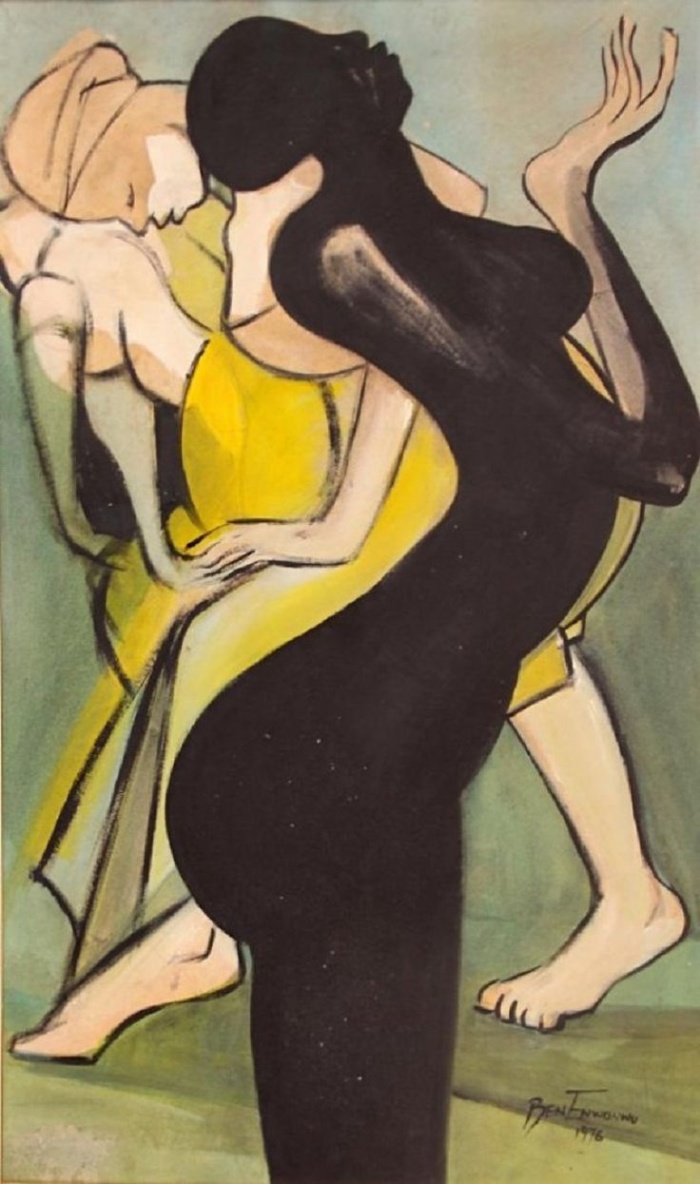

Ben Enwonwu, Négritude, 1957. Akryl i akwarele na kartonie, 120 x 75 cm. Dzięki uprzejmości Fundacji Bena Enwonwu.

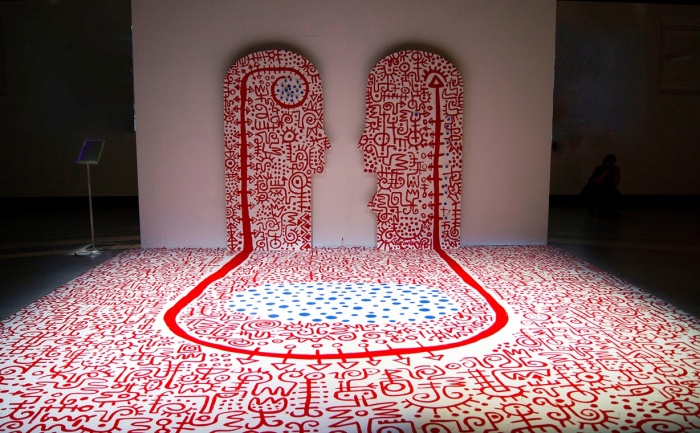

Victor Ekpuk, TOTEM Stan istnienia, widok instalacji z Dak'Art 2014. Dzięku uprzejmości artysty.

The Post-African Senghor

As already stated, the richness of Senghor lies in the fact that he not only spoke out of both sides of his mouth, his artistic creations derived from and fed the plural forms and shapes of his humanistic ideals. He created Négritude because he strongly believed that African civilization, the outcome of a set of specific responses to the constraints of a particular environment, was necessarily different from say European civilization. Consequently, African culture, values and norms can be only deferent from, rather than inferior to, European culture and values. Négritude was accordingly a re-affirmation of pride in Africanity, a love of cultural roots and a readiness to defend it but at the same time, a suspiciousness of colonial culture that mocked and denigrated all forms of Africanness. ‘Femme noire’ [3] is the emblematic poem that embodies this prideful, self-satisfying re-affirmation of the intrinsic beauty, coherence and validity of negro-African civilization. However, the same Négritude griot who sang femme noire [black woman] went on almost about the same time to intone clearly pro-colonial/pro-Europe songs in poems like ‘Neige sur Paris’ [4], ‘Prierre de Paix.’ [5] In the former, he began by deploring some of the cultural reversal works done by colonialism [e.g. turning his native princes into colonial house boys and sacred forests into highways]. But he quickly remembers that even such destructive works were necessary to prepare the way for the coming of the light of the Gospel and scientific modernity into Africa. In the other, he asks God to forgive Europe for its destruction and to bless her for the good works she accomplished in Africa. He singled out France for special divine blessings by asking God to place her at the right hand of His kingdom. With this, we can appreciate the ominous dualism and complexity of Senghor’s thought and art. As the poet of ‘femme noire’, ‘masque noire’, Senghor triggered the back-to-the-roots cultural and artistic revolution and as such, he can be said to be responsible for the more or less unconscious re-primitivization of Africa, the subversion of cultural change, the blockage of the transition to modernity. At the same time, as the most eloquent pro-Europe thinker and artistic trans-valuator of colonialism, Senghor represents the deepest intimation and performance of what it takes for Africa to become a fully modern continent. Unless we reckon sufficiently with Senghor the Janus [the two faced monster] we will not be able to separate the two distinctly antithetical forces he incarnated during Africa’s acculturation ordeal. I first hinted at this Janus-like Senghor when I discovered through a study of his art and thoughts that though he spoke Négritude, he thought and acted Eurocentric. [6] I then tried to analyze the implications of this smart double game strategy in his neo-colonial dealings with France. Here I want to suggest that this Senghor who deliberately suppressed Négritude, [suspending it in a purely aesthetic-cultural museum or reducing it to merely outward rhetorical symbols and displays for the purpose of artistic prestige and fame], when the time came for serious work especially building the institutional infrastructure of his nation, the modernization of the polity and economy, is that Senghor who holds on to the deepest intimation of what I call Post-Africanity, i.e., the logic of the necessity to considerably de-Africanize our thinking and feeling so as to facilitate the transition to a modern way, to a more universal consciousness. In what specific way can Senghor become a Post-African advocate? How can we tweak his thought and art so that they chime more with the needs of this Post-African time?

But first let me say more about Post-Africanism. I first spoke of it as a new cultural politics for Africa. I can now elaborate on this. Post-Africanity is the consciousness that comes after the troubling empirical realization that the grand theories of Africanness, Négritude, Afrocentrism etc. put forward by the pioneers including Senghor, have, when translated into models of reality, i.e., into cultural, political and economic choices, only so far succeeded in keeping Africa increasingly small, poor, violent and inhuman. The Post-African awareness drives an urgent need for a conscious redemption from all forms of Afrophilia, i.e., all forms of narcissistic narratives and paranoid world interpretation that have denied African thoughts and actions competitive advantage in the globalizing post-imperial logic of today’s world. Post-Africanism is an attempt to understand why Africanism does not work or works only to generate perversity, disorder, poverty and underdevelopment. Before I move on to how Senghor can be Post-Africanized, I shall briefly duel on Post-Africanism as a critique of Africanism, a new understanding of its pitfalls and attempts to overcome them.

The central idea of Post-Africanism is that as humans living in the modern era, we are not our Africanity, i.e., we are not and cannot, be limited to such a restrictive, narrow and constraining identity; as co-inhabitants of the global era, we are infinitely more than what all the self-narratives of Africanness have attempted to reduce us to. We are not bound by, nor limited to, the AU authoried narratives of Africanness such as African identity, African culture, the African path to development, African solutions to problems, the African Renaissance etc. We are obviously more, different and better than all these identity boxes. Indeed to have allowed our imaginations and brains to be caged for so long in these exclusivist and paranoid tales is no doubt the greatest harm we have done to our bio-human potential to be infinitely more, better and stronger. Therefore, in Post-Africanism, we quickly disidentify from all those limiting and impairing neo-tribalist self-narratives; rather we identify fully with not only the highest thoughts, best values and skills of globalized modernity, but also with the infinite possibilities available to man in this burgeoning quantum universe. Accordingly, in Post-Africanism, we take a step back from all the inherited theories and narratives of Africanity [in which we have all hitherto moved and had our being] so that through supra-African reflective awareness, we can understand the Afrophiliac thought patterns that are running our self-understanding, world interpretations, actions, and artistic creations. The aim is to get a clearer picture as to what the conscious and unconscious patterns of Africanism are that lead us more and more to the wrong outcomes; how these patterns were constructed and what we need to do to think, feel, act and create differently.

The Genealogy of Afrophilia

Africanism as an ideology exists as a combination of a nativistic narcissism and anti-colonial paranoia. It was created and not found. That is, it did not originate as a self-generated idea or image of Africa - it was not how Africa wanted to be spoken about - it was created in reaction to what Europe said about Africa and Africans. Africanism whether as Négritude, African personality or Afrocentricism, exists as a counter-discourse to colonial discourse. Sartre famously captured its reactive genealogy this way: it was a matter of the pioneer elite picking up the word black/African that had been hurled at them as a stone and using it as the corner stone of their identity construction and self-assertion. [7] But it was an indignant and vindictive self-assertion whose hidden driving emotions were shame and fear. The first acculturated elite, suddenly began to see themselves through the colonial eye of Europe, discovered that they were naked, had no history; no civilization. Having internalized the Europe gaze on them, they felt secretly ashamed. The shame plus the dread of admitting to themselves that they were ashamed drove them to over-compensatory idealization and celebration of Africa resulting in a defensive, over-protected image of Africa, an Africa extracted from any lived reality and floating in some aesthetic-poetic void. Then the fear of being thought inferior by the white man aggravated the indignant self-assertion resulting in a paranoid sense of self as always in a state of comparison. The strong assertion of a differentiated or separatist self-consciousness was the reverse side of an impotent vengeance against those whose apparition had installed shame and fear in us. So Africanism being a romantic self-affirmation/celebration, was at the same time a perpetual accusation; any affirmation was ipso facto an accusation. Both affirmation and accusation were directed against the bad white man who had so badmouthed Africa and Africans. In other words, in Africanism, we affirm and celebrate ourselves in order to accuse; we accuse in order to be. The imagination of Africa got caged in this affirmation-accusation pathos like in an iron box and the limits of that box were mistaken for the limits of Africa and the world.

Post-Africanism is a summons to liberate the African from the prison house of Africanism. To do so we must start by re-processing the twin primitive anti-colonial emotions, shame and fear, that drove the construction of Africanism. With the benefit of Post-African hindsight, we realize that those emotions were both unfounded and badly processed. Africa needn’t have felt any shame when the bad white man told him he had no history, no civilization, no morality. The only possible answer to such an accusation was: that was just how Africa was and it couldn’t have been otherwise since Africa had been isolated geographically for millennia, from the oxygen of contact with other cultures, such contacts being the driving force of change and evolution. The trans-Saharan trade route through which Africa would have hooked up with the Mediterranean world was later blocked by Islam which proved to be culturally, an even more untraversable desert than the Sahara. Fear of what the bad white man thought of us was highly exaggerated. The truth is that even in those colonial days, they really never cared about us; they cared about building up their world power. Africa was only a stop in their imperial drive to become masters of the whole earth. The first elite exaggerated Europe’s contempt for Africa and the impact of such contempt upon our sense of dignity and pride. The inferiority complex they contracted was mostly the outcome of their exaggerated fear of how low the white man rated them as opposed to the truth that the white man barely cared about them. However, though colonial shame and fear were largely unfounded, these negative emotions succeeded in driving Africa into a panicky, alarmist state of Afrophilia: a compensatory over-protectionist sensitivity to the image of Africa and the African resulting in a quarrelsome, paranoid attentiveness to any gesture, act or word considered a slight on Africa’s dignity and pride. It is a state in which we live our imagined Africanness as both a fixed idea and a settled principle of thought, action and reaction. In it we claim to have discovered how Africa wants to be spoken about, what choices, policies and solutions best suit its specific essence and character and personality. That is how we came to talk of an African path to development, and African solutions to problems.

However, in Afrophilia what we love about Africa are precisely those things, those traits including traditions and worldviews that can no longer aid our survival and growth in this ever-changing modern world environment into which Africa, since colonialism, finds itself thrown. Under the anti-colonialist spell of cultural nationalism, theories like Négritude blackmailed Africa to return to those very roots ancestral traditions, archaic beliefs, and customs- that had kept our ancestors stagnated and thus became colonizable in the first place. But in returning to these no longer adaptive roots, Africa had deprived itself of the world transforming power of creative destruction, evolutionary selection. For in the state of Afrophilia, what was fated to disappear or be destroyed has been kept safe; what was to change has remained unchanged, what should have adapted has remained malignantly maladaptive and what should have been the agents of change and adaptation have been maligned and discredited as colonial imposition. Worst of all, what should have simply given way has been salvaged and juxtaposed to a threadbare modernity and then left in a state of mutually contaminating hybridity which we now refer to as postcolonial culture.

But whether in a state of obdurate traditionalism or hybrid neo-traditionalism, Africa under the spell of Africanism still comes across as a huge Dead Sea that refuses to give up its old waters, its millennial debris and excrement in exchange for empowering new waters or which prefers to absorb any incoming new waters into its already overladen old body. In Post-Africanism, we see Dead Sea-like Africa as dying fast in its ancestral or neo-traditionalist sea bed, weighed down by accumulated ancestral cultural detritus and urgently in need of a Post-Africanising intellectual heavy dredging work that can loosen its congealed nativistic waters and allow them to flow unhindered into the purifying living sea of global history and culture. In less figurative terms, Post-Africanism sees Africa as a continent that can no longer stand the ideological life support offered by various ideologies of Africanism [Négritude, Afrocentricism, African path, etc.] but which urgently needs to extract itself from them all so that it can reconnect more smoothly to the life-transforming forces that drive human progress in the modern global world. Under Post-African eyes, the persistence of cultural forms, and archaic traditions, including harmful ones should no longer be seen as proof of the vitality of native Africa and its heroic resistance against colonial vandalism but as evidence of what Africa failed to do, how Africa failed to act, to aid cultural evolution and a transition to modernity. Their continued existence proves our inability, reluctance or unwillingness to adapt to modernity.

Now, as already hinted, Senghor as the creator of Négritude and the artistic instigator of cultural nationalism, is totally complicit with the emergence and persistence of the Afrophiliac impulse in Africa’s dealings with itself and the world. With his heavy poetic embellishment of the ancestral past, he inspired the back-to–the-roots cultural Rousseauism that enthralled the Africa of the 60s to the 90s of the last century. He lavished so much poetry and artistry on the ancestral past that not only did it become attractive again but it inspired in the immediate postcolonial imagination an image of traditional Africa as the only possible cultural comfort zone, the eternal home of the African. His implicitly accusatory nostalgia of a lost pre-colonial world instigated in the nationalist generation an abiding loathing of colonization, Europe and modernity. Thus David Diop, a Négritude poet influenced by Senghor, referred to the colonizers as filthy vultures who came to violate the splendid ancestral sanctuaries of native Africa. [8] Senghor’s poetry had redeemed the past as well as the survived traditional world into a monument worthy of adulation, and prideful protection.

However, though Senghor with his Négritude poetry and thoughts largely inspired the cultural-nationalist generation, he possessed what this generation lacked, namely, a higher elastic force of life, a smarter world intelligence that enabled him to only artistically use Négritude rather than being bound by its theories. Senghor never turned Négritude into a prison house of Africanness because to him, Africanity was not a destiny but only a contingent resting place in Africa’s journey towards universality. Therefore the notorious passéisme of his poetry and ideas was mostly aesthetic-cultural in intent. His Négritude did not stop him from being the most enthusiastic Eurocentric modernizer. With many politicians and artists of the cultural-nationalist generation, the Afrophiliac impulse [the urge to love Africa and hate Europe] worked as a tyrannical and overzealous overseer of thoughts, imagination and acts. With Senghor, a smart advocate of tradition but passionate lover of modernity, Négritude was only a contingent tool of psychological self-reassurance, a cultural self-confidence booster. It did not interfere with Senghor’s real world’s work, especially the work of turning Senegal into a modern nation-state. In this, he, without shame or an inferiority complex, relied almost exclusively on French expertise; on Eurocentric knowledge and know-how. While others like Mobutu allowed Africanism to get into and dictate the political as the total Africanization of everything, Senghor never allowed Africanism to interfere with the Real-politik of friendship with Europe nor with the rational-scientific work of using European knowledge to prepare Senegal for economic and political modernization.

However, the real Post-African Senghor unfolds most eloquently at the frontiers of his total embrace of coloniality; his bold vision of colonization as a divine blessing, a providential gateway through which Africa will enter into world history. I have already alluded to his pro-colonial poetry. From such deep empathetic identification with the colonial apparition in Africa, with the pro-Europe ideas expressed in his subsequent writings and his political activities within imperial France, it becomes obvious that Senghor greatly approved of the colonization of Africa as something divinely programmed. Thus unlike his peers, he spoke of colonization, of Europe without resentment and with a great deal of gratitude sometimes bordering on awe. He experienced and revered Europe as the antithesis of Africa, as the model of what Africa ought to be. He deplored the brutality and racism that accompanied colonization but he welcomed the overall benefits that Africa accrued from the colonial enterprise. Thus his open embrace of modernity despite his love for African traditions, his open Europhilia and robust aspiration to universality, make him a good preparatory ground for Post-Africanism’s rupture with all paranoid forms of African identification claims as well as all cognitively dissonant forms of anti-coloniality. But then even this remarkably pro-colonial and pro-modernity Senghor must be first trans-valued, his ambivalences and contradictions resolved or selected out so that he can a genuine and creative Post-African mentor.

He saw in the colonization of Africa both the good and the bad; he deplored the bad and extolled the good. This dualistic view of colonialism, though more descent than Fanon’s monistic anti-colonial fanaticism, is still caught in an unhelpful disjunctive moralism that fails to capture the inner purpose of the colonial enterprise. In Post-Africanism we think that to fully appreciate that inner purpose, one must rise to a higher state of consciousness. One must be able to see it as an event in world history, i.e., in terms of the Hegelian idea of the world spirit and the cunningness of its march through history. According to Hegel, the history of the world is governed by a World spirit or Reason. This world Reason is responsible for moving world history from one stage to another. To achieve this movement, it does not operate directly but cunningly. [9] Great changes and movements will not occur until the greed and passions of world-historical men are activated, making them ready and willing to mobilize violence, cruelties and other immoral means to pursue their passion for self-aggrandizement. But while the great men think that they are only pursuing their selfish individual or national self-aggrandizement, world history cunningly uses them to achieve results that far exceed their initial conscious plans. Colonization as a world-historical event par excellence can best be understood today in Hegel’s world-historical terms [especially after the narrowly moralistic Fanonian discourse has only bred victims rather than free creative subjects]. Applying this Hegelian world historical narrative to colonization of Africa, one can see that it was here a case of World Reason instigating newly industrialized Europe to suddenly look outward to Africa for the purpose of their imperial self-aggrandizement. In the course of their greedy scramble for the largest piece of the continent, they ended up opening the vast and isolated continent first to itself and then to world history. Opening up Africa and connecting it to world history: such was the inner goal of the colonial enterprise which, through the cunning of history, was not really part of the initial passions that moved the selfish gold-digging colonial scramblers.

In the light of this Hegelian re-appropriation of Africa’s colonial moment, Senghor’s ambivalences look timid and not so smart. He cannot really separate his love for the benefits of colonization from the cruel violent means used to achieve them. He must take one with the other for one is the price paid for the other. Thus Senghor should love colonial Europe, not despite the destruction of old African kingdoms, but precisely because of this. In the logic of the cunning of world history, those old kingdoms had to be destroyed in order for Africa to enter a new stage of history. Thus Senghor’s theory of the positivity of colonization must be redeemed from the old disjunctive dualism because the cunning of reason in history has already dictated the organic interplay between great violence and civilizational elevation: one is required for the other to occur and cannot be conceived of without it. The awareness of this dialectical interplay and of the higher reason behind the colonial process renders anti-colonial tropes like enmity, opposition or duality either irrelevant or unhelpful. This is the awareness that drives Post-Africanism; it is the thinking that should take Africa beyond anti-colonialism to a stage of mind driven by the awareness of the interconnectedness of all events of history. At this stage, the driving force of thinking is no longer the old Afrocentric emphasis on the difference between Africa and Europe or the uniqueness of Africa, but on what should hasten the alignment of Africa with the universal forces and energies that drive global modernity. Indeed one of the pillars of Senghor’s thought was how best to hasten the insertion of Africa into what he called a universal civilization. But his idea of such a universalism was what was to result from the cultural métissage [cross-breeding] between Africa and Europe. In other words, Senghor was asking that Africa should carry African culture, i.e., its ancestral worldview, belief systems and customs, to a rendezvous of world cultures from which a cross-breeding will give rise to a genuine universal civilization. To us today, that sounds like suggesting that African juju [magic] should sit together with European science to discuss the modernization of Africa or the development of a new universalism. Whereas Senghor thinks that African cultures have a contribution to make in building a new universalism, for us Post-Africans, a more logical sense of world cultural evolution says that what we call African culture should first considerably yield to the culture and power of scientific rationalism before Africa can become a creative part of the current global universalism. Contrary to Senghor, it is Africa that should adapt to modernity; it is not modernity that should sit down and negotiate with Africa to determine the form and shape of universalism. Neither modernity nor globality can adapt to Africa. It was the delusion of cultural nationalism to have imagined that there could ever be a rendezvous of winners and losers to negotiate the next course of world history. However Senghor’s métissage formula seduced the cultural-nationalist generation but then it landed them in the current incapacitating hybrids which we call postcolonial culture. For us, the formula for universalizing Africa is extraction from Africanism rather than hybridizing African cultures with bits and pieces of modernity. Thus throwing the light of Post-Africanism on Senghor shows that his more positive embrace of the colonial legacy, his love for modernity, his friendship with Europe etc., all make him stand out among his generation as a great prophet of a future Africa that was going to need considerably more of modernity and less and less of Africanity. While the Fanon-inspired anti-colonial elite tried vainly to alienate or eliminate the colonial component of their subjectivity, Senghor knew wisely how to integrate the colonial shadow into a more complete, healthier modern subjecthood. He thus proved that it is possible to take Africa off the cognitive dissonance involved in having to constantly badmouth what you most covet. While the Fanonian anti-colonialist theorists and artists prefer to live their post-coloniality in a permanent state of such cognitive dissonance, Senghor manifested a much greater freedom vis-a-vis the colonial legacy. However to make him a truly inspirational voice of a Post-Africanity, one must jettison almost the entire Négritudist cultural-nationalist phase or face of his thoughts and art and then trans-valuate his métissage into a genuine Post-African universalism. This second part of Post-Africanizing him will involve enrolling him into a very crucial part of the Post-African agenda, namely, unlearning Afrophilia through a substantial de-Africanization of the mind. This program will concern mostly African art and will be elaborated in the section that follows.

Abdoulaye Diakité, Nommo albo bóg wody, rzeźba. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Daniel Bamigbade, Wielka maska, 2013. Rzeźba. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Braima Injai, Metafora, 2013. Akryl i pigmenty na płótnie, 150x150. Dzięku uprzejmości artysty.

Braima Injai, Twarz księżycowa, 2013. Akryl, pigmenty i kolaż na płótnie, 120x120 cm. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Post-African art vs Dak’Art

The ideology of Africanism led by Senghorian Négritude is usually credited as the source of what is called modern African art [as opposed to the traditional, pre-colonial art of Africa]. Modern art seems to have entered the African scene as a tool, a handmaid to anti-colonialism, cultural-nationalism and other forms of resistance to colonization. But if we look at modern art as the purveyor and repository of those very primal mental images and representations that followed immediately upon Africa’s colonial encounter with Europe, it becomes obvious that it was art that made the ideologies of Africanism possible. Modern African art is not the by-product of anti-colonialist cultural-nationalism; it was the first major form of response to colonization. It can be said that it was art that created Négritude rather than Négritude that created modern Africa art. Africanism, a resistance theory of the positive uniqueness of Africa’s civilization, would not have taken its emotionally binding form and dramatic impact if poems like “Femme noire”, “Africa my Africa” or stories like Things Fall Apart; Weep not Child; House boy [10] had not already furnished the searing primal images and emotions, and dramatic mental representations of traumatic colonial vandalisms, as well as the heroic resilience and beauty of Africa’s native essence, that seized hold of the then near formless imagination of the people and triggered both anti-colonial and cultural responses that solidified into cultural nationalism or Africanism. With his daring and striking formal style, searing images and soul-stirring tales, the artist was the first to be able to tame and temper the brutal uncanniness of the white man’s ghost-like apparition among the natives; he provided these images with, some meaning along with many strange sayings and doings of the colonialists among the tribes. I recall these both to underscore the importance of art in the birth of African ideology and also the role of art in the petrifying and subsequent perversion of this ideology. My thesis here is that, as art largely created Africanism or Afrophilia, art can also, if Post-Africanized, play a crucial role in the battle to disentangle the Afrocentric imagination from the traps and dangers of a hypertrophy of Afrophilia.

Today Dak’Art under the shadow of Senghor the Négritudist, has come to symbolize both the original soul of modern African art and the attempts to exceed its inherent Afrophilia in a bid to connect performatively with the global art world. In this section I want to read the Dak’Art stage of modern African art in the light first of its Senghorian old ghost and then against the new background of a Post-African art theory. In other words this section is about both a critique of African art and a bold attempt to take it out of the Afrophiliac trap.

I have just postulated that modern African art made cultural-nationalism possible; it was the condition of ideological possibilities that came to coagulate under the umbrella term Africanism. Art shaped the imagination by supplying the trigger images that gave these theories emotional foundation and political efficacy. However, once these movements, especially Négritude, African personality, anti-colonialist cultural-nationalism, African authenticity, Afrocentricism, became full-fledged theories and practice of the African way, they seemed to have suppressed all traces of their aesthetic origin and rather turned art into a subservient tool. African art after midwifing the birth of the African ideology, became a handmaiden to the latter. In the spirit of nationalism, anti-colonialism and cultural Africanization that took possession of Africa in the 50s and 60s of the last century, art -music, theatre, dance, painting cinema etc. -became mobilized in the service of the African cause and seems to have justified its existence almost exclusively on this basis. In those early days of militant Africanism, art was about showcasing the Africanness of Africa; it was a vast and endless curating of the wonders and splendors of original Africa with a view to re-assuring us of the validity and beauty of African civilization, and at the same time, denouncing the arrogance and pretensions of colonial Europe that had dared to badmouth a civilization blessed with such native splendors. Art wasn’t so much about creating but confirming, re-discovering, celebrating and showing off Africanity. Art became infinite self-confirmation and self-celebration. Creativity, imaginative novelty became secondary because it was a matter of making explicit and radiant again, revalorizing what was already there or what had been disfigured, concealed or partially expunged by colonial vandalism. In Ngugi’s terms art was about re-membering all that had been dis-membered by the colonial ‘cultural bomb.’ [11] Art in cultural-nationalist Africa became no longer what a creator concocted from the inner riches of his imagination to shock or de-familiarize the world around him but whatever hitherto hidden, mis-recognized layer of Africanness had to be brought to light and celebrated. Thus to the Post-African observer looking back to the heyday of the African ideology, early modern African art comes across as mostly an infinite rehearsal of Africanness. But what was this artistic Afrophilia all about? What was the nature of this Africanity that early modern art set out to perpetually celebrate and showcase?

The underworld of the Afrophiliac ideal that modern African art exalts is in reality a dungeon of old instincts, outdated ways and beliefs that survived the archaic juju-centric, pre-colonial tribal world, i.e., those aspects of traditional life that refused to yield to evolutionary mutations dictated by Africa’s encounter with modernity. Although rehabilitated and clad in a heroic resistance toga by anti-colonial cultural nationalism, these very old ways which constitute Africanity are precisely what are sabotaging everything Africa does to modernize, normalize, and develop. Consider Juju or magic which is a constant feature and the unspoken worldview backdrop to most popular art forms in Africa especially popular cinema such as the Nigerian Nollywood. Although Nollywood covers a large variety of themes, the typical Nollywood block buster movie thrives on a celebratory wanton display of the juju and the power of the occult in Deep Africa’s daily life, including politics and economic success. The truth is that magic, or African juju that art makes so much of, expresses the captivity of the mind in a very archaic level of human consciousness; it marks the inability of the human mind to liberate itself and evolve into higher forms of consciousness. The persistence of the magical and the tendency for African art to glamorize it mark the reluctance or inability of Deep Africa to free itself from the very chains that held our ancestors bound and that made them so easy to defeat, enslave and so easily colonizable in the first place. When modern art forms like Nollywood, painting and theatre etc., choose to emphasize and highlight the magic-mythic elements as the very foundation of African culture and the native worldview; when the artist lavishes so much artistry in depicting these archaic non-evolutionary elements of Africanity, then modern art is actually deliberately spreading flowers over the very chains that have bound Africa, making it difficult for it to grow and prosper like on other continents. While I will revisit this later, I want to talk about Dak’Art as the embodiment of the good and the bad in modern African art.

One of the secret charms of the Dak’Art biennale is that it is always mired in very instructive paradoxes. The curator of this year’s show Simon Njami speaking on the theme of the main exhibition, mentions the term ‘re-enchantment.’ The main goal of this year’s Dak’Art is to re-enchant Africa. He says: ‘If we succeed in re-enchanting Africa, we can re-enchant the world.’12 This would mean that Dak’Art, though an attempt to globalize African art, is still fully embedded in the same old cultural-nationalist spirit that presided over the emergence and growth of modern African art. The aim of cultural nationalism was to rescue colonized Africa from the ‘cultural bomb’ [13] that colonization had just detonated on Africa and reinstate her fully in her millennial nativity. Colonization had attempted to disenchant Africa by driving away tribal magic, dethroning ancient deities and burning their altars. Cultural-nationalism sought to re-enchant Africa by rebuilding the burnt altars and re-infusing Africa once again with magic and myth. To them the soul of Africa lies in its millennial magic-mythic consciousness. To destroy it means to deprive Africa of a soul, to destroy Africanness. Art’s primary function was to re-enchant the colonially dis-enchanted sites of Africanness. If today, the curator still talks of using art to re-enchant an already over-enchanted continent like Africa, then it may be save to say that Dark’art, despite all the borrowed props of globalization, is still fully stuck in the re-tribalizing, de-modernizing forces of early cultural-nationalist art. Dakar is still the art of Négritude merely putting on borrowed ill-fitting new garments.

However, Dark’Art is also famous for exhibiting, even showing off the globality of its concerns. Though usually composed of a cast of African and African Diasporic artists, it ritually gathers together art critics, theorists, collectors from all over the world. The theme of the 2014 show was ‘Vivre ensemble’, a coquettish allusion to the Senghorian ideal of a rendezvous of world cultures, [to which Africa would bring the gifts of rhythm and emotiveness] a celebration of hybridity, of cultural métissage. It also gestures mostly to what can be called the globalization of African art. On a closer look however, such globalizing or postmodernizing gestures of Dark’Art seem more stage-managed than real. It does not signify an honest attempt to release modern African art from its Afrophiliac tribal box into the global vortex of human creativity; it does not translate into the global mainstreaming of African art; these artificial globalizing props seem to arise out of the necessity to attract international funding. Dak’Art in reality is still steeped in Africanism, seeks a specific victimized African visibility and pursues the same old Afrophiliac affirmation/accusation agenda. Indeed Dak’Art, in spite of its false globalizing gestures, is still the opium den of Afrophiliac art, the art of the tribal comfort zone. It is a tame center of self-congratulatory art where African artists, critics and their foreign blasé postmodern neo-exoticists ritually meet to exchange compliments and savor old anti-colonialist or anti-globalization clichés. Don’t expect from Dak’Art any bold, trail-blazing experiments in art or theory, nor searing novelties that can compel the African art question to be posed in any unheard-of-ways. Similarly Dak’Art cannot be seen as a laboratory of African modernism for there can be no true African modernism when modernity has only aborted in Africa. Likewise the conditions for the globalization of art in Africa do not yet exist because Africa has not yet fully entered global modernity. Still perched on the outermost margin of the global economy and in the absence of a successful scientific-technological modernity, Africa’s art or African modernism is limited to perpetually complaining about Eurocentricism, globalization and staging all manner of resistance stunts in lieu of creation. Smooth Nzewi, a famous art scholar and curator of 2014 Dark’Art, recently complained that the global art world does not seem to be able to overcome the tendency to pigeon-hole African art as Africanity [The burden of Africanness]. [14] The question is what stops African art from being universalized? It is not racism as African critics are wont to allege; it is simply because Africa is yet to become a full member of the global world. The cultural people deceive themselves when they think that there can be cultural globalization without economic/technological globalization. That is why African modernism is a fraud because there is no modernity against which the African artist could develop artistic modernism [artistic modernism considered here in terms of its European genealogy as the revolt against modern industrial culture]. Dark’Art is the emblem of the unresolved schizophrenic conflicts at the heart of modern African artistic and cultural self-understanding. Unable to escape Senghor’s Négritude shadow, it is still stuck in cultural nationalism but unlike Senghor, it has not been able to fully integrate the colonial shadow. The African Renaissance Monument which provides the artistic backdrop to both Dakar and Dak’Art can be said to symbolize the basic schizophrenia of African modernism. This is a huge monument showing an Africa rising up proudly into the sky in an accusatory defiance of the old imperial world that had sought to crush it. Looking at it, I can hear the words of David Diop’s famous poem, ‘Africa my Africa’ [15] re-cast in stone and marble. Though mightily showing off a victorious and proud Africa rising up from the dust, it is still apparently recounting the sorrows, the agonies and suffering of Africa at the hands of Europe. To be sure it is celebrating the successful renaissance of Africa but in a tone of victimhood, vindictiveness and a basic inability to forget. But victimhood, impotent vengeance and the inability to forget are the shackles around the feet of a future-facing Africa that aspires to modernity. They are the source of the adversary impulse that still afflict not only the art and thought but also the development work of Africa. The monument is the symbol of a Dakar trying to serve two masters at the same time: being a temple of Africanism and a magnet of cultural globalization. It is also Africa limping to modernity on two bad legs: one leg stuck in tradition and the other groping for science and rationality.

Thus the art of Dark’Art steeped in Afrophilia and anti-colonial resistance, floats above the real cultural needs of a stagnant, confused and hungry Africa. Such needs include taking Africa off the life-support of old unworkable self-narratives such as Africanism/anti-colonialism. This will form the subject of the next section.

Post-African Art Against Dak’Art

The starting point of my reflection on a Post-African art is that the old mission of African art is exhausted because the mission of cultural nationalism and anti-colonialism which that art served is totally exhausted. The African story, from which both art and cultural nationalism derived their source and meaning, is no longer good enough for us. We are not that single story for we are infinitely more than our Africanity. In the Post-African battle to save Africa from itself, the emancipation of African art and of the artistic imagination can be a good place to start. Since it was art that first created the dense web of negative images and emotions that enveloped the African imagination in the narcissistic fog of Afrophilia, art can be called upon to initiate our redemption from it. Thus the chief mission of art in the Post-African era is to aesthetically re-educate the modern African out of the snares of cultural Afrophilia and to prepare him to fully embrace and exploit the boundless creative energies of the infinite possibility universe to which we are joint heirs with others. The driving question of Post-African art is: now that Africanism is culturally and intellectually exhausted, what would a modern African art be like when it finally stops having the presuppositions of cultural-nationalism and anti-colonialism worked into its founding motifs, form, and content? In other words, what will art from Africa be like when the artist has successfully Post-Africanized his imagination? I think that an artist delivered from Afrophilia and invested with Post-African consciousness will naturally have no choice but to transpose and transfigure everything about Africa into the new spirit he carries. He will no longer paint, draw, make films or write in the oppositional frame of Africa against Europe or in the cultural-nationalist imperative to prove a point about African culture, or African capacity to create his unique modernism. All those oppositional structures of the imagination that engendered only resistance art or the art of perpetual self-approval will disappear leaving the creative imagination uncluttered and free once again to roam the uncharted areas of an Africa no longer imagined as a world apart but a creative part of the global whole. He will seek for his art nutrients from every culture provided he creates what can lift Africa, build inter-cultural bridges and benefit mankind as a whole.

Consequently, Post-African art is about the search for counter-Afrophiliac artists who through their Post-African novelty of touch and vision will be able to untie the Négritudian Gordian knot of African culture in the singular; the new artists who will have the will and the courage to break the stranglehold of a harmful Afrocentric master-narrative on the imagination of creators from various parts of a vast and diverse continent. And what is this African culture that has haunted and tortured art from Africa? An abstraction without any performative meaning, without substance, just an old anti-colonial opinion, followed by a collection of clichés about some archaic ancestral ways, unadaptive worldviews and belief systems and a lot of bad choices on the part of AU leaders who mouth it [plus a lot of boring silly art by artists who swear by it]. There can be no greater proof of the inanity of the African culture formula than the total disasters that have accompanied nearly all projects both economic and political that were built on the basis of African culture e.g. the Africa path to development, African solutions, the African Renaissance. The Post-African artist must have the courage and the will to break out of the strangle hold of this concept, for with this concept, the artists continue to spread flowers over the very chains with which we have bound our imagination, our minds and our ability to develop. How can the formula for our stagnation continue to be regarded as the badge of our dignity and pride? The Post-African artist must have the courage to despise that formula because what does African culture stand for if not the absence of thinking, or the thinking-stopper, the loss of imagination, the cowardly repose in a wretched comfort zone of life. All in all, the tyranny of African culture fosters the abdication of thinking, creativity and growth. In the presence of African culture, you can no longer think, dance a new dance or imagine new things; you can only imitate, copy and prostrate in infantile reverence. The artist must burn such reverence so that he can finally come into his own and create his own Africa. If there were Africanness as the totality of African cultures and values, what will the artist create? Africanity is the death principle of the imagination of Africans; it is about the premature sclerosis of a people’s creative genius; it is the encasing of one’s mind in iron-cast boundaries. So Post-African art is art that has broken out of the singular box of African culture, African identity, African way of life. It is also art that has overcome the imperative to defend Africa: there is nothing to defend Africa against; Africa does not need a defense. The people of Africa are free to create as many Africas as they want. The Post-African great liberation is this: there is no Africanity to uphold, no African identity to protect, no great African cultural imperative. If there were any of these, it would have been totally exhausted by now. We have overwritten and spoken ad nauseum about this Africanness thing. The question is, now that the artists are free from this old burden, what will they create, how will they write and paint and draw and dance? If indeed they are artists, they will continue to create, write and paint. For the death of Africanity cannot correspond to the death of their imagination; it will only occasion a renewal of that faculty. If they were only ideologues and imposters, they will certainly look around for whom to blame for their exhaustion; for in their case, the limit of their Africanity correspond to the limit of their creative imagination.

Thus one of the chief functions of Post-African art is redemption from Afrophilia. Post-African art is not the opposite of Négritude art; it is the absence of Négritude, of any form of Afrophilia in the imaginative universe of the new African artist; it is the overcoming of the entire psycho-cultural ground that had birthed Négritude. Afrophilia as we know is a compound of nativist narcissism and anti-colonial paranoia. Thus the second leg of redemption from Afrophilia involves reconciling with coloniality. Like Senghor, the Post-African artist says yes to colonization but unlike Senghor, he says no to cultural nationalism for he understands the importance of creative destruction in colonialism’s work in Africa. He knows that part of the civilizing mission being the attempt to raise the humanity of the African from the level of homo tribalis to a higher humanity, involved the relentless destruction of all that was holding the African in the tribe, in magic and human sacrifice. It involved the conscious destruction of that which had been blocked during a long period of isolated living, natural and cultural evolution. Frozen traditions, maladaptive customs and beliefs had to be eradicated, replaced or reformed. This was indeed destruction but creative destruction, destruction of the archaic so that the life-giving new will step into the breach. Post-African art draws from this overcoming of anti-colonialism and anti-Eurocentrism, a creative new energy to be able to align art with the positivity of modernity and of friendship with Europe.

In conclusion, let me say that with Post-Africanism I have touched the hidden sore spots of a suffering and un-growing continent that does not dare to look in the eye, the real roots of its sufferings and regressions. But Post-Africanism is not another form of Afro-pessimism. It is actually the very opposite. My point is that armed with the Post-African awareness and self-awareness, to be African today is the greatest, the most exhilarating challenge. We know that most other continents have already finished their world’s work. Africa has not even really started hers. We took a detour that caused us to misrecognize and bungle ours. With Post-Africanism we have realized our wrong turns; we have come back from the non-transformative excursions, we are about to begin our work in the world. It is a great blessing to live for and build the Post-African future. We have work to do and that work demands the total mobilization of all our energies. There is no dull moment in Post-Africanity unlike postmodernity where everything, including art, is about the exhaustion of man, boredom and fatigue. Post-African art, unlike postmodern art, is the promise of a new birth, the birth of a new Africa over the ruins of old thoughts, old images and old narcissistic art.

BIO

Denis Ekpo is a Professor of Comparative Literature and the Director of the Comparative Literature Program, at the University of Port Harcourt. A cultural theorist he has developed the concept of Post–Africanism. He was a member of the advisory board for Third Text from 2004 to 2012 and is the author of two books: Neither Anti-imperialist Anger nor the Tears of the Good White Man (2005) and La Philosophie et la littérature africaine (2004). He has participated in many art projects and is currently working on a Manifesto for Post-African art.

*Cover photo: African Renaissance Monument, Dakar (2006-2010). Photo: wikicommons.

1. Elizabeth Harney, In Senghor’s Shadow: Art, Politics and the Avant-Garde in Senegal, 1960-1995, (London:Duke University Press, 2004).

2. Codesria, Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, headquartered at Dakar, is a foremost Pan-African research center noted for a rather militant Afrocentric and anti-colonialist approach to the production of knowledge in Africa.

3 “Femme noire” [Black woman] is Senghor’s famous poem in which he extols the virtues of the African woman who in her nakedness and darkness, embodies the eternal beauty and values of Mother Africa. It is found in the collection Poèmes, (Paris: Editions Seuil, 1964), 14.

4 “Neige sur Paris” [Snow on Paris] is in the same collection Poèmes, 20.

5 Prière de paix [Prayer for peace] Ibid, 90.

6 Denis Ekpo, Speak Négritude but Think and Act Eurocentric: The Foundations of Senghor’s Political Philosophy, (Third Text, 2010).

7 Jean-Paul Sartre, Black Orpheus, (Paris: Présence Africaine, 1954).

8 ‘The Vultures’ is the title of David Diop’s poem from his collection Coups de pilon, (Paris: Présence Africaine, 1956), in which he deals hammer blows to colonization seen as the invasion of Africa by white vultures.

9 The idea of the ‘Cunning of Reason in History’ is developed in Hegel’s Philosophy of History, (New York: Dover, 2004), section 3 sub-section 36.

10. Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe, Weep Not Child by Ngugi wa thiongo, House Boy by Ferdinand Oyono are the canonical anti-colonial novels that created strong emotional space for anti-colonial as well as cultural-nationalist theories.

11. The idea of colonial culture as a cultural bomb that turned African culture upside down comes from Ngugi wa Thiongo. It was first expressed in his famous essay Decolonising the Mind, 1986.

12. Simon Njami, ‘Mon plan pour Dakar’ in thisisafrica.me.

13. Ngugi wa Thiongo, op cit.

14 Smooth Nzewi, ‘The burden of Africanness’ okoyaafrica.com

15 ‘Africa my Africa’ published in David Diop’s Coups de pilons is a charismatic poem in which David Diop pits the tragic fate of Africa at Europe’s colonial hand against the heroic resilience of a phoenix-like Africa that rises up from the very mud of her sufferings to the greatness of an earned freedom.