Simon Njami, Artistic Director of the 12th Dakar Biennale, in conversation with Dominik Kuryłek, Bartosz Przybył-Ołowski and Alicja Rogalska. The conversation took place in May 2016.

DK/BPO/AR: Currently there are about 200 art biennials in the world. Their role is to strengthen the contemporary ‘creative industries’, but also to create new definitions of social, political, and cultural relations in our globalized world. You were the curator of the African Pavilion at the 52 Venice Biennale (‘Checklist: Luanda Pop’) and now you have agreed to be the curator of the Dakar Biennial. Why do you find this model of presenting art interesting, even though it has its origins in colonial thinking and the beginnings of 20th century capitalism?

Simon Njami: I don’t believe that biennales are there to create new definitions of anything. At least in the West. It is a kind of a story that is repeated every two years with different words. Among the 200 biennales that you’ve mentioned, 90% are in the West. And if you look at them carefully, you will find that most of the time, it is the usual suspects. I think that a biennale is important for ‘emergent countries,’ as they are called, because it should go beyond the usual discussions about art. On the contrary, it should function as a tool to get rid of colonial preconceptions.

How can this be achieved in practice? And what kind of non-artistic discussions should it initiate?

It is all about politics - politics of the self, politics of education, politics of display. The biennale was organized in such manner that it could tackle all the issues related to the social and citizenship; beyond the borders of a State. From children to adults, everyone could sense that art was not only about art but about rethinking the world and our belonging in it.

You have been working on shows like this since 2004, for example ‘Africa Remix’ or the aforementioned African Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Is organizing exhibitions that aim to present “art by artists from Africa” not too exclusive or too broad in its very principle?

I am not presenting African artists but artists from Africa. You could have mentioned as well ‘The Divine Comedy.’ I am interested in deconstructing ideas. Building theories. And for that, the African continent seemed to me to be a very good field to work in because everything was to be deconstructed and reconstructed. Africa functions for me as a metaphor. What I experience there, I can use anywhere else. If you look at the recent story of global art, in the early 90s it was as if Africa didn’t exist. I think my work has contributed to changing this situation and nobody serious would think of putting together an international art event without African artists. I have recently done two shows. A solo show of Santu Mofokeng (South Africa) and one on the Walther collection. In both cases, it was not Africa that I was interested in, but the material I was dealing with. What obsesses me is what can be said with art.

What were your aims when decided to work on the Dakar Biennial this year? Why is that particular context so interesting to you that you accepted the invitation to be its main curator?

Dakar is an old lady. The oldest on the continent. I think it was time to give it a new youth and new meaning. It should not just be a biennale for Africans, but a biennale on its own terms. I have been trying to show this with my program by inviting, for instance, five curators who are non-Africans (from Korea, India, Brazil, Spain, Italy) and one from the continent. I see the biennale as an open space for discussions that should not be aimed only at Africa. I see the biennale as an educational tool. This is why I have implemented a lot of programs in the city. So that the citizens of Dakar can be part of the event. There were a lot of things to be corrected. I won’t succeed in doing so this year, but I want to point towards a direction for the future and for other art events on the continent.

I have taken new spaces precisely to show that there is a new direction. Once again, I didn’t invite African Artists. Of course, all those who are included in the pan-African show have ties with the continent. But they all have diverse experiences, backgrounds, and stories. I want people to feel that there is no such thing as Africa. It is a vast continent with many stories, different cultural and political policies and different scenes. Instead of showing uniformity, I’m seeking out diversity, to reflect the reality of the continent. All forms of art are invited, from installation to video, photography, and so on with a special emphasis on performances this year.

Safaa Mazirh, Bez tytułu, 2013. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Héla Ammar, Purification III, 2010. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Lavar Munroe, A Heroe's Journey, 2013. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Fatima Mazmouz, Le Corps Pansant Super Oum, 2009. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

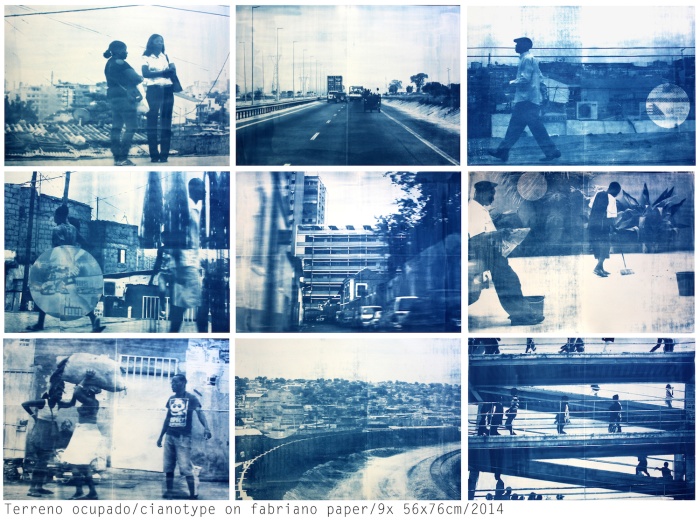

Delio Jasse, Terreno Ocupa, 2014. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Ala Kheir, Revisiting Khartoum, 2015. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Aida Muluneh, Denkinesh Part Three - The World is Nine Collection, 2016. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Victor Ehikhamenor, The Delegate, 2014. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Nana Poku, Cheremeh la Disparition, 2015. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

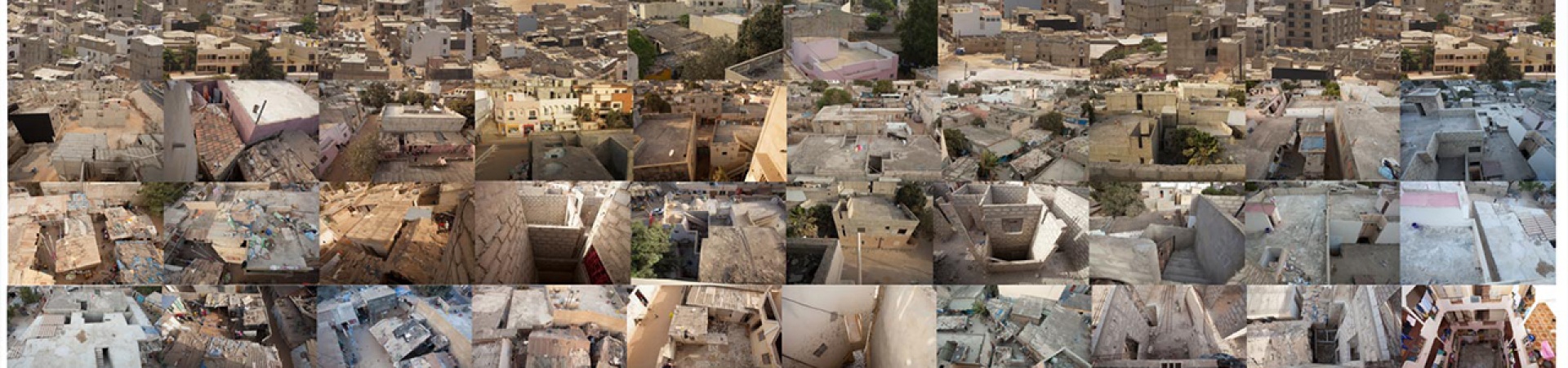

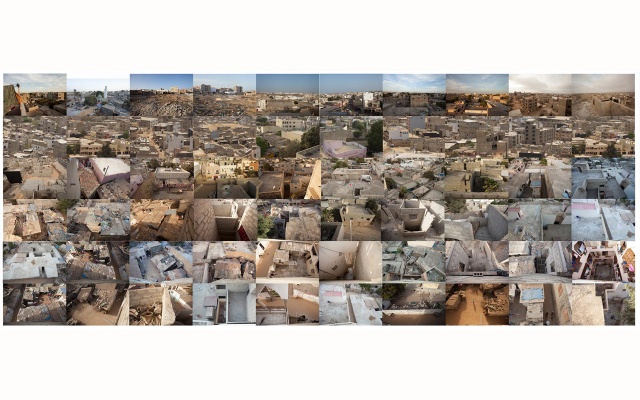

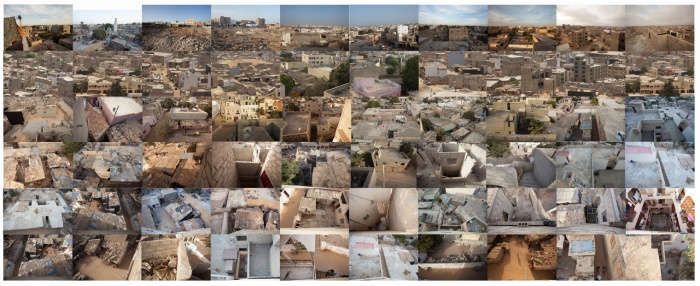

Sammy Baloji, Fraktale Ouakama, 2015 [Joe Ouakam to prawdziwe nazwisko artysty Issy Samba]. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Aida Muluneh, Denkinesh Part one - The World is Nine Collection, 2016. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Aida Muluneh, Denkinesh Part two - The World is Nine Collection, 2016. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

What is your first memory connected with the city?

I guess it was during what was to become the biennale. Then, it included literature. I immediately enjoyed this particular atmosphere that you could not find anywhere else in Africa, not, in fact, in the world. It was blooming with energy and ideas. Probably the legacy of what Senghor had been trying to plant in his citizens’ heads.

In one of his songs Salif Keita draws some loose distinctions between cities. He compares Dakar (and Johannesburg) to New York. Do you see this connection?

Salif Keita probably comes from a village somewhere in Mali. If not, he would know that Johannesburg or Dakar have nothing in common with New York, nor with each other.

And what’s the most exciting thing about working with Dakar’s urban structure?

The organized chaos. The mix between the colonial order and the contemporary urban attempts to remodel the city.

And what about Paris, is it still a strong reference point for art in Dakar, or maybe the focus has shifted in favor of Joburg, or elsewhere in another direction?

I think the US is the reference. And in that sense, one can say that Africans have become (unfortunately) global. Paris holds no attraction anymore, probably because nothing is happening in Paris that concerns them.

How are you going to connect the international and pan-African aspect of the biennale with the local art scene?

Pan-African already means international. So I don’t see any formal difference between contemporary artists. The location, the place they come from, is a mere accident. What interests me is what they have to say and how. The confrontation between African and non-Africans has only one goal in my eyes - to show to everyone that art, even if rooted in certain practices and histories, goes beyond geography.

Are you going to refer somehow to the legacy of the subversive local art collective tradition – Laboratoire Agit’ Art, Tenq, Huit Facettes?

I did not need to refer to them. They are alive and everywhere. Their legacy can be seen in the work of every Senegalese artist. I would not call them subversives, simply avant-garde. And, as you know, there is always a taste of subversion in the very notion of the avant-garde. This year, somebody like Issa Samb, to whom I have paid a tribute, was very active.

For many years, as a writer, you have been exploring the "hybrid" identity of those who identify with Africa. Does your literary practice and biographical experience inform your curatorial work?

For me curating is just another way to write. As in literature, I like works that pose questions, that force us to go beyond our comfort zones. When I curate, I act as a writer who tells a story. All my reflections are always translated into my exhibitions. Through the concept, of course, but also through the display of the work. For this edition, I had an ancient courthouse (a magnificent building) reopened for the what we call the “international exhibition.” I guess the success of Dakar 12 was partly due to the way we brought back this part of Senegalese history to life.

How is the Dakar Biennial financed and does it receive funding from the European Union? How is it possible to remain independent in terms of curatorial and artistic creativity and criticism?

This is one of the preconceptions that is making the rounds about the biennale. There is not a cent (at least for this year’s exhibition) that comes from the European Union. This is not to say that I would refuse their money. I have directed the Bamako Biennale for ten years 40% of whose budget came from the UE. I can promise you that nobody has ever told me what to show or how to run the biennale. The main funder of the biennale is the State of Senegal and I can tell you that it makes it much more complex than if the money were coming from somewhere else. If you look at the Western biennales, most of them are funded by banks, collectors, galleries, and private companies. Do you think they have a greater or lesser freedom?

Well... Is this freedom of content not an illusory one?

Freedom is always a fight we have to take on. Nothing is given. And nowadays maybe more than ever. You just need to look at the world around you. It would be, indeed, illusory to think that we have achieved any kind of freedom. Every single day, we need to go out there and to tell our stories, no matter if the “powers that be” don’t want to hear them. Especially if the “powers that be” want to silence us.

Instalacja Biliego Bidjocka, 12. Biennale Sztuki Współczesnej Dak'Art, 2016. © Marie-Ann Yemsi

12. Biennale Sztuki Współczesnej Dak'Art, 2016. © Marie-Ann Yemsi

Folakunle Oshun, United Nations of Jollof, instalacja, 12. Biennale Sztuki Współczesnej Dak'Art, 2016. © Marie-Ann Yemsi

Nail Boutros, Sen, instalacja, 12. Biennale Sztuki Współczesnej Dak'Art, 2016. © Marie-Ann Yemsi

Folakunle Oshun, United Nations of Jollof, instalacja, 12. Biennale Sztuki Współczesnej Dak'Art, 2016. © Marie-Ann Yemsi

Both Poland and Senegal were under Soviet influence which was then followed by the introduction of free-market reforms in the 80s and 90s. Is the legacy of that ‘transformation’ something you find important?

You can’t compare Senegal with Poland. Socialism in Senegal was light and Senghor never lost his privileged relationship with France. The idea of socialism was closer to that of François Mitterrand’s than to that of Gorbachev’s. Poland was still a Soviet Satellite when Africans were struggling with the reality of a world led by the real politik and the cynicism of Capital. What has remained is a certain idea of the welfare state. Senegalese are very attached to social progress and democracy.

The Dakar Biennial is an important element of Senegal's cultural policy, one that first originated in the political and cultural strategy as established by Léopold Sédar Senghor. Senghor in an original way combined the Négritude philosophy with Francophilia, whilst cleverly utilizing the colonial mechanism of mimicry, which you problematize in your books and curatorial activities. Do you think the Dakar Biennial has a chance to become an impulse to critically rethink not only global politics, but also the political, economic and cultural situation of Senegal, that has been dominated since the 90s by neoliberalism?

The main show is called “Re-enchantments” and the title was inspired by the work of the German sociologist Max Weber who stated (to make a long story short) that the illusion of progress has handicapped human development, transforming everything into a form of rentability and technology. I want to tackle that issue and find out how we can bring humans back into the center of the equation. As for the symposium that I have commissioned, it will be dealing with the notion of non-alignment and how to invent new ways that would not be an imposition on the New Colonialist models. Events are often the result of the reflection that they were based on. You mentioned Francophilia, for instance, and I will oppose that - even if we restrict ourselves to colonial languages, in Africa, as a whole, four are spoken.

Can you talk about any examples of artworks that deal with the re-enchantment you refer to? Is there a space for post-humanism in your vision of re-enchantment?

I don’t like this notion of post-humanism. I don’t like all that “post” stuff. Re-enchantment, to me, is about revolution. It is the will to change the established order and to bring, precisely, humans into the center of our preoccupations. The work of Bli Bidjocka, for instance (among many others but I can’t cite them all) is a good example of what I have been trying to say.

How about Senghor’s legacy and his dreams for the future of the continent? Can his influence be seen in program of the biennale? For example, “The City in the Blue Daylight”?

His dreams, yes. Because his generation has failed to fulfill them. I borrowed the title of the biennale from a poem of his. I wished to tell everyone that what needed to be done in the early 60s still needs to be done today, and that it is everybody’s duty.

In your writings and interviews you often criticize the postcolonial perspective as “freezing” the identities of the former colonized and the former colonizer and prevents transcending binary schemes. How can curators and artists interested in collaborating with artists from Africa escape the traps of postcolonialism and neocolonialism?

Once again I have invited curators from different parts of the world who share the preoccupations about the Center and the Periphery. What bothers me with postcolonial studies is that the former so-called Center is often given a major role. I am not interested in that. I am interested in experiences that are trying to break away from this binary reflection. I want to claim that the Center is where I am and not where I am told it is. All the wretched of the World (to quote Fanon) share the same colonial experience. They have all been trying out strategies to get away from this past. I want to put all those experiences together and find out what comes out of it. A theory must be thought (as Deleuze would say) for a given space, and it has to be efficient. I consider theory as a tool for changes. Not as a vain scholarly exercise, which it often happens to be. Africa gives me the chance to be a living laboratory.

How would you define “contemporaneity” with regards to the art of artists identifying with Africa, especially the ones you invited to participate in the biennial?

There is nothing particularly African in the artists that I show. This is an old ethnographic view. They all are, for better or worse, their own people using the techniques of their time. But art is created out of a context and an experience. That’s what makes any given piece unique. When it is rooted in a certain way of telling stories. That is what the world, outside of the so-called Centers, can bring - another philosophy and sensibility. For instance, the proposition of the Indian curator precisely deals with authorship and individualism. The project that he presents was created by more than ten artists and unsigned. Every space in the world has it own rhythm. This is what it should show to the others. Not some bad cut-and-paste attempts.

Currently more and more people in the world realize that they are being colonized, not as much by the Global North, but by an increasingly aggressive global capitalist system, that makes us into slaves of profit-oriented models of behavior with a small percentage of beneficiaries. More and more people are looking for alternative forms of political action. Have you ever considered developing other mechanisms of artistic, curatorial, generally cultural actions that could lead to escaping the vicious circle of supporting global neoliberalism and neocolonialism?

This what I am trying to do every day. And yes, you named it. The very super colonialist nowadays is not recognizable because he is hidden under the intangibility of Capital.

What would a truly postcolonial and postcapitalist world look like, could you share with us your personal utopian vision of the future?

I prefer the term post-colony, as used by Achille Mbembe because it supposes a rupture that I don’t hear in postcolonial. Since you are asking me for a utopian vision, it would be a world, an equity, and mutual respect where people will be able to practice what the French poet Arthur Rimbaud once shouted: “I is another.”

BIO

Simon Njami is a writer and an independent curator, lecturer, art critic and essayist. Njami is the co-founder of Revue Noire, a journal of contemporary African and extra-occidental art, and the Artistic Director of the 12th Dakar Biennale, in 2016. He was the Artistic Director of the Bamako Encounters, the African Photography Biennale, from 2001 to 2007 and curated the exhibition Africa Remix, as well as the first African Pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennale. He recently curated the exhibition The Divine Comedy or Après Eden at La Maison Rouge, among others.

*Cover photo: Sammy Baloji, Ouakam Fractals, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.