“Dakar, an interesting African metropolis? Without a doubt! Brain and practically the lung of Senegal? Definitely! But a filthy city! And pretty disorderly in a lot of ways. Still an angel passes by whispering to whomever will listen: “And the crisis? And…” Even to a relatively “unobservant” witness the streets of the capital offer a spectacle at once nonchalant, extravagant, and even suspiciously insouciant. He might become jaded by seeing such a seemingly jumbled reality through this slightly deforming prism.”

— El Hadji Sy, Issa Samb, Ass M’Bengue, Memory of the Future, Laboratoire Agit’Art

“The geographic expansion of Europe and its civilization was then a holy saga of mythic proportions. The only problem, and it is a big one, is that as this civilization developed, it submitted the world to its memory...”

— Valentin Yves Mudimbe, The Idea of Africa

Contemporary Senegalese artist El Hadji Sy has had a long and prolific career. From his earliest, groundbreaking works in the 1970s to his contemporary, international exhibitions, he has shown great courage, ingenuity, and activism. Sy’s interdisciplinary practice as a painter and curator stands out as both emblematic and singular in the context of postcolonial African art. A cultural activist who has worked and lived in Dakar all of his life, Sy’s work has also been exhibited internationally since the late 1970s. Praised by Léopold Sédar Senghor, the poet and writer who became Senegal’s first president in 1960, after independence, Sy is equally known for his critique and defiance of cultural politics under both Senghor and his successor Abdou Diouf. In his capacity as a cultural activist Sy continues to challenge the authorities and to fight for the autonomy of Senegalese artists.

Sy’s connections to Dakar and post-independence Senegal are crucial. Sy’s art indeed emerged mostly from this Sub-Saharan African country, marked both by a transnational history of slavery and colonialism and by its cultivation of artists and thinkers. Senghor believed culture would save Africa, and he actively promoted the status of Dakar as a major cultural and artistic center of postcolonial Africa. Senegal is also the home of the sculptor Ousmane Sow and the filmmaker Ousmane Sembène. Sembène, in particular, is of global importance. A co-founder of African cinema, he is well known for his writing, filmmaking and activism against colonial and postcolonial violence and his critique of the inefficacies of the postcolonial state. His films, along with those of Djibril Diop Mambéty and other Senegalese filmmakers, are important documents filled with clear and insightful social criticism. Senegal has also produced many important writers, including Aminata Sow Fall, Ken Bugul, Boubacar Boris Diop, Abasse Ndione and Fatou Diome, and literary works such as Cheikh Hamidou Kane’s Ambiguous Adventure (1961) and Mariama Bâ’s So Long A Letter (1981)

.

Sy’s artistic philosophy has always been rooted in the desire to liberate the Senegalese people from colonial violence, and his work brings history and politics into the postcolonial context.

Together with these many artists and thinkers, El Hadji Sy has voiced the experiences and concerns of a people whose alienation far from ended with independence. These important figures have been crucial in conceptualizing Senegal — and the world — after the colonial period. In varied and individualized ways, their works trace an archive of cultural production in the context of Senegal’s postcolonial transition. Their artistic practices have established a paradoxical and strategic dialogue, often oblique and ironic, at times complicit, with competing aesthetic, historical, and philosophical narratives of Senegalese modernism (e.g., négritude and africanité). The following situates Sy’s work in a dialogical relationship with this ideological and epistemological context, to then consider his material practices and how they have contributed to shape his own artistic legacy as a major archivist of the city of Dakar.

Prefacing Sy: Dakar at the Confluence of African Modernity [1]

The Postcolonial Context

Dakar is an important city for deeply historical reasons; reasons that have everything to do with the complexities of African modernity. Across from the city itself is a valuable site of memory: the Island of Gorée, a place inscribed with the history of slavery. This site reminds us that Senegal is a former French colony. This fact is essential for two primary reasons: First, it reminds us that the core ideals underlying Western modernity were founded upon a legalization of the idea of the African subject as a slave, or an object. Second, and even more importantly, that the concepts of Africa and of Africans were created at the inception of Western modernity itself. In other words, from the moment of its conception Western modernity has always included Africa at its very core. As such, not only must African modernity take Western grand narratives into account when understanding its formation, but, even further, we must remember that the idea of Africa is at the core of Western modernity itself.

Jamaican-born cultural theorist Stuart Hall has described this as the powerful dance of desire between the colonizer and the colonized. It is not simply that the colonized requires the recognition of the colonizer, his master; the colonizer also requires the colonized subject’s recognition in order to achieve his being. It is not only the African who must take the “West” and its key hegemonic mythologies, its grand narratives, into account; the “West” and its hegemonic mythologies require the stable, contained concept of Africa to function within its narratives in order for Western modernity to achieve its being. History is categorical: it takes two to tango, and Dakar, as a modern city, precisely emerged out of the choreographed encounter between unequal partners.

The epistemology of Africa – and as such, the constitution of Africa – has been determined in many ways by great historical tragedies that continue to inform African nations today. African “modernity,” as such, cannot possibly be articulated without an analysis of how these previous events created strong, transnational and trans-historical institutions that perpetuated forms of oppression after the demise of colonialism and slavery. These trans-historical institutions constitute the core of Western modernity and play a part in the formation of contemporary African subjects. The modern African subject faces a particular “interpellation” into these discourses of Western modernity, whether they choose to or not – their subjectivity has been formed by these events, whose reverberations continue to shape the entirety of the globe today. An understanding of African modernity demands an exploration of how these fundamental events shaped it. For these events, as Congolese philosopher Valentin Yves Mudimbe tells us, constitute the core of the “colonial library” (our collective archive of Africa) to which Africans must return in order to re-determine their subject positions for themselves, and thus better see and understand their conditions.

When discussing his training and his artistic practices, Sy’s resistance to and escape from a Western vision of painting as well as the pitfalls of prescribed négritude are obvious. Yet, although he was critical of Senghor in many respects, Sy’s art entertains a form of dialogue (paradoxical and oblique, but dialogue nonetheless) with the paths created by Senghor.

Sy’s artistic philosophy has always been rooted in the desire to liberate the Senegalese people from colonial violence, and his work brings history and politics into the postcolonial context, formulating a new mode of discourse by joining active emotional involvement through personal narratives with a detailed historiographical, archival approach. Indeed, as a modern African subject, he understands that his modernity has been complicated by international grids of historical oppression and subjugation, and he acknowledges that these grids of oppression and subjugation have come to form the power structures that have compelled him to become both a creator and an activist.

The Senegalese Context

In addition to this broader context, the contours of postcolonial Dakar as a physical site and an ideological territory have been shaped and reshaped by the confrontation between the Senghorian era and its centrifugal, pan-African belief that “culture is at the beginning and the end of development,” and the centripetal, nationalist vision of the Diouf government that succeeded it. [1] For Senghor, Senegalese modernity was grounded in africanité, or the sum total of cultural values that are “common to all Africans and permanent at the same time”. [2] As he articulated in the 1960s, Senghor firmly believed in a pan-Africanism supported by more than the colonial past and the anti-colonialism of the newly independent African nations. For Senghor, “the cultural foundations of [their] common destiny” offered Africans a more solid basis for unity. [3] If africanité combined both the values of arabité and négritude, that is the values pertaining to Arab cultures and Negro-African cultures, nations south of the Sahara were largely associated with négritude. Senghor emerged as one of the most important proponents of négritude, an Afro-European literary and cultural phenomenon of the early twentieth century, which first articulated notions of “blackness” as a way of conceiving of a subjectivity that could transcend the deep divisions between Arabs, West Indian Africans, continental Africans and other members of the Black Diaspora. Internationally, it allowed them to come together and find a new form of self-respect. For Black Africans, négritude was also meant as an alternative form of self-knowledge than that imposed by dominant Western discourses:

Négritude is the whole complex of civilized values – cultural, economic, social and political – which characterize the black peoples, or more precisely, the black-African world. All these values are essentially informed by intuitive reason. Because this sentient reason, the reason which comes to grips, expresses itself emotionally, through that self-surrender, that coalescence of subject and object; through myths, by which I mean archetypal images of the Collective Soul; above all, through primordial rhythms, synchronized with those of the cosmos. In other words, the sense of communion, the gift of myth-making, the gift of rhythm, such are the essential elements of Négritude, which you will find indelibly stamped on all the works and activities of the black man. [4]

In the Senegalese arts of the Senghor era (and beyond), négritude’s radical (if essentialist) thrust translated into a prescribed recovery of, and emphasis on, elements (sounds, colors, forms, rhythms, etc.) that signaled the specificity of Black people and their contribution to human culture. This is precisely the context in which El Hadji Sy received his training and the tenets against which he directed the bulk of his “unlearning” energies throughout his artistic career. [5] Painting had not traditionally been a prominent form of art in Senegal until it was “introduced” by Senghor, via the École de Dakar, where Sy was educated. The school, as Philippe Pirotte notes, “allied painting, sculpture and crafts to the literary movement and ideology of négritude” and it was “an attempt to assert a distinctively ‘African’ voice in the arts, free of, if borrowing elements from, the traditions of colonial nations.” [6] Through the École de Dakar and Dakar’s hosting of the Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres (World Festival of Black Arts) in 1966 Senghor sought to establish Dakar as an emergent art center, based on an aesthetic characterized by recognizable pan-African motifs and materialized through the pursuit of an “instinctive” africanité. This significantly shaped Dakar’s emergent reputation and output as the Mecca of Sub-Saharan arts. [7]

When discussing his training and his artistic practices, Sy’s resistance to and escape from a Western vision of painting as well as the pitfalls of prescribed négritude are obvious. Yet, although he was critical of Senghor in many respects, Sy’s art entertains a form of dialogue (paradoxical and oblique, but dialogue nonetheless) with the paths created by Senghor. For, like Senghor, his work shows how the postcolonial condition manifests itself through culture, as well as how culture determines subjectivity. Even more, as an international, pan-African and Afro-European-American movement, Senghor’s articulation of négritude provided Sy many possibilities to think about creativity in the face of established artistic traditions, history, and race within and beyond the borders of the Senegalese nation.

When Senghor resigned in 1980, Abdou Diouf (who had been Prime Minister under him) became president (after the 1983 elections). Diouf not only distanced himself from the ideals of négritude and africanité, he created a program called Le sursaut national (The National Step Forward) which resulted in the increased institutionalization of “Dakar as a city of culture.” [8] Cultural politics under the Diouf government are known to have promoted technocratic expertise and the private sector to the detriment of less institutionalized, less “mainstream,” and looser public arts producing structures. For instance, at the same time as it neglected to finance cultural activities, stopped subsidies for artists based in “grassroots movements,” evicted artists from the first Village des Arts (a space for autonomous artistic creation founded by Sy and his colleagues), and transformed the Musée Dynamique (a key site of the 1966 Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres) into the Supreme Court, the Diouf government founded a range of new art institutions that articulated a Senegalese modernity rooted in “the plural traditions of the historical heritage of Senegalese societies.” [9] Among these institutions were ones that crucially consolidated the status of Dakar as the Sub-Saharan art hub, at the turn of the 21st century, including the National Gallery of Contemporary Art (1983) and Dak’Art, the Biennale of Contemporary African Art (1996, formerly the Biennale of Arts and Literature). It is against the backdrop of such a changing city that Sy’s art and activism has evolved.

His painterly practices can be seen as secreting Dakar, as generating an archive of the city of Dakar, sometimes quite directly, other times less so. With Sy, it would seem, all roads lead to Dakar…

It is indeed in Dakar that Sy has created some of his most important works—and been most strongly censured. For example, the first Village des Arts, which he created with other artists in the late 1970s, was a space of creativity, “a framework that provided the conditions for creation to take shape, not a structure that intervened or was orchestrated. Its existence was, at the very least, an achievement […]”. [10] Its forced eviction, on September 26, 1983 by the Senegalese state (under the Diouf government), was an important development in his work, for it marks a clear moment of contestation/protest for Senegalese artists vis-à-vis their status as creators in the city of Dakar, where they could no longer create freely. After his eviction, Sy became even more ambivalent towards the role of the state and state officials in art and cultural activism. His increased desire for complete creative and critical freedom and his “strategic interpellation of Senegalese cultural politics” were more strongly felt in his work and activism. [11]

Sy’s Modus Operandi: Secreting Dakar, Archiving Dakar

In a conversation with journalist and curator Julia Grosse, Sy speaks of his ability to adapt and transform: “Yes, yes. I can live anywhere, I don’t have a problem because I feel as if my creativity is within me. Leave me here for six months, give me freedom of movement and you’ll see what I can transform. I secrete things.” [12] This secreting, as Sy articulates it, is firmly grounded in the materiality of the spaces he inhabits and repurposes, including the objects he finds in them. And since Dakar has been the site where most of Sy’s secreting has taken place, much of his painterly practices can be seen as secreting Dakar, as generating an archive of the city of Dakar, sometimes quite directly, other times less so. With Sy, it would seem, all roads lead to Dakar…

A very concrete illustration of that, a trend that runs through Sy’s entire career, is his use of sacks of manufactured products such as rice, sugar, or coffee as canvases. One rationale for using such unconventional canvases is Sy’s interest in the mutability of matter: “I experiment with all sorts of different materials because I’m not interested in a discourse on materials but on how they change. From a restorer or conservator’s perspective, when works of art start to rot, they lose value. In fact, this aspect of transformation is essential.” [13] In addition to his embracing the transient and alterable materiality of the object, Sy’s paintings on utilitarian textiles, used to transport rice or sugar to and from Dakar, connect them to the global (neocolonial) capitalist system. His artistic practice repurposes the products of these global connections and is, in a palimpsest fashion, quite literally inscribed onto them, leading the spectator back to Dakar as the transit site for vital products of everyday consumption, for art, for both.

Dakar, as a city, is also an open, constantly mutating space in which Sy has mapped out his creativity and spread his artistic practices across diverse locations, from the museum into the street. In this respect, it is interesting to consider El Hadji Sy as an “observateur-participant” of Dakar’s life and artistic scene. This status, along with his cultural activism as part of collective initiatives such as the Village des Arts, has allowed him not only to chart space and time in Dakar but also to develop strategies to reach out to diverse sectors of its population. As Julia Grosse notes, Sy wants to be both inside and outside the museum: “Yes, it’s never just about one place. That’s why I am not too fond of the limited space of a gallery environment […] It wouldn’t be the way I work to just have a show that is inside the museum. There needs to be a connection to the people outside of the institution, who wouldn’t normally enter it”. [14] Sy’s desire to involve everyday people in his creation and exhibition process and his firm belief in the mobility of art has often been demonstrated. An excellent example of that is when he replaced a Dakar museum’s usual signage with three of his works, which he left hanging from flagpoles outside the building, for the entire duration of the exhibition.

Yet, one could certainly say that even when his art is “confined” within the space of the gallery, a major feature of Sy’s modus operandi is that he still manages to “stretch space” by repurposing materials and mobilizing the role of the spectator in the creation process. Indeed, the brilliance and creativity that characterizes Sy’s artistic work lies in his way of engaging the world, wherever he is, by transforming it. In a 2014 exhibition at the Weltkulturen Museum (Frankfurt, Germany), Sy worked with four stools from Papua New Guinea that were “ethnographic objects” from the museum’s Oceania collection (see picture “El Hadji Sy: test installation”). He mixed the artefacts with his own earlier works, placing them on Le Puits, painted that same year in Dakar’s Village des Arts, and next to Portrait du Président, also painted in Dakar in 2012. This mixing quite literally brings a part of Sy’s contemporary Dakar archive together with ancient objects from Papua New Guinea, stretching time as well as space. In Sy’s own words, the amalgam also implicates his very presence in the installation, altering the discursive context around the “ethnographic objects”:

I can displace these objects and establish a new contextual relationship with them, and a formal and philosophical dialogue with the practice of contemporary art. As an artist or an author, I am present, whereas the authors of the other objects are unknown. When the curators at the museum speak about them, they refer to this ancient object, which they are experts on and have written about. They can do this because the object has no author other than the ethnic community to which it is attributed. But when I am there with the object, then the curator is silent. They can no longer speak on behalf of the object because an author is there. So there’s a jump between the historical and contemporary practice. [15]

El Hadji Sy, Test installation Weltkulturen Labor, listopad 2014. Obraz na ścianie: Portrait du Président, 2012, akryl i smoła na papierze rzeźniczym, 190 x 200 cm; obraz na podłodze: Le Puits, 2014, akryl i smoła na jucie, 245 x 280 cm; kolekcja artysty; stołki: kolekcja Meinhard Schuster and Eike Haberland 1961, Papua New Guinea, drewno, Kolekcja Weltkulturen Museum. Fot: Wolfgang Günzel. Źródło: El Hadji Sy: Painting, Performance, Politics, pod red. Clémentine Deliss, Yvette Mutumba Diaphanes/Weltkulturen Museum, Zurych, Berlin 2015.

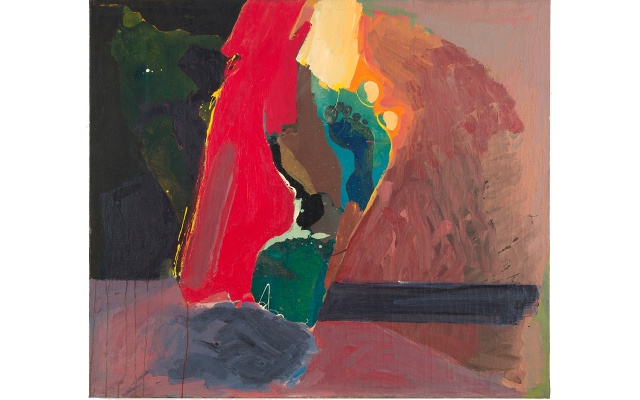

El Hadji Sy, No. 13 Esprit de l‘Univers, 1981, olej na płótnie, 95 x 111 cm, Kolekcja Kadist Art Foundation, Paris, Photo: Wolfgang Günzel. Źródło: El Hadji Sy: Painting, Performance, Politics, pod red. Clémentine Deliss, Yvette Mutumba Diaphanes/Weltkulturen Museum, Zurych, Berlin 2015.

While in this installation the centrality of embodied traces in the economy of the work’s composition is implied and more metaphorical than directly tangible, most of Sy’s painterly practices concretely bring attention to the materiality of the body. In the installation he created for the 31st São Paulo Biennale, Sy chose once again to create from repurposed materials “that bring along their own history.” [16] “I said I would participate under one condition, that I don’t transfer an object to Brazil. I needed to come, to visit the country, to meet, touch and share things with people […] I asked for coffee bags, because Brazil produces coffee. And then there is the sea, so I got nets from fishermen…”. [17] In addition, Sy reproduced the shape of human bodies by using ropes, focusing the installation around embodied traces filling the ocean: “We don’t know what is in the sea. But in the course of five centuries, over 30 million slaves were deported from west to east. One out of ten survived. The nine others are in the water.” [18] With today’s clandestine migrants (Africans and others) “new bodies fill the ocean, but there are ancient bodies there too.” [19] The spatial disposition of the installation also meant that to observe it, the spectators had to be participants in it, as if swallowed up by the sea, while their own bodies became partially visible to the spectators situated on the outside of the installation. The piece was inaugurated with the labor of other bodies, with the sounds and rhythms of the bare stamped feet of dancers and their music-less choreography activating the installation. [20]

While the centrality of embodied traces in the “Archéologie marine” installation signals the labor of other bodies, it also reenacts Sy’s foot paintings, a major distinctive mark of his art, which he began in the 1970s as a form of resistance to the models proposed by the École de Dakar. Sy’s early works were indeed animated by the traces of his own body (see picture “Esprit de l’univers”):

The Western understanding of painting often revolves around the notion of the eye and the hand. I wanted to kick out this tradition like a football, with one violent gesture. I’d do it until I could see the trace of my action on the canvas, my imprint, like the one the police once used to identify people. At first I thought this was dancing. Then I realised that I wasn’t dancing but kicking. After that experience, kicking became an instrument within the general economy of composition. My foot became a brush with which to paint a systematisation of the trace of the body. [21]

Sy directly implicates bodily traces of performance, negating the Western notion of the body as content and not as source. His foot paintings are also “the testimony of a fight against oneself, against one’s education, and against the idea of decorative painting within its own tradition.” [22] With this early “gesture of anarchy” Sy tried to escape “aspects of the École de Dakar aesthetics and the echoes of geometric shapes that reflect TransAfrican ways of depicting rhythms and motions, using a violent and particularly personalized interpretation of gestural abstraction.” [23] Such a powerful grappling with and refutation of artistic traditions is all the more significant in the postcolonial context of a young nation where everything has yet to be built, from the ground up.

In sum, in El Hadji Sy’s work, we find references to historical and political motivations behind his artistic choices, most of which emerge from or bring us back to Dakar as a city at the confluence of African modernity. As the five examples examined in this section suggest, Sy’s modus operandi focuses our attention on 1) the historically grounded materials he uses, repurposes, and reconfigures, including the very materiality of space, 2) the centrality of embodied traces in his economy of composition, and 3) his implication of the spectator in the creation process. These trends are symbolically and concretely grounded in the dakarois universe that has nourished his art and that his art has, in turn, contributed to transform and regenerate. By secreting Dakar through his painterly practices, Sy generates an archive of the city of Dakar. In so doing, he goes against a trend that has long had devastating consequences on African art: the difficulty to materially preserve African art and the epistemological gaps that stem from such difficulty.

The Question of the Archive in Africa: Sy’s Material and Epistemological Remediations

The Archive and/of an Exceptional Legacy

Sy’s archiving of Dakar through his artistic practice put the city and himself on the map of contemporary international art. But it goes much further: it raises, and crucially so, the question of the archive in Africa, in both a material and an epistemological sense. In fact, Sy’s archiving of Dakar through his oeuvre contributes to remediate the problem posed by Valentin Yves Mudimbe through the notion of the “colonial library.” This dual remediation is crucial to understanding Sy’s peculiar legacy as an African artist and to envisioning an equally strong future for the continent’s booming art scene.

Let us first consider the material dimensions of the question. Sy is an artist of exceptional originality, whose work traces an archive of the postcolonial Dakar context that substantially contributed to bring it to life. Yes, indeed, but how? That is precisely the question. After his eviction by the state from the first Village des Arts, in 1983, Sy sought to safeguard his works from destruction and was able to do it by entrusting significant pieces to his German friend and patron Friedrich Axt. In 2010, Axt passed away and the collection was returned to Sy who has lent it and its accompanying archive to the Weltkulturen Museum, the Frankfurt-based museum of contemporary art with which Sy has entertained strong ties for more than thirty years.

This exceptional legacy includes early works in oil, tar, wax and acrylic from the 1970s and 1980s, such as the paintings produced by Sy with his naked feet in a riposte to the Senghorian official line, few of which have survived until today. Indeed, Sy made a point of sending key paintings to Germany, works that he felt represented a significant shift within his practice. Original newspaper cuttings, invitation cards, photographs and posters, all meticulously conserved by Axt, contextualize Sy’s oeuvre within the Senegalese art discourse of the time. An existing constellation of early paintings and accompanying materials such as this […] is rare to find for an artist of Sy’s generation whose practice has been predominantly based on the African continent. Even today, the dispersal of artworks, problems of climate and conservation, the passive state of museums of contemporary art, and the African continent have all made it difficult for a substantial body of works – and therefore a genealogy of art practice – from the post-Independence period in Africa to survive until today. [24]

It is crucial to articulate the possibility of this legacy in the light of the systemic factors that severely disfavored African art, especially before the global turn of 1989. At the time, few art institutions showed interest in purchasing, exhibiting or otherwise supporting contemporary African art. The art scene was almost exclusively monopolized by European and North American discourses and exchanges, and Africa had no representation in this traffic. Most African artists had little to no access to conservation facilities and could only sell their art to passersby (expatriates, tourists, casual art aficionados), who often provided the only channels of survival for the African continent’s contemporary artistic production. It is hard to even talk about preservation when most of the continent’s art served to enhance private, amateur collections. As Yvette Mutumba, research curator at the Weltkulturen Museum, indicates, this conjuncture “led to a wide dispersal of works by artists from the African continent and contributed to a fragmentation of the genealogy of artistic practice.” [25] It is in this context of massive dispersal and relative oblivion of contemporary African art that Sy was able to use channels of strategic exchange to secure the very material existence of his art. His success in archiving his substantial artistic legacy is already an utterly creative and political act. It was also an effort that did not take place along the lines of colonial dependencies between Senegal and France, between Dakar and Paris. It was, instead, established through a German collaborative network centered around the city of Frankfurt. In this light, Sy’s preservation gesture is all the more singular.

Another Kind of “Archival Impulse”

We could thus consider Sy an “archival artist,” an artist moved by an “archival impulse,” in a different way than that conceptualized by the American art critic and historian Hal Foster. “Archival artists,” Foster says, “seek to make historical information, often lost or displaced, physically present” by elaborating “on the found image, object, and text” and drawing from sources that are “familiar, drawn from the archives of mass culture, to ensure a legibility that can then be disturbed or detourné; but they can also be obscure, retrieved in a gesture of alternative knowledge or counter memory.” [26] What we have with Sy is not specifically an impulse to restore, recuperate, or recycle a mundane document to remediate its meaning in relation to a pre-existing archive. Sy’s détournement concerns not a pre-established meaning, but a meaning that simply would not exist, if it were not for this “archival impulse.” The impulse is not to re-mediate the archive by using new media channels or new technological supports. The impulse, in Sy’s case, is to remediate an archival gap, simply and squarely, to avoid becoming part of the non-archive. It is a gesture of alternative knowledge or counter memory, yes, but one that the archival artist launches against the prospect of effaced self-knowledge and the absence of memory. Sy’s archival impulse acted upon the same material disappearance and epistemological oblivion that has characterized the African continent since the colonial encounter.

His artistic practice repurposes the products of these global connections and is, in a palimpsest fashion, quite literally inscribed onto them, leading the spectator back to Dakar as the transit site for vital products of everyday consumption, for art, for both.

Sy’s impulse thus leads us to a second form of remediation: his epistemological remediation of the “colonial library.” As noted by Mutumba, Sy’s artistic practice and his ties to the German curatorial context can be seen as “a significant step towards the historical contextualization of contemporary art practice from Africa. [27] Sy’s archival impulse, rising to the restorative task of filling historiographical and epistemological gaps, opens up a universe of possibilities: “It has now become possible to present the tangible biographical trajectory of this outstanding artist [Sy] and his relationship to the institutional history of a European museum that took shape before the growing globalization of the art world in the 1990”. [28] We can then return to Sy’s work and better understand both its position within Dakar, as well as its complex interactions with international grids of power that have made him a creator and an activist, a Senegalese artist, and an artist of the world.

How archives shape the substance of our personal and collective memories, even as they locate visions of the past and project scenes of the future, cannot be overstated. By endeavoring to preserve his visualization of Dakar, as well as the continent of Africa, Sy interrogates the ways in which communities express and document their heritage and renewed identities through the vast array of tangible and intangible forms and formats that make up the archive. Not just a repository of records, the archive governs, as Foucault tells us in The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969) what can be uttered in the present. [29] Through Sy’s own archiving of Dakar, we can thus trace the genealogy of a city that has become the lung of African art on this planet. While Sy’s archival impulse has immediate individual consequences, its scope would not be fairly assessed if we did not acknowledge how much it contributes, at the same time, to reconciling the battling forces of the archive and the non-archive after colonialism, after Orientalism, and the many correlate “isms” that still shape our fraught relationship to African knowledge and memories.

As Mudimbe demonstrated, our collective archive of Africa (what he calls the “colonial library”) is forever marked by abysmal omissions, concealments, misrepresentations and appropriations. By submitting the world to its memory, the West forced its “colonial library” onto colonized people. This cumulated archive of knowledge on Africa is inevitably mobilized as soon as we talk about, write about, or think about Africa today. And, as Aimé Césaire’s famous Discourse on Colonialism (1955) made clear, no return is possible, only new beginnings. [30] We must therefore excavate and supplement the “colonial library” to anchor these new beginnings and rearticulate African epistemologies on Africa’s own terms. [31] This is precisely where Sy’s archival impulse garners full significance, bringing us closer to the possibility of increased self-knowledge for Africans.

Leveraging the “Elsewhere” of Contemporary Art

In conclusion, the pursuit of his archival impulse (and its material as well as epistemological ramifications) did allow El Hadji Sy to emerge as an outstanding contemporary artist and a major archivist of the city of Dakar. Yet, in our view, Sy’s exceptional legacy ultimately draws the contours of another important contribution: artists like Sy have had a decisive impact on the construction of an “elsewhere” in contemporary art, one that we consider to have encouraged truly global artistic exchanges. His enduring relationship with Friedrich Axt and the Frankfurt-based Weltkulturen Museum constitute but one example of what we mean by that. Sy was recently asked if it was more interesting for him “to tour [his] exhibition to Prague or Warsaw, for example, rather than to one of the usual art world venues in London, Paris or New York.” [32] His answer exposed the potential he sees in this “elsewhere”: “Of course, because I think there is a different idea about art from Africa in Prague and Warsaw. People don’t have so much information about it. In London, I’d receive a different critical response…” Emerging along global routes that largely bypass “the usual art world venues,” this “elsewhere” is carving direct art transits between cities in Africa, Central and Eastern Europe, South America, and so on, paving the way for future generations of artists (African, Polish, and others...) to consolidate and leverage the channels of an alternative, de-centralized globality. As Sy’s work and its international circulation showcase, the individual and collective benefits of these thriving collaborative networks have just begun to be reaped…

BIO

Frieda Ekotto is Chair of the Department of Afro-American and African Studies and Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Michigan. She holds a Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota. As an intellectual historian and philosopher with areas of expertise in 20th and 21st-century Anglophone and Francophone literature and in the cinema of West Africa and its diaspora, she concentrates on contemporary issues of law, race and LGBTQI issues. She is the recipient of numerous grants and awards, including a Ford Foundation seed grant, is the author of seven books and numerous articles in professional journals. In addition she has lectured at universities in several countries.

Mélissa Gélinas is a Ph.D. candidate in Comparative Literature at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, where she is also pursuing a Graduate Certificate in Screen Arts and Cultures. In her dissertation, she examines multilingualism and language ideologies in 21st century cinema and literature. Her research areas include film and media studies, literary studies, postcolonial theory, translation studies, and sociolinguistics.

*Cover photo: El Hadji Sy, No: 13 Espirit de l’univers, 1981. Oil on Canvas, 95 x 111 cm. Collection Kadist Art Foundation. Photo credits: Wolfgang Gunzel. Courtesy of Weltkulturen Museum, Frankfurt.

1. Mamadou Diouf, “El Hadji Sy and the Quest for a Post-Négritude Aesthetics.” El Hadji Sy: Painting, Performance, Politics, eds. Clémentine Deliss and Yvette Mutumba. (Zurich, Berlin: Diaphanes/Weltkulturen Museum, 2015), 135.

2. Diouf, “Quest for a Post-Négritude Aesthetics”, 166.

3. Ibid.

4. Reiland Rabaka, “Aimé Césaire and Léopold Senghor: Revolutionary Négritude and Radical New Negroes.” Africana Critical Theory, (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2009), [Senghor, quoted in Rabaka], 132.

5. Hans Belting, “El Hadji Sy in Conversation with Hans Belting.” El Hadji Sy: Painting, Performance, Politics, eds. Clémentine Deliss and Yvette Mutumba. (Zurich, Berlin: Diaphanes/Weltkulturen Museum, 2015), 300.

6. Philippe Pirotte, “Dancing in and out of painting.” El Hadji Sy: Painting, Performance, Politics. Eds. Clémentine Deliss and Yvette Mutumba, (Zurich, Berlin: Diaphanes/Weltkulturen Museum, 2015), 90.

7. Today’s Dakar is a globally recognized art hub. Held every two years, the Dak’Art Biennale is a major contemporary art exhibition. Dakar is also home to the IFAN Art Museum, one of the oldest in West Africa. A recent addition is the Raw Material Company, an artistic and intellectual space for creative African minds, which joins numerous galleries such as the second Village des Arts, a collective filled with the artistic energy of flourishing workshops.

8. Diouf, “Quest for a Post-Négritude Aesthetics”, 135.

9. Ibid.

10. “In 1977, he took charge of squatting an army barracks on the seafront of Dakar, which became the first rendition of the Village des Arts, a creative hub for seventy artists, actors, musicians, film-makers and writers. There, in 1980, he founded the multi-disciplinary project space Tenq, a Wolof term that signifies ‘articulation’, and continued to remodel this curatorial dialogue in other locations during the 1980s and 1990s. The international workshops that he organised under the same name in Saint-Louis du Senegal (1994) and Dakar (1996) enabled new networks to be forged between artists working in continental Africa and in Europe at a time when web-centric communications and social media did not yet exist. To do this, El Hadji Sy reclaimed a disused Chinese workers’ camp near Dakar’s airport and turned it into a second Village des Arts. The initiative was subsequently recognised by the Senegalese state and the studios still exist today, if with a somewhat milder agenda.” (Deliss 10)

11. Clémentine Deliss, “Introduction.” El Hadji Sy: Painting, Performance, Politics, eds. Clémentine Deliss and Yvette Mutumba, (Zurich, Berlin: Diaphanes/Weltkulturen Museum, 2015), 10. This “strategic interpellation of Senegalese cultural politics” connects him to Ousmane Sembène in fairly obvious ways (Deliss 10). These two artists are cultural activists who often challenge authority. Sembène, writer and father of African cinema, shaped a clear ideological agenda for his artistic production. He was concerned that colonized people, specifically the Senegalese, needed to be aware of their social conditions, oppressed by what Frantz Fanon called the colonial condition. First a writer, Sembène’s project was similar to Mudimbe’s in that he sought to free Africans from a perception and a memory of themselves forged by the colonial encounter and its devastating long-term epistemological consequences. But Sembène quickly turned to visual art because he wanted the Senegalese to see themselves on the screen as a way of understanding that they are alienated subjects, as a way of confronting their condition.

12. Julie Grosse, “El Hadji Sy in Conversation with Julia Grosse” El Hadji Sy: Painting, Performance, Politics. eds. Clémentine Deliss and Yvette Mutumba, (Zurich, Berlin: Diaphanes/Weltkulturen Museum, 2015), 45.

13. Grosse, “El Hadji Sy in Conversation with Julia Grosse”, 42.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid., 43.

16. Pirotte, “Dancing in and out of painting,”, 92.

17. Grosse, “El Hadji Sy in Conversation with Julia Grosse”, 46.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Pirotte, “Dancing in and out of painting”, 92.

21. Grosse, “El Hadji Sy in Conversation with Julia Grosse”, 45-46.

22. Pirotte, “Dancing in and out of painting”, 90.

23. Ibid.

24. Deliss, “Introduction”, 11.

25. Deliss, “Foreword”, 6.

26. Hal Foster, “An Archival Impulse” October 110.4 (2004), 4.

27. Deliss, “Foreword”, 6.

28. Ibid.

29. Michel Foucault, «L’a priori historique et l’archive» L’archéologie du savoir, (Paris : Gallimard, 1969), 165-173.

30. Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism. trans. Joan Pinkham, (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000), 45.

31. Valentin Yves Mudimbe, The Idea of Africa, (Bloomington, Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1994), xii.

32. Grosse, “El Hadji Sy in Conversation with Julia Grosse”, 45.