(A)pollonia, Transpolonia, Postpolonia, or New National Narratives

This text was previously published as an introduction; (A)pollonia. 21st Century Polish Drama and Texts for the Stage, ed. by Krystyna Duniec, Joanna Klass and Joanna Krakowska, Seagull Books, London – New York – Calcutta 2014.

This text is published with the permission and by courtesy of the authors.

Polonia was beautiful, proud, and unhappy. She suffered with sublime dignity. She demanded adulation and allowed her worshippers to die for her. Finally, she herself died. She couldn't handle the new circumstances in which, instead of consoling soldiers and inspiring poets, she had to take freaks, aliens, and outcasts under her wing; instead of uniting everyone under her banner, she had to learn to accept diversity; instead of telling beautiful stories, she finally had to learn the ones that had been forgotten and repressed. As a result, she grew ugly, got lost, sunk into depression and went away. She returned as (A)pollonia, Transpolonia, Postpolonia, Lack-of-Polonia, and, in many other guises, to tackle her own uncertain identity, past, and memory and face problems she had never even dreamed existed...

Polonia was the established historical narrative about Poland and a conceptualization of the Polish national identity, that was born and nurtured in subjugation. Polonia was a myth that had to be continually retold. A romantic and fin-de-siecle myth that, denying modernity, persisted as long as it could not be made material. This myth persisted under the partitions throughout the 19th century until 1918, when Poland briefly regained its statehood, and after World War II – when country’s sovereignty was limited by Communism and the Soviet Union.

Poland as Polonia was, therefore, a fantasy of national identity , and, as such, she was not a woman but an illusion, her relationships were all Platonic, and she knew nothing of real life. Only after regaining freedom and independence in 1989 did she (as (A)pollonia, Transpolonia, Postpolonia, etc.) acquire a body, and with it, the bitterness of heartbreak, the burden of unfulfilled expectations, and the onus of settling historical accounts and dilemmas of identity. Above all, she now had to contend with the real problems of real people and social groups, with local conflicts and global politics, with the standards of political correctness, and with postmodernist uncertainty. In short, she had to face the permanent crisis typical of the liquid modernity in which the societies of the West live.

Consequently, the readers of contemporary Polish plays and texts for the stage should not assume that, as one of Dorota Masłowska's characters says, "in Poland all you get is Poland."

1. In Poland – that is to say, everywhere

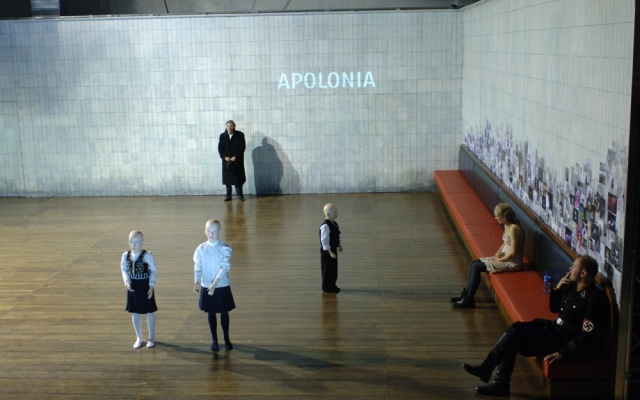

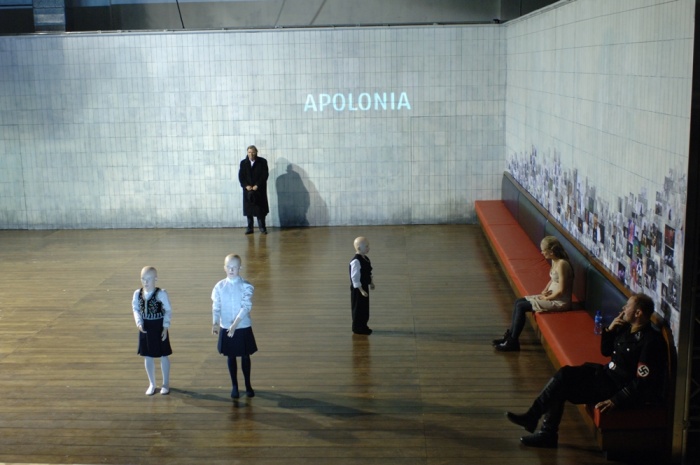

fot, (A)pollonia (2009), directed by Krzysztof Warlikowski,

Nowy Teatr, fot.Stefan Okołowicz

(A)pollonia directed by Krzysztof Warlikowski in 2009 sought to challenge the founding myth of Polish identity that had been preventing it from embracing modernity. Proof that the country has embarked on this road is found in the subject matter, conflicts, and dilemmas addressed by many plays and theatre productions in the Polish theatre of the last decade. The texts for the theatre written in the 21st century, while retaining a uniquely Polish flavor, take up some painful issues of the contemporary world and highlight the ethical and political aspects of historical narratives and constructs of identity. With their universal potential and political commitment, these texts will interest readers, appeal to stage directors and theatre-goers, and inspire academic discourse outside of the Polish context. In recent years, Polish literature and theatre have stopped dwelling on obscure topics peculiar to the local situation, but have joined a broader debate on global conflicts and dialogue between cultures. It even seems that, in many cases, these texts might bring to light matters that have so far been repressed or neglected, enhance public debate by setting out new dimensions of interpretation, and creatively transform our shared historical and cultural heritage.

It is directly related to the historical and political shift in Polish theatre which, at the beginning of the 21st century, began revisiting issues such as wartime trauma and postwar displacement, the Holocaust and anti-Semitism, the fall of Communism and the political transformation after 1989, and attempting to take stock of past complexes. Significantly, the language used to discuss these topics is modern and innovative, supra-national, and politically aware of gender and of post-colonial contexts.

There are more or less traditional stage plays, docu-dramas drawing on archival and documentary material, and texts for the theatre that use the found-footage method which compiles, adapts, and dramatizes many literary sources. All these texts form a polyphonic narrative about Poland as a symbolic site that, in "mixing memory and desire," brings into focus the transnational experience of the 20th century and the anxieties of the 21st.

This thematic arrangement covers the main chapters of Poland's history in the 20th century – from World War II and the Holocaust through the fall of Communism and the political transition after 1989 – and reflects the main directions in which contemporary art and public debate are developing as they take up the discourses of guilt and victimization, memory and oblivion, cultural changes, and economic exclusion. Many of contemporary plays address the four major themes on which Polish narratives of identity are based today. These are: the fate of the Jews (e.g. The Mayor; (A)pollonia); the war and its consequences (e. g. Transfer; Trash story; right, left, with heels); debunking national myths (e. g. Foreign Bodies; In Desert and Wilderness. After Sienkiewicz and Others; Small Narration); and life in a free market economy (e. g. No Matter How Hard We Tried; Diamonds Are Coal That Got Down to Business; I Love You No Matter What). These frames – Polin, Transpolonia, Postpolonia, Lack-of-Polonia – refer to Poland, although in a slightly different way. Each of them is a metaphor that needs to be explained.

Yet before we elucidate the titles and metaphors, we need to emphasize that, in using the word "Poland" so often, and in so many prefixed and modified variants, we are by no means waving the national flag, but actually trying to defuse nationalist rhetoric. The term "national" has become unwelcome today because of its exclusive, restrictive, and divisive aspect that can lead to symbolic oppression, confinement, and xenophobia. We want to open up the concept of national allegiance so that it becomes an invitation that allows for the invitation of hope. The texts we are referring to are pervaded by the possibly Utopian hope that other minds will find a home in the Polish cultural imaginarium and vice versa. Our aim is, on the one hand, to undertake an ironic game with jingoism, and, on the other hand, to shrug off the sense of uniqueness, and exceptionalism, try to subvert stereotypes, and give our own mentalities, and those of others, a good airing.

Poland, in all its guises, is not treated here as a fetish, but as a fluctuating mix of identities, experiences, and contexts. Alfred Jarry set Ubu Roi "in Poland – that is to say, nowhere" – we are telling stories that could take place "in Poland – that is to say, everywhere."

2. Curriculum Vitae

Any dialogue between cultures requires a degree of frankness. Polonia/(A)pollonia should say something about herself – a bit about what she's gone through, what she's guilty of, and what hurts her the most. What is it in her past that keeps coming back to her, causing nightmares and self-pity? Why does she have so much pride and so many complexes? Where does her prudishness and impeccably clean conscience come from? The answers to these questions are to be found in history, which is worth looking into if we are to understand certain motifs, threads, and symbols recurring in the plays and texts for the stage.

Where, then, does Polish megalomania come from? From recollections of the distant past when, according to one reckoning, she was the largest country in Europe. From the tolerance she practiced in the 16th century, when she was famed as "a state without stakes." From pride at one of the oldest parliamentary traditions in the world, the nobles' democracy that emerged in the 15th century, and the first constitution in Europe, adopted in 1791 just four years after the American Constitution.

Why the self-pity? Because of her cruel neighbors, who, at the end of the 18th century, divided Poland up among themselves, and kept her under their yoke for over 120 years. Because of the failed 19th-century uprisings against those partitioning powers. Because of her precarious position between Germany and Russia. Because her Western allies did not deliver on their promise to help Poland when Nazi Germany invaded the country starting World War II. Because of the indifference with which she was handed over to Stalin at the Yalta Conference. Because she feels that nobody in the world remembers that Poland was the first country to overthrow Communism, at a time when the Berlin Wall was still standing.

Why does Poland feel she is special? It is due to her Romantic poetry and her vision of Poland as the Christ of nations. Due to the Messianic ideals that inflamed the imagination of an enslaved nation. Due to having given birth to Nicholas Copernicus, John Paul II, and Lech Wałęsa...

Where did the unfailingly clean conscience come from? From a constant retelling of stories about the suffering she has endured, and denial of the pain she has inflicted. From glorifying her heroic deeds, performed in noble causes. From the number of Polish trees planted in Yad Vashem.

Whence the prudishness and conservative mores? From Catholic fundamentalism and everyday hypocrisy. From the cult of the Virgin Mary and devotion to the icon of Our Lady of Częstochowa. From petit-bourgeois hypocrisy and peasant fanaticism.

As the above indicates, Polonia/(A)pollonia constructs her identity on dubious premises, rehashed clichés, and rote-learning. This is aggravated by her complexes, the ones she acquired when living under Communism – poverty and a sense of backwardness – and the ones that emerged after 1989 – unemployment and social stratification.

She also has to grapple with the nightmares: images of the war, the massacre of Warsaw during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising, postwar deportations, Stalinist terror and the torture chambers of the secret police, and life in the Communist matrix. Then there is the sudden disappearance of her neighbors – the Jewish nation which had lived here for centuries – which haunts her with images of camps, but also of the pogroms and expulsions in which she was complicit.

If there is something that hurts Polonia/(A)pollonia, it is when foreigners refer to "Polish death camps," instead of “German death camps in occupied Poland” as Barack Obama inadvertently did in May, 2012 when posthumously awarding the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Jan Karski. Jan Karski was a courier and the emissary of the Polish Underground State, who during World War II tried unsuccessfully to bring the attention of the West, including President Roosevelt, to the plight of the Jews. The Presidential Medal was accepted on his behalf by Adam Daniel Rotfeld, a Polish diplomat and Holocaust survivor whose parents were killed by the Germans in 1943. The story is a good example of the historical paradoxes that shape public life and the image of Poland in the eyes of the West.

3. Polin

"Polin" means Poland in Yiddish and Hebrew. According to a Jewish legend, when Jews who in 1492 were fleeing Spain, Portugal, and the German states reached Poland, they read the country's name as "Po lin" ("stay here") and saw it as a good omen. For centuries, Jews coexisted in Poland alongside the Poles – retaining and cultivating their distinctness, and sometimes adopting the local language and customs. Whichever option they chose, the Jews were "at home" in Poland, though – as often happens among neighbors – this coexistence was not free of Polish-Jewish tensions and conflicts, often exploited by authorities pursuing a "divide and conquer" policy. The anti-Semitism of which Poles are often accused – even though their crimes against the Jews pale when compared to those of most other European nations – was not just the result of a reluctance to accept a different culture and religion, the urge to find a scapegoat in times of social unrest, nor of any psychological susceptibility to extreme ideology, but was also often motivated by political and economic factors, and was an easily exploited instrument in power-struggles as well as a way of channeling social frustrations. Nonetheless, Jewish culture became an inseparable part of Polish art and material culture. The Polish imagination has been shaped by characters from the literary canon such as Jankiel in Adam Mickiewicz's Pan Tadeusz (1834), Judyta in Juliusz Słowacki's Father Marek (1843), Doctor Szuman in Bolesław Prus's The Doll (1890), Meir Ezofowicz in Eliza Orzeszkowa's novel of the same name (1878), and Rachela in Stanisław Wyspiański's The Wedding (1901).

If Poles persisted in feeling blameless with regard to the Jews, it was owing to such literature, to the invaluable contribution Jewish intellectuals made to the scientific, cultural, and social life of the country, to a large Yiddish-speaking Jewish population of towns and cities in Poland before 1939, to a belief in Polish tradition of tolerance for other religions, as well as to a focus on their own national suffering. Even the Holocaust did not affect these attitudes for a long time, as Jewish people were understood as suffering the afflictions that befell the Polish nation at the hands of the Nazis and the Soviets as of 1939. Jewish victims were initially numbered among the Polish war dead, and once it was no longer possible to deny the exceptionality of Jewish fate, the prevailing narrative focused on Poles selflessly risking their lives to save the Jews, or on the condition of being helpless witnesses of the Holocaust. All the greater was the shock that greeted the publication of Jan Tomasz Gross' Neighbors (2000). Now the times of innocence are over.

To quote the eponymous Mayor from Małgorzata Sikorska-Miszczuk's play:

That's me from the Times of Innocence. Those times are over. The other me, the same me (after all, there's only one of me), is sitting in a chair with an outstretched hand, pointing at me. He's covered in wounds, he's all in pieces, hanging on by the skin of his skin, he won't talk much. All he can do is repeat, hand pointing at me: "It's me, it's me."

In 2000, Jan Tomasz Gross shook a hitherto-complacent public with Neighbors, his account of a previously little-known atrocity in Jedwabne – a small town in eastern Poland, where, in June, 1941, the Polish residents, instigated by the German occupier, brutally rounded up their Jewish neighbors in a barn and burned them alive. Gross's next books: Fear (2008), and Golden Harvest (2011) also concerned Polish persecution of the Jews in wartime, as well as the anti-Semitic outrages perpetrated just after the war. In the context of Polish Holocaust studies and numerous historical works on the subject, these books were by no means the only accounts of atrocities, but, owing to their (sometimes controversial) rhetorical edge and the author's talent for publicity, they reached a wide audience and shook public opinion. The atrocity in Jedwabne – emblematic of all other acts of Polish aggression against the Jews – posed a challenge to the nation's "clear conscience" and forced a reckoning with the question of blame at all levels of public debate.

Małgorzata Sikorska-Miszczuk has taken coping with this blame – its admission and denial – as the subject of her two-part play, The Mayor (2008-2011), inspired by the atrocity in Jedwabne, its coming to light, and the reactions of the town's present-day authorities and residents. The protagonist is based on the real-life mayor of Jedwabne, Krzysztof Godlewski, who valiantly faced up to the historical truth, and, in opposition to the wishes of his fellow townspeople, decided to speak of and commemorate the martyrdom of the Jews of Jedwabne. Sikorska-Miszczuk places the conflict stirred up by memories of a Polish crime against the Jews in the context of Polish mental clichés, such as the figure of the Penitent German – seen until then by the Poles (and by himself) as being uniquely responsible for what went on during the war – and by the Monument – an icon of Polish national megalomania:

The whole Radiant Figure glistens with gold, platinum, and pearls. Such is the purest stuff the Monument is cast of, as indestructible as our pride.

In (A)pollonia (2009), director Krzysztof Warlikowski undertook the deconstruction of historical and mental clichés from another perspective – that of sacrifice. By questioning the meaning of sacrifice as an ethical imperative, he not only struck a blow at Polish identity, but also provided a critical insight into the Christian and Mediterranean mythology in which it is rooted.

In (A)pollonia, setting the sacrifice of Iphigenia and Alcestis against the sacrifice of a Polish woman sheltering Jewish children at the cost of her own life reveals its morally ambiguous nature by making it relative instead of absolute. Ryfka was spared death thanks to Apollonia Machczyńska. Admetus was to be spared from death as long as he could find someone who would die in his place:

It’s hard to be someone's saviour. / He asked everyone. They all refused / All but one. / One silently said yes. Just that: Yes / His beloved wife said that, Alcestis...

Iphigenia says: "It’s a great honour for me to be able to save my homeland." Yet her death leads to others: her mother kills her father, to be killed in turn by her son. Just before his death. Agamemnon will quote the war-criminal narrator of Jonathan Littell's The Kindly Ones:

The only difference between the Jewish child gassed or shot and the German child burned alive in an air raid is one of method; both deaths were equally vain, neither of them shortened the war by so much as a second; but in both cases those who killed them believed it was just and necessary. Like most people I never asked to become a murderer… You can never say: I shall never kill. The most you can say is: I hope I shall never kill.

Violence blurs the outlines of intentions, motives, and attitudes: there is little difference between vengeance killing, offering a sacrifice, and plain murder, Warlikowski seems to be saying, when he invokes Apollo and Hercules, Greek heroes affected by or accused of the death of their loved ones. What's worse, killing oneself is also murder, and laying down one's life means acquiescing to violence and death. As the son of Apollonia Machczyńska, whom the Germans murdered for sheltering Jews, frantically asks: "Doesn’t a man have a right to save his own life?” Admetus, for whom his wife, Alcestis, laid down her life, addresses the audience:

You would not have agreed to such a sacrifice. / Someone sacrificing their life. Never. / You'd rather die. Would someone here prefer to die? You, sir? Madam? You wouldn't, sir? So that makes two of us: that's a relief. / Because all the rest love the lives of others more than their own. /We love our own life. And that's a sin!

Such risky juxtapositions and provocative questions serve to challenge the uncritically accepted dogma about the absolute value of laying down one's life for another. This not only demystifies the myth of sacrifice, but, above all, exposes the symbolic violence that underpins it. The revision of history accomplished in (A)pollonia is not just about the collateral suffering that sacrificing oneself for someone causes. Desacralizing sacrifice involves a revision of the paradigm on which Western culture – and, incidentally, Polish Messianism – are founded.

The discourse of guilt in The Mayor and the discourse of the victim in (A)pollonia are two ways of addressing the sense of loss prevailing ever since the Holocaust, especially in a country that witnessed it first-hand. Historically conditioned, rooted in myth and the collective unconscious, these two orders reflect the key tensions inherent in Western culture.

4. Transpolonia

In taking up the subject of relations with Germany, new Polish drama comes face to face with some of the most painful chapters of the nation's history: the long-term consequences of the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, which began World War II. The course of the war and its consequences determined the history of Europe until at least 1989. For Poland, the war was a pivotal event that turned it from a multinational state into an ethnically homogenous one, moved its borders westwards, deprived it of independence by placing it in the Soviet sphere of influence, and continued to affect the national mentality for decades as the new authorities perpetuated wartime psychosis, stirred up anti-German sentiment, and dwelt on the nation's martyrology while disregarding the sufferings of others. It was only after 1989 that it became possible to carry out a revision of entrenched narratives about the war, restore knowledge of facts that had been blotted out or corrupted by censorship, exercise independence in the assessment of political processes set in motion by the war, and show empathy towards her victims, regardless of their nationality. The spotlight was no longer on the strategies of generals, but on the fate of the civilian population; not on heroic deeds, but on acts of rape; not on military victories, but on postwar displacement. One could say that what occurred was a shift of focus in historical narrative from commemorating a collective tragedy to the recollection of individual ordeals – a shift from the national perspective to the human.

In the wake of the Yalta Conference, Poland lost its eastern provinces to the USSR, while gaining land in the west that had previously belonged to Germany. This launched a new age of migrations. Poles from Vilnius and Lvov were resettled in the cities of Wrocław and Szczecin, cities that had been abandoned by their previous German residents, who had been, themselves, forced to resettle. It was only recently – in a Poland free of political constraints and artificially-fuelled social anxieties – that one could take an interest in these former residents, and ask: who were the people who built these houses?

In that sense Jan Klata's 2005 production, Transfer!, based on a script by Dunja Funke and Sebastian Majewski, was a turning point in Polish theatre. It achieved a shift that was both historic and historical – by bringing to the stage a vivid historical subject after a long period of unwillingness to address history in general, by giving voice to witnesses who had until then been excluded from the historical narrative, and by providing a vehicle for stories repressed by the Polish collective memory. The cast consisted mostly of non-professional actors: real-life eyewitnesses to and participants in historical events. The contribution of the dramaturges was to take down their stories, edit and arrange them, and hand them back to their owners, the cast of Transfer!.

German men and women born before the war in what the Polish authorities would later call the Regained Territories spoke about their experiences during and after the war, which led to them becoming Expellees, to use a term later adopted in Germany. Old people told their life stories on stage: "[E]verybody had a copy of 'Mein Kampf' but nobody ever read it," recalled Hanne-Lore Pretzsch. Ilse Bode said that: "[W]e had a really loving father. But, unfortunately, he had to go off to the war. That's when all good things came to an end." "The women tried smearing soot on their faces, and putting on dirty long dresses, but it was no use. It was all the same to the Russians," was the way Hanne-Lore Pretzsch described the fate of German women at the hands of the victorious Red Army.

Parallel stories were told by Poles from the same generation from the East. "When the Germans came / the Ukrainians started killing people / I don't know why / it was horrible," reminisced Karolina Kozak. "I don't know whether I saw any Germans/ well, maybe one because I remember that he was nicely dressed / a belt saying: God Is with Us and he had elegant boots." Zygmunt Sobolewski added that "When they were coming back from the Eastern Front / the Germans weren't that elegant anymore / they would come to our house / grab some hay / pull off their shoes / then you could see the wounds, the blisters, the calluses, the frostbite." The Poles also recollected how, after being resettled to Wrocław from the East after 1945, they moved in to houses and apartments from which their German owners were being evicted: "a militia-man took me / to a three-room place on Grunwaldzka Street / but there were Germans still living there – / a woman with her daughter /ooof twenty / the militia-man says I'll be taking the apartment / and they will be resettled / I moved in."

A backdrop to these parallel and intertwining accounts of displacement was provided by the grotesque dialogue of actors playing the Big Three: Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt, who, at Yalta, made decisions about moving borders and nations on the map of Europe. This blending of the macro and micro perspective – the imperial and the individual, history and memory – helped to realign established thinking about right and wrong, and to reconsider the distinction into allies and enemies.

Wrocławski Teatr Współczesny, "Transfer!", reż. Jan Klata, fot. Bartłomiej Sowa

Wrocławski Teatr Współczesny, "Transfer!", reż. Jan Klata, fot. Bartłomiej Sowa

Wrocławski Teatr Współczesny, Transfer!, reż. Jan Klata, fot. Bartłomiej Sowa

Transfer! transformed Polish collective memory by forcing Poles to realize that others shared a similar fate, and that historical enemies were also victims of the same upheavals. It seriously shook up accepted historical thinking by replacing traditional Polish-German enmity with a Polish-German community of displacement. Without reapportioning the guilt, it introduced an element of empathy that undermined the discourse of authority. Empathy disarmed militaristic leanings and ideological prerogatives of the rulers by focusing on human tribulations instead of the raison d'etat.

Transfer! gave rise to a unique theatrical event, combining storytelling with stagecraft – the text has unquestionable literary merits – and successfully transferring documentary material onto a universal tale about existential entanglement in history.

This universality is even more apparent in Magda Fertacz's Trash Story (2008), which presents male stories from the front through the prism of women's experience. The women in question are: the ghost of Ursula, a German girl, whose father was killed on the Eastern Front, who was hanged by her mother so she wouldn't be raped by Red Army troops; the daughter of a concentration camp inmate, who spent her childhood in the shadow of his wartime trauma, and the widow of a veteran of the Iraq war. They all live in the house that once belonged to Ursula's family, who didn't manage to flee before the advancing Red Army.

The women's stories have a common denominator: they all testify to a life marked by masculine violence, and a loyalty towards the male narrative. All of them carry letters written by men in their hearts. A letter from Auschwitz: "My having survived is an act of terrible arrogance… I can’t write anymore. I no longer have an internal “no”… It's dead. I’m consumed with dread at the thought of the reality awaiting me just past the gate. There's no desire in me to face up to it…" A letter from Stalingrad: "We lie among corpses. The ground is too hard to dig graves. ... I am unmoved by anything; I kill on my left, I kill on my right—the more I kill, the faster this will end." A letter from Iraq: "The bomb that was supposed to blow our car apart went off a few seconds too early. A few seconds. My friends from another patrol weren’t so lucky. Bodies torn to shreds… If I come back without my legs, with scars all over my body, promise me that you’ll finish me off."

In Trash Story, the distant past provides a context for the suicide of the traumatized veteran of the war in Iraq. The play reveals how World War II is no longer just a point of reference for a peculiarly Polish narrative, but part of a broader reflection on violence as the driving force of history, where bearing witness to individual suffering is more important than settling scores.

Micro-history is also at the center of pilgrim/majewski's right, left, with heels (2008), which undertakes an ironic game with German guilt as the founding myth of what Tony Judt called "the postwar." The symbol of German guilt here are the shoes of Magda Goebbels, sentenced in 1946 by the "special section for degenerate objects" in Nuremberg to deportation to the East. As they change owners, they witness snippets of individual biography, changing mores, and the by-products of political conflicts. It is from such episodes that the historical narrative of postwar Polish history, marked as it is by the war and its consequences, is woven. In this narrative, the punishment of the shoes of Magda Goebbels has just come to an end, so it would seem that this stage in the settling of historical accounts is a thing of the past.

5. Postpolonia

The events of the year 1989 definitively overturned the postwar order established in Yalta. A turning point in the history of Poland and Europe alike, they sealed the fate of Communism, and ushered in political and economic transformations that led to profound changes in the collective and individual consciousness. Consequently, a need arose to take stock of the former system and settle accounts with the Communist authorities and their adherents. There was a concurrent need to validate existing constructs of identity: the hierarchy of values, cultural models, and attitudes in the face of the changes affecting the postmodern world, and the new challenges related to liberalism, post-colonialism and issues of gender.

The new situation called for reflection on the validity of a community founded on dreams of independence and the autonomy of the individual within that community, analyzing the national mentality in terms of postcolonial and gender theory, and, finally, coping with actual and metaphysical guilt with respect to the past. The point of reference for such a perspective were no longer specific historical events, but rather, a critical outlook on those events, transcending the mental legacy of the former era, and opening up to new possibilities, new values, and new contexts. Even though, in the spirit of Romantic myths, Polonia still occasionally celebrated herself as heroine and martyr, she was far more inclined to challenge this image by (post)modernizing her narratives of history and identity. And since, as remarked previously, Polonia gained a body after 1989, it is through the prism of the body that her metamorphosis needs to be presented.

By inscribing political transformation into the story of the sex change undergone by its hero/ine, Julia Holewińska's Foreign Bodies (2010) takes a look at the Polish revolution of the 1989 in the context of a struggle between the individual and the collective, and sees transformation as a painful process of regaining one's self outside of a disintegrating community. The play is based on the true story of a political dissident active in the underground movement after the imposition of martial law in 1981, jailed for his beliefs, who decided to undergo sex reassignment surgery after the country regained its independence in order to assert his/her own true identity that had been hidden until then. The heroine, who appears as the characters of Adam and Ewa, pays an enormous price for her decision: she is shunned by her nearest and dearest, humiliated in social situations, and cannot enjoy the privileges she would have almost certainly been entitled to under the new system if she had gone into politics as a man. In this situation, gender change becomes a metaphor of social transformation, by clashing the public with the private, collective versus individual freedom, and by confronting paradigms of masculinity and femininity. It turns out that, even in a free country, subjectivity, freedom and emancipation must still be fought for and continually negotiated. In the context of individual freedom, Julia Holewińska's play asks fundamental questions about community. After becoming Ewa, Adam asks:

Where are you now, friends of mine? Communism's dead, Adam's dying. Celebrate with me. Is that so hard? Do I sicken you? I won't change. Maybe just a bit, but you'll get used to it soon enough. Where are you? Why aren't you here? This is what we were fighting for. For freedom, tolerance, and the truth. This is my truth. Here I am. Give me your hand, I'm a little scared. I really need you now. A lot! Where are you? You're not here? That can't be. We swore before God and the crowned eagle banner that we'd always be together. For better or worse. Now you're not here. And me? Now I can finally be me.

Perhaps Adam/Ewa is really asking: what good is a self without a community? If Foreign Bodies is about negotiating one's own place within a collective, then In Desert and Wilderness. After Sienkiewicz and Others (2011) tries to deconstruct and question that community, and undermine the foundations of collective awareness.

The starting point of Weronika Szczawińska's and Bartosz Frąckowiak's text for the theatre is Poland's most popular young-adult novel, Henryk Sienkiewicz's In Desert and Wilderness (1912), which traces the adventures of two children, a Polish boy and an English girl, in Africa. By altering the story, adding new lines, and above all by encrusting the text with fragments of many other works of literature, philosophy and journalism, and entries from encyclopedias and reportage, the authors carry out a postcolonial critique of the colonial discourse underpinning classic adventure stories – present not only in Sienkiewicz's novel, but in all dreams of "the Polish empire, come alive" and in aspirations to "territory being taken for the glory of the fatherland". This critique employs such key categories as hybridity, orientalism, epistemic violence, mimicry, and the distinction into the center and peripheral territories. Its end-product is a found-footage text – an open dramatic structure, full of distortions and all sorts of interference, that radically deconstructs the colonial mentality of a nation that, though itself colonized, never renounced its imperial cravings and sense of supremacy over the Other:

Our forefathers told us that the Polish mind contains, and every now and then manifests, a dream of imperial existence. Perhaps now is the time to discuss whether we want to be an empire or not. And if we don't, what do we want to be?

"And if we don't, what do we want to be?" – is the key question after 1989. In its colonial aspirations and dreams of glory, Polonia compensated for its subjugation and historical humiliation. Postpolonia renounces dreams of grandeur in its quest for modernity, but in the process of constructing its identity challenges other, hitherto indispensable components of that identity. "Not wanting" can therefore also apply to history, which had until now defined the collective awareness. In Small Narration (2010), Wojciech Ziemilski makes such an attempt to cut himself free from history:

It began when while telling the story you realized you don’t want this history. You don’t want World War 2, or WW1, or communism, or the fall of communism, you don’t want September 1, September 17, May 8, July 11, May 3, April 19, August 1, December 13, June 4. You don’t want the Holocaust, you don’t want the Ribentropp-Molotov treatise, you don’t want Solidarność, you don’t.

The attempt fails. There is no escaping history. In Small Narration, the author has to grapple with the personal and family trauma caused by the discovery that his grandfather, Wojciech Dzieduszycki, had been an informer for the secret police. To understand, overcome and recount that past, Ziemilski had to deal with his own distance towards history, confront it with family feelings, childhood memories, images inscribed in his memory. He juxtaposed these feelings and memories with press clippings and snippets of documents. The vetting of the past, in its familial, moral, political, administrative, and historical dimensions, became a source of individual self-knowledge. Ziemilski was forced to ask what happened to his private history once it became public, and once the public turned out to be private.

6. Lack-of-Polonia

Economic transformation, the transition from a centrally-planned to a free-market economy, entailed painful social consequences: unemployment and destitution, as well as the emergence of profound differences in the standard of living between those who found a place for themselves in the new realities and those who proved helpless in the face of it. This gave rise to frustration at the inability to satisfy newly-awoken consumer desires, and to complexes at not fitting in with the lifestyle promoted in the media. The vision of success, of becoming true Europeans, targets of advertising campaigns, clients of mutual funds, and "consuming consumers" proved unattainable for many.

The so-called "victims of transformation" are people who were told they were "not up to it," who have a "psychiatrist treat [them] for lack of social opportunities," read advertising brochures pulled out of a recycling bin, and shop at discount supermarkets for "Ye Olde Poultry Loin" made out of pork rinds and dishwashing liquid. They are the subjects of plays by Paweł Demirski and Dorota Masłowska, who see the changes after 1989 not in terms of historical success, but the failings of the everyday.

In Masłowska's No Matter How Hard We Tried (2008), these failings are manifest in the crisis of identity (caused to an equal degree by the ghosts of the past and by the tackiness of everyday life) and the commercializing of the public sphere. Free-market mechanisms prove an insufficient remedy for traumatized memory: supermarket price wars have not displaced the recollections of World War II. The deadlock caused by poverty, complexes and history can be broken only by denial: "We're no Poles, just normal folks!” Lack-of-Polonia therefore describes a state of mind marked equally by a longing for "normality," or some vision thereof, and by the stigma of the past.

In Paweł Demirski's Diamonds Are Coal That Got Down To Business (2008), the failure is related to the economic shock treatment, or austerity program, that boosted the Polish economy in the early '90s without paying heed to the social costs:

This house was no longer able to pay for itself

So my father did the math

And the neoliberal calculator

which was the only calculator he had told him

the house should be sold and that was that

and that the only therapy that would keep us alive

was shock therapy and mass layoffs too

The play, a paraphrase of Chekhov's Uncle Vanya, shows the incompatibility of neoliberal rhetoric, which encouraged people to take matters into their own hands ("cultivating diamonds") and embrace the spirit of free enterprise, with the material and social condition of people regarded as the victims of transformation. On the one hand, we have Chekhov's characters cast into the present-day capitalist Poland, who feel that "there's nothing anyone can do about poverty and social exclusion which is the cost you have to pay for transformation and our neo-liberal economy," and see the charater of Uncle Vanya as having "precisely this educational tenor”. On the other hand, in No Matter How Hard We Tried, we have the tenants of a cramped apartment in a pre-war Warsaw tenement, with its "ongoing failure to renovate the premises since the war ended, or thereabouts,” and which "still lacks the tidiness, dryness and spaciousness so fashionable of late." All of them live "teetering between panic and boredom," feckless, damaged, and bereft of hope.

If this sense is absent in Przemysław Wojcieszek's I Love You No Matter What (2005), it is because he does not approach the present as a vehicle for social satire, but in order to tell a sentimental story. The focal point here is not capitalist exploitation and lack of prospects for the future, not the working conditions of dishwashers in a fried-chicken joint, but the hope that love offers. Seeing as that love is between two lesbians, it shatters social conventions, becoming an instrument of social criticism that strikes at patriarchal habits, actively opposes violence, and overthrows the established system of values. "We'll start a little lesbian family. A tiny, subversive cell that will blow this fucked-up society to smithereens,” states one of the main characters.

When her macho brother comes back from tour of duty in Iraq and finds out his sister has a girlfriend, he bursts out: "You know, I spent the last six months of my life in a place where things were for real. Death was for real and life was for real. And now I come home and everything's make-believe! Two chicks planning a wedding and a wonderful life together. It's ridiculous, man! Would you die for her?" "Yes," Magda replies.

The whole subversive potential of love is brought out in Magda's closing monologue:

we are

lovers

let's do it on the tombs of kings, commanders of uprisings lost the day they began

let's do it on monuments to patriotic youth

who without hesitation laid down their lives at the command of a bunch of old men

while you and me were kissing in some corner

and we’re alive and well today while they're dead, and our conscience

is clear because we came to know the taste of love instead of waving the flag

This opting for life over the ghosts of the past, personal happiness over patriotic sentiment, and the individual present over collective memory gives rise to the hope of overcoming the crisis of identity: of no longer being torn between shame and pride at being Polish.

(2013)

Translated by Artur Zapałowski

BIO

Joanna Krakowska

Joanna Krakowska is a historian of contemporary theater, editor, publisher, translator, and essayist. She is an associate professor at the Institute of Art of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw and a deputy editor of “Dialog” magazine. Author of Mikołajska (2011) – a biography of an actress and political activist in Communist Poland and PRL. Przedstawienia (2016) – the history of Polish theater in the period of Communist rule, 1945-1989. Co-author of two books on contemporary theater and politics: Soc i Sex (2009) and Soc, Sex i Historia (2014). The co-editor of the English language anthology (A)pollonia. Twenty-First Century Polish Drama and Texts for the Stage (2014) and Platform. East European Performing Arts Companion (2016). She was a Fulbright Senior Scholar at the Graduate Center, CUNY in 2013-2014. As a member of theater collective she co-authored two theater pieces: Kantor Downtown (2015) and Pogarda (Contempt, 2016).

Krystyna Duniec

Krystyna Diuniec is a theater historian, essayist and Professor at the Theatre History and Theory Unit, Institute of Art, Polish Academy of Sciences. Author of Jan Kreczmar. Grał jakby uczył (2005); Ciało w teatrze. Perspektywa antropologiczna [The body in theatre. An anthropological perspective] (2012); co-author of Soc i sex. Diagnozy teatralne i nieteatralne (2009) i Soc, sex i historia (2014); editor of the volume Aktor. Niepewna tożsamość [The actor. An uncertain identity] (2011). Initiator and head of the Laboratory of New Theatre Practices at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities in Warsaw.