Picasso once said: ‘If you are inside an aquarium, you can’t see its beauty.’ So the aim of the Laboratoire was to go outside the aquarium, to see it from outside, from a new perspective, to analyze and criticize it. After that you can come back inside.

Małgorzata Ludwisiak: Some works of yours circulate around the notion of alchemy. On the other hand, you speak a lot about visual syntax. What do these two notions mean to you?

El Hadji Sy: Alchemy is the title of a series of my works and it refers to the five elements – water, fire, soil, air and sky – which are like the five steps of life, they make life possible in the universe. And visual syntax is something different. It has to do with analogical images opposed to digital images. If you realize that we live in a globalized world which produces 10 million digital images per day and that it’s impossible to absorb them or make any use of them, and then the next day they are gone, then you ask yourself the question: what do I need more images for? Digital images have no human touch, they standardize the world. And in the reverse – the images that come from the imagination have a certain rhythm; they are related to the energy that surrounds us. An artist is a mediator: he takes these images and translates them for different publics in order to create a new perception, a new understanding of reality. A picture then, with its new grammar, acts as a creator of new views. The mediation of the artist is about bringing new human relationships or changing the existing ones. Art is not about originality, it’s about sincerity.

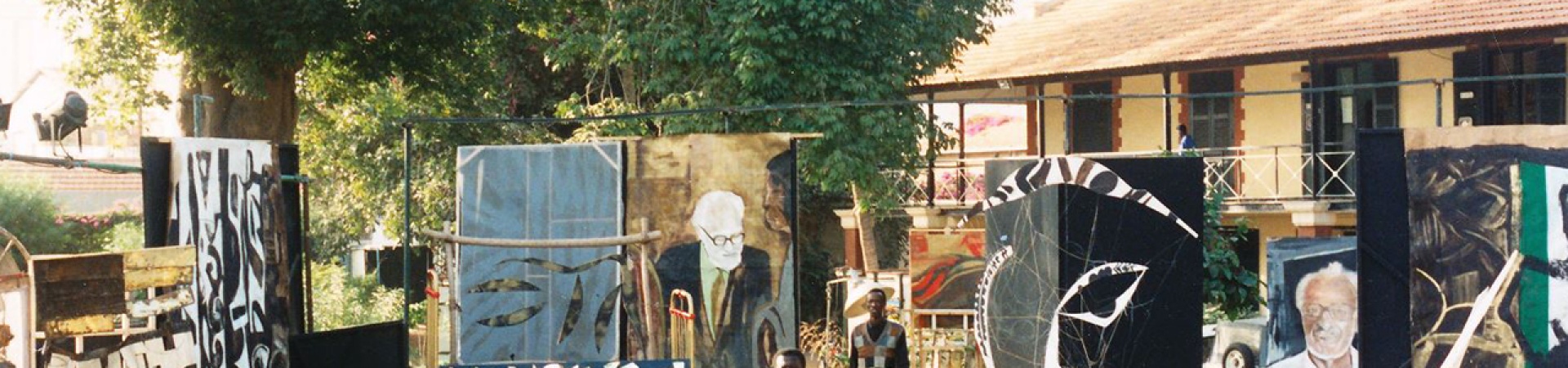

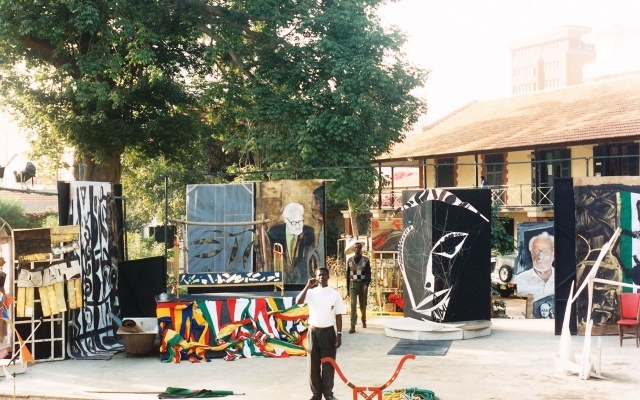

Przed pracownią El Sy w Village des Arts, Dakar, 2016, fot: Małgorzata Ludwisiak.

Przed pracownią El Sy w Village des Arts, Dakar, 2016, fot: Małgorzata Ludwisiak.

Przed pracownią El Sy w Village des Arts, Dakar, 2016, fot: Małgorzata Ludwisiak.

Przed pracownią El Sy w Village des Arts, Dakar, 2016, fot: Małgorzata Ludwisiak.

Przed pracownią El Sy w Village des Arts, Dakar, 2016, fot: Małgorzata Ludwisiak.

In the text El Hadji Sy and a quest for a post-negritude aesthetics, Prof. Mamadou Diouf describes you as a “rebellious” artist, a struggling one, trying to “shout out his anger” [1]. How much of yourself do you identify with such an attitude?

I’m certainly interested in pushing boundaries, which is always difficult if they are not physical. Take the boundary between Mauretania and Senegal: to some extent it doesn’t exist, as it was artificially created, it’s not real. But much more serious are the boundaries that are invented to make people feel secure. Security… I hate this word! An artist is never secure and he can never be secure if he really wants to be an artist! He should always stay outside of any boundaries, not be enclosed by them, but always remain open. The more open you are, the more you can relate yourself to the world. If you take the word “terrorist” and look up its etymology, you’ll notice that it means somebody who is defending the ground, terre. In his defensive position, he’s closed to a relationship with the world. That’s why you need a visual syntax – for creating a new ability to see things, to produce new actions, new positions!

So this is the way of “shouting out anger”?

It’s about showing disagreement or agreement. I can yell and I can remain silent. The worst position is the one you take if you close your eyes, ignore something which you don’t like. This is a position “in between”, a very secure one. When you are attacked by those millions of images coming from the media every day, they make you somehow unconscious, or rather not-conscious; they make you close your eyes. And the artist is someone who has to remain with his eyes wide open, he has to agree or disagree. He is like a sensor for the community and for that he sometimes has to be destructive in order to be constructive. That’s why painting for me is a form of activism. To some extent it’s pretending to save the world from sinking.

A kind of political activism?

In a broader sense. If you look closely, you’ll see that all the “isms” are dying or will die soon: capitalism, Islamism, communism… What is coming is “tics”: informatics, robotics… The world of digital images is a new battle field. In a certain sense, my project is not a political project. I never wanted to be a member of anything; I never belonged to any political party. On the one hand, I want to watch what the state or the city produces. On the other hand, I receive energy from society. I’m a mediator. I’m in a process of projection from now into the future.

But still, your decision to become an artist was already kind of your first fight, first “political” gesture…

Yes, I come from a family of intelligence – the Senegalese middle class. My grandfather created a coranique university in Saint-Louis in the beginning of the 20th century and he taught there. My father was a clerk, my uncle – a minister of security, my brothers are lawyers, architects, and teachers. My father wanted me to join the military! So when I announced my decision to go to an art school, it was a real fight in my life, with all the consequences. My parents refused to give me any financial support. I didn’t get any scholarships either, as I came from too wealthy of a family. So I started to design decorations for hotels, airports, hospitals as well as designing t-shirts. I earned some money to live this way. After I graduated, I never wanted to accept any grant from the state, in order to stay free, independent of any pressure from the system. I also didn’t want to teach in the art academy.

I wanted to ask also about two people who seem to be important to you: Prof. Cheikh Anta Diop and President Léopold Sédar Senghor. They presented two different ideological positions towards the understanding of “africanity” and the idea of modern Senegal.

I considered Diop, with his ideas of “africanity”, a kind of icon for the whole continent. I even met him several times. Sénghor was a product of France and I must admit, I had to fight against his ideas many times. We became friends only after he left politics and was no longer president. I must say I feel much closer to Diop. If you remember the figure of mummy, which was an important part of Laboratoire’s perfomances, this is the idea of the Afronaut, which comes from Diop. Now we have passed from the Afronaut to the age of robotics.

Now I would like to ask you about the performative and transdisciplinary roots as well as environment of your painting. I feel there is some link to poetry in it – is that right?

To some extent painting is poetry. Images can be rhythmic, melodic; they are like poetry. I read poetry a lot and I also write it. But I have never published any because I’m a painter, not a writer. I don’t want people to mistake me for a writer.

Your theater experience seems to be crucial for your attitude towards art and painting. When did it start?

It was in the early 70s when I started to go to the theater and to read French authors like [Antonin] Artaud or Roland Barthes, but also Brecht. I noticed then that theater offered society a kind of reversed mirror. But I must say that my first approach to theatre was through the body. In 1975 I started to design costumes for the National Theater in Dakar, changing the traditional way of thinking about a costume or decoration. I became interested in how the roles were changing thanks to the theatre. And how much objects like a chair or a table are actors, not only people. I was also impressed by the meaning of silence in the theatre – silence can be very strong and much more eloquent than a word. Today television with its constant noise and flow of images has killed the theater.

At the same time you started to work with the patients of a mental hospital.

Yes, it was because the relationship between art and therapy was very important for me from the beginning. I studied the art and writings of surrealists like André Breton or [Guillaume] Apollinaire, and I’ve learned a lot from them on the state of the human mind. Society thinks that people go crazy because they lose their conscience. I wanted to know what this conscience was. What I needed was not sur-realism, something which is “above” conscience, but I needed to look for a kind of under-realism. That’s why I organized an atelier with mentally ill people in a hospital in Dakar. You know, if you are crazy, you are sincere. These are the most sincere people in the world! They don’t have this double faculty of thinking one thing and saying the other. You also can’t pretend that you are crazy. I know because I tried it – but without success. So you can’t declare you are crazy and the same way you can’t declare you are an artist. In the hospital I’ve learned to be sincere.

How did the atelier work?

Well, in order to start it I went to meet the director, of course. After waiting for an hour or so, the door to his office opened. When I saw him, every single hair on my head stood up, because I saw the craziest man on the earth! After we talked, he said: ‘I like your project, come on Tuesday’. When I came, he assembled all the patients and said that I had to explain the project and see if they liked it. That was a moment of a real exercise – I had to convince all these people and get their acceptance. Then they started to tell me their stories, why they went crazy. In most cases, men became crazy because of women and vice versa: women because of men. And that’s how we started to work together – each week for a few months. They were making paintings, sculptures, and interventions in the hospital. In the beginning I was asking myself the question: “how can you transfer competence to someone who wasn’t waiting for it?” But crazy people are so sincere that they could receive it. It’s also because of the language of art itself, which is another kind of understanding; of communicating; of a love relationship.

Did it have anything to do with any interest of yours in psychoanalysis at that time?

I must say that I preferred Jung much more than Freud. One of his earlier books, Modern Man in Search of a Soul, was extremely inspirational for me, it really explained to me who I was. Because just after I graduated I was really questioning who I was. He introduced me to the writer Wilhelm Reich and his The Sexual Revolution. On the other hand, if you ask me about alchemy, you must remember it comes from Jung! It’s important to establish your personal link to the cosmos and to God.

The background of the radical group you belonged to – Laboratoire Agit’Art – was to some extent spiritual, is that right?

To join the Laboratoire, you had to present your work, which had to be spiritual and experimental at the same time. What also counted was its processuality. That’s why, after many years, Laboratoire ceased to exist – because you can’t institutionalize an experiment! The main goal of the group was to criticize. When I studied at the Academy, I never met a critical attitude there; for the professors everything was “nice.” And critique is something that puts you in a process, makes another discourse possible, giving you a stroboscopic view. And I’m speaking about another kind of critique than artistic critique. Once I used to paint red on red. Somebody criticized my painting in an “academic” way saying that it looked like blood. And I said that to me it was tomato! And that’s it.

One of the main figures of the Laboratoire Agit’Art performances was Georgi Plehanov, a founder of the social-democratic movement in Russia and a political dissident. Why did you decide to choose him?

Because he was protesting, agitating! Many artists, writers and thinkers were forbidden, censored or in jail during tsarist times. Recalling Plekhanov in the performance titles was a kind of homage to the social engagement. Picasso once said: ‘If you are inside an aquarium, you can’t see its beauty.’ So the aim of the Laboratoire was to go outside the aquarium, to see it from outside, from a new perspective, to analyze and criticize it. After that you can come back inside. Only this way can you change the inside situation. If you just stay inside, you just theorize. What’s important, is the process. And you can’t stop the dynamic of the process. It just exists – or you co-create it or it will throw you into the ocean.

The other art groups you co-created also had the goal to provoke social change.

Tenq, which means “a joint” in the Wolof [language], was a series of international workshops and a gallery. I wanted the artists to meet the public – that was the main goal. It started in 1980, when I transformed my studio in the first Village des Arts into a gallery space. It was the first gallery of contemporary art in Senegal! Of course there were some contemporary art initiatives in Senegal before, but they were organized by national institutes like the British Council or the French one which had their own goals. I had the idea of inviting artists for two weeks of intense residences in the Village des Arts and to end it up with multidisciplinary shows in open studios. There were no premises, no titles, no curatorial frame – the main idea was just working together.

And what about the group Huit Facettes?

It started in the 90s with the invitation of eight Senegalese artists to have an exhibition in Belgium. After that we decided to invite several Belgian artists, who made films or graphics, to come to Senegal and work together. We didn’t want the workshop to take place in Dakar, we went to the south of Senegal, to the village of Hamdallaye. They had a Belgian agriculture project there, banana plantations, etc. So there was a pre-existing infrastructure for agriculture, but completely no infrastructure for culture. What we did was organize workshops for local people, made films with them, taught them how to make batiks [the art of using wax and dye to decorate cloth –ed.]; we established a radio station there and the architecture for culture events with solar lights. The best thing is that the whole structure was built by artists and the Hamdallaye people there. It is still there today and serves the local community! The cultural, economic and social landscape of the village have also changed so that now the local people have learned how to make batik and the village is able to live off of it. Before they had to travel elsewhere to buy one, now people from other villages come to buy it in Hamdallaye. After that we did a workshop in Joal, where Senghor was born. Again we brought international artists to work with us and with the local people. Together we built a well, a canteen, and a structure for art residences. It is all still functioning today.

So you introduced a real change in the lives of this society!

Yes, and we did it together with them. It’s also important to remember that neither this group nor any other that I was involved in, has ever asked for governmental money. We wanted to be independent and we always raised the money ourselves. But never from the government. All these groups were involved in political activism, but it’s really sincere only when artists don’t help politicians, when they stay “insecure”.

And then the curators of documenta 11 in Kassel (2002) invited the group Huit Facettes to present the Hamdallaye project?

Actually, they wanted us to reconstruct the workshop of Hamdallaye a few years later. I didn’t like this idea, so I refused to go. Instead, I offered my place to one local artist from Hamdallaye who stood in for me. And he was so happy to go there; it was his first trip abroad! I went to Documenta 10 with Clémentine Deliss to present the Village des Arts, but in general I don’t like biennales or these kinds of events. I much more prefer to produce the structure and not be absorbed by it.

Do you still work together as a group?

Well, one of us has emigrated and another one has died… But we still call ourselves Huit Facettes – Eight Facets – although we are no longer a group of eight. If there is an opportunity, it could still happen that we would work together.

BIO

El Hadji Sy (born in 1954 in Dakar) - artist, painter, activist, curator, and one of the key figures of the West African art scene after its independence. He studied at the École nationale des Beaux-Arts in Dakar. Sy co-created such initiatives as Village des Artes, Laboratoire AGIT’ART, Tenq, and Huit Facettes. His works were exhibited in Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt, White Chapel Gallery in London, as well as the Biennale in São Paulo among others. In his practice Sy tests the field of art and possible ways of using art in various ways – he used radical theatre experiments, worked with local communities in Dakar, the Senegalese province and a mental hospital, and used painting as part of a performative, choreographic procedure.

Małgorzata Ludwisiak Director of Center for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle (since October 2014). Before used to work as a Deputy Director of the Muzeum Sztuki in Lodz (2008-2014), art critic, art historian, curator. Doctor of Philosophy, she graduated from University of Łódź (history of art), also studied philosophy. Member of AICA (polish section). Since 2001 until today, she publishes critical texts in polish art magazines inter alia in Obieg, Arteon, Exit and Kresy and in the exhibition catalogues. Co-curated (together with Jarosław Lubiak) a renowned exhibition Correspondences. Modern Art and Universalism in Muzeum Sztuki (2012–2013). She was a director of Łódź Biennale 2006 – second edition of the International Art Biennale – as well as a creator and director of Łódź Design 2007 – a first design and architecture festival in Poland. A curator of visual arts program and C.D.N. exhibition within the Festival of Dialogue of Four Cultures 2008. Member of AICA and CIMAM.

*Cover photo: El Hadji Sy, Plekhanov 7 / The Ashes of Pierre Lods [Les Cendres de Pierre Lods]. Performance. Théâtre de Verdure, Centre Culturel Français, Dakar 1990. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Weltkulturen Museum, Frankfurt

1. M. Diouf, El Hadji Sy and the quest for a post-négritude aesthetics, „El Hadji Sy. Painting, Performance, Politics”, red. C. Deliss, Y. Mutumba, Weltkulturen Museum, Frankfurt 2015, 13–140.