The right time, place and circumstances create extraordinary meetings. These can take place without unnecessary words or long-term consequences – two individuals attract each other like planets whose trajectories intersect for a moment in order to then continue revolving in their orbits. But the uniqueness of the phenomenon lies in the fact that these trajectories often prove surprisingly congruent. This was the metaphor that had occurred to me when El Hadji Sy [1] told me about his participation in the first Johannesburg Biennale in 1995 and the history of the purchase of one of his works (Man with a Bow) by one of his favorite rock stars – and at times also an actor, painter, art critic and collector – David Bowie.

I’m just an individual who doesn’t feel that I need to have somebody to qualify my work in any particular way. I’m working for me (David Bowie). [2]

The Joburg show was deeply symbolic, and it was also an example of using art as a political tool, a trend common for many post-colonial African countries. In hindsight, President Thabo Mbeki, Nelson Mandela’s successor, thought that the 1995 biennale marked the actual end of the apartheid era and thus the beginning of an ‘African enlightenment’. Bowie visited South Africa during a photo shoot featuring his wife, the model Iman Abdulmajid. In order to get to know the ‘rainbow nation’ better, the couple met with the term’s author – Nobel Prize laureate archbishop Desmond Tutu – as well as Nelson Mandela and the charismatic singer Miriam Makeba. In one interview, [3] Bowie describes his impressions from the biennale, noting the hypocrisy of the event’s ideological background. Art shouldn’t be for the elites only, and gallery and museum crowds should be as numerous as rock-concert audiences, he argues. Bowie calls the biennale ‘mind-jarringly moving’ in its freshness, but opposes the way honest intentions are exploited as a pretext for promoting a political idea, and a rather abstract one, after all, in a society with a very recent experience of racial strife and violence. The idea of the biennale is a political fantasy that can blur the works’ individuality, neutralize their power of influence.

Let me quote one more event from David Bowie’s life, an event that took place shortly after the interview above and which corresponds to another crucial theme present in the work of El Hadji Sy, here as an activist contesting fossilized discourses among experts, artists or politicians. Having launched his publishing project, 21 Publishing, Bowie suggested to writer William Boyd that he should write a book about a fictional unrecognized outsider artist. For the publication of Nat Tate: An American Artist 1928-1960, [4] Bowie staged a major reception (‘Nat Tate’ was named after London’s two most prominent galleries, the National Gallery and the Tate Gallery), precisely on April Fools’ Day 1998. The prank culminated in the sale of one of Nat Tate’s allegedly rare paintings in a Sotheby’s auction in 2011 for a mere £7,250.

The issue of lending meanings, values and contexts to objects that are mute and undefined in themselves is of crucial significance when we think of ‘traditional’ African art. [5] Mute, because they are detached from their original cultural context; for example, a mask without a dancer, his costume, the rhythm of the dance, and the community participating in the event would be meaningless to it. An ethnographic artefact becomes ‘authentic’ when certain characteristics defined by specialists (collectors, museum curators) are ‘bestowed’ on it. The notion of authenticity, like that of art itself, is of European origin. In traditional cultures, it was not the form of an object (mask, figure etc.) that was important, but rather its inherent meaning, its effect and function. The very word ‘art’ didn’t exist in El Hadji Sy’s native tongue, the Wolof language. Today the word tar is used, meaning simply ‘beauty’ (tar, it is worth noting, is a material El Sy often uses alternately with paints, experimenting with them like with alchemical components).

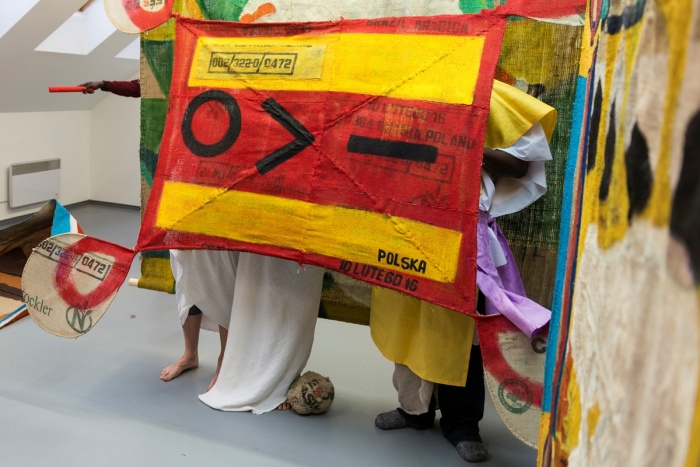

El Sy – like David Bowie did – often plays with artistic conventions and with fundamentally European classifications applied to African art. In an exhibition shown at the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt am Main, [6] he sought new contexts for artworks considered to be evidence of the craftsmanship of unknown artists rather than ethnographic objects; he referred to his intervention as ‘replacing the batteries’ in selected sculptures. In a performance created for the CCA Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw, the connection with the notion of authenticity and with African art is less direct and more complex, because rather than using existing museum items, the artist makes them himself. [7] Form – in this case an initiation costume used by young Senegalese boys – is ‘authentic’, that is, corresponds to the ethnographic reality. But meaning (that which really determines an object’s value in the eyes of its users) becomes ambivalent: the costume has been tailored by the artist and has never been used in an initiation ceremony, so it is not an ‘authentic’ item. After the performance, after being used by the artist, who has not only made the costume, but also ‘animates’ it, wearing it and thus creating a context for it, the tunic returns to a place meant for ethnographic artefacts (and shop displays!): draped on a mannequin. So is it a work of art? A product for sale? Or something that cuts across artificially defined categories?

The lack of a need to be judged, defined, inscribed in certain artistic trends or disciplines, to be imprisoned in terms originating in specific politico-cultural contexts, is evident on every level of the work of both El Sy and David Bowie. The former becomes a painter, performer, political activist and curator, and isn’t interested in being pigeonholed in compartments constructed for and associated with those activities. Despite holding Léopold Sédar Senghor, Senegal’s first president, a poet and friend, in high esteem, Sy refuses to join the ‘national art’ movement of the 1960s, which draws on native traditions, such as weaving, and rejects ‘colonial’ media such as painting. He also refuses to participate in seminal shows such as Magiciens de la terre (1989), [8] because, as he says, he isn’t a ‘shaman’ and doesn’t want to be perceived through the prism of a tradition that is not his own, nor to imitate historical processes by bringing artefacts from Africa to America, if that’s what accepting the invitation to participate in the São Paulo biennial would entail. [9] For the first ten years Sy refused to paint using a hand-held brush; he used his feet, trampling and dancing on the canvas, ‘kicking out’ the heritage of academic painting, drawing a map of his own trip. Significantly, he stopped painting with his feet when one of the paintings was acquired by the Senegalese government. Does this not bring to mind the game played with the art world by David Bowie / Nat Tate? The quest for such forms of practice and expression that wouldn’t fall within established categories and the making of objects that constitute a niche exempt from the yoke of definition is, in my opinion, the most intriguing aspect of the work of El Sy. [10] Or, perhaps more correctly, of the individual trajectory that is El Hadji Sy.

El Sy malujący baner podczas warsztatów w Weltkulturen Museum, Frankfurt, 2014. Zdjęcie: Wolfgang Güntzel.

El Sy na spotkaniu z Senegalczykami w Warszawie, Café Baobab, Warszawa, 2015. Zdjęcie: Karolina Marcinkowska.

„Autentycznie afrykańskie” tkaniny wax print na targu w Dżenne, Mali, 2008. Zdjęcie: Karolina Marcinkowska.

El Sy na przystanku – instalacji artystycznej przed Zamkiem Ujazdowskim, 2015. Zdjęcie: Karolina Marcinkowska.

El Sy vs. Zamek Ujazdowski, 2015. Zdjęcie: Karolina Marcinkowska.

El Sy na tle panoramy Warszawy, na dachu Instytutu Awangardy w Warszawie (Studio Edwarda Krasińskiego), 2015. Zdjęcie: Karolina Marcinkowska.

My name is El Hadji Sy, I’m coming from Senegal, [a] West African country ... where I live and work as an artist, curator [and] activiste politique ... the state I come from is a democratic country. We have elections and in Senegal we don’t recount the vote. We eat rice and fish. We paint, we dance, we articulate. That’s why I’m here. [11]

Significantly, in his first words to the audience of his exhibition at the National Gallery in Prague, El Hadji Sy ‘presents’ not himself or his artistic credo, but his country. [12] Let me also note the seemingly unimportant jingle preceding his statement; the short melody advertising the exhibition Painting – Perfomance – Politics [13] is probably meant to immediately bring to mind the African continent: it is a simple rhythm played on a drum. I am not trying to criticize the marketing strategy here of any particular institution (in fact, the concept of the Prague show also allowed African ‘traditional’ art too be highlighted, so the choice of drums may have been fitting). Nor do I want to bemoan the fact that artists from the ‘global South’ find it hard to define themselves – and thus to formulate their artistic creed – using purely artistic discourses, detached from their identity issues or the politics of their country of origin. It is, of course, entirely understandable that anyone visiting another country acknowledges their own strangeness. This may mean holding a different perspective on all kinds of issues (something that actually is desirable in art), or explaining – intentionally or not – the symbols, motifs and meanings of one’s culture. One can serve as an ambassador of one’s country (this is also how El Hadji Sy perceives his role) by presenting artworks, but also by virtue of one’s very presence.

But let us for a moment employ a strategy of reversal, [14] a very simple method of revealing the ethnocentrism (or, in this case, eurocentrism) of various staple terms and intellectual clichés. Let us imagine, for example, an outstanding French contemporary artist who, speaking at a press conference preceding the launch of his show in Poland or the Czech Republic, informs the public that France is a democratic country in Europe, that people there paint, dance and express themselves, and that their diet includes baguettes, soft cheeses and crêpe pancakes. Not to mention frog legs.

Not everything can be seen, but everything exists

– Senegalese proverb

Whether citing examples of one’s country’s culture or geopolitical self-definitions is an artist’s choice or a necessity, or even a constraint, whether such practices signify wealth or enslavement, one thing is certain: Africa as a continent is associated with a great many stereotypes. The designates of stereotypes – what we mean when we define something or ascribe certain characteristics to it – exist in a way, even if they can’t be seen anywhere in Africa. They exist in ideas, but also in newspaper headlines, in the language we use, in curatorial choices or marketing strategies. These constructs, though simplistic, inaccurate or purely fictitious, are frequently held to be true and are used and shared by people from diverse backgrounds.

Binyavanga Wainaina aptly described the phenomenon based on his own experience of being an African writer whose artistic freedom is constrained by expectations of ‘authenticity’. In his ironic essay How to Write about Africa, Wainaina offers straightforward advice on the subject:

Always use the word “Africa” or “Darkness” or “Safari” in your title. . . . Note that “People” means Africans who are not black, while “The People” means black Africans. . . . In your text, treat Africa as if it were one country. It is hot and dusty with rolling grasslands and huge herds of animals and tall, thin people who are starving. Or it is hot and steamy with very short people who eat primates. Don’t get bogged down with precise descriptions. . . . keep your descriptions romantic and evocative and unparticular. Make sure you show how Africans have music and rhythm deep in their souls, and eat things no other humans eat. . . . Taboo subjects: ordinary domestic scenes, love between Africans (unless a death is involved), references to African writers or intellectuals, mention of school-going children who are not suffering from yaws or Ebola fever or female genital mutilation. Throughout the book, adopt a sotto voice, in conspiracy with the reader, and a sad I-expected-so-much tone. . . . Readers will be put off if you don’t mention the light in Africa. And sunsets, the African sunset is a must. It is always big and red. There is always a big sky. Wide empty spaces and game are critical—Africa is the Land of Wide Empty Spaces. [15]

Stereotypes of Africa, in varying degrees of absurdity and generalization, are ubiquitous. Interestingly, sometimes it is the very users and heirs of the given tradition who repeat popular and often stereotypical interpretations of their own culture, whether to satisfy demand for a specific product or service (think of a ‘shaman’ catering to tourists in an ‘authentic village’ in, say, South Africa), to aid dialogue (e.g. by using words of European provenance, such as ‘trance’, ‘witch doctor’ or ‘fetish’, to describe far more complex phenomena), or simply out of ignorance. In this context, it is worth mentioning ethnographer Jacek Łapott’s research into the impact of tourism on the culture of the Dogon people in Mali. Łapott notes that the ‘number of “responsible people” in African cultures (not only among the Dogon) is shrinking; worse still, some defy the system by “switching sides” (becoming Dogons “otherwise”), e.g. by converting to Islam or “selling out” to the tourist industry with its profits’. [16] Thinking of the Dogons (one of the most stereotyped ethnic groups in Africa, like the Maasai, their cultural heritage frequently exploited as a kind of ‘brand’), one is inevitably reminded of a ‘social architecture’ project realized by Paweł Althamer and Youssuf Dara at the Bródno Sculpture Park in Warsaw in 2011. [17] Building an ‘authentic’ toguna – a ‘wooden structure with a thick roof . . . used as a meeting place for men’ – was probably just a reflection of Althamer’s (or both artists’?) fascination with the traditional culture of the ‘Dogon tribe, who believe in their cosmic origin’. [18] Leaving aside the many discussions surrounding Dogon cosmogony and the concept of ‘invented traditions’, [19] as well as the fact that the toguna ‘can also serve the prosaic purpose of a bus stop’, [20] the project still worryingly resembles the ‘primitive African villages’ staged at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900. Let us again reverse the situation and ask how the perception of the contemporary culture of, say, the Podhale highlanders would be shaped if one of them (dressed of course in the traditional folk costume consisting of a sheepskin waistcoat, a linen shirt, woolen trousers with side stripes, and kierpce leather shoes) were to build a copy of a Podhale shepherd’s hut in Dakar. ‘European Shepherd’s Hut Erected at the Arts Village in Dakar’ would obviously be the title of the newspaper article covering the event.

It seems that in the Polish context the term ‘Africa’ has similar connotations as those mentioned by the visitors to the ‘Dogon toguna’ at the Bródno Sculpture Park and those described by Wainaina in his essay. [21] What is perceived as ‘authentically’ African should be immutable (ahistorical, suspended in a void), traditional (eternal, ancient, with no traces of foreign influences – the so-called ‘ethnographic present’), ‘close to nature’ (whatever that means). Expectations will be similar with respect to fields as diverse as music, dance or culture in general, and it doesn’t matter that there are no such things as ‘African music’ or ‘African dance’, let alone ‘African culture’. Some Polish respondents even imagine an ‘African language’. ‘African art’ is generally associated with souvenir masks and elephant or giraffe figurines, or with collections gathering dust in the storerooms of ethnographic museums. It seems that multi-themed exhibitions, raising certain issues on a global scale, such as Year After Zero. Post-War Universalism and Geographies of Collaboration, [22] might introduce some sort of contextual thinking about how to read contemporary art in post-colonial countries. In Poland, however, they usually pass barely noticed, even among professionals, which is a pity. Was it the case with Year After Zero because it was focused on the ‘space between us’, on that which connects diverse threads and places at the same time (again the metaphor of planet trajectories comes to mind), rather than on a single theme or discipline? The stereotype of ‘African contemporary art’, however false, seems actually devoid of meaning in Poland today.

El Sy ‘plays’ with ways of seeing and interpreting the world, with the multiplicity of meanings and viewpoints, often so heavily influenced by where we come from.

The category of and the requirement to create ‘authentic African art’ even in the contemporary field has been the main theme of the artistic investigations of the British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare. [23] His paintings, photomontages and installations feature figures in Victorian costumes tailored with multi-color patterned ‘wax-print’ fabrics commonly associated with Africa. In reality, the production of wax-print textiles began in the Dutch East Indies (today Indonesia, home of the batik), where the technology was ‘stolen’ by the British, who found a market for it in West Africa. Significantly, in what brings to mind the background of some of El Sy’s works, Yinka Shonibare bought his first wax-print fabrics not in the Netherlands, Ghana or Nigeria, but at a street market in Brixton, south London (Brixton is, by the way, where David Bowie was born).

The theme of objects travelling, their transformations and the diverse meanings they acquire on the way, as well as the category of authenticity as applied to things made in Africa – whether ethnographic artefacts, contemporary works of art or objects that elude to such Eurocentric classifications – is often present in El Sy’s works. The artist himself says that ‘it’s not about being black, or making African art. I don’t know what African art is. We can’t put African art into a suitcase, and we don’t do that for European art either’. [24]

Returning to that which exists even though it can’t be seen, and to the complex issue of cultural stereotypes, we shouldn’t forget about the notions that El Hadji Sy arrived in Poland equipped with. In a video interview with Antje Majewski, the artist says: ‘I draw, and it’s what I carry inside me, it’s my own way of seeing the world’. [25] Throughout his Warsaw residency, [26] El Hadji Sy was keen to share what he knew about Poland, but also what he merely thought or had heard about it. Among the works created during the residency was a painting showing a figure resembling John Paul II kissing the Polish soil, but it may have been a traveler returning home or a praying Muslim. El Sy is aware that in the Polish context the motif will have clear connotations. To use his own words, he ‘plays’ with ways of seeing and interpreting the world, with the multiplicity of meanings and viewpoints, often so heavily influenced by where we come from.

For El Sy, Poland and the Czech Republic were Central Europe: a part of the world he had never visited. Western art curators told him that ‘nothing is happening’ in art in those countries, and that it didn’t make sense for him to show his works there because ‘they aren’t Paris’. That was precisely why El Sy thought it an attractive idea to go on a residency to Poland and become familiar with the country, its art and its people. Let’s not be afraid to say it: Poland was a kind of ‘dark continent’ to him. A distant, cold, unfamiliar, stereotyped, yet attractive notion. But also a deliberate choice to help spread knowledge about contemporary phenomena in Senegalese art, or even about African contemporary art in general. To highlight a different point of view, teach tolerance, fight racism through art. Significantly, El Sy’s residency in Warsaw coincided with Polish Independence Day and the nationalists’ annual march (passing, in fact, very close to the Ujazdowski Castle), and with the start of an intense debate about the refugee crisis. This means that El Sy’s postulate of promoting tolerance and openness through art and one’s own presence – even if hardly achievable with a single art exhibition – is legitimate and welcome.

Drzwi do nieskończoności na dziedzińcu CSW, 2016. Zdjęcie: Karolina Marcinkowska.

El Sy malujący Drzwi do nieskończoności, CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, 2016. Zdjęcie: Karolina Marcinkowska.

El Sy, performans Trzy klucze, z udziałem Małgorzaty Lisieckiej, Justyny Wencel i Mamadou Dioufa, CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

El Sy, performans Trzy klucze, z udziałem Małgorzaty Lisieckiej, Justyny Wencel i Mamadou Dioufa, CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

El Sy, performans Trzy klucze, z udziałem Małgorzaty Lisieckiej, Justyny Wencel i Mamadou Dioufa, CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

El Sy, performans Trzy klucze, z udziałem Małgorzaty Lisieckiej, Justyny Wencel i Mamadou Dioufa, CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

Tunika wykonana przez El Sy do performansu Trzy Klucze, CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

El Sy, Trzy klucze, detal, CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

I’m telling you, the finished object as such doesn’t interest me. It’s the process – that’s what fascinates me [27]

– El Hadji Sy

During his first visit to Warsaw, on 11 May 2015, [28] El Sy began his meeting with the public by apologizing for his poor English. He wouldn’t have been himself if he hadn’t added that Senegal used to be a French colony, that French is not the only language spoken there, and that he himself also speaks German and Italian. What was most important in that self-introduction was that it expressed an artistic creed that for El Sy is inextricably connected with language construed as a means of interpreting the world, sharing the resulting vision and communicating with others: ‘I have no particular message, I’m not a teacher, nor do I want to defend any ideology or anything like that . . . what interests me is how we can develop a new language, a visual language’. [29]

This new language is a method El Sy has termed ‘visual syntax’. Connections between what the artist feels, between the impressions flowing through him, and what appears on the canvas are transposed directly through the body to the picture. This is also a symbolic departure from the classic European notion of painting as something that requires certain technical skills and is primarily done with the hand and brush (compare El Sy’s use of feet instead of hands in his early period, as mentioned earlier). What appears in the painting occurs actually between the eye and the canvas and is an effect of visual impressions experienced by the artist ‘here and now’. During his Warsaw residency, El Sy stressed on numerous occasions that how he feels, what he feels about others at the given moment, what makes him sad or happy, will sooner or later ‘manifest’ itself in the form of a painting. For this reason he never plans the shape and character of his work – a key element of the ‘visual syntax’ method is to be simply open to what is happening and to the given context. One example of such an approach is the history of the making of Marine Archaeology at the São Paulo Biennial. The work was conceived during an air flight over the Atlantic, the concept crystallizing during street rallies and as a result of a meeting with a dance group. The materials used are fishing nets and coffee sacks, found by the artist upon his arrival and connected with the Brazilian context.

The place where the artist resides impacts significantly on the form or theme of his works. El Sy’s use of the common association of Poland with Catholicism and Pope John Paul II has already been mentioned. But an allusion to his specific situation in an urban space found a more literal expression in the second part of his Warsaw installation, featuring figures of football players. The artist drew here on his Brazilian experiences, but above all the piece was a reference to the nearby Legia Warszawa stadium, whose fans could be frequently seen (and heard) near the CCA. The theme was suggested by the place itself, and that created an interplay of meanings. Both religion and football are forms of cult, which means that they decisively shape the community’s culture and identity. In all parts of the world they stir up strong emotions, uniting people powerfully or dividing them. The question whether this power can replace language and be universally understood is one that El Sy leaves for us to answer. Following the cue offered by the location, he hints that the three elements of the Warsaw installation can be associated with three continents and their links: Europe, and Poland specifically, would be symbolized by the pope, South America by football, and Africa by the slave boat. This however is but one of the many possible interpretations of the work; the author himself endorses no particular way of reading it.

El Hadji Sy’s working method isn’t limited to visual syntax and being aware of a particular place or context, of returning objects and their changed meanings. It also relies fundamentally on the practice of ‘animating’ objects by inviting others, usually artists or members of the local community, to make art and perform artistic interventions. In this context, El Sy uses the neologism mise-en-espace, a modification of ‘mise-en-scène’. Sometimes, as in the case of the flying kites created for Youssou N’Dour’s Chimes of Freedom music video, this is mise-en-ciel, ‘placing-on-the-sky’, a celestial installation. Stagings in space are co-created by their recipients, whom El Hadji Sy seldom allows to remain just passive observers. His objects, paintings or large-scale installations (e.g. Marine Archaeology) force the viewer to occupy a specific position in space, to move, to use their body, to change positions, to reorient themselves in space. Meaning is created by the recipients in interaction with the work – every moment is unique and ephemeral here. The process that makes this interaction possible is far more important than the material artwork itself.

Translated from the Polish by Marcin Wawrzyńczak

BIO

Karolina Marcinkowska is an Anthropologist who holds a Ph.D. from the University of Warsaw, (her dissertation was based on her field research of the tromba possession cult in Madagascar). She is also the founder of the AFRICA REMIX project, is a cross-cultural communication trainer and anti-discrimination educator, and a coordinator of projects for NGOs. She was the Assistant Curator on the exhibition El Hadji Sy. At first I thought I was dancing and Public Spirit at the Center for Contemporary Art at the Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw. She has implemented educational and artistic projects in Ghana, Kenia, and Brazil, among others. She is affiliated with the Ethnology and Anthropology Institute at the University of Warsaw, the Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw (cultural studies) and to the Open University (lectures about contemporary African art).

*Cover photo: El Hadji Sy, detail from the work: Three Keys. Photo credit: Bartosz Górka. Copyright: CCA Zamek Ujazdowski

1. El Hadji Sy’s residency was part of the Artists in Residence (A-I-R Laboratory) residency program and took place from 2 October 2015 to 21 November 2015. During that time, I assisted the artist in preparing objects for a performance that would be the culmination of his stay, organized his visits to galleries, museums and the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, talked to him and listened to his stories.

2. See: http://www.brainyquote.com (accessed 3 April 2016).

3. A 1997 interview for the Times. For information about Bowie’s African links cf. Sean O’Toole, ‘Wearing Many Hats. Bowie in Africa’, 17 February 2016, online edition of Contemporary & (accessed 3 April 2016).

4. ‘David Bowie: How I exposed the pop star's fake artist, David Lister’, 15 January 2016, online edition of the Independent (accessed 3 April 2016).

5. More about the category of authenticity in: Shelly Errington, The Death of Authentic Primitive Art and Other Tales of Progress (University of California Press, 1998).

6. The exhibition El Hadji Sy: Painting, Performance, Politics was on show at the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt am Main from 5 March till 18 October 2015; more information on the Museum website (accessed 17 April 2016).

7. I accompanied El Sy on his visit to the storerooms of the State Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw. He was saddened to see unused, dead objects, mainly musical instruments and other practical devices, locked up in the basement, a fact that sheds light on the status of the object in his practice. According to El Sy, an artefact or artwork is created primarily to be used, to serve a purpose and convey a meaning. Moreover, it is always the work of a particular artist or artisan rather than – as in museum discourses – an example of the material culture of this or that ethnic group.

8. For more information about the controversial exhibition Magiciens de la terre, curated by Jean-Hubert Martin, which took place at the Centre Georges Pompidou and the Grande Halle de la Villete on 18 May – 14 August 1989, compare the show’s official website: http://magiciensdelaterre.fr (accessed 18 April 2016). The way African art is presented here resonates with one of two typical European discourses: art perceived as magic, an element of ritual. The other path of interpretation connects the nature of African objects to proto-Cubism, Expressionism or Surrealism, and stresses affinities between primitive art and European modernism. Cf. S. Kasfir, ‘African Art and Authenticity: a Text with a Shadow’, in: Reading the Contemporary. African Art from Theory to the Marketplace, eds. Olu Ogiube, Okwui Enwezor (London: MIT Press Ed edition, 1999).

9. More about the 31st São Paulo Biennial in 2014 on the event’s website (accessed 18 April 2016). El Sy created a work called Marine Archaeology, there one which reflected on the plight of all those (whether slaves or refugees) who had to leave their homeland. A Brazilian dance group was hired to add a new dimension to the installation.

10. The transformations of an individual who, due to their chosen trajectory but also to external factors (background, tradition), remains inscribed and ‘imprisoned’ in a particular discourse have been a key theme in the films of Djibril Diop Mambéty, a member of the interdisciplinary experimental artistic collective Laboratoire Agit’Art.

11. El Hadji Sy: Painting – Performance – Politics, 19 January 2016 (accessed 2 April 2016). A similar statement was made by El Hadji Sy during an open meeting from the ‘Common Affairs’ series, held on 11 May 2015 at the CCA Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw. Video documentation of the meeting: Translating the Present: Between Painting, Performance, Politics and Ethnographic Collection, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pFTToaZALK4 (accessed 2 April 2016).

12. The exhibition at the National Gallery in Prague, titled Painting – Performance – Politics (6 February – 22 May 2016), was one of the events staged to mark the Gallery’s 220th anniversary.

13. A similar situation occurred during a press conference presenting the Warsaw CCA’s exhibition plans for 2016. Due to the fact that El Hadji Sy was in residency at the CCA at the time, he was asked to announce his show.

14. Steven M. Leuthold discusses strategies of reversal as a means of exposing exoticising promotional strategies present in art, but also, for example, in tourism; cf. S. M. Leuthold, Cross-Cultural Issues in Art. Frames for Understanding (New York: Routledge, 2011), 19.

15. Binyavanga Wainaina, ‘How to Write about Africa’, Granta, no. 92, 2005, 40.

16. Jacek Łapott, ‘Wioska plemienia Dogon jako symbol ciała mitycznego przodka – czyli co zostało z mitu?’, Rytmy i kroki Afryki (Kraków: Wydawnictwo WAM Akademia Ignatianum, 2011), 58.

17. More about the toguna project at the Bródno Sculpture Park on the website of the Warsaw Museum of Modern Art (accessed 3 April 2016).

18. Wojciech Karpieszuk, ‘Afrykańska toguna stanęła w Parku Rzeźby na Bródnie’, 24 July 2011 (accessed 2 April 2016).

19. The concept of ‘invented traditions’ is from T. Ranger, ‘Invented Traditions in Colonial Africa’, in: The Invention of Tradition, eds. Eric Hobsbawm, Terence Ranger (Cambridge University Press, 1983). One of the many studies of Dogon ‘invented traditions’: ‘Dogon Restudied: A Field Evaluation of the Work of Marcel Griaule [and Comments and Replies]’, Walter E. A. van Beek, R. M. A. Bedaux, Suzanne Preston Blier, Jacky Bouju, Peter Ian Crawford, Mary Douglas, Paul Lane and Claude Meillassoux, Current Anthropology, vol. 32, no. 2 (April 1991), 139-167.

20. See: http://artmuseum.pl, op. cit.

21. Observations regarding Polish respondents’ stereotypical views of Africa are from the author’s experience as academic teacher and trainer. More on the subject in Katarzyna Kubin’s interview with Karolina Marcinkowska, Afryka bez maski: o spotkaniach z Afryką w nauce, w edukacji i w praktyce [Africa without a mask: on meetings with Africa in science, education and practice], http://ffrs.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/FRS_Seria-RoR_5.2015_Africa-Remix1.pdf (accessed 2 April 2016).

22. More about the exhibition, which took place at the Warsaw Museum of the Modern on 12 July – 23 August 2015, on the Museum’s website (accessed 2 April 2016).

23. What is ‘authentic’ African art?, BBC World News, 22 January 2016 (accessed 2 April 2016).

24. ‘El Hadji Sy in Conversation with Julia Grosse’, in: El Hadji Sy. Painting, Performance, Politics, eds. C. Deliss, Y. Mutumba (Frankfurt: Weltkulturen Museum, 2015), 44.

25. The Stone, the Ball, the Eyes. Conversation between El Hadji Sy and Antje Majewski, dir. Antje Majewski, video, 25’, Dakar, 2010, https://vimeo.com (accessed 2 April 2016).

26. As part of the presentation of works created during the Warsaw residency, El Sy invited CCA staff members and friends for a small-scale event – a performance that took place in his Ujazdowski Castle studio on 18 November 2016.

27. The Stone, the Ball, the Eyes..., op. cit.

28. El Hadji Sy was invited to the CCA Ujazdowski Castle as part of the series Common Affairs. A meeting with the artist, moderated by CCA director Małgorzata Ludwisiak, titled Translating the Present: Between Painting, Performance, Politics and Ethnographic Collection, took place on 11 May 2015. Video documentation of the meeting (accessed 2 April 2016).

29. See: http://www.csw.art.pl (accessed 2 April 2016).