The exhibition runs until 06/11/2022

AK: You have been researching Soros’ Centers for Contemporary Art for the last 16 years, is that correct? How did the journey start?

My journey began in 2006 as a journalist when I was editor of Flash Art International. I kept encountering references to this network of art centers that no one had ever spoken about in all of my educational experience. The more I looked the more of them there were and it became obvious as an opportunity to understand how contemporary art had an important missing history.

AK: How did you manage to get in touch with artists and curators involved in setting up the centers?

During that research trip I went to 10 cities and interviewed over 30 people. Only one was an SCCA director and the rest were mainly artists and next generation culture managers. After that research trip I put my focus on supporting artists from across Eastern Europe with my gallery in Berlin and my curatorial practice. When I began making The Influencing Machine in 2018 and setting up the archive, I just started cold-calling everyone affiliated with the Network. I’ve currently amassed the largest oral history archive connected to this story.

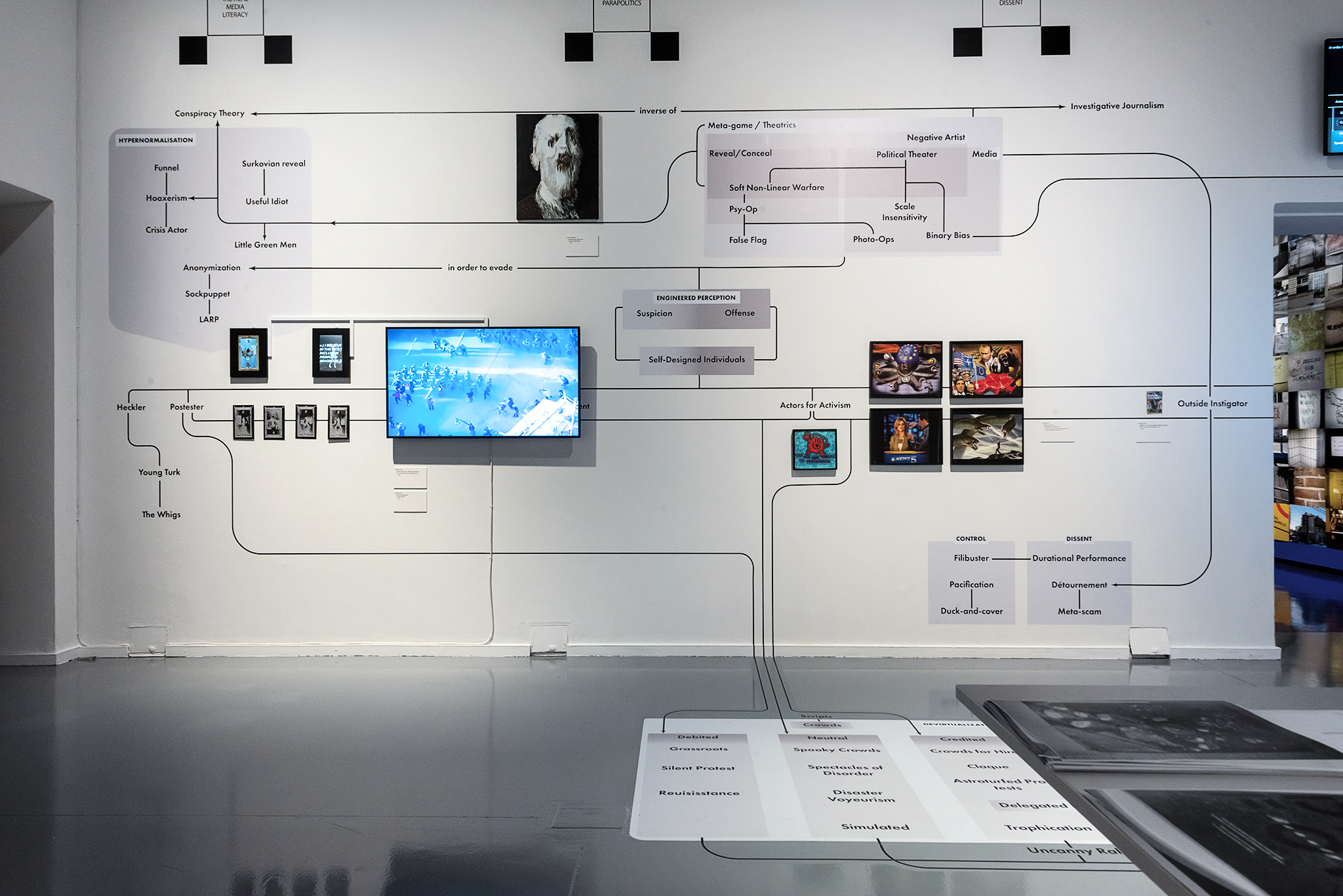

Maszyna wpływu w Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski. Fot. Daniel Czarnocki

AK: How did you approach those people? Where all of them open to working with you on this project?

I’m from the art world and have great credentials. I use that like a Trojan horse because I’m one of them and I know how to speak their language and know more about the period than anyone. Not everyone would take my call. Some refused to go on the record. With Everyone I’ve spoken to I am very forthcoming about my research regarding the origins of curatorial practice, socially engaged practice and tactical media. No one has ever disagreed with my thesis.

AK: You have combined artworks and documentation of exhibitions and happenings. How did you obtain those? Was it difficult?

Most of my interest is in the curatorial aspect of this story. Despite the insane amount of funding and production of art and exhibitions, there are not so many important artworks emerging from the good years of the Network. Just a handful are remembered. Mathematically that is hard to believe considering how prolific and well-funded this phenomenon was. My approach is to mix these particular frameworks and languages of curating, artmaking and storytelling.

AK: What was the methodology of building the archive?

I treated the creation of the SCCA Network Archive the same way they treated the creation of their artist archives. The archive binders profile each SCCA center showing any evolutions around mission statement, board and staff. But the nutritious moment of data lies in the ability to analyze the exhibition histories and how those concepts emerged and were developed. Once seen on a timeline you witness a clear moment of artificial emergent behavior and can see this advanced socially engaged practice emerging simultaneously across the network at an impossible rate of growth.

Maszyna wpływu w Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski. Fot. Daniel Czarnocki

AK: What picture started to emerge from the gathered documents?

Again it lies mostly in analyzing the curatorial behavior, trends, and culture. I’m arguing that this is the most advanced iteration of the profession in its development. This is significant when imagining the geographic mass it encompasses and the period of time it represents. When combined with the advanced understanding and implementation of specialized avant-garde cultural production, we’re not talking about art anymore — this is avant-garde culture in the militaristic sense.

AK: How would you describe those in relation to typical curatorial practice?

Leading up to this moment, the curator in the conventional sense of the role was an aggregator. They would collect pre-existing objects from recent or ancient history and put them in a grouping to create a cultural reading of the past or make a conclusion about the present. They were an observer, a collector of objects, and maybe a facilitator. Unless we are discussing patronage, they were traditionally outside of and appearing after the creative process itself.

Starting now with the SCCA Annual Exhibition’s Open Call concept, artists must adapt their practice and way of thinking. It becomes an actual point zero for a wave of controlled creative energy (e.g. ideology) channeled from the curator and emerging through the artists themselves. And whatever it was that emerged was brand new. Using the exhibition as a site of cultural production was not unheard of as many of the early biennials were places for exactly that. But in this case we have a process where, from conception, proposals relevant to the required theme are selected by a board of experts for development. The chosen projects receive funding, unprecedented technical, media support, and guidance.

From this point of view the exhibition becomes the literal birthplace of very advanced new artworks all funded for the Soros Center for Contemporary Art. The language of exhibition-making coming from the Network is very unique to this story. Herculean bureaucratic tactics, reimagining public space, using sacred out-of-context spaces, using the exhibition as an exclusive site of cultural production, using the artist as medium, and most importantly, unifying artistic practices. And as we then see, unifying art worlds. Each of these manifests in an unprecedented way through the Annual Exhibitions and is virally synchronized across the entire network. It was a real force of nature.

AK: What was the role of socially engaged art in the network of CCAs in Eastern and Central Europe?

Certainly socially engaged practice existed prior as artists were always finding subversive, conceptual and performative ways to come up against the system during the period of the “closed society” but again it never happened in such a coordinated and consistent way. It is unlikely socially engaged practice would have emerged naturally in this way that it did after communism due to the reluctance of artists to have their practice again be used for political messaging as it was for socialist realism or have their creativity influenced by a collective urgency.

AK: Which artworks would you highlight as the most disturbing?

I don’t find anything disturbing. I am pro-anomaly and love how much this story demonstrates mutations that we’ve never seen previously.

The Bruce Lee of Mostar (pink version) from Ivan Fijolic is the most incredible case study artwork in the exhibition because it encapsulates this new idea I am proposing of “NGO Art”, which is art made for and by the NGO, and in the case of Bruce Lee had a very profound and long-lasting impact on the way we think about creating public sculpture today. It’s a true artifact.

Maszyna wpływu w Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski. Fot. Daniel Czarnocki

The 1994 exhibition Alchemic Surrender curated by SCCA Kiev Director Marta Kuzma is a profound influence on the conception of this exhibition and its presentation in the political framework of the Ujazdowski Castle. Presented on a live battleship in Crimea, Alchemic Surrender opened a very special doorway to the weaponization of art and context. This event should only be seen as an experiment in tactical media and Public Relations and not as art or even as an exhibition at all. Those are distractions to prevent seeing its true purpose. Inspired by Alchemic Surrender and the creative practice of its curator Marta Kuzma, The Influencing Machine is an invocation of her 1994 exhibition in all senses: recursively as a ritual, a trojan horse and as an curatorial experiment. In the name of art I, Aaron Moulton, have engaged in covert and overt measures which would normally be seen as acts of tactical media, ritual magic, active measures, or disinfo psyops; as a way to pay conceptual homage to this large story of the SCCA and to the under-celebrated story of Marta Kuzma’s exhibition.

AK: Are there any works in the show that were not originally conceived within the Soros’ network? Why did you include them in the show?

There are only a few actual artworks from the Network in the exhibition. As I said, not many important artworks are remembered but rather it’s the curatorial exhibitions that are. Most of the exhibition is about tracing the genetic lineage of socially engaged practice and showing how it creates messaging and activism as the primary function of the artist. It’s only because I have had such a strong dialogue with the artists in the exhibition that this was able to happen. To tell an artist that they are part of a movement is never very welcomed even when it is something celebrated like Pop Art. But in this case I’m asking artists to acknowledge that they have been influenced by this period of the 90s actively or even unconsciously. The real coup de grace is expanding the exhibition to include so many artists who are not from the network or the region at all. This is where the entire enterprise becomes very special as these outsider artists are able to reflect on things from the meta-view and make works about the nature of influence itself.

AK: What was your main concern when preparing the exhibition at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art?

Well I worked in secret for 16 months and swore all of the artists to secrecy because I was afraid of the boycott of the castle from the art world and that leading to a huge public attrition from my project. But I did the smart thing and with each artist had great conversations about the risk and the importance of taking that risk.

AK: Why did you raise a white flag in front of the castle?

Fot. Daniel Czarnocki

To raise a white flag, a surrender flag, is a way to give up and create a “safe space”. But to raise a white flag with any other intention is to create a “false flag”. Pirates would do this as a way to bring in the enemy and then attack. In doing this semiotic action in this political castle, I used it in both senses and was also paying direct homage to the exhibition Alchemic Surrender mentioned before. Marta Kuzma raised white flags around a live battleship in a militarized zone amongst Russian, Ukrainian and other vessels. Was that just a joke? Was it a conceptual readymade playing with semiotics? Was it an act of War? It’s all of these things.

And the “false flag” is of course such an important tactic in perception management today with scripted media events and influence.

Fot. Daniel Czarnocki

AK: What is the line between art activism and global marketing teams seeding content to build not only brand awareness but product demand?

It’s the snake sucking its tail.

AK: If art was used for a great conspiracy now what types of works would we see around ourselves, in public spaces and at the international art fairs?

Any kind of reputational washing or enhancement tactics: greenwashing, wokewashing, other forms of coercive philanthropy done by corporates and privates.

Any way in which creativity is used for a technical intent going outside of the artists’ intent is somehow going to fall in this category, even the contextual work of the curator or museum.

Development of creativity for artificial intelligence would fall under this rubric.

AK: What is the future of art produced by humans when AI can create an appealing artwork in response to a script?

There is such a thing as a universal aesthetic experience that we humans don’t understand. I’ve spoken about this for years as have many sci-fi authors. An algorithm able to use the entirety of human creativity as a dataset will no doubt find a pattern that everyone will see as the most beautiful thing that the human eye has ever experienced. For humans it will be something more than beauty: it will be God. And very likely it will have total control over us through a single image, a pattern. This is a cognitohazardous place. Humans and their creativity will never stand a chance in the face of such a sublime.

AK: Thank you for talking to me. I wish your show to have a great success!