I. SALÒ – AS LIMES

It is generally believed that the most-shocking film by Pier Paolo Pasolini, which administers justice to the contemporary world (and perhaps even a film which is a total, nihilistic, act of opposition to the existence of the world as such), was his last film – Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom – from 1975, based on the libertine novel by D.A.F. Sade, transposed to the time of the fascist Republic of Salò. In this film, four fascist dignitaries – the Duke, the Bishop, the Magistrate, and the President – gather in a picturesque villa to indulge in an orgy of sex and violence involving young people of both genders caught in round-ups. The ritual of violence is divided according to circles denoting specific depravities: the circle of sexual manias, the circle of shit, the circle of blood, and finally the circle of death. Young people, subjected to more or less refined torture, are reduced to the status of bodies without soul, as Pasolini wrote in one of his poems. They are disposable objects in the hands of their executioners, for whom the only legitimacy authorising their limitless perversions is their limitless power. The world of Salò is a world in which power is everything and humanity is nothing. It is a world in which rebellion (almost) doesn’t exist. Because rebellion in a world of permanent violence seems to be impossible. Or otherwise, it is possible, but always doomed to failure.

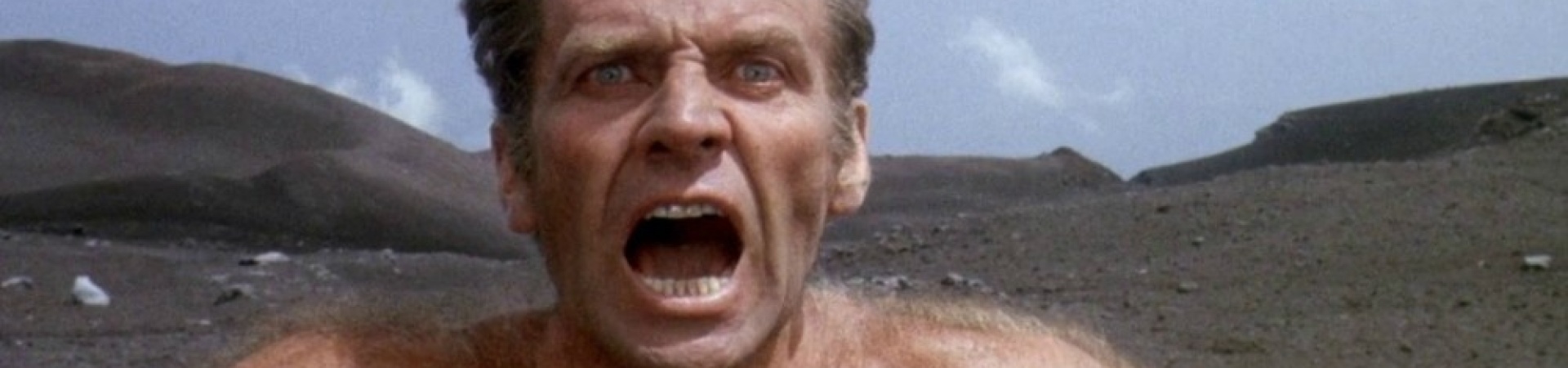

Kadr z filmu Pier P. Pasoliniego Salo, czyli 120 dni Sodomy z 1975 roku

In the soulless world of Salò, indivisible power is held by fascists, for whom art is the only medium which distances them from the carnality in which they immerse themselves. The sadic people of the 20th century are surrounded by Art-Deco artefacts, they quote Baudelaire and Nietzsche, and their radio broadcasts Ezra Pound’s The Cantos and Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana. Unfortunately, this is ostensible distancing. Art, in the space in which sadists vaporise, is a negation of art, understood as a transcendental medium – forcing man to transcend his own carnality. Baudelaire – making sexual excess a surrogate for religious epiphany, opening wide the gates to immanent transcendence; Bataille – with his apology of evil; Nietzsche – with his apparent crusade to save spirituality in man, in fact relegating him to the rank of an animal; Pound – placing the orgiastic Priap in opposition to the ascetic Christ (directly cementing art’s devotion to fascist totalism) and Orff – a neo-pagan, worshipping earth and blood, far from the spiritual transcendence of Christianity. So even the art into whose dominion the anti-heroes of Salò give themselves over to, is anti-art, like Art Deco, equating the ugliness of public-utility objects with ancient sculptures. Spirituality is slain here by aesthetics, or rather anti-aesthetics. The only impulse capable of making perverts tremble is the beauty of the young body, further aroused by spasms of humiliation and suffering. But also, the victims, subjected to the violent treatment, seem truly deprived of their own will, perhaps curious – despite everything – about the surprises prepared for them by the masters of sex and blood.

The film ends with a scene in which the fascist guards start dancing to a waltz coming from the radio, telling each other about their girlfriends. The dance of the two men, with its homosexual overtones, points to a world suspended, without a future, without any chance of rebirth. This ending, showing two dancing young fascists, can be read differently – as Armando Maggi wants, it is the ultimate triumph of life over death, the triumph of life over annihilation and decay.

Is the positive ending really positive? Is a changed world, reduced to corporeality, able to rise from the dead? Or perhaps man’s love for man becomes the only and ultimate equivalent of spirituality, something which allows to transcend, to go beyond the limitations of matter? These are the questions Pasolini leaves us with, without giving a clear answer.

Made in the mid-1970s, the film becomes a vision of the contemporary world: seemingly divided into torturers and victims. In its essence, however, torturers and victims (except for those who rebel) are bodies without souls, seeking in pure consumption, or in art which does not lead to transcendence, but which sanctifies matter, the only goal of their existence. This is the world of Sodom, destined for destruction.

II. SALÒ AS METAPHOR

The hell of Salò – as Pasolini repeatedly stressed in his statements – is not only the hell of war, of the fascist times – the lair of all evil which befell humanity in the 20th century (it is there that the creator of Theorem saw the beginning of the end of Western civilisation, which had made death its totem). All the circles outlined by Pasolini in Salò mark the circles of the reification of contemporary man, who gives himself over to mania, matter, sex, and death. Today, as never before, the world produced by electronic extensions provides man with the immediate satisfaction of all needs, but such that this satisfaction is not total, so that man always craves for more. Similarly, pornography, which, as Foucault aptly observed, never leads to satisfaction, but always to its multiplication. The faeces which the participants in the film’s orgy are forced to eat symbolise the products which contemporary man consumes on a daily basis without thinking about the ingredients used to make them. These faeces are also the content pouring out of the screens and directly into the viewers, who are deprived of the critical mechanisms of rejection and defence. It might seem that the circle of death is the most distant and the most abstract in the Western world. Nothing could be further from the truth. The methods of execution depicted in Salò’s finale are those carried out in many Western countries, especially in the USA. Death sentences are carried out within the majesty of the law, not necessarily on criminals. Legally permitted euthanasia, abortion, suicide on demand due to mental illness, human trafficking, attempts to legitimise paedophilia. The circle of death is like a noose constricting ever tighter around contemporary man in the name of his conformism, self-satisfaction, and unlimited consumerism. “I would like to die before my mother“, Pasolini said in an interview. “I am defenceless seeing her defencelessness; this defencelessness is a sanctity which I am not worthy to touch. When I was little under my mother’s heart, then it seems, I was most happy”. The killing of the defenceless – the youngest and the oldest – was for Pasolini a crime in its purest form – a circle of extreme death, aimed at the essence of humanity.

The line of conflict which marks the face of contemporary reality runs along two lines: one which disagrees with the totality of the body, and another which totally succumbs to the vision of carnality, pleasure, and consumption. The first choice is a heroic one – in totalitarian conditions doomed to failure from the start – and yet necessary in order to preserve the traces of humanity, which does not shun its responsibility, which is the result of fear and pity. Per pieta – out of pity, this is the answer the shepherd gives to Oedipus when asked why he took pity on the abandoned child by saving its life.

III. ANTI-HEROISM AS HEROISM

Heroism in Pasolini? It seems impossible. And yet the entire life writing of the creator of Accattone (1961) was a heroic act. His literature was an emanation of this. “There was no man more courageous than Pasolini” Alberto Moravia would say of the poet. “None of us has reached the same level of courage as him”. The courage of Pasolini’s characters is courage against everyone and everything.

Suicidal heroism is shown by the protagonist of Pigsty (Porcille, 1969) – a film born out of a drama written by Pasolini himself, although classical inspirations shine through. First of all, there is Hamlet – with its protagonist, an individual who is not reconciled with the piggishness of the people in power, including his closest ones, who wallow in debauchery and wealth. Julian Klotz (Jean-Pierre Léaud) – son of a wealthy German industrialist – refuses to come to terms with his father’s Nazi past. He denies his bourgeois, élitist identity, preferring the company of pigs to that of contemporary cannibals who devour their workers, toiling in the sweat of their brow for their starvation wages. Eventually Julian is eaten by the pigs – his rebellion is total and final. He says a blunt no to conformism and piggishness, preferring to be eaten by real pigs rather than be digested by human ones – even, and especially, if he belongs to their class.

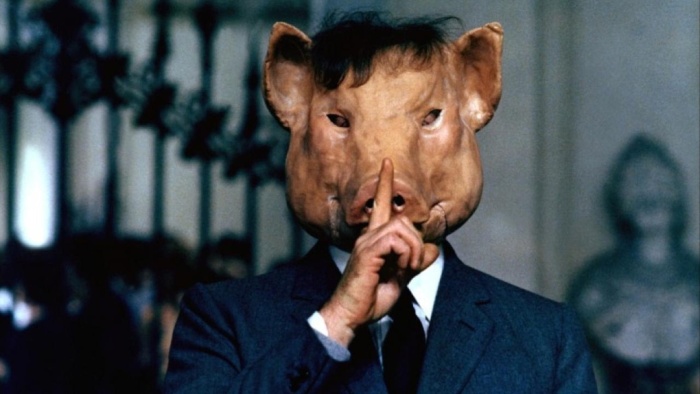

Kadr z filmu Pier P. Pasoliniego Chlew z 1969 r.

Pigsty has a two-threaded structure: the theme of contemporary cannibals is interwoven with a motif from the past, somewhere at the intersection of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, when a story is played out about a band of real cannibals who hunt wanderers traversing deserted roads and wilderness. They are led by a young and daring condottiero (Pierre Clémenti), who does not shy away from any cruelty. The gang first devours animals, then people. In the most-poignant scene, a young family becomes a victim of the cannibals. The acts of violence and cannibalism take place in a barren land, filmed by Pasolini on the slopes of the defunct volcano Etna. It is an infernal, scorched, landscape, just as the interiors of the cannibal bandits are infernal and scorched, and capable only of the trembling caused by murdering and devouring (as the cannibal-condottiero devoured by dogs will confess in the film’s finale).

The world of mediaeval mercenary cannibals presages the world of 20th century cannibals, such as German industrialists with a Nazi past, once making soap out of human beings in concentration camps, now treating people as material to be turned into money, cattle bred on Big Farms made sick and treated for chronic diseases for the rest of their lives, or framed into debts and loans amounting to thousands of dollars, to be repaid for the rest of their lives, in the sweat of their brow and in fear of losing their jobs.

However, there is an ambiguity in the figure of the cannibal condottiero. He is a human monster, and at the same time his cannibalism is a rebellion against the world which allows him to be a cannibal. I am devouring the world which denied me humanity, which did not present me with an alternative to living as a monster – as the anti-hero of the film seems to express with his whole attitude. His confession, shouted out at the moment of his cruel death, that he devoured his father and trembled with pleasure – becomes both an admission of his crimes and a kind of accusation of the world which allowed him to become a monster. This is the Nietzschean last man – the product of a world without values, and its executioner.

Pasolini’s world, ahistorical and historical at the same time, is a world of paradoxes, showing the extraordinary tangle of dependencies, and, at the same time, the lack of them, connecting the two parts of the antagonised world. In the end, however, there is the ultimate division, the final border separating the last man from the first – it is the division between those who are compassionate and those who are devoid of compassion.

IV. A THEOREM – RADICAL REVOLUTION

This is why human/arch-human heroism ultimately comes, manifested in the figure of The Visitor (Terence Stamp), the enigmatic protagonist of Theorem (Teorema, 1968). In making this film, Pasolini starts from the assertion that communion with the Absolute is always a contact leading to transcendence, to the negation of one’s own self. A bourgeois family from Milan, whose representatives enter into a close relationship with The Visitor, experiences a spiritual awakening. The mother first throws herself into the abyss of debauchery, and finally, carnally insatiable, feels hunger for spiritual ecstasy sought in a deserted church. The son will have a homosexual awakening, combined with the discovery of a creative talent. The daughter will fall into a catatonic sleep, completely detaching herself from her body, and entering the space of the spirit. The father – the owner of the factory – will embark on the path of purification, both from the individual perspective (he will shed the shell of the bourgeois, conformist, and egoist) and from a social perspective (he will give the factory to the workers). The housekeeper will transform into a village healer – she will be the simplest emanation of divinity.

Kadr z filmu Pier P. Pasoliniego Teoremat z 1968 r.

Pasolini wanted to include in his film a vision of spiritualised eroticism. To show how God, through direct intervention, a somatic intervention, completely changes a person. The Visitor (especially in the script) is a contemporary embodiment of Dionysus, directly speaking of awakening through physical, sexual, contact. Ambiguity appears in the film, perhaps as a result of the understatements forced by convention. Dionysus becomes more Christ-like, and sexual relations become more conventional. The visitor in the film does not speak; he is silent, like the real God, speaking only through the mouths of angels and prophets. A deep transformation takes place, a metamorphosis of the characters in the film; they become rebels against their own social group, their own limitations, their own masks and shells. The only authentic rebellion which can change man, and which can change society, cannot have its roots in man, must be a superhuman rebellion, whose trajectories are determined by a spiritual force, arriving at the moment of stagnation, solstice, standstill, internal crisis.

Theorem seemingly fits into the counterculture of the 1960s, into the conviction of the only authentic means of communication – the erotic, sexual, bond. At first glance, it shows the genesis of the process which has led the modern Western world to the edge of the abyss of complacency, conformism, the lack of empathy, and the resetting of human reflexes, which the abandonment of responsibility is called today. Theorem is only ostensibly a song in honour of carnality, erotic ecstasy, carnal awakening. Pasolini’s film speaks of an authentic awakening, or a spiritual awakening, which can be contained in an act of amorous, carnal fulfilment, especially if it is an expression of an authentic, interpersonal bond. But it is more a question of discovering in oneself that particle of divinity which turns one human being towards another, arouses in him or her pity, generosity, compassion, sacrifice, all that makes a human being an exceptional, heroic, entity.

V. CHRIST – PASOLINI

The Visitor from Theorem is the Christ in whom Pasolini – a declared atheist – can believe, i.e. God entering into the most-intimate relations with man. Christ, the protagonist of The Gospel According to St. Matthew (ll vangelo secondo Matteo, 1961), the rebel and revolutionary who ignites the war of ideas which continues to this day, is a key figure in Pasolini’s entire oeuvre. He is a model for him in his intransigent attitude of a fighter persisting in his struggle against a world which reifies the individual. A part of Pasolini actually became Christ fighting against spiritual laziness, hypocrisy, and human smallness. Another – as if in fear of losing his humanity, also expressed in his sinfulness and weakness – was (apparently) far from the Christ figure. But Pasolini, in chasing bodies without a soul, was stretched on the cross of his desires, and he retained a remnant of conscience, which today apologists of his work in gay circles explicitly call his part cursed, something he should have rejected in order to fully affirm his own homosexuality. But this would result in Pasolini’s defeat as a human being – total, uncritical, devoid of inner moral trembling; giving oneself over to the Dionysian intoxication would be tantamount to abandoning those who, like Pasolini, wanted to remain human, even at the price of suffering.

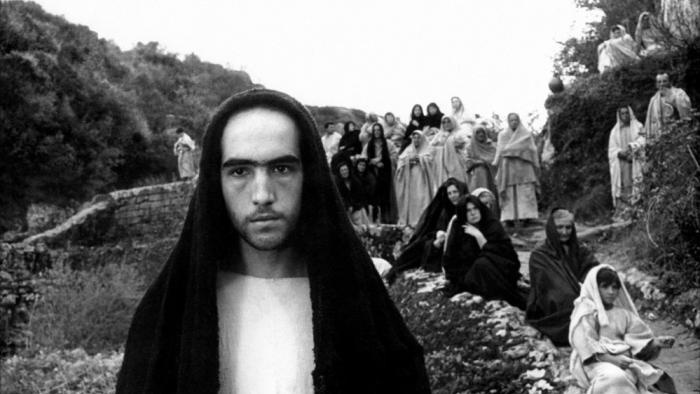

Kard z filmu Pier P. Pasoliniego Ewangelia wg świętego Mateusza z 1961 r.

Christ – Pasolini – as a human being, as an artist, as a martyr to his own sexuality, becomes the holy patron saint for the healing of a fractured world which is incapable of reconciling its glaring contradictions. He points to the spiritual power which can be found in impulses seemingly devoid of it, capable of leading to an awakening, to the resurrection not of the body, but the spiritual body. An attitude of being set apart, of not reconciling with the world and with oneself, of seeking and inducing vibrations in one’s inner self, but in the perspective of communion with another human being, which might be carnal, but is only real if it leads to a spiritual opening, can, according to Pasolini, be a cure for the crisis and the atrophy of the contemporary world, torn apart by conflicts and cultural wars.

It is precisely this being torn apart which is necessary to arouse anxiety, to shake man out of his conformism, to bring him face to face with his destiny, to experience a fall, perhaps, but also, through that fall, to begin to live authentically. To desire again, to suffer, to rejoice, to fight, to lose, but also to rise. So that he finally escapes from Salò – the kingdom of death – where roles have long been allocated, where power, death, violence reign, a man mistakenly convinced that sowing death and not giving life gives him divine omnipotence. Pasolini himself, both through his work and his death, showed that it is something that is more important and greater than man who makes human life continue even after his life is brutally cut short by a body-crushing car, somewhere on a night-time beach in Ostia. Pasolini is even-more alive today than he was when his hyperactivity meant that he could make two films a year, write thirty columns, translate a collection of ancient plays into modern Italian, and act as a tribune at the Italian Communist Party congress, where he condemned the notion of a resolution allowing universal access to abortion.

Pasolini spoke of the need for a state of war, of the need to face the challenges of the world, showing that only contradictions give birth to new ideas, new values, and that they compel people to action. But was the call for revolution, for war, in Pasolini’s case, synonymous with a call to destroy, to cleanse culture? No, because true culture, hiding layers of spirituality, simply cannot be destroyed. Because it lies deep down where no one suspects it exists, in human nature, which, unexpectedly for man, manifests itself brutally, suddenly, violently. Like a spasm, like a sob, like a cry of despair. Like Salò, which, while being a deeply nihilistic film, a film about death triumphing, is above all a call for the other side.

Piotr Kletowski – born in 1975 in Kielce, DSc, Associate Professor at the Jagiellonian University, Assistant Professor at the Institute of the Middle and Far East, on the staff of the Department of Korea. A film and culture expert specialising in the history and anthropology of film, especially Asian cinema. Author of over 100 articles and film-studies publications, including monographs on world-cinema authors (Śmierć jest moim zwycięstwem – kino Takeshiego Kitano [Death is my victory – the cinema of Takeshi Kitano], 2001; Filmowa odyseja Stanleya Kubricka [Stanley Kubrick’s film odyssey], 2006; Pier Paolo Pasolini. Twórczość filmowa [Pier Paolo Pasolini. Film Works], 2013), co-author of extended interviews (with Piotr Marecki) with individual directors of Polish cinema (Żuławski. Przewodnik Krytyki Politycznej [Żuławski. Krytyka Polityczna Guide], 2008, 2019; Królikiewicz. Pracuje dla przyszłości [Królikiewicz. Working for the future], 2011; Piotr Szulkin. Życiopis [Piotr Szulkin. Life story], 2011) and editor of specialist monographs (Europejskie kino gatunków [European genre cinema], volume I, 2016; Europejskie kino gatunków [European genre cinema], volume II, co-op. with Maciej Pepliński, 2019).