2020 is supposed to be a promising year for Rijeka, an ex-industrial harbor city in the northern coastal area of Croatia, in the Kvarner region. As a financially deprived city, in the wake of brain-drain, as well as political, structural, and financial instabilities and historical myths its having once been an alternative place, Rijeka saw the ECoC 2020 project as an opportunity to change things for the better. The expectations, plans, programs, and budgets were huge. But then the COVID-19 pandemic shuttered a large portion of it overnight. Even though the Rijeka 2020 program is still happening, we are now talking about an entirely different set of production conditions – 59 people being laid off, budgets and events reprogrammed, financing reduced… But what actually happened with the Rijeka 2020 program during the pandemic crisis? Is it really the virus that was the main culprit for the layoffs, program cancelations, and lack of funding?

To gain a better insight into the management story of the largest cultural project in Croatia, I talked with Lela Vujanić, (the soon to be ex-) chief program manager of the Kitchen of Diversity program, and Ivana Meštrov, ex-curator of the exhibition programs for Rijeka 2020, within the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art.

M. Tkalčić: For those who are not that familiar with the program of Rijeka 2020 – European Capital of Culture, its dimensions, process of selection and development of the program events, and its significance for the local community – can you tell us more about your own thoughts on the program in general? How was Rijeka 2020 supposed to develop in comparison to what it turned out to be in the wake of the pandemic crisis?

I. Meštrov: Rijeka 2020 was in my opinion initially conceived as a program oriented towards social empowerment and community building. Some of the Rijeka 2020 flagships were: Lungomare – a series of permanent and participative artist interventions set up across the region of Kvarner; 27 Neighborhoods – a participative communal art project fostering local citizen participation and decision-making and Kitchen – a hybrid program merging concerts, socially engaged performances and actions related to migration. In a way, culture was not presented as elite nor taken for granted. Instead, the project demonstrated an awareness of local and global concerns, and the tools of cultural production aimed to act, on a certain level, as the social glue.

Rijeka 2020 – European Cultural Capital positioned itself at the crossroad of certain widespread post-Yugoslav myths and ideas of Rijeka as an alternative, underground city of music and performance, gloomy social realities, and latent social discontents. Unfortunately, in the wake of the pandemic, one became aware of the fragile structural foundations of the largest cultural project in Croatia of the past three decades. On one side, stands the pandemic that turned the world inside out, and on the other the fearful crisis management of the city and the Kvarner region, a lack of financial or any other kind of long-term support from the Croatian Ministry of Culture, and the lack of economic and program autonomy of the ECoC company vs. the final political decision-making. One can understand that all the parties involved were much surprised and heavily shocked by the outbreak of the pandemic, but it is incomprehensible that with their responses they have betrayed, erased, allowed to sink into oblivion, in a way, the above-mentioned Rijeka 2020 program.

L. Vujanić: Rijeka 2020 – ECoC was envisioned as a complete re-imagination of the City of Rijeka, formerly an industrial city, with a rich and often dramatic history related to the concepts of work and migrations, at the symbolic intersection of the ideologies that dominated the last century that resulted in definitive spatial divisions. In the last 30 years of Croatian independence Rijeka has suffered from deindustrialization, brain drain, and general depopulation, with its port (once the largest port in ex-Yugoslavia) working with less than 10% of its capacity. Nevertheless, it succeeded in winning the ECoC title with a programming vision that was supposed to be a breath of fresh air for that old and shabby Austro-Hungarian/Yugoslavian lady.

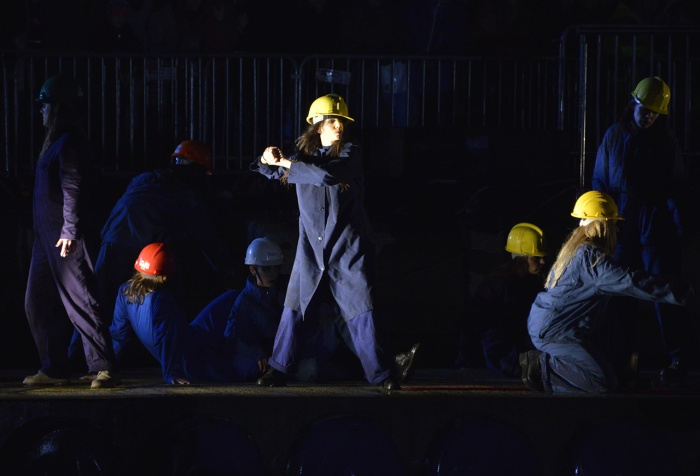

Otwarcie Eurpejskiej Stolicy Kultury w Rijece, 2020. Zdjęcie: Petar Kurschner, (c) Rijeka 2020.

Otwarcie Europejskiej Stolicy Kultury w Rijece, 2020. Zdjęcie: (c) Rijeka 2020.

Some of the formal goals were creating a new cultural infrastructure, supporting the local cultural sector, internationalizing the cultural offers, and bringing new, much needed people into the city. In terms of its program, Rijeka 2020 should have presented and/or (co)produced contemporary art, dealing with relevant social issues and main ECoC themes – water, work, migrations, as well as inspired different local, community-based initiatives and as a result – introduce new agents of social change and new agents of cultural production.

Rijeka 2020 really did succeed in both things, since it started producing events well before its titular year. It also succeeded at having a “grande” opening (1st of February 2020), which was received to general critical acclaim. The opening provoked interest and gained respect for Rijeka in surrounding regions, primarily because it was rooted in the workers’ history of Rijeka and avant-garde art.

And then, with the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis, everything suddenly crashed: the budget, the program, and communication-wise, and it seemed like you were watching Gaspar Noe’s Climax movie – something that was good turning upside down.

How did your collaboration with Rijeka 2020 start? What was (or is) your position within the company? Was your employment contract affected by the COVID-19 crisis?

I. Meštrov: I, myself, joined the project in February 2019 after a successful application to an open call launched at the end of 2018 for the position in The Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, called “the curator of exhibition programs for Rijeka 2020 program.” Quite a vast denominator that comes down to working on several exhibition projects (curating Rijeka-born David Maljković’s With the Collection exhibition; producing the 90s: Scars exhibition and public program dealing with various aspects of art and society of Central and Eastern Europe of the 90s), as well as working on a number of public art projects such as Sanja Iveković’s Monument to Revolution that was cancelled.

My employment contract was affected by the COVID-19 crisis. We were being laid off in the midst of a pandemic, but what is even worse than that, is that most of the projects I’d been working on were cancelled or postponed and heading towards an uncertain future, therefore affecting the long human chain of contributors.

Otwarcie wystawy Davida Maljkovicia With the Collection w Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej i Współczesnej w Rijece, 2020. Zdjęcie: Damir Žižić, dzięki uprzejmości Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej i Współczesnej.

L. Vujanić: I was living in Zagreb and wanted to change jobs, or it would be better to say change my life in general. I saw the Rijeka 2020 job advertisement, applied, and got it. I was attracted mainly by the vision and program laid out in a bid book, but also with the (former) creative team behind the project. I was also attracted by the city itself that I gained familiarity with in the first decade of the 2000s, primarily through its music scene and festivals. So, I was employed as chief program manager of Kitchen of Diversity and spent almost three years, producing different sub-programs under the umbrella of Kitchen and cooperating with various communities present in the city, as well as cultural organizations from Rijeka, Croatia and abroad. The Kitchen identity card says that it is one of 7 flagship programs of Rijeka 2020 concerned with two major themes: migrations and minorities in their local and European context; it runs through different areas of culture (visual arts, literature, performing arts, music, gastronomy, cultural policy). Kitchen was present in the city’s life from 2017 precisely because it is called Kitchen meaning that we produced all the programs that were supposed to happen in 2020 in advance. Now, after the “climax,” I am glad about that decision.

My employment contract was not affected by the COVID-19 crisis, meaning that I was among the “lucky” ones that got the opportunity to remain employed within the project. But anyway, my contract is being terminated now.

At this moment of planetary emergency when we are collectively experiencing personal and existential uncertainties, but as well as systemic and political failures, can you tell us how you see the situation of 59 ECoC employees being laid off, almost overnight? Was this move made by the City Government and Rijeka 2020 representatives justified in your opinion, or can we pinpoint faulty policies in governing this enormous cultural project that were present from the very beginning but have just emerged in this time of crisis? Where exactly do you see the weakest points in management of this project?

I. Meštrov: I strongly disagree with the first official ECoC response to the Corona outbreak – laying off the majority of the workers almost overnight and without any prior debate with the team, or with the public. I imagine that in the midst of a pandemic you are filled with angst. But this response was so self-contradictory. What I find the most cynical about this decision is that one of the three programmatic pillars of the project is WORK and its continuous transformative potential. What do we have here? A call for leisure? Or a strong discrepancy between the programmatic statements and a reality of practical and structural realization of the project? The ideas were here, but were not followed up by practice. We are all due for a big collective therapy, I would say.

Moreover, I think that the project’s biggest flaw was the lack of communication. In a way, the project suffered from a latent ideological battle between the Croatian government and the City of Rijeka (just for the record Rijeka has been a left-wing bastion for over three decades and often in opposition to the prevailing center-right governments).

Also, the management of the crisis revealed the strong hierarchy in the project structure (low or unsatisfactory communication among partners, and restricted project autonomy and decision-making power in comparison to the local government).

Opera Industriale, otwarcie Europejskiej Stolicy Kultury w Rijece, 2020. Zdjęcie: Borko Vukosav, (c) Rijeka 2020.

Opera Industriale, otwarcie Eurpejskiej Stolicy Kultury w Rijece, 2020. Zdjęcie: (c) Rijeka 2020.

L. Vujanić: 59 ECoC workers being laid off at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, came as a huge shock for everybody – those who were laid off, those who stayed as well as for the cultural sector in general. I cannot say (with certainty) what kind of decisions were exactly on the table of those who governed the project. I am sure this was a difficult and traumatic choice for them also. Bearing that in mind, I think that the layoff of 59 workers was unjust given the energy, emotions, and number of working hours that workers invested (especially those in the program department who didn’t work for their salary, but believed in greater ideals about the project). I believe it permanently ruined public trust and the image of the project. Everybody, especially outside Rijeka simply interpreted this “move” as an epitaph for the whole project. It seems now, in the aftermath, that the only possibility for different scenarios in the future is a change in our own understanding of work in culture – an awareness that program values of solidarity and inclusion need to be embedded in our own organizational structure and the work/production process instead of only serving as trendy buzzwords.

How did the local community perceive the ECoC 2020 program developing in Rijeka? What was the public opinion of ECoC 2020 cultural policies during COVID-19 pandemic? For example, there were lots of critiques of the Rijeka 2020 communication strategies, since the huge gap happened between the cultural production on the one hand and communicating the events to the community on the other. It somehow presented Rijeka 2020 and its program as a closed elitist bubble, socially unaware of the city's local community and its needs.

I. Meštrov: The city that flows, as the city is commonly referred to due to its geographical location, has lost in the past decade 8.8 percent of its active population due to economic issues. For sure, it is not an easy task to motivate audiences and the public to take an interest in cultural initiatives in a very tired and deprived city. If I were to refer to the Museum of the Modern and Contemporary Art’s communication strategies and mediation activities it is important to point out that we have moved to a new building in 2017, thus announcing the Cultural Capital program. We were the first residents of the post-industrial complex Benčić which was supposed to be turned into an Art and Culture District, bringing together the Rijeka Public Library, quite a unique project of Children's House, Museum of the City and MMSU.

budowa Biblioteki Miejskiej w Rijece, 2020. Zdjęcie: (c) Rijeka 2020.

budowa Biblioteki Miejskiej w Rijece, 2020. Zdjecie: (c) Rijeka 2020.

budowa centrum kultury dla dzieci Children's House, Rijeka 2020. Zdjęcie: (c) Rijeka 2020.

Museum’s projects such as Dopolavoro or Risk Change, sometimes aiming at specific publics, or tackling topics such as migration were the ones trying to affirm the museum as a relevant cultural and social body in the city, opening a dialogue with its citizens on current local issues and offering a socially conscious program of pastime activities for them. As for the general ECoC project, at the beginning there was a lot of enthusiasm for the project, even though the local community sometimes naively, in a way, expected the cultural project to magically repair social problems and bring more visible changes.

Then the pandemic came, and the financial manipulations, and problems prior to the pandemic were revealed. In a way, after that, suspicions arose, and people were starting to lose interest for Rijeka 2020. These days when you walk across the city the only remnant of the enthusiastic ECoC opening and other program activities are the symbolic red flags still waving across the city.

L. Vujanić: I was working within the program sector, responsible for creating a plan for and producing ECoC events. The Communication and marketing, as well as legal and finance departments were separate but were supposed to serve the events’ needs. In practice, it often seemed that these sectors were not exactly on the same page. I believe that the main problem was our legal entity – LLC, which mirrored a corporate-like structure and resulted in perceiving marketing as building a corpo-brand and selling tickets. Another problem was that our own work in the programming department was strangled with bureaucracy and administration. But both of these trends (concerning marketing and administration) were introduced in the cultural sector long before Rijeka won the title. Consequently, beautiful jobs in the cultural sector are becoming increasingly what David Greaber calls bullshit jobs, detached from the real needs and aspirations of the majority of the citizens.

It seems to me what we’re facing here is the global policies of the capitalist system in the terms of cultural production. We became painfully aware of the cultural workers' precariousness, while at the same time the cultural and political representatives didn’t want to give up on the production of the Rijeka 2020 program. Can you give us your view on it, and your opinion on the current situation with the ECoC 2020 program as well as its impact on the city which is on the verge of bankruptcy?

I. Meštrov: In the most fragile of times the precariousness of a (cultural) worker is clearly revealed. So is the cruelty of the neoliberal system. Future perspectives for the workers in culture on the national level are very narrow. Solidarity is scarce too. Cultural work doesn’t have a strong support in Croatian mainstream media , because it is considered to be parasitic which I find ravaging.

In a way, with this European Cultural Capital, at last we had better working conditions and support financially and production-wise. Then the virus arrived, posing a real sanitary and health issue, not only serving as an argument to cut those much needed financial backing for culture in an everlasting unstable surrounding, but also contradicting the sole nature of contemporary cultural production that counts on social contact, interaction, participation, and physical presence.

L. Vujanić: You are right. The crisis has just radicalized the precarity and vulnerability that already existed in the cultural sector. We all (in institutions and NGOs alike) are continuing on with business as usual, producing or even hyper-producing events, regardless of our shrinking program budgets and personal resources. On the other hand, there are different initiatives, nationally and globally, which are calling for a different design of the cultural system (rather than production of more programs and events) that will be more robust or, it would be better to say, resilient, that will emphasize the mutual connection of all elements of the system (instead of their competitiveness), and that will bring a diversity of culture producers and workers to the fore.

Based on the experiences so far, can we at least try to predict or imagine what the outcomes of the ECoC 2020 project for Rijeka and Croatia will be in general? Do these sorts of mega-cultural events have certain mechanisms and power to affect the society in a positive manner, to bring a prosperous change, or are we just observers of people playing politics?

I. Meštrov: Of course, playing politics was evident especially when confronted with the way the crisis was treated. For me, and a lot of us, once the major part of the workers participating in the program development were so bluntly laid off, the program lost its overall integrity. So, even if some of its parts will be produced and delivered after all, the project has lost its authentic basis and context.

That is why I think that the past and upcoming ECoC realizations won’t have the immediate recognition, public approval nor “transformative power,” but one could say that it’s an investment in the future (I hope it doesn’t sound that cynical or desperate as it resonates in my mind). In a way, the scarce remains of the program are being delivered and wrapped up at least for the so-called delayed audience of citizens/practitioners, which is in a way an accidental conceptual strategy. So, I find this interesting. Time will tell.

L. Vujanić: I’m sure that the Rijeka ECoC will have many positive outcomes – in terms of new cultural infrastructure, permanent artistic installations (program Lungomare Art), established local, community-based initiatives many of which are happening in rural and remote areas (the event27 Neighborhoods), etc. On the other hand, I believe that the ECoC project in general has many internal flaws – it relies heavily on local and national financing in already impoverished countries with unstable/insufficient cultural funding; it promotes social inclusion and equality while expecting the cultural sector alone to somehow implement those values in practice, while leaving economic policies intact, etc.

So, to sum up, I would say that we do not need more mega events or more business as usual. What we need are completely different social relations, or as philosopher Paul B. Preciado puts it, different relations with everything that surrounds us: “To stay alive, to maintain life as a planet, in the face of the virus, but also in the face of the effects of centuries of ecological and cultural destruction, means implementing new structural forms of global cooperation. Just as the virus mutates, if we want to resist submission, we must also mutate.”

BIO

Marina Tkalčić works as project leader and curator of the EU project Risk Change in the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rijeka. She holds an MA in Museology and Heritage Management, and Cultural Anthropology from the University of Zagreb. She is the author of several papers published in peer-reviewed journals, and dozens of in-depth interviews with artists, activists, and experts from the field of art, activism, and ecology in the area of southeastern Europe. Her main research and curatorial interests are socially engaged and activist art, ethics, and politics of care within curatorial agency, eco-activism, and critical pedagogy, and theories of ritual and myth.

Lela Vujanić was born in the worst and most beautiful neighborhood ever, the Sisak Iron and Steel Factory, where artists molded and crafted iron sculptures, so the aesthetics and themes are very industrial. She graduated in philosophy and comparative literature in Zagreb. She landed in New York in 2011, just as the Occupy movement was starting, and used her prestigious Fulbright scholarship in a less prestigious way, by visiting the occupations and researching radical American policies. Being a tireless worker, she organized festivals, conferences on self-organization, produced obscure TV shows; she was an editor of marginal magazines such as 04 – Magazine for hacking reality. She is a proud member of the Women’s Anti-Fascist Network of Zagreb. The printed word is her passion, and social movements her inspiration. She can’t decide if she is in favor of fully abolishing labor or making work available to everyone.

Ivana Meštrov is an art historian and curator. She combines her curatorial practice with academic research and temporary lecturing positions (the Art History Department of the University of Split; Academy of Applied Arts in Rijeka). She obtained her diploma from Pantheon-Sorbonne University Paris 1 as well as attended session 12 of the curatorial training program Ecole du Magasin, Grenoble. She has co-founded Zagreb based NGO Loose Associations Contemporary Art Practices as well as an independent educational program Kustoska platforma (curatorial platform) running since 2008. Through her curatorial practice she questions the habitual patterns of exhibition making and the possibilities of translating these processes into other constellations/relationships through various spatial possibilities, media, duration and perception experiments, and experimenting various modalities of collective work. She often writes and does research about public art, as well as social and political potentials of collectivism through art channeling.

*Cover photo: Opera Industriale, opening of European Capital of Culture in Rijeka, 2020. Photo: (c) Rijeka 2020.