In November 2014, the Public Movement art collective carried out a performative, participative, and durational procession titled Cross Section along Tryokhsvyatytelska Street1 in Kyiv, with the final destination at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs building. Based on research of the Euromaidan and using the mechanisms of social choreography, the artwork raised the questions of leadership and responsibility, power and the individual and their possible reactions to the government’s actions in emergency situations. The procession involved various “acts” and “rituals” which allowed the viewers/participants to live or re-live their recent traumatic experience. One of these acts used the Positions performance, in which the participants were asked questions whose provocativeness grew over time, but the participant needed to make a single choice and take a position. One of the questions was: “Maidan: is it already in the past, or is it our future?” Opinions diverged. People split up and established their own positions. After six years, it is still hard to answer this question; but we can say with confidence that Maidan has become a historic boundary which divided life into “before” and “after,” read: before and during the war.

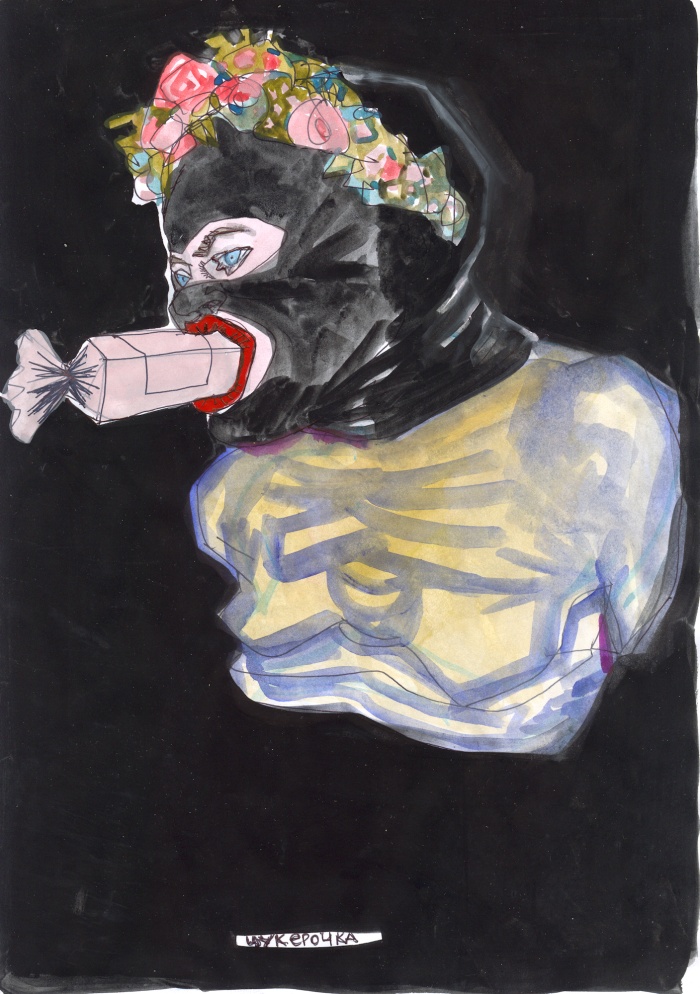

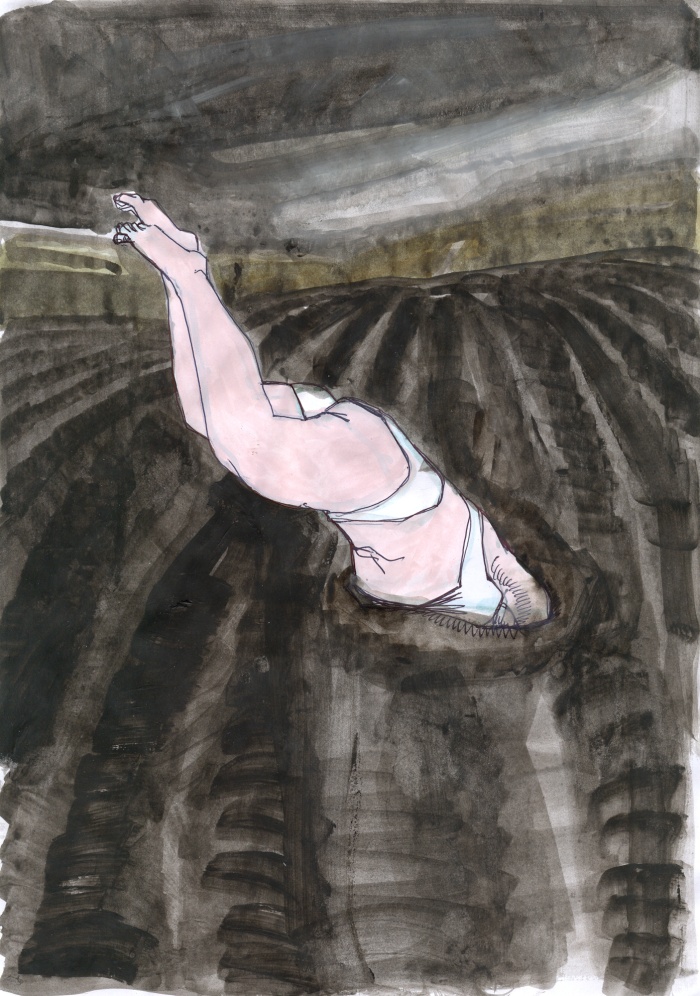

The processual performance by Public Movement, which involved about 100 participants, recreated the emotion of unity as a reminder of the first stage of the Maidan events, dominated by the atmosphere of unity, brotherhood, singing together and other euphorically tinged collective actions. Very soon, the whole situation became violent, communication was suppressed by forced pressure from both sides. The instant change of events transformed the reality into a chain of surreal events when the Independence Square resembled a Medieval battle scene with all its essence. “Never mind how: for a while, I suspended my ability to tell apart real events and metaphors,”2 noted the artist Vlada Ralko in her Kyiv Diary (2013–2015), which is a simultaneously subjective and reliable “document” of the time. Very aptly, Ralko noted this boundary of unawareness of the perception of the real and the virtual, the imagined and the things happening right before your eyes: “I often used deliberately absurd or unreal imagery to document real events with utmost precision.”3

Włada Rałko, praca z serii Dziennik kijowski, 2013-2015. Rysunki długopisem oraz akwarelą na papierze. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Włada Rałko, praca z serii Dziennik kijowski, 2013-2015. Rysunki długopisem oraz akwarelą na papierze. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Włada Rałko, praca z serii Dziennik kijowski, 2013-2015. Rysunki długopisem oraz akwarelą na papierze. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Włada Rałko, praca z serii Dziennik kijowski, 2013-2015. Rysunki długopisem oraz akwarelą na papierze. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Włada Rałko, praca z serii Dziennik kijowski, 2013-2015. Rysunki długopisem oraz akwarelą na papierze. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Włada Rałko, praca z serii Dziennik kijowski, 2013-2015. Rysunki długopisem oraz akwarelą na papierze. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

The feeling of euphoria united people against the common enemy: the president, the government, their chosen political orientation. The media always emphasized this uniting force of the revolution, facilitated by the moderate “concern” of the European leaders. The general pathos of “victory” over the president who fled the country, of the revolution itself, of the Maidan, was also accompanied by multiple pains: deaths, ruined histories, lost hopes, and then also by the war which resulted from unresolved issues and political abscesses that had opened up.

This puss-filled underlayer was reflected in Vlada Ralko’s Kyiv Diary, which was mentioned above. The artist created it as automatic writing, with hardly any distance, from within the events – right here and now, driven by the feeling of empathy for the protesters, thinking first and foremost about the nature of the human, about the possibility of a place for humanity in the stream of violence.

Sasza Kurmaz, Wasze ofiary były na marne!, 2018. Dokumentacja fotograficzna akcji na kijowskim cmentarzu. Akcja jest częścią projektu Kronika bieżących wydarzeń. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Already in 2018, the artist Sasha Kurmaz carried out the campaign Your Sacrifices Were in Vain!. This telling slogan, like no other, described the whole tragedy of the lost euphoria and the triumph of fatigue in the situation of war which had lasted without pause for seven years. This action asks a deeper question. It does not just address the current war – rather, it addresses the uninvestigated (covered by the necessity of war) first the murders in Maidan, back in January–February 2014. In this artwork, the artist rejects any “hierarchy” of victimhood depending on ideological identity, professional occupation, gender and so on. He speaks about the universality of death, responsibility for life (both one’s own and the Other’s), contemplating the powerlessness of art before life itself. What can art do in this case? What image can be compared to the image created by life itself? How do you get rid of the “burnt smell,” if it follows you everywhere, wherever you run? The war has introduced its own corrections, changing not just the geographic, but also the political, socioeconomic, and cultural landscape.

Jarosław Futymski, performans Kim są ci wszyscy ludzie, którzy widzieli ten sam krajobraz?, 2018. Dokumentacja fotograficzna. Dzięki uprzejmości wirtualnej przestrzeni wystawienniczej Shukhliada.

In his performance Who are all these people who have seen the same landscape?4 (2018), Yaroslav Futymskyi addresses a workers’ strike at a paper factory in 1905 in Poninka, Khmelnytsky Region, which is the artist’s hometown. During the performance, the artist stands alone against the background of a desolate landscape, on a big rock surrounded by water, on the location where the 1905 strike is supposed to have taken place. His left hand, wrapped in fire-resistant material, is raised and burning. It’s as if it’s not a hand at all, but a torch; as if the artist is not a person, but a living monument. “The revolution has lost, and the memory of it is being erased or moving into the sphere of phantoms and utopias,” writes the artist Nikita Kadan about this work.5 Based on the revolutionary events of the past and appealing to individual and collective memory, Futymskyi, from the historical perspective, asks the question, What constructs today’s political landscape? How can this landscape be perceived in the future?

Anna Zwiagnicewa, Narysować własne okno, zmiąć papier, 2015. Pręty zbrojeniowe, spaw, żelazny drut. Na zdjęciu Ira Mirosznikowa, Studio Architektowniczne FORMA (Kijów). Dzięki uprzejmości Studia Architektonicznego FORMA.

In her work To draw your own window, to crumple the paper (2015), Anna Zvyagintseva actually captures the state of today’s political landscape, emphasizing its fragility. The landscape changes very quickly, falling apart right here and now. The artist captures the impossibility of an unbiased holistic gaze, the impossibility of grasping the reality which is changing right before your eyes. This work makes us think about reevaluating our values, when routine, calm, and confidence in tomorrow become the most significant things in life.

Kateryna Jermolajewa, Blokada wspomnień, 2015. Mural, akryl na płycie piankowej, rzeczy osobiste. Zdjęcie: Siergiej Illin, (c) PinchukArtCentre, 2015.

Kateryna Jermolajewa, Blokada wspomnień, 2015. Mural, akryl na płycie piankowej, rzeczy osobiste. Zdjęcie: Siergiej Illin, (c) PinchukArtCentre, 2015.

While Zvyagintseva’s thoughts about the military landscape emerge as remote reflections of a conscious citizen and artist, The Blockade of Memories (2015) by Katerina Yermolayeva is based on personal experiences and memories related to her home in Donetsk, where she spent her childhood and adolescence. Today, her family is separated by war, it is impossible to touch the true memories preserved in some things which have also gained greater value than before. Automatic writing, mentioned in the context of Vlada Ralko’s work, gains a different meaning here. At the level of motor skills, long lost memories have started to emerge and manifest, when visual images began to appear through the act of uninterrupted hours of drawing on the walls, thereby performing a mnemonic function.

Gazing into the past – both personal and historic (national, cultural heritage, blind spots in history) – has determined Ukrainian art since 2014, prioritizing the desire to figure out oneself and one’s memory before moving forward. The art is addressed to the past or the present, which is portrayed as either too traumatic or socially oriented. In any case, this is the present which leaves no room for the future. This escape into the past might be linked to art’s helplessness in the face of violence. In these difficult circumstances, there is a gesture in the present. Vova Vorotniov’s work Za_s_xid [W/East] (2018) is an example of how a simple artistic and social experiment gains this power. The artist walked across Ukraine, from his hometown of Chervonohrad in the Lviv Region to Lysychansk in the Luhansk Region, to exchange coal from one mine for coal from another. The title of the artwork is hard to translate into any other language, because it becomes a linguistic game where the words “east” and “west” are different in their first letters only, and therefore, already at the linguistic level it expresses the features of unity, similarity, and, of course, regional uniqueness, which is what makes the regions culturally rich. As he walked across the whole of Ukraine, the artist recorded various places and locations, landscapes and the way everyday life is organized on his Instagram page. This emphasized, deliberate mundanity is what makes us similar to one another. “This personal living-through is more important to me than any external effect,” commented Vorotniov.6 However, for the Ukrainian art milieu, his personal experience became an external effect, an understanding of how one can reach beyond the conventional critical art, beyond social networks and technologies; with this kind of archaic gesture (walking across the country on foot from west to east), Vorotniov created a multilayered artistic image, presenting an opportunity to talk about the problems of ethics and the uncompromising nature of the artistic gesture.

Wowa Worotniew, dokumentacja fotograficzna projektu Za_s_xid [Za/wschód], 2017. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Wowa Worotniew, dokumentacja fotograficzna projektu Za_s_xid [Za/wschód], 2017. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Wowa Worotniew, dokumentacja fotograficzna projektu Za_s_xid [Za/wschód], 2017. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Today, a Ukrainian artist finds him/herself in a difficult, ambiguous situation. He/she is expected to deal with the topics of violence and oppression, to conceptualize the revolution and war. If art practice is not aimed at conceptualizing a military conflict or the totalitarian past, it is hard (or practically impossible) for the artist to find his/her place in the international art field. However, the questions of responsibility, the integrity of state borders, the fragmentation of worldview, post-truth and informational manipulation, provoked by the post-2014 situation, have affirmed the realization of the impossibility of the “correct” (or the only correct) and the questioning of any normativity.

In this issue, we cannot encompass all the practices and the plurality of voices, but we would like to emphasize the emergence of an important association, the Luhansk Contemporary Diaspora (https://lkd-dragon.bandcamp.com/album/vostok), which appeared in 2015 as an artistic union of artists and musicians who were displaced by the war. Today, the association includes sound artists who live on both sides of the separation line. The basis of their language is still electronic music, in which freedom and the right to expression dominate over physical borders, conflicts, and war.

Touching upon the fragility of borders, labor migration, and a shifting political landscape, violence and the public field, the nature of compromise and uncompromisingness as a vanishing form of artistic expression, this special issue addresses identity and questions any need for identification in the modern world.

Translated from Russian by Roksolana Mashkova

BIO

Kateryna Iakovlenko is a contemporary art researcher, art critic and journalist. She got an MA in journalism and social communication at the Donetsk National University. For six years she has been researching transformation of the heroic narrative of Donbas through new media as a postgraduate thesis at the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv. For more than seven years she has been writing about art and culture in various Ukrainian and European media. Worked as deputy web editor in The Day newspaper (2013-2014), and curator and program manager in Donbas Studies Research Project at the IZOLYATSIA, platform for cultural initiatives (2014-2015). Her current research interest touches on the subject of art during political transformations and war, and explores women's and gender optics in visual culture. She was the editor of the books Gender Studies by Donbas Studies Research Project (2015) and Why There Are Great Women Artists in Ukrainian Art (2019). Now she works as a researcher and public programme curator at the PinchukArtCentre.

Tatiana Kochubinska is an independent curator, writer and lecturer based in Kyiv. Her main expertise is Ukrainian contemporary art. In 2016–2019 she curated the Research Platform of the PinchukArtCentre, where she was engaged in curating, research and publication programmes. She edited the book PARCOMMUNE. Place. Community. Phenomenon devoted to Kyiv squatting group. In her curatorial practice, Tatiana deals with questions of responsibilities, memory, and trauma, connecting the Soviet past with today’s society. This is reflected in a series of exhibitions such as Guilt (2016), Anonymous Society (2017), and Motherland on Fire (2017). She curated the PinchukArtCentre Prize in 2015 and 2018 and co-curated Future Generation Art Prize in 2019 and the FGAP@Venice as a collateral event of the 58th Venice Biennale. In 2020 she co-curated Almost There online exhibition within the British Council project Museum Without Walls.

* Cover photo: Roman Himey, Yarema Malashchuk, New Jerusalem, 2020. Still from the documentary film. Courtesy of the artists.

[1] Triokhsvyatytelska Street is near the Ukrainian House, where confrontations between the protesters and the law enforcement took place during the Revolution of Dignity in January–February 2014.

[2] Ralko, Vlada. Kyivskyi schodennyk [The Kyiv Diary]. Kyiv: ArtHuss, 2017, p. 10.

[3] Ibid. p. 7.

[4] The project was created especially for the experimental virtual environment Shukhliada (https://shukhliada.com/#/menu). Curated by Ksenia Malykh.

[5] Kadan, Nikita. Prizraki [Ghosts], Рrostory, January 23, 2019. — https://prostory.net.ua/ua/krytyka/442-prizraki

[6] Vova Vorotnev: o radikalnykh zhestakh, contrnostalgii po sovetskomu i stanovlenii v 1990-ye [Vova Vorotniov: On Radical Gestures, Counter-Nostalgia for the Soviet, and Coming of Age in the 1990s], Your Art, September 30, 2019. – https://supportyourart.com/conversations/vovavorotnio