Throughout its history Ukraine has been constructing politics, entering alliances with the East or the West, and searching for its own middle path. Double articulation, as an attempt to find itself, characterizes Ukraine geographically and historically. Seeking unity, Ukraine finds it hard to admit the complexity of its own identity, and the Maidan events have revealed a complex, long-lasting conflict associated with a clash of different concepts of the world and stereotypically developed ideas about the East and the West (read: Russia and Europe) on the level of both symbols and political forces. It seems that artistic practice combines these two levels: reacting to political forces, the artist expresses his/her attitude through the language of art. However, the tragic nature of the Maidan events demonstrated that art is powerless in the face of real violence.

We spoke with Sergey Bratkov and Yuri Leiderman, two artists who came to the fore in the late 1980s, at the end of the USSR’s existence: one in Kharkov, the other between Odessa and Moscow. They both have complex identities and are important opinion-makers for Ukrainian art as well as various artistic and intellectual communities. Bratkov is a citizen of Ukraine who lives in Moscow; Leiderman is a citizen of the Russian Federation who lives in Berlin. Both are embodiments of the historic Ukrainian ambivalence.

We asked them about how they perceived their experiences of the Maidan events, about how the clashes of perspectives and worldviews were reflected in art, in their relationships with their colleagues, and why these events helped turn many contemporary art practices into “excavations” of historical correctness.

Siergiej Bratkow, Nas tu nie ma, 2018. Neon, plastikowa paleta. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Tatiana Kochubinska: Few people could remain indifferent to the revolutionary events of the Euromaidan in November–December 2013. Information about them took over the front pages of the media across the world. What shaped your perspective of the events at that point? How was it possible to make up your own mind about what was happening amid all the different opinions, conflicts, arguments, and disputes?

Sergey Bratkov: There is a widespread opinion that with age, people get more engaged in politics than young people. It’s true. They monitor politics because interesting, intriguing things are happening there. Of course, I check in and look through political analyses. When I was preparing for an exhibition at the PinchukArtCentre,1 I travelled to take photos of Ukraine. I photographed a lot in Donbas. And this was “Yanukovych's Donbas.”2 I was struck by its poverty. When you left the highway to drive in the direction of Donbas, you could see a pile of concrete slabs and people tearing the iron rods out of them. Cemeteries at the feet of slag heaps dug into your memory, as well as the flattened slag heaps themselves which emitted sulfur odors. It was impossible to stand up there, so strong was the sulfur smell. I saw people mining coal in makeshift illegal mines, I saw Donbas soil turned over for illegal quarries, I saw how damaged their roads were, as if tortured by tanks. So my attitude to Yanukovych was unequivocal. I felt like Donbas was much worse as a place than Kharkov or Kharkov Region. I was surprised to see the Soviet discipline in Donetsk itself: everything was so athletic, lean, and strict. Also, the figure of the president himself – he was an ex-convict and clearly an ex-con – should have resigned from power. I felt, and I still do, that people’s actions against Yanukovych’s government were proper and inevitable. No mass media could sway me. During the events, I came to Kyiv three times to take pictures. Twice during the revolutionary events, once right after the mass shooting in Instytutska Street. The live feeds – naturally, it was striking. I watched the final act of that “bloody play” all night. Online, of course. I threw my TV away when I moved to Moscow, back in 1999. The Russian sources for me were the Echo of Moscow and Novaya Gazeta, and the Ukrainian ones were the 5th Channel and Ukrayinska Pravda. Mostly Ukrayinska Pravda, at that point.

Siergiej Bratkow, Majdan, 2014. Wydruk kolorowy. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

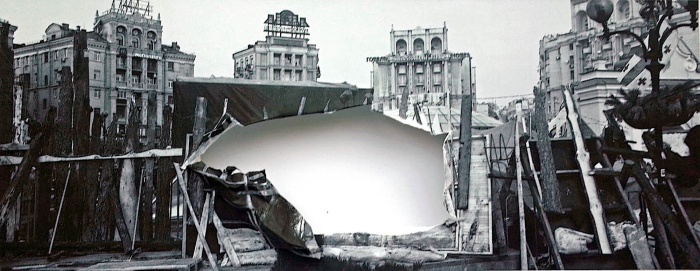

Siergiej Bratkow, Przełamane barykady, 2014. Kolaż, czarno-biała fotografia, aluminium, ręcznie modyfikowane. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Siergiej Bratkow, z serii Ukraina, 2009. Wydruk kolorowy. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

It was important for me to visit Ukraine at that historic time, and I still have documents concerning it. In addition, I visited with a student of mine, the artist Oleg Ustinov. It was important for me that he felt and saw for himself what kind of people they were. We arrived in Kyiv early in the morning, when the protesters entered the Ukrainian House; the windows that had just been broken were covered with plywood. We were welcomed there, we spoke Russian. Of course, Oleg was surprised, he had heard different political news, he had heard about “fascists.” When we came into the room where tired people were lying randomly on the floor, with their motorbike helmets off, with sticks lying next to them, they made room, let us in to warm up, freed a power socket to let us charge our phones, gave us tea with honey. Of course, this made a strong impression on a guy for whom the Maidan was something entirely different.

The trip to Kyiv was, in a sense, in search of a different truth – not the truth broadcasted in the news. But what do you think about the fact that at an early stage of the revolutionary events, the Kyiv City Administration facade was covered with a huge banner with a portrait of Stepan Bandera?

You know what I think about it. You remember the nationalists’ “flashmob” at the PinchukArtCentre during my exhibition and their threats against me. My attitude to this is bad, of course. I can tell you honestly that, thank god, I didn’t have any problems with nationalists at that point, when I visited the Ukrainian House, the administration – I was curious about everything.

The revolution and the events that followed, such as the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas, caused numerous conflicts in art circles. Did they affect your relationships with your colleagues, and was it reflected in your art? How effective, in your opinion, is the method of boycott, used in situations of conflict?

I had a tense relationship with Sergey Zarva,3 with whom we used to have joint exhibitions. When we were at Ilia Isupov’s4 during one of our visits, Zarva called us to the phone one by one, told us a lot of bad explicit words and left for Kerch. After this, I met him in Moscow, and it was a cold relationship. Recently, it has all warmed up and Zarva himself has changed, stopped being so radical, he even regrets to some extent that he had to leave Odessa. Boycott is like an unbalanced scale, when one pane of public statements outweighs the other, on which the considerable weight of a person’s social status, his stability, material welfare, maybe even freedom rests. Then a boycott becomes significant within this weight ratio. In practice, with today’s art personalities, boycott is ineffective, because today, it’s hard to find personalities who would not be focused on self-PR, who would have a crystal clear moral and ethical reputation. At the time of the MANIFESTA5 in Saint-Petersburg, probably the only person who could’ve been effective with a boycott, at least who could affect me, would’ve been Boris Mikhailov. But maybe for artists from a different generation this would be different.

But this applies to public boycotts. There’s another kind – the silent, “Solzhenitsian” kind of boycott which works not on the Ukrainian but on the Russian side, where the regime is more totalitarian. Solzhenitsyn said that a civic position means that everyone must become a wall blocking the spread of lies, untruths. And if you don’t support the lies – that’s a boycott. For instance, for me, my internal boycott is “I don’t go to Crimea.” And I think that this silent boycott does what it’s supposed to do without any promotion when it’s maintained en masse.

Siergiej Bratkow, Rejestracja, 2014. Kolaż cyfrowy. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

You developed as an artist in the late 1980s–early 1990s, the time when the USSR was collapsing. Was the question of identity important for you back then, and what is the role of citizenship in it?

To be honest, getting citizenship, losing citizenship, this is a procedure of a violent nature, which limits people’s freedom. It is traumatic for me. Since the Soviet times, I’ve tried to never deal with government agencies. As much as possible, I’ve avoided going to the Housing Management Office or the Accounting Department. So I don’t have Russian citizenship. Also, and this is very important for me, I promised my mom to look after my brother and not to leave my parents’ home near Kharkov forever. The question of identity with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the establishment of Ukraine – I remember the day when I went to sleep named Sergey and woke up named Serhiy. It was a shock for me. It felt very unfair, especially for artists, for whom their names are actually important, because they are identified by their names. You know we were concerned about this issue. With the Fast Reaction Group,6 we reflected the issues of identity in our works, primarily in If I Were a German (1994), I Spitting on Moscow (1994), Guards (1997), and A Box for Three Letters (1994). We, our group, reacted to this issue of identity like nobody else. By some miracle, I got the Innovation Prize7 in Russia as a citizen of Ukraine. But with the Kandinsky Prize, I’m disenfranchised. It’s unpleasant, but there’s nothing I can do.

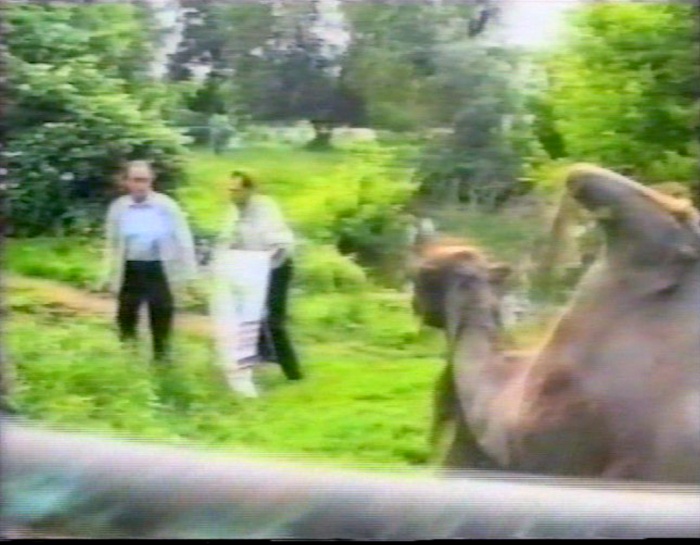

Grupa szybkiego reagowania, Plucie na Moskwę!, kadr z wideo dokumentującego perfromans w przestrzeni publicznej charkowskiego zoo, Ukraina, 1994. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Grupa szybkiego reagowania, Plucie na Moskwę!, kadr z wideo dokumentującego perfromans w przestrzeni publicznej charkowskiego zoo, Ukraina, 1994. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Grupa szybkiego reagowania, Plucie na Moskwę!, kadr z wideo dokumentującego perfromans w przestrzeni publicznej charkowskiego zoo, Ukraina, 1994. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Have you ever wanted to return to Ukraine or even move somewhere else entirely?

The Earth is round. I tell myself every year that I’m going to stop teaching and be a free man, and maybe I’ll change my place of residence.

After the revolutionary events, the so-called “memory battles” and deliberations about the past happened. The practice of many young Ukrainian artists is based on a conceptualization of the historic processes of the past. What is the reason behind this orientation, and what is important in art for you?

Turning to the past is both nostalgia and a kind of retrospection. Nostalgia is a loss of home, a longing for what’s been lost. It’s a great missing for the home that doesn’t exist. At the same time, it’s also dissatisfaction with one’s current home, life, circumstances. The longing is also transmitted through family members. We should keep in mind that all young people are attracted to attics and cemeteries. And old people like to go to funerals, to see how others are leaving this life. These are natural things. Retrospection is different from postmodernism with its quoting of the classics. Today, it’s become trendy to study things that aren’t obvious or significant, things that are on the verge of extinction. The artist becomes the hero of our time – a savior, a missionary.

I want to be a big part of the present, to believe in the power of art, that it can do something, and that you can do something in it. To believe that in the power exercise with human freedom, art can lift some weight.

Siergiej Bratkow, Wyjechać Zapomnieć, 2013. Neon, wydruk cyfrowy. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Siergiej Bratkow, Niech żyje to co złe dziś, by jutro było dobre, 2010. Wydruk cyfrowy, neon.

How connected, in your opinion, are the issues of morality, ethics, and art? How necessary and how possible is it to separate your personal stance from your artistic stance?

The position of doing art without showing off your activity resonates with me. I’m not a fan of art in words, I’m not a supporter of accompanying texts, and in this sense, I’m old-fashioned. I don’t like the “bourgeois left” at the institutions. In Kyiv, many artists I know participated in the Revolution of Dignity and supported the country's European path of development, but when they face the option of losing the cheap government-provided workshops of the Association of Artists, their “Euroenthusiasm” vanishes. I don’t know, maybe I’d think the same way if I lived in Ukraine.

Translated from Russian by Roksolana Mashkova

BIO

Sergey Bratkov (born 1960 in Kharkov, USSR) is a multidisciplinary Ukrainian artist based in Moscow. His artistic practice embraces photography, painting, performance, video, and (video)installation. He graduated from the Repin Art College in 1978 and the Polytechnic Institute in 1983 both in Kharkov. He was a part of the Litera A artists group from 1988 until 1993 and a part of the Fast Reaction Group together with Boris Mikhailov and Sergey Solonsky from 1994 until 1997. In his studio, he organized an artist-run gallery space, Up/Down, which was active in Kharkov from 1994 until 1997. Since 2000, he has been living and working in Moscow, where he currently teaches at the Rodchenko Art School.

Using the tools of provocation and relentless observation of the everyday, in his works Bratkov reveals absurdity and painfulness of our reality, which is perceived by the artist as a huge collage. Bratkov has shown his works in many important exhibitions including international biennials in São Paulo (2002), Manifesta-5 (2004), Venice (2003, 2007, 2011), Moscow (2005, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013, 2015). His major solo exhibitions took place in Fotomuseum in Winterthur in 2007 (Winterthur, Switzerland) and in the PinchukArtCentre in 2010 (Kyiv, Ukraine). In 2009, he was awarded the main Russian State Prize Innovation for the work of visual arts for his installation Balaclava Drive.

Tatiana Kochubinska is an independent curator, writer and lecturer based in Kyiv. Her main expertise is Ukrainian contemporary art. In 2016–2019 she curated the Research Platform of the PinchukArtCentre, where she was engaged in curating, research and publication programmes. She edited the book PARCOMMUNE. Place. Community. Phenomenon devoted to Kyiv squatting group. In her curatorial practice, Tatiana deals with questions of responsibilities, memory, and trauma, connecting the Soviet past with today’s society. This is reflected in a series of exhibitions such as Guilt (2016), Anonymous Society (2017), and Motherland on Fire (2017). She curated the PinchukArtCentre Prize in 2015 and 2018 and co-curated Future Generation Art Prize in 2019 and the FGAP@Venice as a collateral event of the 58th Venice Biennale. In 2020 she co-curated Almost There online exhibition within the British Council project Museum Without Walls.

*Cover photo: Sergey Bratkov, We are not here, 2018. Neon, plastic pallet. Courtesy of the artist.

[1] He means the first large-scale personal exhibition of Sergey Bratkov in Ukraine, titled Ukraine and exhibited at the PinchukArtCentre between 23 January and 21 March 2010.

[2] Viktor Yanukovych was the president of Ukraine between 25 February 2010, and 22 February 2014. He was born in Yenakievo in the Donetsk Region (Donbas). His core sphere of influence, support, businesses, and voter base were linked to Donbas.

[3] Sergey Zarva is a Ukrainian artist. He has participated in many joint exhibitions with Sergey Bratkov. After the revolutionary events of 2013–14, he moved to Crimea because of his political views, and then moved to Russia.

[4] Ilia Isupov is a Ukrainian artist, a friend of Sergey Bratkov.

[5] He means the MANIFESTA 10, which took place between 28 June and 31 October 2014, at the State Hermitage, Saint Petersburg, Russia. Boris Mikhailov showed his series The Theater of War, Second Act, Time Out, December 2013 there.

[6] The Fast Reaction Group was an art group in Kharkov in the period between 1994 and 1997. Its members included Sergey Bratkov, Boris Mikhailov and Sergey Solonsky (with the involvement of Vita Mikhailova). The group’s main activities were provocative actions in public spaces which resonated with the relevant socio-political agenda.

[7] Innovation is a Russian government prize in contemporary art. In 2009, Sergey Bratkov won the main prize for his video installation The Balaclava Drive (2009).