Ahmed Cherkaoui, Autoportret we łzach (1961). W kolekcji Nourdine Cherkaoui.

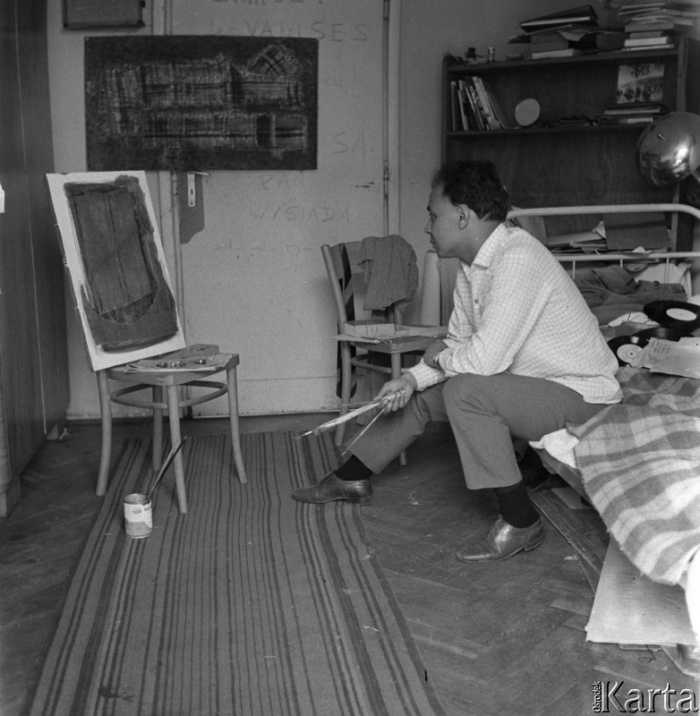

Between October 1960 and July 1961, the Moroccan artist Ahmed Cherkaoui stayed in Warsaw on a residency at the Academy of Fine Arts’ Faculty of Graphic Arts, where his instructors were Henryk Tomaszewski and Józef Mroszczak. Cherkaoui qualified for the residency funded by the Moroccan Labour Union (Union Marocaine du Travail, UMT) through the intercession of the UMT secretary, Mahjoub Ben-Seddik, an influential politician and economist. He was the first artist from the independent Kingdom of Moroccoto attend a residency programme at a Polish art school.1

From the beginning of his stay in Poland, Cherkaoui established close contacts with the older generation of recognized Polish painters, notably those associated with the Gallery Krzywe Koło: Henryk Stażewski, Alfred Lenica, and Erna Rosenstein, as well as with Irena Jarosińska, a photographer who covered the Warsaw art scene.2 It was likely through those contacts that he was able to present his art in a solo show at the Gallery Krzywe Koło in June 1961. All the featured works had been made during his Warsaw residency.

Ahmed Cherkaoui emerged as a pioneer of avant-garde art in post-colonial Maghreb, and the Warsaw period is widely considered as a breakthrough in his career.3 The French poet and art critic, Jean Clarence Lambert, wrote, “His real entry in modern art happened in Warsaw.”4 Toni Maraini, in turn, stressed, “In 1961 Cherkaoui came to Poland for a year to study at the Warsaw Academy. It was a decisive period in the evolution of his painting”5 Both Lambert and Maraini pointed in their publications to a criss-crossing of diverse influences and inspirations that defined the Moroccan artist’s work after his return from Poland. From 1961 onward, in his art could be found references to traditional Berber culture and Islamic religious motifs as well as to the avant-garde experiments of French, Polish, or German artists.

“Between the Maghreb, Poland and France he belonged to the immemorial Berber Morocco and the Paris of pictorial abstraction. To the Sufism of al Hallaj and Bisserian poetics in Southern France. To Stazewskian constructicism in Warsaw and to Boujad female tattoos.”6 wrote Jean Clarence Lambert in the catalogue essay Cherkaoui. My Friend, My Brother. The combination of all those highly diverse attitudes, trends, and styles allowed Cherkaoui to develop an innovative language that integrated matter painting and abstract art with the Maghreb cultural traditions. A special issue of the literary magazine Souffles, titled “Situation of the Visual Arts in Morocco” (no. 7-8, 1967), which discussed the independent Kingdom’s art of the previous decade, brought news of his sudden and premature death. In an essay devoted to Cherkaoui, Toni Maraini called his oeuvre an important historical fact, suggesting that his painting would be duly recognized only by the coming generations.7 From the moment of completing his art studies in Paris to his sudden death, Cherkaoui was active as an artist for eight years only (1959-1967). Consequently, the early Warsaw period was one when his experiments crystallized.

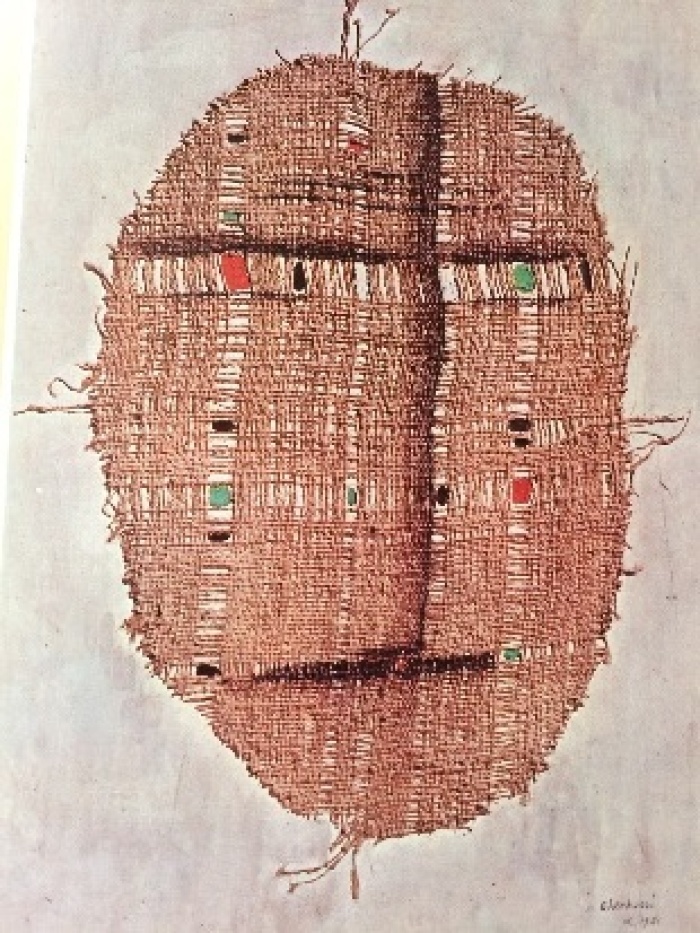

In this essay, I will take a closer look at the work Self-Portrait in Tears, which Ahmed Cherkaoui made and exhibited in Warsaw in 1961, and which alongside other works from the Warsaw period was reproduced in 1976 in the posthumously published book Ahmed Cherkaoui.8 I will discuss it in the context of his other experiments with jute fabric as well as reflecting on its significance among other works produced during the Warsaw residency and exhibited at Krzywe Koło. Taking into account the fact that it was probably the only self-portrait that he ever made, a closer examination of Self-Portrait in Tears will highlight distinct identity issues, inextricably connected with the ethnic culture of the Berber people. Recognizing the work’s significance will let us understand the evolution of Cherkaoui’s art, which after his return from Warsaw would be focused around motifs indicating his affiliation with the cultural and religious specificity of his native Morocco – in a synthesis of Berber signs and Islamic mysticism.

Portraits on Jute: Berber Woman (1960) and Self-Portrait in Tears (1961)

Since completing his studies at Paris art schools, Ahmed Cherkaoui remained heavily influenced by Roger Bissière and Jean René Bazaine, whose painting combined lyrical abstraction with fleeting impressions.9 During that time, the young Moroccan artist grew more and more interested in the material aspect of the painting. He was attracted by new trends of ‘matter’ painting of the 1950s,10 as well as by the art of Paul Klee, who several decades earlier started using jute in his representations of motifs inspired by non-European cultures.11

Upon arriving in Warsaw, the twenty-six-year-old Cherkaoui increasingly embraced new materials and textiles to make art in the vein of abstract impressionism. All his paintings of the Warsaw period were executed on jute that was taped or glued onto canvas, paper, or board. He painted geometric patterns on the jute, whereas the colours of the background always reflected a certain mood and ephemeral, fleeting impressions. The works’ titles referenced Warsaw townscapes, theatre shows, songs, and the artist’s own emotional experiences. Reflection, May Flowers, Self-Portrait in Tears, Variety, Incomplete, Warsaw by Night, Points, Love of Three Oranges, Blue Mask, Nocturne, Red Square, Warsaw those are titles that often suggested the abstract compositions should be interpreted in an intellectual, lyrical, and emotional manner.

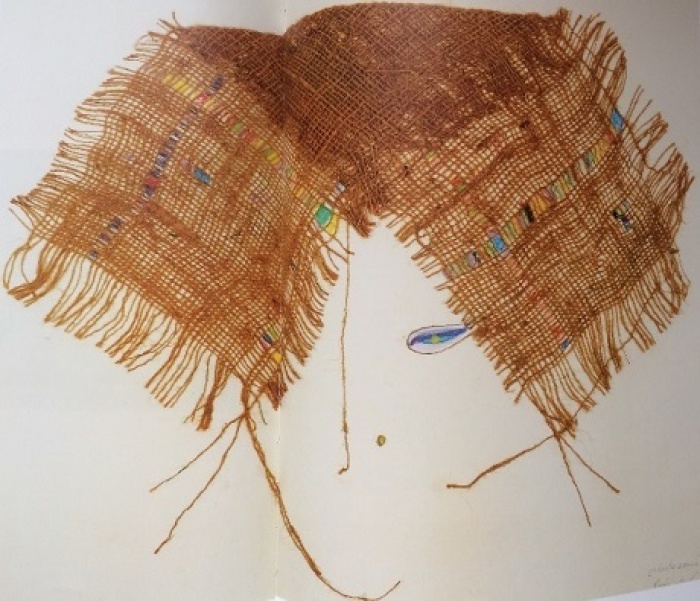

Most of Cherkaoui’s paintings on jute were non-figurative. An exception were two works, critically acclaimed today, where cut-out fabric was used to produce a portrait. Those were Berber Woman (1960) and Self-Portrait in Tears (1961). The former was produced in June 1960 in Paris, three months before the artist’s arrival in Warsaw. Jute fabric was pasted here onto a canvas painted white-grey in order to mark the shape of female hair, whereas threads emerging from the same fabric were rendered into fragments of the head portrayed: representations of one eye, nose, and oval forms of the face. Self-Portrait with Tears, in turn, executed in Warsaw, was a figuration that verged on abstract art. It represented the shape of a male head, the artist’s own, cut out in jute fabric, probably in natural size. Two horizontal lines and one vertical, representing the eyebrows, mouth, and nose, were painted on the oval piece of jute that was glued onto a canvas painted white-grey. Three shapes were added where the jute structure was looser: a green circle, a red square, and a black rounded figure. These geometric forms were composed so as to suggest the eyes, nostrils, and trickling tears. Were the horizontal lines slightly more rounded, they would depict the Berber sign of the “i-Mazigh-en man,” the culture’s best known symbol of the human figure and ethnic Berber culture.

Ahmed Cherkaoui, Berberka (1960), w kolekcji Mohameda Cherkaoui.

The two works presented, therefore, the portraits of a Berber woman and a Berber man using the same material, painted in different colours on the same white-grey background. Cut out in jute, the two head shapes were different, but complemented each other, comprising an image of the ethnic group of Berbers of both genders. Due to its oval shape, Self-Portrait with Tears approximated the form of a mask and clearly suggested that identity issues, bound up with the native culture of the people of the Maghreb region, meaning not only Morocco, but also Algeria, Libya, and Tunisia, were increasingly coming to the fore in his art. Cherkaoui was born in the city of Boujad and spent his childhood in Beni-Mellal at the foot of the Atlas mountains. His mother came from a traditional Berber family, and his childhood memories of the signs she wore as tattoos would become a key motif recurring throughout his work after 1961.12

It needs to be stressed that in 1960-1961, when Cherkaoui made Berber Woman and Self-Portrait in Tears, there were political tensions in Morocco between Arab nationalists from the influential Istiqlal party and ethnic Berbers of the Mouvement Populaire. During the reign of king Mohammed V (1956-1960) and initially during that of his son, Hassan II, who ascended to the throne in 1961, the identity of Morocco was presented mainly as Arab, whereas Berber culture was highly appreciated, but treated unequally.13 In light of this, the Warsaw-made Self-Portrait in Tears emphasized Cherkaoui’s identity rather as a member of the Berber people. In a preserved sketchbook, started in Warsaw on 7 May 1961, Cherkaoui intensely sketched new works revolving around Berber symbolism.14 Those sketches demonstrate that already then he was preparing to execute a whole series of works inspired by traditional Berber signs, which would define the course of his artistic experiments upon his return from the Warsaw residency. He produced the first painting in this style in Poland, exhibiting it at the Krzywe Koło Gallery in June 1961.

Self-Portrait with Tears at Krzywe Koło (June 1961)

The history of the Warsaw sketchbook, dated for May 1961, begins a month before the launch of Cherkaoui’s solo show at the Gallery Krzywe Koło. That venue was a place where from the mid-1950s through the mid-1960s young and established artists from Poland and abroad explored the status of the image, the process of the undoing of traditional painterly form, and sought its new definition. Combining influences of ‘matter’ painting with the approaches of abstract art, Cherkaoui’s paintings on jute resonated closely with the profile of the gallery, which was run by the artist and curator Marian Bogusz.

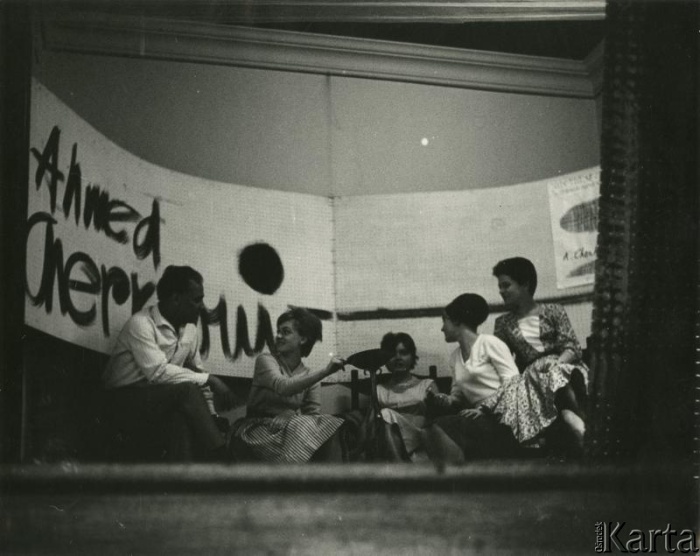

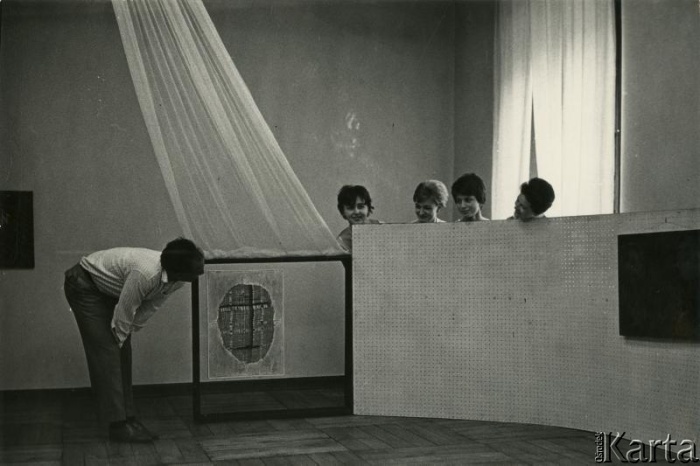

Wystawa Ahmeda Cherkaoui w Galerii Krzywe Koło (czerwiec 1961). Zdjęcie: Irena Jarosińska, (c) Ośrodek KARTA.

Wystawa Ahmeda Cherkaoui w Galerii Krzywe Koło (czerwiec 1961). Zdjęcie: Irena Jarosińska, (c) Ośrodek KARTA.

Cherkaoui’s exhibition probably didn’t have a catalogue, but preserved photographs taken by Irena Jarosińska make it possible to identify some of the works featured.15 The show’s leitmotifs included abstract “Warsaw impressions” on jute as well as Self-Portrait in Tears, which was displayed in the centre of the gallery space. Rather than being hung on a wall, it was mounted on a square frame positioned on the floor. It was around this piece that Jarosińska took most of the pictures. We can see, for example, three women who have knelt down on the floor around the piece as if they were posing with the artist himself, reduced here to the image of a Berber mask. Another photograph shows Cherkaoui in person, leaning over Self-Portrait to indicate that it is an image of himself. Women hidden behind other works smile at him, their curiosity obviously piqued by his personality and otherness, which was doubtless enhanced by the Berber Self-Portrait in Tears. It is worth mentioning that this is a portrait of the artist in a completely different emotional state, filled with despair. Paradoxically, as Jarosińska’s pictures show, the piece, which functioned like his alter ego in the gallery space, elicited smiles rather than arousing sadness. This is evident in yet another photograph, showing Cherkaoui next to it with a broad smile on his face. Moreover, Self-Portrait with Tears was the only figural work in the show as opposed to the distinctly abstract “Warsaw impressions.” The exhibition, therefore, presented an emotional self-portrait of a member of the Berber ethnic group, surrounded by visualizations of the feelings he experienced in the Polish capital. Together with Berber Woman, Self-Portrait in Tears attested to Cherkaoui’s affiliation with the Berber ethnic group and his need to emphasize the significance of the Maghreb’s native culture for a new Moroccan national art that he was envisaging.

In the context of Arabization policies pursued by the Moroccan authorities from 1956, Cherkaoui in the early 1960s deliberately emphasized his Berber roots. This changed when he returned to France and then went on a Unesco-funded residency to Morocco. From the on he focused on exploring not only Berber signs, but also the art of calligraphy and other nonrepresentational Islamic motifs, characteristic for transnational Arab culture. In the mid-1960s, he also painted several portraits of his wife Ludmila and son Nourdine in a style that blended abstract impressionism with calligraphy and Berber signs. Those works were different from Self-Portrait in Tears. The latter was unique in that, among other things, it was probably Cherkaoui’s last figural work. He had probably realized that the new art of independent Morocco should be a synthesis of Berber signs, the Arabic tradition of Islam, and new trends of European avant-garde painting. That was a course he embarked on in 1962, and it made him a true pioneer of Moroccan avant-garde abstract art.

Ahmed Cherkaoui obok Autoportretu we łzach w Galerii Krzywe Koło w towarzystwie czterech kobiet (czerwiec 1961). Zdjęcie: Irena Jarosińska, (c) Ośrodek KARTA.

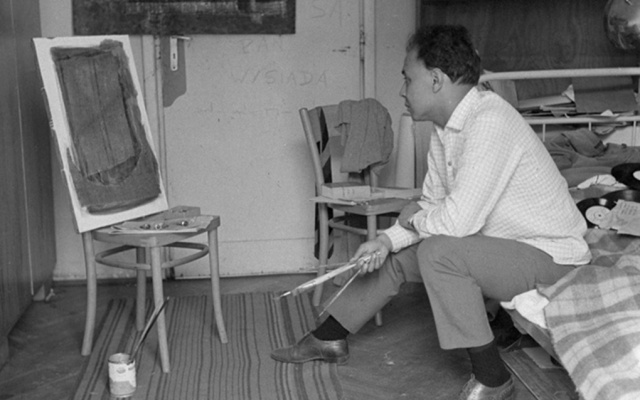

Ahmed Cherkaoui (1960-1961). Zdjęcie: Irena Jarosińska, (c) Ośrodek KARTA.

Translated from Polish by Marcin Wawrzyńczak

BIO

Przemysław Strożek – assistant professor at the Art Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences (PAN), his research areas include Italian futurism, Polish avant-garde, the foundations of global modernism and contemporary art. A Fulbright scholar at the University of Georgia (Athens, GA), the Israel Academy of Sciences (Tel Aviv), and the Accademia dei Lincei (Rome) and a scholar of the Foundation for Polish Science and the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education in the category of Outstanding Young Researcher. Przemysław is the author of several dozen scientific articles, the first monograph on the reception of Italian futurism in Poland, „Marinetti i futuryzm w Polsce (1909–1939). Obecność — kontakty wydarzenia” (2012), and a book on German Dadaism, Nic, to znaczy wszystko. Interpretacje niemieckiego dada (2016). Currently, he is working on an exhibition on Polish-Moroccan artistic relations during the Cold War in the Zachęta National Gallery of Art.

* Cover photo: Ahmed Cherkaoui, 1961. Photo: Irena Jarosińska. (c) Ośrodek KARTA.

[1] The subsequent residencies of Moroccan students, Mustapha Hafid and Azzedine Douieb, at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts were regulated by a special resolution No. 168/61 of the Council of Ministers’ Economic Committee, dated 9 May 1961, which provided for an increased intake of foreign students to Polish universities. Cf. Mustapha Hafid’s personal file, no. 94/2416, Archive of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw.

[2] Attesting to Ahmed Cherkaoui’s contacts with artists associated with the Gallery Krzywe Koło are photographs taken by Irena Jarosińska, kept in her archive at Ośrodek KARTA.

[3] Cf. the biographical essays featured in the three most comprehensive publications devoted to his work: Ahmed Cherkaoui. Textes par E.A. El Maleh, A. Khatibi, T. Maraini (Casablanca, 1976); B. Alaoui, ed., Ahmed Cherkaoui. La Passion du signe, exh. cat. (Paris: Institute du Monde Arabe, 1996); B. Alaoui, ed., Ahmed Cherkaoui. Entre Modernite et Enracinement, exh. cat. (Rabat: Musée Mohammed VI Art Moderne et Contemporain, 2018).

[4] Jean-Clarence Lambert, “Cherkaoui. Mon Ami, mon frere / Cherkaoui. My friend, my brother,” in Ahmed Cherkaoui. La Passion du signe, op. cit., p. 169.

[5] Toni Maraini, “Ahmed Cherkaoui – an analysis of his painting,” in: Ahmed Cherkaoui. Textes…, op. cit., p. 120-121.

[6] Jean-Clarence Lambert, “Cherkaoui. Mon Ami, mon frere,” op. cit.

[7] Toni Maraini, “Note sur l’oeuvre d’Ahmed Cherkaoui,” Souffles, no. 7-8 (1967), p. 46-47.

[8] According to the artist’s family, Self-Portait in Tears has been exhibited only once to date, in Warsaw in 1961.

[9] Jean-Clarence Lambert, “Cherkaoui. Mon Ami, mon frere,” op. cit.

[10] On matter painting in Europe and Poland, cf. Piotr Majewski, Malarstwo materii w Polsce jako formuła „nowoczesności” (Lublin, 2006).

[11] Representations of masks on jute were already made in the 1930s by Paul Klee, and Cherkaoui’s works seem to have been inspired by those rather than by contemporary uses of the material in arte povera.

[12] On Cherkaoui’s work and his associations with Berber calligraphy and signs, cf. Edmond Amran El Maleh, “Ahmed Cherkaoui,” in Ahmed Cherkaoui. Textes…, op. cit., p. 78-99.

[13] Cf. B. Maddy-Weitzman, The Berber Identity Movement and the Challenge to North African States (Austin 2011), p. 89-90.

[14] Ahmed Cherkaoui’s sketchbook is kept in the artist’s family archive. I hereby thank his son, Nourdine Cherkaoui, for making its contents available to me.

[15] The photographs are kept in the artist’s family archive, as well as in Irena Jarosińska’s archive at Ośrodek KARTA.