How do artists express solidarity with asylum seekers? By making use of their own tools as artists. Some solidarity initiatives in Europe, such as Trampoline House in Copenhagen or New Neighborhood in Berlin, have started by organizing art workshops in refugee shelters. In this interview, artist Marina Naprushkina describes how an art studio in the accommodation center in Berlin-Moabit developed into a large-scale community space.

Marina Naprushkina is the co-founder of the New Neighborhood (Neue Nachbarschaft) community center in Berlin that was established 2013 in order to welcome refugees. In its activities New Neighborhood uses methods based on art and culture. New Neighborhood differs from many “Refugees welcome!” initiatives because it is not conceptualized as a project that provides help, but as a site for mutual learning.

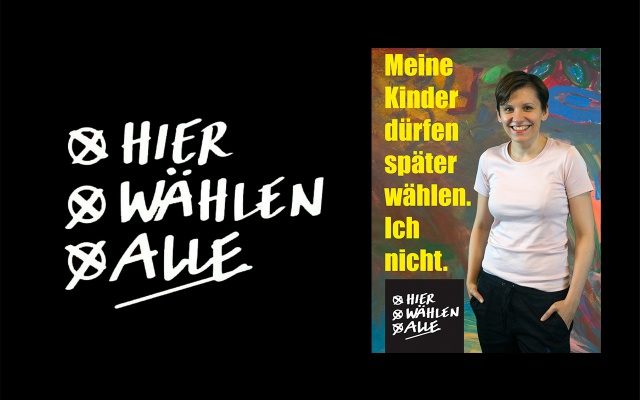

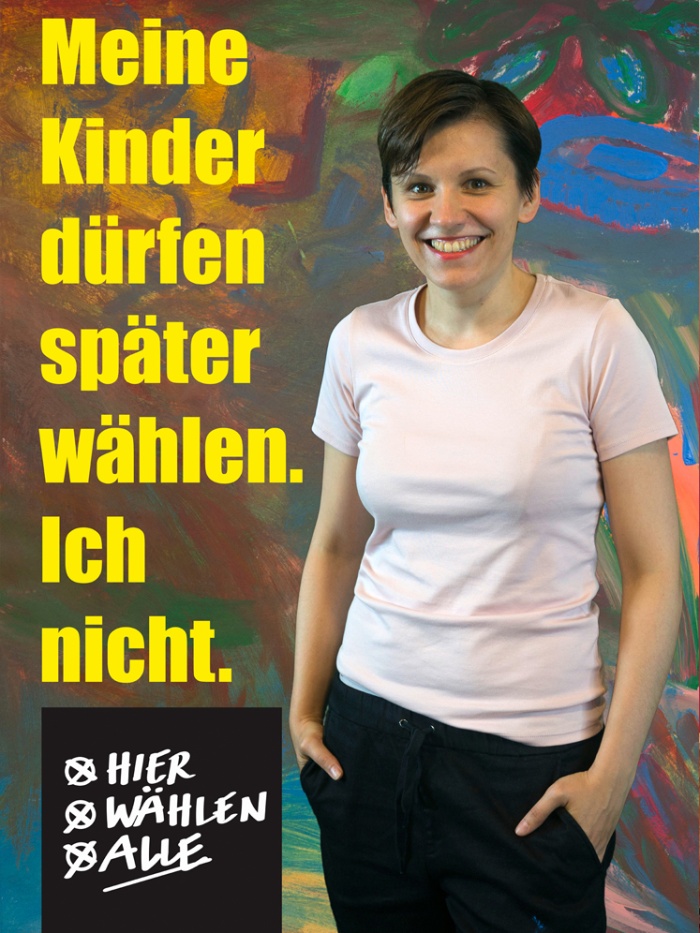

Plakat z serii "Hier wählen alle" stworzony przez New Neue Nachbarschaft przed wyborami do parlamentu niemieckiego w 2017 roku. Plakat przedstawia Marinę Napruszkinę. Napis głosi: "Moje dzieci będą miały w przyszłości prawo głosować. Ja nie."

Airi Triisberg: How did the New Neighborhood begin?

Marina Naprushkina: There were two factors involved. First, one of the first refugee shelters in Germany opened in Moabit in the summer of 2013, almost at my doorstep. Second, I happened to attend an asylum procedure in an administrative court. These procedures are open to the public, anyone can attend them, but at the time no one did. Back then, the public didn’t know much about these issues.

My art projects are usually developed not in an exhibition space, but out there, with the people. The decision to deal with refugee-related issues came naturally. I had a production budget for an exhibition in Stuttgart that I was working on. I talked to the curator and told her that I was going to open a studio in a refugee shelter. That’s how it began. No long-term activities were planned, it was a direct response. I was there, I met the people and realized that action was needed. I started to visit the shelter every day and soon understood that I couldn’t make it all by myself – the demand was huge. After a few weeks we were already a small group, working on the future programming of our community center.

How did the studio evolve into an independent space?

We came to the refugee shelter five times a week and organized various activities there. We had to leave because we came into conflict with the operators of the shelter. It was run as a private company and we revealed the poor conditions for its residents – there was no hot water in the showers, the rooms were overcrowded, not everyone was allowed to cook, the toilets were closed, children couldn’t play in the courtyard, etc. In spite of that, the company received state financing and made a lot of money. We turned this into a political case – as a result, the ministry started visiting the shelters and verifying whether contractual provisions were observed. Later we received a ban from the company and couldn’t organize any activities in the shelter anymore. We had to find a solution, so we talked to the operators of another space in the neighborhood and organized our events there. In the spring of 2015, we decided to look for a space that we could call our own. This turned out to be just the right decision. The space is big but was in terrible condition when we moved in – it had been unused for ten years. We renovated it together. Already at that point around 100 people were actively involved in our initiative. Some of them asked why we needed such a big space, but in the summer of 2015 refugees from Syria came. We started organizing events when the construction work were still ongoing. We were lucky, because when the people came in the summer of 2015, we were ready.

What is the conception of this space?

In 2015, numerous refugee support initiatives were launched. Today, many of them don’t exist anymore. If someone claims, “We will help refugees,” this isn’t an approach that will work for a long-term cooperation. We made a clear decision – we are not there to help. We do not work for refugees but with refugees. We also decided to stay independent. We don’t want any state subsidies in order to maintain a critical stance, continue our political engagement, and respond quickly. This wouldn’t be possible with project grants. Moreover, we want art to play a key role. We employ many different formats. I don’t want to call them projects because a project is something that has a clear-cut beginning and end. What we offer are ideas that we develop and continue as long as the people are interested.

We run an alternative art school and offer a broad range of cultural events. It is important to mention that we also became a culture production company. We would like to bring together professionals and amateurs during the production process, because we think this exchange is crucial for both sides. All our formats are as accessible as possible, so that anyone can participate. If people think they don’t know what art is, we can show them that they, too, can make art and we encourage them to do so. We employ art to empower people to speak for themselves. Statistically, the voice of refugees is never heard, someone always speaks on their behalf. No matter if the statements are positive or negative – refugees are always represented by another person. We want to change this power dynamic. Art offers powerful tools, because artistic formats come across faster and have an immediate social effect.

Can you name some examples?

One of our principal events is the German meet-up series (Deutsch-Stammtisch) that we have been organizing for five years which began in the first months of our initiative. This is not a typical German course with lecture-style teaching, but conversation groups led by more advanced German speakers. The purpose is to learn German, but of course much more can happen during our meet-ups – people can get to know each other. Our artistic formats are also very important, because they have a lasting effect.

On top of that, we run a publishing house and produce our own publications together with children and adults. They create their own pictures and texts, all of which are bilingual. We also organize events, always well-attended, to present and promote our publications.

This year, to name another example, we organized literary evenings. Refugees would never attend a reading in one of the so-called literature houses – they face too many barriers. They also wouldn’t go to an art exhibition in a museum. Cultural spaces are very elitist. At our events, we put everybody on equal footing and are never aloof. We invite authors who also perform at the International Literature Festival in Berlin. “Our” refugees come, the events are translated into several languages, people ask questions, there is always a lot going on.

Last summer we produced posters and put them up all around Berlin. Before the parliamentary election we ran a polling station where everybody could vote and we generated a lot of publicity. In Germany there are 10 million residents without German citizenship and, therefore, without the right to vote. We want to raise awareness of the fact that voting rights, attached to a particular nationality, are obsolete today. We carry out various actions that we present at our community center and through social media. This allows us to reach a lot of people – certainly more than we could approach with an exhibition.

Translated from German by Paweł Wasilewski

BIO

Marina Naprushkina (born in 1981, Minsk) is a political feminist artist and activist. Her diverse artistic practice includes video, performance, drawings, installation, and text. Her work engages with current political and social issues. Naprushkinaworks outside of institutional spaces, in cooperation with people, communities, and activist organizations. She focuses on creating new formats, structures, and organizations based on self-organization overlap in theory and practice.

Airi Triisberg is an independent curator, writer, and educator based in Tallinn. She is interested in the overlapping fields between political activism and contemporary art practices, issues related to gender and sexualities, illness/health and dis/abilities, self-organization and collective care practices, struggles against precarious working conditions in the art field and beyond. Her practice as a politicized art worker is often located at the intersection of political education, self-organization, and knowledge production. One of her ongoing research interests is focused on historical and contemporary moments when the experiences of living with illness or disability have been politicized in order to express social critique. In 2015, she curated Get Well Soon!, an exhibition presenting artistic rearticulations of social imaginaries rooted in the radical movements of the 1970s. Another strand in her practice has been focused on precarious labor and art workers organizing. In 2010–2012, she was an active member in the art workers movement in Tallinn. In 2015, she co-published the book Art Workers – Material Conditions and Labour Struggles in Contemporary Art Practice together with Minna Henriksson and Erik Krikortz. Currently she is engaged with anti-racist organizing work.