If the state of the art world is one of permanent war, then hospitality is used as an illusion to perpetuate existing conditions, while we, the art workers, flatter ourselves with the idea that we are making continuous progress within curatorial discourse towards artificial perpetual peace by practicing hospitality.

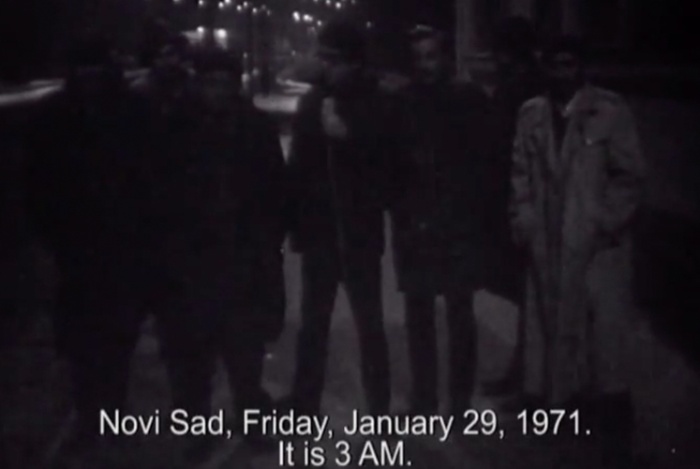

An example of radical hospitality can be found in Black Film (1971) by director Želimir Žilnik who picked up ten unemployed (and therefore homeless) men from the streets and brought them back to his apartment, to help “solve their homeless problem.” Back then, to imagine and create a radically different future, by means of hospitality, was still a possibility.

Hospitality is manifested in practice by hosting curators, artists, and audiences in at least two philosophical interpretations of the concept: while Immanuel Kant’s universal hospitality is still applicable, Jacques Derrida’s radical hospitality1 seems to be a bit too much for the surge of populism.

Kadr z filmu Black Film w reżyserii Želimira Žilnika (1971).

Kadr z filmu Black Film w reżyserii Želimira Žilnika (1971).

It was still possible at the Cultures of the Curatorial conference: Hospitality: Hosting Relations in Exhibitions at the Academy of Visual Arts in Leipzig, back in 2012. That possibility emerged from a transdisciplinary approach to curating that allowed for the plural use of this very term.2 Whatever is the implication of the curatorial, an act of hospitality should never be fetishized. The abuse of hospitality, as a form of institutional critique, is mainly manifested in a way that keeps (any non-hegemonic) Others at a distance, by appropriating and thus neutralizing their potential. Through a critical lens the hospitality in the art world perpetuates the existing power conditions and reinforces “the axis of the unloved.”3 Be it by making the art world seem relevant, empowered, and coherent – or by using art for the purposes of a much larger capital flow – such is the role of art and art residencies in the act of “creative placemaking” that directly boosts the real estate market4 hospitality gestures redistribute the structures in which power is/was exerted.

Add to that a dominant populist agenda, pessimist international politics in a time of anxiety and the decline of the critical aspect of the curatorial,5 the cultural turn that implies the constant necessity for navigation, or Mark Fisher’s impossibility of a society imagining a future different than the present – hospitality gestures are driven today by a horizonless orientation.6

If the art world reality is conditioned by boosterism and branding, then not only could the urge for universalism be erased but, due to profit maximization, radical gestures can be brutally forgotten.

Examples from the history of exhibitions

In the history of curating, the anthropological turn has been manifested through the practice of “curators-as-ethnographers” who have framed a transcultural worldview with their exhibitions, although in most instances, they have reinforced the Otherness perceived through a Western aesthetic (politicized) gaze.7

Since the Primitivism exhibition at MOMA (1989), Magiciens de la terre at the Centre George Pompidou (1989),8 and the Whitney Biennial (1993) numerous attempts have been made to use hospitality, for better or for worse, to expand or reconfirm, the hegemonic discourse of contemporary art. However, although these and similar exhibitions expanded the geopolitics of the curatorial, they preserved its hegemonic character by integrating the non-Western, non-white art worlds in a manner that does not resonate with colonialism and is not driven by projections of the exoticized Other. A rare occurrence was the positive outcome of hospitality in exhibitions such as the first Gwangju Biennale Beyond the Borders (1995) that “conveyed messages of global citizenship that transcend divisions between ideologies, territories, religion, race, culture, humanity, and the arts.”9

Katalog wystawy Magiciens de la Terre, Jean-Huber Martin, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paryż, 1989.

One example of non-geopolitical hospitality in exhibition making is curator’s Massimiliano Gioni’s exhibition “A Guest + A Host = A Ghost” at the Deste Foundation, Athens, in 2009. The overall work appeared to be a compilation of solo displays by specific artists, each of which was represented in the collection by many works. According to Gioni, “the creations by other artists have been placed within these ‘sub-groups,’ hence creating parasitic relations between the exhibits.”10

An attempt at a universal interpretation of curatorial hospitality is the 9th Istanbul Biennial’s “Hospitality Zone,” housed in a former warehouse that Charles Esche and Vasif Kortun had been given over to local artists’ initiatives, a gesture that, according to some, felt strategic rather than heartfelt because the zone was positioned as an antidote to the newly opened Istanbul Modern museum next door.11

Later on, as a director of the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, Charles Esche, explained that he was inspired by the director Želimir Žilnik’s radical hospitality that became Museum’s core value. Inspired by Derrida, Esche encourages the institution “to hand the keys over, to just say yes to what comes along, to say yes before knowing what is going to happen, before determination, anticipation, identification.”12

Wydok wystawy A Guest + A Host = A Ghost, kurator: Massimiliano Gioni, DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art, 2009. Zdjęcie: régine debatty. Źródło: Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0.

(Un)Spoken Abuse of Hospitality

The abuse of hospitality becomes transparent when it reaches an extreme, even more so than when it is the subject of critical examination. Take, for example, Manifesta 8 in Murcia, Spain, whose geographical location was ostensibly chosen to expand the Western art world into the Arab world and the African continent. Thierry Geoffroy Le Colonel, an artist performing institutional critique, hopped on the bus during the Manifesta 8 preview days and asked the people inside how many of them were from the Arab world or the African continent. It turned out that only one person on the bus was of Arab origin, and even she was based in the West.

Another extreme situation came about during the documenta (13) seminar in Cairo. According to Angela Harutyunyan, one female student asked to have all the cameras and microphones switched off before she would utter a word.13 For the student, it was not the content of the speech, the linguistic barrier, or the elitist jargon that created a wall between the various segments of the “audience,” the keynote speakers, or the students, but rather, it was the means through which the event was staged, including the technical equipment that turns such an event into a seemingly harmless convention. By asking for the technical apparatuses to be turned off, she seemed to demand change of both the very conditions upon which the speeches were produced and the manner in which the event was staged.14

Documenta 14 was a strange reversal of the roles of hosts and guests. It still depends on one’s interpretation if it was indeed Athens that hosted documenta 14, or if it was documenta 14 that invaded and hijacked Athens, in order to host (or colonize) Greece and further along the Mediterranean basin. That strange constellation reconfirmed the agonistic aspect of hospitality.

If the curatorial has borrowed the term “hospitality,” has it borrowed the best of it? As Kant noted in his essay “Perpetual Peace,” the state of peace among men living in close proximity is not the natural state (status naturalis).15 The natural state is one of war, which does not just consist of open hostilities, but also in the constant and enduring threat of them.16 Analogous to this, if the state of the art world is one of permanent war, then hospitality is used as an illusion to perpetuate existing conditions, while we, the art workers, flatter ourselves with the idea that we are making continuous progress within curatorial discourse towards artificial perpetual peace by practicing hospitality.

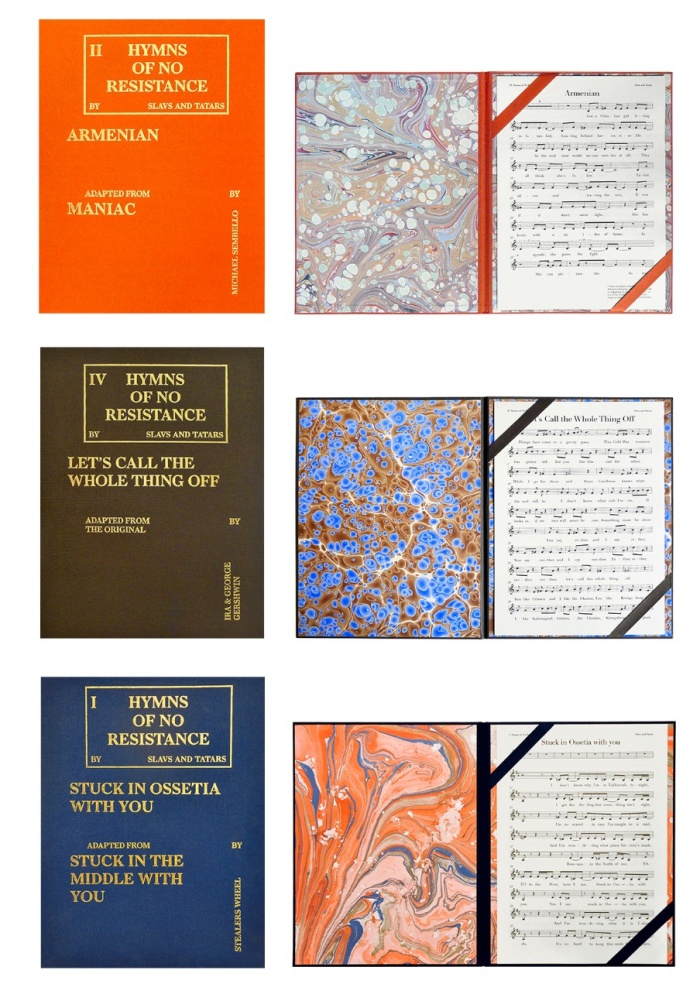

Slavs and Tatars, Hymns of No Resistance, 2010-2014, złota folia na płótnie, tradycyjny papier marmurkowy, druk laserowy, różne arkusze piosenek, 42 × 30 cm. Dzięki uprzejmości artystów.

If curatorial hospitality is operating in the realm of desire it is a gesture of curatorial simplification.17 If we agree that hospitality has been used in a way that has perpetuated the already historicized, sociopolitical art world then there is a need for a form of hospitality that is not based on pre-established relations but instead is examined through (ethical) issues and dilemmas. Instead of reproducing pre-existing relations hospitality would not use exhibitions as mere tools of cultural diplomacy.

It is most important to understand the abuse of the very term hospitality in the curatorial – the abuse of its active, productive aspect, which stems from the lack of a meta-position, which has not been achieved despite the numerous attempts to produce discursivity on hospitality and curating. Achieving such meta-positioning implies scanning the history of the implementation of hospitality in curating. Historically, in terms of the geopolitics of the curatorial, meta-positioning has been envisioned from the hosts’ point of view. However, instead of seeking to represent the history of curatorial hospitality, we have to try to figure out what is being neglected. Presuming that the social and political have already been historicized, a critical perception should be aware of if not break up the already institutionalized abusive social and political agendas.

Ideally, hospitality in the context of the anthropological turn in curating should be humanism on the move, which, according to Immanuel Kant, is a basis for cosmopolitanism.18 However, this hospitality is not to be implemented as a Western concept that ignores differences and is based on a Euro-Atlantic worldview. Humanism on the move should articulate the entire dynamics of the post-Other. It should not be articulated through the Western perspective, because even when geographical distance is overcome, psychological difference remains. Future hosts should be thinking in terms of the post-Other or, even more properly, in terms of the radically “unsame” of the ones who cannot be measured by known parameters in a constantly changing culturalscape.

How can guests be hosted when the very hosts would be under existential treat?

Moreover, it is the contradiction between sentiments manifested in the sense of affection (like attracts like) and a sense of duty, that are a treat when it comes to hospitality. For example, Alex Farquharson’s argument in his lecture “Institutional Mores” is grounded on the thesis “that curatorial practices that integrate social values such as generosity, curiosity, and hospitality through the curatorial concepts [...] within the institutions, are opening up the institutions by abandoning and exchanging the space of requests for the space of desire.”19 Later on, he argues that the unstructured space of desires is a way of reproducing the existing institutional order. If the unstructured space of desire is manifested through the affective flow of ideas about who should be hosted or not, then it leads towards the potential abuse of hospitality in curating. The real question is whose requests and whose desires are being considered? This is one that Esche asks indirectly when he reflects upon what capacities institutions can offer and whether an institution can encourage the guest (the Other) to ask questions that match the institutions’ resources.

Fast forward a bit less than a decade and certain rare institutional practices showed that the radical gestures and acts of hospitality had become embedded within the L’internationale20 network, that the Van Abbe Museum is a part of. Take for example, the radical gesture of hospitality at the Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova in Ljubljana, Slovenia where the coffee shop is run and managed by migrants.

In the exhibitions curated by curators as ethnographers, hospitality was used to reconfirm the mainland of the art world by keeping a potential enemy under control. On the contrary, performative radical gestures allow the guests to change this hierarchy into a heterarchy that would acknowledge multitude nodes and lines that will consequently redistribute the power.21

As one of their last projects at the Gallery Nova in Zagreb, before taking the directorship of Kunsthalle Wien, the WHW collective hosted the exhibition Želimir Žilnik: Shadow Citizen in late 2018.22 In their first interview after stepping into the directorship they announced that Kunsthalle Wien would aim to be a hospitable institution.23 Vienna was/is the gatekeeper for creating knowledge about the Balkans by means of hosting exhibitions. What will happen now when those who, by their origin represent the once hosted, became hosts in the city that aims and succeeds in generating profit by the means of arts and culture?

The act of hospitality (not just a small gesture) that Kunsthalle Lissabon performed for its 10th anniversary meant being hospitable within the known and appreciated way of critiquing what is not appreciated, namely the overwhelming touristification of Lisbon and its urban gentrification. Kunsthalle Lissabon let four international partners, four likeminded institutions take over the space, production, and communication infrastructures, resources and online presence that they’d left vacant. According to Kunsthalle Lissabon’s statement24 “It is as if each of these four institutions opened a pop-up version of themselves in Lisbon over a period of time.” Not being able to align themselves within the new urban currents of touristified Lisbon they have solidified their position by forging alliances with international institutions that they hold in high regard. By this use of curatorial hospitality, both their local and international agency became stronger in the art world. The unconditioned welcome became their answer to the conditioned reality. Time will tell if they have succeeded in producing a critique of gentrification or an act of institutional reinforcement.

Caroline Mesquita, Astray, instalacja. Marmur, ziemia, żelazo, tynk i wosk. Widok instalacji w Kunsthalle Lissabon, 2018. Zdjęcie: Bruno Lopes. Dzięki uprzejmości Kunsthalle Lissabon.

Caroline Mesquita, Astray, instalacja. Marmur, ziemia, żelazo, tynk i wosk. Widok instalacji w Kunsthalle Lissabon, 2018. Zdjęcie: Bruno Lopes. Dzięki uprzejmości Kunsthalle Lissabon.

While under Trump both racism and feminism re-emerged as urgent issues in the US, and while the Latin art worlds are still elusively inclined to the Euro-Atlantic axis, the problems of hosting the non-Western, non-white subject are augmented with the urge for hosting nonhuman, artificially intelligent others.

It is for time to tell how the roles of hosts and guests in the art world will be further reversed due to the change in climate currents. The adjustment of guests that were magnetized between the Unconditioned Ideal, that was backed up with a heartfelt welcome, and the Conditioned Reality performed by the laws and regulations of the residency, will be changed under the laws of nature. What will happen when the conditioned reality becomes so harsh under climate breakdown that the unconditioned ideal can no longer be performed. How can guests be hosted when the very hosts would be under existential treat?

Climate Crusader (Alexander Zastera) na tarasie Pérez Art Museum w Miami, 2019. Zdjęcie zrobione podczas IKT Congress, 2019: Exploring issues in resilience and sustainability in cultural production. Zdjęcie: Maja Ćirić. Dzięki uprzejmości autorki.

Meanwhile, art hospitality residencies follow the power flow and its regimes of hospitality25 that are never fully exhausted. Depending on if they are more universally or radically inclined, these regimes of hospitality will either encourage participation or secularization. For example, FRAME has just announced a Rehearsing Hospitalites program which is planned to run until 2023,26 thus pointing its institutional attitude towards a certain horizon. If this program acts in order to secure the citizenship as is, it will foster a form of a common and comfortable universal hospitality, approved by the gatekeepers according to the level of utility and tolerable politics. If it is a radically oriented regime, then it will increase the tolerance for participation of residents in real distress and who are in need of safety and worthy of encouragement.

After all, artist residencies are rare intellectual oases where it is possible to imagine a different society. The problem is at the intersection of the oasis and the desert, in the potential of thought to act.

BIO

Maja Ćirić is an independent curator and an art critic based in Belgrade, Serbia with experience in leading and contributing to international art projects. She has a PhD in Art Theory (Thesis: "Institutional Critique and Curating") from the University of Arts in Belgrade, Serbia. She was the curator of the Mediterranea Young Artists Biennale in Tirana, Albania, (2017), the curator (2007) and the commissioner (2013) of the Serbian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Her speaking engagments were, among others, for MAC VAL (2017), Centre Pompidou (2018), MNAC Bucharest (2018). She is a published author.

Her areas of expertise span from the geopolitics and the curatorial, through curating as institutional critique to the research of, and lecturing about, the methodology and epistemology of curating. Maja thinks about the art world in terms of criticality and post-globalism. She has a proven track record of spotting new artistic talents at the early stage of their careers.

She is a recipient of the Lazar Trifunović Award for Art Criticism (Belgrade), the CEC ArtsLink Independent Projects Award (New York), the ISCP Curator Award (New York), the ICI (Independent Curators International) and The Dedalus Foundation Curatorial Research Award (New York), Visual Artists Ireland Visiting Curator Award (Dublin).

*Cover photo: Caroline Mesquita, Astray, installation. Marble, earth, iron, plaster, and wax. Installation view in Kunsthalle Lissabon, 2018. Photo: Bruno Lopes. Courtesy of Kunsthalle Lissabon.

[1] Immanuel Kant, “Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch,” in Kant’s Political Writings, ed. Hans Reiss (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970), 93–130. Jacques Derrida, Of Hospitality: Anne Dufourmantelle Invites Jacques Derrida to Respond, trans. Rachel Bowlby (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000). For Derrida, in order to be hospitable, it is first necessary that one have the power to host, that is, have some kind of control over the people being hosted, which means that the guests will be under control: closed to boundaries, to nationalism, and even to the exclusion of particular groups. In Derrida’s possible conception of hospitality our well-intentioned conceptions of hospitality render the others. See the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “Possible and Impossible Aporias: b. Hospitality,” (accessed 2 December 2014), http://www.iep.utm.edu/derrida/#SH7b

[2] As a main topic of the Cultures of the Curatorial conference in Leipzig.

[3] Dambisa Moyo identifies “the axis of the unloved,” in other words, the regions around the world that have been bereft of investment, particularly from Western economies. This means Africa, and also countries in South America, such as Chile and Brazil, and in Eastern Europe, such as Russia and Kazakhstan. See “Dambisa Moyo says China is ahead of the curve in the race for the world’s resources,” Africa at LSE (blog),

http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2012/07/03/dambisa-moyo-says-china-is-ahead-of-the-curve-in-the-race-for-the-worlds-resources/ accessed 2 December 2014

[4] Todd Lanier Lester, Artist Safety Hosting: A Guide to History, Ethics & Practice, commissioned by Artistic Freedom Initiative, 2019.

[5] From Irit Rogoff, “From Criticism to Critique to Criticality,” eipcp.net. European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies (January 2003), http://eipcp.net/transversal/0806/rogoff1/en (accessed 08.11.2010). to Concerning the Curatorial to a Lecture by Irit Rogoff on Wednesday, 12.06.2019 at Aalto Arts. Factors were discussed that led to the establishment of the Curatorial / Knowledge program at Goldsmiths, University of London. The lecture will outline the program’s progression and transformations over the years, why it might have already fulfilled its aims and why – under current conditions – it does not seem as necessary as it once was. At stake here is the term “curatorial,” which does not seem capable of capturing a more contemporary understanding of the way we work now. This leads us to a presentation of a new project “The European Forum for Advanced Practices” in which such ways of working have been addressed and expressed in the term “advanced practices.” https://www.aalto.fi/en/events/concerning-the-curatorial-a-lecture-by-professor-irit-rogoff accessed 16 June 2019.

[6] Patricia Reed in The Task of Abstract Space, https://www.e-flux.com/video/268275/e-flux-journal-nbsp-and-harun-farocki-institut-present-art-after-culture-navigation-beyond-vision-at-haus-der-kulturen-der-welt-panel-two-nbsp-the-tasks-of-abstract-space-with-ramon-amaro-matteo-pasquinelli-patricia-reed-moderated-by-brian-kuan-wood/ accessed 15 May 2019.

[7] Paul O’Neill, The Culture of Curating and the Curating of Culture(s) (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 54–72.

[8] https://msu.edu/course/ha/491/mcevilleyartandotherness.pdf

[9] See the Gwangju Biennale website, accessed 15 October 2012, http://www.gwangjubiennale.org/eng/gb/past/intro/?no=1&mode=view&BN_IDX=50&p=1

[10] See Deste Foundation for Contemporary Art, “A Guest A Host = A Ghost,” accessed 2 October 2012, http://deste.gr/exhibition/guest-ghost-host

[11] Jörg Heisser, Erden Kosova, Jan Verwoert, “9th Istanbul Biennial: City Report,” frieze, no. 95 (November–December 2005), accessed 3 October 2012, http://www.frieze.com/issue/article/istanbul_city_report/ accessed 22 November 2014.

[12] Charles Esche, “Practicing Hospitality,” a panel discussion at Symposium: Of Hospitality, Smart Museum of Art, Chicago, 5 May 2012, see Vimeo, accessed 2 December 2014, http://vimeo.com/42269151

[13] Angela Harutyunyan, “On the Stage of The Event: The Cairo Seminar in Alexandria; dOCUMENTA (13),” Contemporary Visual Culture in North Africa and the Middle East, accessed August 2012, http://www.ibraaz.org/news/32.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Kant, “Perpetual Peace.”

[16] Ibid.

[17] Farquharson, “Institutional Mores.”

[18] “Cosmopolitan right shall be limited to conditions of universal hospitality.” Kant, “Perpetual Peace,” 329.

[19] Alex Farquharson, “Institutional Mores,” a paper given at the conference “Institutional Attitudes,” Brussels, April, 2010, see Vimeo, accessed 23 May 2012, http://vimeo.com/12206073.

[20] See more https://www.internationaleonline.org/about

[21] Rosalba Belmonte and Philip G. Cerny, Heterarchism: Toward Paradigm Shift in World Politics, paper presented at the interim conference of the International Political Science Association Research Committee No. 36 Political Power, Moscow 22–23 May 2019

[22] http://www.whw.hr/izlozbe/2018_izlozba1.html

[23] Interview: Collective WHW on their appointment as directors of Kunsthalle Wien,“We don’t expect an easy ride” by Klaus Speidel https://www.spikeartmagazine.com/en/articles/interview-collective-whw-their-appointment-directors-kunsthalle-wien?fbclid=IwAR1aos0Kjl77-fupWLeer68MxOZU798FXBQ2CqE1MjStR-A6kLdvn_GnmWg

[24] “Kunsthalle Lissabon will be the host that is so radical it gives everything it has to its guests, disappearing in the process. The notion of hospitality has always been one of the central pillars of our institutional thinking, and for the tenth anniversary we want to take it to the extreme. At the same time, we also want to investigate temporary disappearance as a way of reflecting on the cultural fabric of a city like Lisbon at the present time. We have no idea what the outcome of this whole process will be.”

[25] Christophe Foultier, Regimes of Hospitality, Urban Citizenship between Participation and Securitization – the Case of the Multiethnic French Banlieu, 2015

[26] https://frame-finland.fi/en/2019/06/07/save-the-date-gathering-for-rehearsing-hospitalities-in-helsinki/