This conversation took place as a public event in the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, Warsaw, 13 April 2017.

David Maroto: I wanted to ask you a few questions because I am very interested in your position as an editor, writer and curator. Perhaps we can start with 2HB, a magazine that supports artist’s fiction primarily and it’s published twice a year through the Centre for Contemporary Arts (CCA) Glasgow. My question is: how did this idea originate? Because you have been doing this a number of years, and it’s based on an open call I believe?

Francis McKee: Yeah, it arose from pressure. There are so many people in Glasgow, so many artists, who are practicing creative writing as part of their wider practice. I know them as students or I know them as artists in the city. So, with that amount of pressure there was nowhere for them to publish. So, we started the magazine, and had an open call, and since then we have always had a huge amount of submissions. And we select and publish from that. But the description is that it has to be writing within the context of visual art – creative writing. Because the first call, the first submission, we got short stories from Australia, we got novels from Venezuela, you know, they were just straight novels, straight short stories. So, we had to sort of say that this was to be within the context of visual art, with an awareness of visual art surrounding the writing and the practice.

And do you see something specific to this fiction written by visual artists? Something that would set them intrinsically and specifically apart from, say, fiction at large?

Yeah. As you were saying earlier, some of it would be bad novels. They would be like bad novels, not because they aren’t trying to write good novels but because they were trying to use the structure and template or the kind of elements of a novel or a short story to do something else. Therefore, it reads badly if you were expecting a short story. But they will use that formal and those structural elements; they are using those within some other context for some other end. And sometimes that’s simply a gesture. One that I remember most was a Chinese menu in Chinese from a Chinese restaurant in Glasgow. Not many people really understood that, but it was a gesture and it was a visual gesture within the book, within the context. It can be used in that way, I think.

Okay, because I am thinking that narrative fiction, in a way, is a suitable means to convey, for example, issues around subjective visions of the world. And there is this proliferation of artists’ novels, but also artists who write fiction, maybe in a short fiction form like in 2HB. As a result, some people speak of a current "narrative turn". I wonder what you think of that?

Some are. Some people are turning. [Laughter] And some people aren’t. But I think they are using literary devices. I think there is a certain narrative turn and that is very important, and it might be different than, say, a lot of the works you showed earlier like Leonora Carrington. These works are surreal and that’s not necessarily a narrative turn but more about a surreal perception of reality. And it’s easier in fiction to do that. I wrote my book because it’s easier to talk to the dead in a book than for me to talk to the dead in reality. They’re very quiet. [Laughter]

So, it’s easier to lie, basically. The whole setup is that it’s a lie, so you can lie happily within it and I think that’s part of it. For other people, it’s actually a structure where the words themselves become objects. There is a huge history of concrete poetry in Scotland as well. There are moments like that where there is no attempt to have a narrative, but simply almost fetishizing the word and the shape of the word and the look of the word. And there are other times when the words aren’t that important – they are transparent, but the narrative is important.

Before we were speculating that maybe this is an attempt to renew "art language". Meaning, on the one hand, we have this kind of exhaustion of a certain way of writing and reading about art. That’s one thing. On the other hand, some artists are not only using a text that is next to their work, but that text is the work in itself. Maybe we can divide this question in two, but what do you think of this? Because you are very engaged with writing fiction now, but you are also an art critic.

I’ve always written fiction better than art criticism. And quite often a lot of the people – say Douglas Gordon, Christine Borland, Pipilotti Rist, Matthew Barney – all said, Pipilotti Rist said, "Would you write a little book? Don’t write anything about the art, just write a book." And she let me write a book to go with the exhibition. So, it was about a character called Pipilotti Rist, but it wasn’t anything to do with the show and it wasn’t really Pipilotti Rist. It was incredibly generous, but I think she was also at a point where so many people had written about her work that she could take that chance in having someone not write about the work and write about the ideas around the work instead. I think they get fed up with good proper criticism sometimes. [Laughter]

This also feeds into the second part, which is that theory at the moment – the way artists write and the way critics write about art – is so depressingly bad and dead. I just want to rant now. But you know, theory, there is nothing wrong with theory, but it has become homogenous, incredibly predictable and incredibly divorced from reality or art. It’s so predictable that when you read it, you don’t actually have to wake up to read it anymore. It doesn’t connect to anything in reality anymore. We were talking earlier about the criticism being levelled at the show in Athens at the moment, at Documenta, where the criticism is so far removed from the reality of life in Athens, or even, the artworks in Athens, that it alienates both the population in Athens and the audience. It’s become too distant, and too predictable, and too polite, and too politically correct, and too sanitised and too clinically dead to actually communicate very much anymore.

But everyone is taught to write it in art schools, and artists are taught to speak it, and art writers are taught to write it, and life is too short to read it – and that’s the problem. It really doesn’t actually apply very much. I’ve got nothing against really good theory, but if it’s that divorced and the distance from reality has become that wide, it has very little relationship anymore. And I think that’s what’s happened: the art world is just like politicians and Brexit, or politicians in America, who go, "What happened?" Oh well, what happened is, you lost connection with reality so badly that you had no idea what was happening anymore. And that’s what’s happening with Documenta for instance, the relationship to reality or art has become so distanced that it no longer functions.

So, I think that’s one of the problems, and I think people turn to narrative as a result because it has a connection to reality. You describe someone walking down the street, you’re describing someone eating porridge. There is a relationship to reality that you have to accept. And you can place the theory within that and embody the theory within that. I think that’s what’s attracting a lot of people to narrative and to fiction, that it has to acknowledge and sort of confront reality, and then imbed the theory within reality; rather than live in a university where you never have to deal with that. So ... rant.

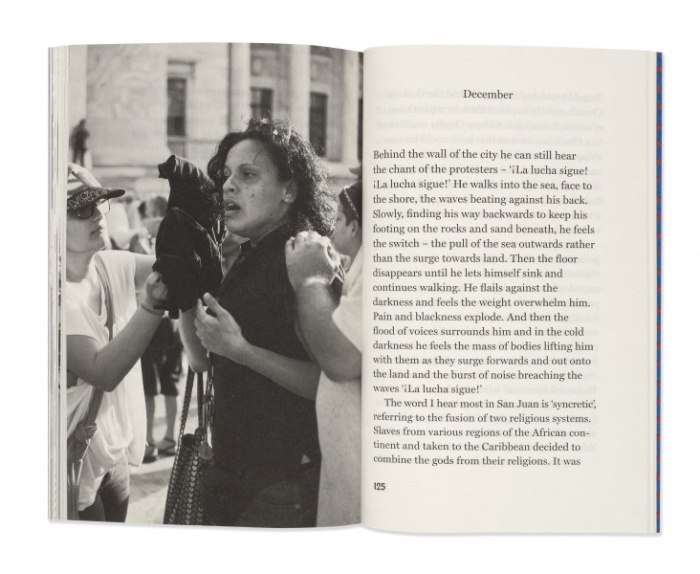

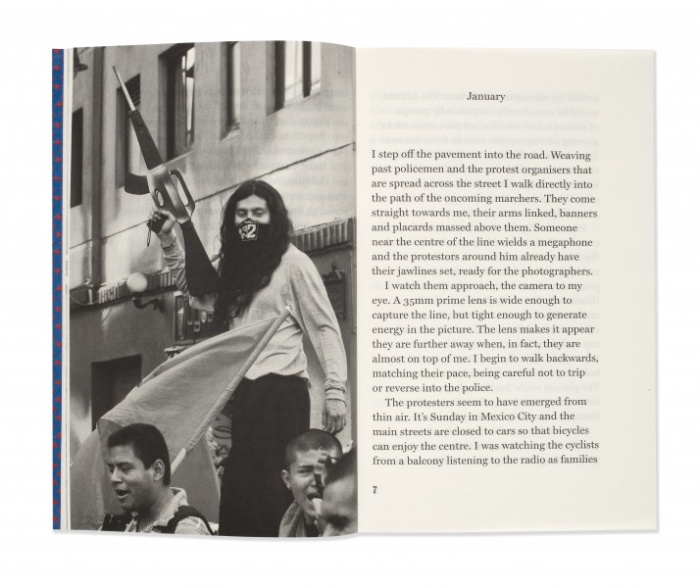

Strona z "Even the Dead Rise Up" autorstwa Francisa McKee. Dzięki uprzejmości Francisa McKee oraz Book Works.

Yeah, that’s something that I think very often. That art theory more readily engages with other theory before it engages with the reality of the work it is supposed to be analysing. Theory will always engage with any other previous theory by Foucault, Derrida, or Deluze and Guattari, and it hardly ever touches the reality of the work. In fact, many of these critical texts could be interchangeable and still they would work.

Yeah, you wouldn’t notice. [Laughter] And that’s why maybe the Hannah Black controversy around the Dana Schutz painting is so controversial. Not because of what she says, because it’s flawed, but because she actually addresses an artwork. God forbid you actually address an artwork and say, "I don’t like this work," or "This work works in such a way." Whereas you read Artforum and most criticism never dares to take on the work in any way. It just makes these general comments that slide off the work and slide off criticism in some way so that nothing is ever discussed, nothing is ever said, no one is ever criticised. You know, we all like or dislike various works. But you’re never going to read that in a magazine, you’re never going to read that in a catalogue. And a catalogue is particularly compromised.

So, I think a lot of those artists ask for fiction. Have you read a catalogue where someone goes, "This work just isn’t up to it. It’s not as good as the last work." Or, "This work’s crap but if you go to the last exhibition it’s good. But buy the last catalogue, this work’s shit." It just doesn’t happen. It’s immediately compromised. Everybody who writes in the catalogue is bound to say – it’s in the contract – that this is good work. It’s compromised criticism and we accept that, but we shouldn’t.

Let’s move now to your personal work, Even the Dead Rise Up. I’m not completely sure whether to call it a novel? But we can speak about it in a second. I was more interested in knowing your motivation to write, let’s call it for the time being a "novel" or a "novella". What’s your motivation to write it?

I’m not sure it’s a novel either. It wasn’t based on a novel – I actually ripped off an entire structure from another book, but no one has noticed yet. [Laughter] So I’m not saying until someone actually notices.

But it wasn’t a novel. It was based on New Journalism. And I’m really interested in New Journalism and looking at the world around you and describing that. I have been working as a documentary photographer and going to protests for three or four years now and documenting them. I went all last year to the Nuit debout protests in Paris every two or three weeks and photographed that non-stop. I’m interested in documentary photography and I then became interested in documentary writing within New Journalism in the 60s and 70s, and I wanted to steal from that. And that’s kind of what I did. So, I continue to wait to see if anyone notices. [Laughter]

It reads as a kind of essay under the guise of a novel. I mean it made me think of Chris Kraus in the first place. It made me think of fictocriticism. It made me think even of Fuck Seth Price, which uses some conventions of narrative fiction but, in reality, it’s very reflexive. I was wondering if you had that also in mind?

I did. You put that beautifully and I’m not that coherent! I read the first few chapters of Chris Kraus’ book, I Love Dick, and then I stopped. And I haven’t read Seth Price and I haven’t read many of the other people. But I thought I’d written a lot of essays. So, there were things I wanted to write, like the history of spiritualism or the ontology of photography, but I needed to write a narrative and I embedded them in the narrative because I’d thought about that idea of the distance between theory and reality being too far. I thought you could talk better about the ontology of photography if you’re actually describing examples in the text, within the narrative, that you can use as evidence. And you can see the dynamic I am talking about in people I am describing in the certain situation in the protest. And that made it much closer than me writing an essay on the ontology of photography. You can see that essay, "The Ontology of Photography on François Laruelle, blah, blah, blah ..." You know, you would never download it. You would never want it. So, if I sneak it in there you might read it. And then there is other stuff in there that is more interesting. It’s a smuggling operation in some ways, to get those theories in and to embody bits or to analyse the narrative itself. Because the narrative is about my life and protest. It’s about trying to analyse that through this fictional approach. It’s an odd mixture, but it’s definitely fiction and criticism.

Earlier you were telling me about some formal choices when the time came to design the book, really as an object, that I thought it might be interesting to say so now in front of the audience. Because the kind of graphic design choices you made would convey it visually as a Penguin paperback and therefore a novel. Or, maybe we should clarify first that you published this with Book Works, which is a publishing house specialising in artist’s writing.

I was lucky in that I wanted it to be more novelistic looking. I wanted it to be like a pocket book, nice and soft and you can stick it in your pocket and read it just like a ‘dying novel’ kind of notion. And they initially were hoping that it would be much more formal and maybe look more like an artist’s book. Partly because they are an artist’s book publisher and not a novel publisher and they want to maintain a distance between the two. But it was a very nice designer, a really beautiful couple, who designed the book. But they also realised there wasn’t enough money to make that formal separation. And because of that, the book got softer and the book got smaller, the book got more floppy and flexible. So, it gradually evolved into this novel feel and they eventually relented and went for that and began to see that this could be good and would still be far enough away.

And it’s got pictures. The pictures also make it look more "arty". So, it moved enough that we were both satisfied. I was quite satisfied that it’s just small and handy.

Who do you expect to be your readership? Because Even the Dead Rise Up is published by Book Works and, like I said, the readership is art world related people because they publish artist’s fiction, etc. Do you expect it to be read by this art crowd? Or who would be your ideal readership?

I think taxi drivers would be my ideal readership. Seriously. They did most of the work. So I would love it if they were, but in reality they won’t. But this also has to do with distribution systems. Book Works, Walther König Books, Corner House, all these publication distribution systems will distribute to bookshops like the one you have out here. There are art bookshops on that circuit. So, it will end up in those shops so the people who come to places like this will be the people who will buy it, but other shops won’t get it.

And my other book [How to Know What’s Really Happening] is on Amazon and it is selling in a weird way. It is selling to anybody because it’s so well disguised it looks like I actually know what’s happening, which I don’t. But I don’t want to spoil it for you! If you could get a different distribution I think other people would maybe pick it up, but maybe that’s a bit idealistic. They would be disappointed.

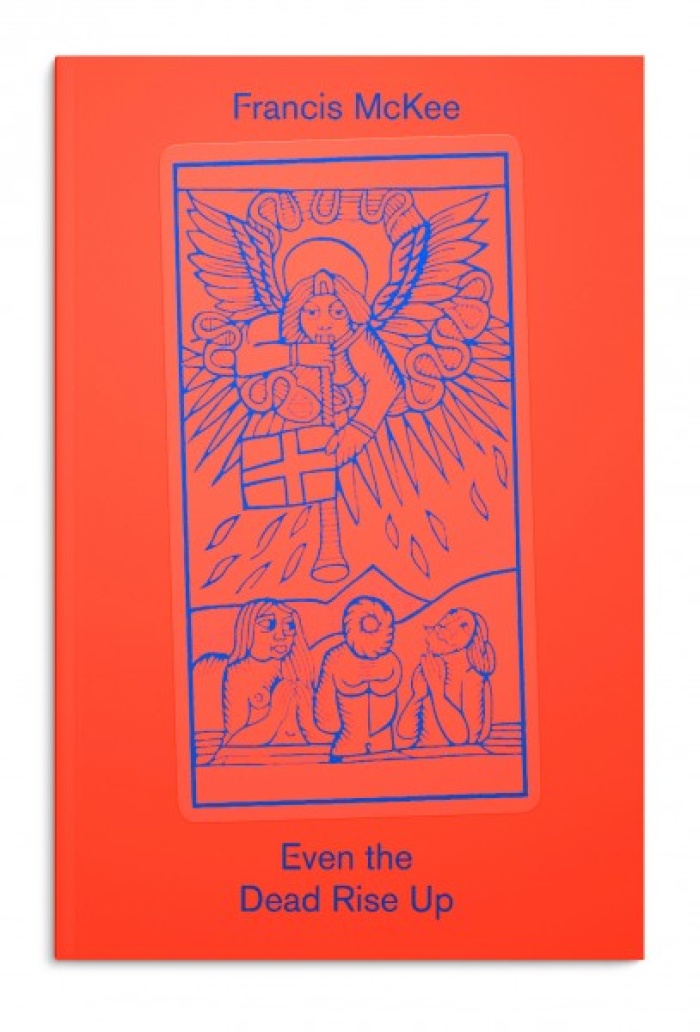

Okładka książki "Even the Dead Rise Up" autorstwa Francisa McKee. Dzięki uprzejmości Francisa McKee oraz Book Works.

Then you should have another publisher, right? Because the moment you pick up a certain publisher you know readership is going to be constrained mostly.

Yeah, but then I would have to write a proper novel. Which I wouldn’t mind doing and have also talked about a lot. I’m learning and I’m reading all these books called How to Write a Proper Novel. They’re pretty much called that. [Laughter]

Are you learning a lot from that?

I’m learning a lot, yeah. I know exactly how many chapters, how many words. I know my hero’s journey. You know, I’ve figured all that out.

And you’re missing all that in your previous book [Even the Dead Rise Up]? [Laughter]

Well the hero was me, which wasn’t very heroic. But I have a different hero for the next book. It’s a she, and I know where she’s going, I know what she’s doing, I know where she’s doing it, I know how many chapters she’s going to do it in, I know when she learns all those extra skills to fight so she can protect herself from the second phase of the book when she meets the enemy. You now, I have all that sorted. [Laughter]

With a little bit of luck we’ll see it in WHSmith soon?

Yeah, and it will become a movie. Like Rogue One or something. It would be ideal if it was Rogue One.

You are joking about it, but I spoke to an artist – I won’t say their name – that actually fantasised that their novel might end up like a Hollywood movie.

I’m not joking. But I’d have to write a really good one.

There is also one thing I wanted to speak about, because Joanna [Zielińska] and I have been researching artists’ novels but at the same time we have been stumbling upon a number of curators’ novels. Not intentionally, we just stumbled upon them. We are not going to research them …

As your revenge? [Laughter]

But without even looking very hard into them, we started to see a similar difference as in artists’ novels. Some curators write novels, like Tirdad Zolghadr, he wrote two and he’s writing his third one. Of course, the tone and the contents are art world related, but you could read it just like any other fiction. And then there are other curators who really write their novel, for example, as a catalogue for an exhibition they are curating. I wanted to ask you, from your perspective as a curator, how should we read your novel? How does it fit into your curatorial approach?

I’m not sure it does. I don’t think of it like that. I don’t think of it as fitting into a curatorial approach. I think of it as a book. But it has come out of those other pieces of writing for other artists, where they have asked me as curator to write for them and I’ve written something where I’ve tried to illuminate their work through a story. But there is no exhibition to go with this, so I haven’t written it in that sense. It’s a book without an exhibition, or a catalogue essay without an exhibition. And then I don’t want to have the exhibition. So no, I think I’ve tried to avoid that and tried not to think of the curatorial at all. Remember, I’ve never trained in art and I studied English Literature and became an historian of Medicine. So, the curatorial thing is not my lifeblood. It’s great, but I think of this separately. And, I’m Irish! Everyone in Ireland wants to write a novel. [Laughter] That’s the answer.

As they say, everybody has a novel inside.

Yeah, totally.

I also wanted to ask you about death, mediums and contact with ghosts. In Even the Dead Rise Up there is a ghost called Anna. Who is Anna?

I come from Northern Ireland. So, I come from an area where I grew up surrounded by bombs going off, and people being shot, and bodies being dumped outside the house and things like that. The place I described where she dies is a place I lived right next to. So, it’s a combination of a whole series of things I knew as a kid growing up. And I made this inventive character, which I then mock later because obviously she is a very good-looking young woman, which is kind of pathetic. [Laughter]

You know, a medium tells me this halfway through the book – that it’s a pathetic stereotype. Maybe that made it easier to tell that kind of story. And maybe that’s where the death thing comes from as well, that notion of being haunted. I don’t believe in ghosts and have gone to a lot of spiritualist things and am really fascinated by them, but I don’t believe a ghost comes back to tell you about your auntie’s rabbit that might die on Thursday, or that there is a real person-like out there. I think it is a bit more complicated than that. But I have taken a lot from that. I have taken a lot from the idea of ‘spirit’ and the political idea of spirit. And it’s the same as the protests. You see a lot of things in the protests now that are equally as horrific, and she stands in for all that, I think.

This is a kind of territory that overlaps with the [Alex Cecchetti’s] Tamam Shud performance that is coming right after – the dead people who speak after being dead. And there is also something that is common to both projects, which is the tarot. On the cover of your book you have "Judgment", the tarot card XX. Why did you choose this cover?

Well, it’s the second-to-the-last one. That’s when God is calling all the dead to judgment. So, everybody rises up. I was interested in everybody rising up. You know, post-Trump, post-Brexit, post-every protest everybody rising up, rather than going home to read about the ontology of photography. That, you know, that new Depeche Mode single, "Where’s the Revolution?" [Laughter] It’s kind of like that. I applied for this as a collective, actually.

Strona z "Even the Dead Rise Up" autorstwa Francisa Mc Kee. Dzięki uprzejmości Francisa McKee oraz Book Works.

Oh yeah?

Yeah, it was a series of collectives writing and I applied as "Me and the Dead" and they very generously gave it to me, which was lovely. And the dead are out there in various forms. And I am kind of interested in the dead rising up.

It’s a call to action, somehow.

It is, and the tarot is kind of fascinating like that.

Yeah, I wanted to ask you more about the tarot. Let me read a fragment. It’s very short, from page 136, where you describe this tarot card, The Hanged Man: "In the Marseilles deck he hangs upside down by his left leg while the right leg is bent at the knee making an L shape or an inverted 4. Although he’s dressed in a blue body stocking, his right leg is green, a similar colour to the two trees that flank him tightly. The trees have been thoroughly pruned and the branch stumps are bright red. With his wild blond hair almost brushing the ground, the hanged man’s head is a dropped sun and like a good sex pistol, his tongue sticks out defiantly."

The question is inevitable, why so many references to tarot?

Well, I really like the tarot. There there’s a guy called Enrique Enriquez in New York, who’s Venezuelan and has a hat. And he’s a very kind of hipsterish tarot reader, but he’s lovely because he’s quite therapeutic and he says, "Well, they’re just little bits of cardboard. You put them down, but people respond to them. You put down an image and people respond to the image depending on their mood and what’s happening and then you feed something back in response to their initial comment and they feed something back to you, and eventually you get some kind of analysis of what’s going on. And eventually people, what I’ve noticed is, people tell you what’s wrong, but they don’t know they’re telling you what’s wrong. They tell you the answer and they tell you their future, but their body tells you. Your body language is everything. I can see from how you’re sitting, how you put your hands, what you’re doing with your head, your hair – all of those things are all your body telling me stuff that you don’t know it’s telling me."

So, there’s a kind of cold reading in there. But if you actually have some empathy and listen and then construct a narrative from what people are saying and then reacting – which is weirdly a bit like art, suspiciously – if you go and look at a painting or you go and look at a video and you begin to think about that and respond to that, there is something you can do with that. The symbols are incredible. They’re very ambivalent and they’re very well-thought through to persuade you to think further. They’re open ended.

As I read somewhere: a machine for imagination, a machine to think through.

BIOS

Francis McKee is an Irish writer and curator working in Glasgow. From 2005–08 he was the director of Glasgow International, and since 2006 he has been the director at the Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow. Together with Ainslie Roddick, he is the editor of 2HB, a twice-yearly publication dedicated to creative and experimental writing in contemporary art. He is also a lecturer and research fellow at Glasgow School of Art. He curated the Scottish participation at the Venice Biennale with Kay Pallister in 2003. Francis McKee has written extensively on the work of artists linked to Glasgow such as Christine Borland, Ross Sinclair, Douglas Gordon, Simon Starling, Susan Philipsz and other international artists including Matthew Barney, Pipilotti Rist, Willie Doherty, Joao Penalva, and Abraham Cruzvillegas. He was one of the eight co-authors of the collaborative science-fiction novella PHILIP (2007), initiated by Heman Chong. He has recently published two books: How to Know What Is Really Happening (Mophradat/Sternberg, 2016) and Even the Dead Rise Up (Book Works, 2017).

David Maroto is a Spanish visual artist based in The Netherlands. He has an extensive, international artistic practice: 11th Havana Biennial; Artium, Museum of Contemporary Art (Vitoria); Extra City (Antwerp); S.M.A.K. (Ghent); EFA Project Space (New York); W139 (Amsterdam); among others. In 2011, he spent time at a residency in ISCP New York, where he met curator Joanna Zielińska and began a collaboration called The Book Lovers, a research project on the artist’s novel with the support of a number of international art organisations. He co-edited Artist Novels (Sternberg Press, Cricoteka, 2015), and published a gamebook called The Wheel of Fortune (2014), where games and the novel, two of his main interests, meet in one single form. Currently, he is working on the publication of The Artist’s Novel: The Novel as a Medium in the Visual Arts, a research project that includes the artist’s novel The Fantasy of the Novel. David holds a MFA from the Dutch Art Institute and is currently pursuing a PhD at Edinburgh College of Art.

*Cover photo: Book cover of Even the Dead Rise Up by Francis McKee. Graphic design: Erik Hartin, Moa Pårup (Sans Studio). (c) Sans Studio. Courtesy of Francis McKee, Book Works, and Sans Studio.