I was driving; the air was so polluted that I wondered if it was real or the fictional setting for an apocalyptic movie created by Ridley Scott. I stopped the car and, from over the bridge, took a glance at the landscape that resembled a collage: as if the buildings under construction and the tower cranes had separated the foreground layer from the city background and firmly stood on the cream-grey ground – phantasmagorical and surreal among the smog. I wrapped my shawl around me, took a picture and wrote down in my notebook: Tehran is a city that is constantly molting and multiplying its cancerous cells.

No Country for Architects

Right after ten years of work for architectural consulting firms – the main tasks of which were design and planning – I made a career change. After graduating from the Architecture program in Qazvin Azad University, I started working in large and renowned private companies which produced architectural and urban development plans. I remember that my first day at work coincided with Bashar al-Assad’s first-ever visit to Iran. My boss was reading a newspaper with a full-length portrait of Ahmadinejad and Assad on its front-page. Two soldiers behind them were giving salutes and the height difference between the two presidents was outstanding. As a new company member inclined to theory, planning, and studying urban architecture, I embarked on a national renovation project at a historic site and since then I have been employed in different counseling teams for sizeable projects. Today a glance at my CV reveals a decade’s activity, mostly on national and metropolitan scale projects, none of which were ever carried out, resulting in masses of Whiteprint plan copies, booklets, and documents piling up and moldering in the offices of some organization’s authorities: books upon books, dust upon dust.

The construction industry in Iran, as in many other places in the world, is hierarchical and complicated. A part of this system consists of design consulting companies, the other part includes contractors and tradesmen. The consultants and designers are generally not involved in the actual construction processes and their staffs are mainly composed of architects, engineers, and experts with higher education. The other category of companies and individuals – workers and contractors – are in charge of carrying out the construction work, their main workforces are made up of blue-collar workers. The consulting companies are idea-makers and problem-solvers covering a wide range of activities from feasibility studies, design, and proposals to monitoring construction sites, whereas the contractors are in charge of the physical, laborious act of construction. While the major body of consulting institutions are privately owned and populated by architects and urban planners prone to the criticism of the system, the main general contractors were gradually bought up by the country’s military forces up to today almost any colossal infrastructural or construction project is exclusively executed by a branch of the country’s Armed Forces. 1

Contrast of benefits, the multiplicity of stakeholders, and the influential organizations, as well as a heavy dependence on the state/military system/procedures forced consulting firms engaged with public projects to face a new crisis: some of them shut down their offices and others continued until they went bankrupt, or survived by way of layoffs or wages that are either low or in arrears. Because of this severe financial instability and abortive projects, many of my friends and colleagues resigned from counseling companies and sought other forms of employment in the field of architecture and urban planning. After ten years, I joined the throng.

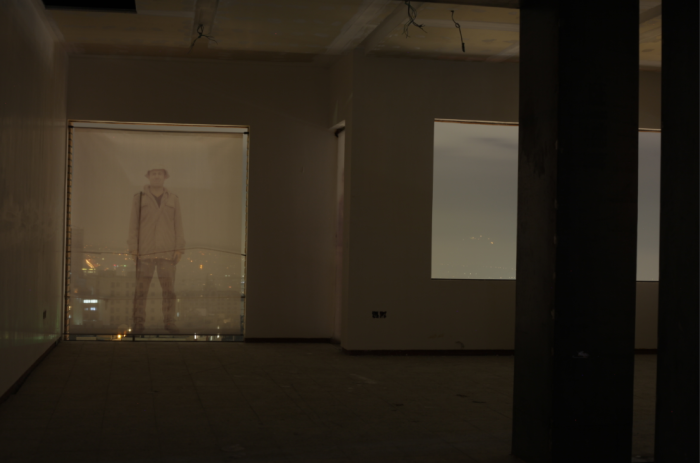

Machine for Living in. Instalacja, Mandana Mansouri, 2016. Dzięki uprzejmości Mostafy Qaheri

Machine for Living in. Instalacja, Mandana Mansouri, 2016. Dzięki uprzejmości Mostafy Qaheri

Machine for Living in. Instalacja, Mandana Mansouri, 2016. Dzięki uprzejmości Mostafy Qaheri

Tehran and the Uncountable2

Ten years after my graduation from the School of Architecture and right after my resignation from a famous yet almost-broke consulting company – I stepped into a construction site for the first time in my life: it was a five-story, ten-unit, residential building in Tehran. My dad and a few others had chipped in to start a jerry-builder business. It was an ordinary house; one of a million houses constructed by individuals. As building five to six-story houses is considered the secondary job of a number of people in Tehran. While the rise in salaries is not proportional to inflation and saving money or investment in banks (or other financial institutions) is equal to devaluation; gold and dollar prices are always unreliably changing, Iranian common sense, lived experience, and collective logic have concluded that the safest investment in the country is real estate: building and owning more houses. Accordingly, the majority of Iranians followed the double-employment solution: anyone with savings would invest in the construction business. Therefore, the houses outnumbered the city’s inhabitants. The accumulation of capital has given way to an accumulation of space: accumulation of empty dusty residential spaces, house upon house and dust upon dust.

The ultimate example of this story is Tehran: there is no consensus over the exact number of empty houses in Tehran. Five years ago, the head of the parliament’s financial commission had claimed that about two million and two hundred empty houses existed in Tehran at that time. Four years ago, the Minister of Roads and Urban Development of the time had maintained in an interview that there were around four hundred thousand empty houses in Tehran and considering those under construction, the total number would exceed one million empty units in Tehran. The number of empty houses in Tehran resembles the notion of a transcendental3 number which cannot be defined by any combination of a finite number of equations with rational integral coefficients.

Disappointed with the public space projects, I left the consulting and public projects firm and joined the community of junior, small-house builders. The scale had changed: from planning for multitudes to planning for individuals, from designing for a shapeless mass to designing for a human body, from negotiating with the government and the municipality to arguing with landowners, from the office to the site, from idea to administration, from intellectual labor to physical labor, from a bird’s-eye view to a person point of view, from above to within, from geometry, numbers, and computation to skin, flesh, and blood.

Uncountability of Flesh or Bare Life

In fact, if we are not hippies, we should be interested in the ownership of a dwelling. Although we all need a house/room of our own, for what reason should more houses be built in a city which does not need them? Who is building them? Which system of political economy is driving the city towards mass-production beyond its needs? Where does the will to accumulation come from? Who is building these houses? Do the ones involved in multiplying the residential cells of this city benefit equally? What does an analysis of the relationship between the owners of capital (land or money owners) and workers (body owners) reveal?

One spring morning in my first months of employment on the construction site, two blocks away from our site in another under-construction house, a worker had sleepwalked and fallen from the third floor. He was an illegal Afghan worker who had just turned twenty. In September 2017, the inspection director of the Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor, and Social Welfare stated that half of the incidents at work leading to death in Iran take place at construction sites.

A sizable amount of physical labor on construction sites is undertaken by Afghan immigrants. According to official statistics published in Iran, the community of two million Afghan workers holds about ten percent of Iran’s job market. The presence of Afghan workers has faced mass objections by Iranian workers and a number of demonstrations have been held against nationwide unemployment and to oppose employment of foreign labor. The Iranian government has perforce put limitations on foreign labor, such as prohibition against their employment in governmental and non-governmental public institutions as well as regulations demanding all governmental, non-governmental, and public companies and their contractors to only employ an Iranian workforce; any violation of the law by employers is followed by pecuniary or deterrent punishment. However, many employers in the private sector, mainly in the housing and construction industry, prefer to employ Afghan workers because they are cheaper, do not have insurance, and are more efficient and conscientious.

Machine for Living in. Instalacja, Mandana Mansouri, 2016. Dzięki uprzejmości Milada Houshmandzadeha

Machine for Living in. Instalacja, Mandana Mansouri, 2016. Dzięki uprzejmości Milada Houshmandzadeha

Machine for Living in. Instalacja, Mandana Mansouri, 2016. Dzięki uprzejmości Milada Houshmandzadeha

Machine for Living in. Instalacja, Mandana Mansouri, 2016. Dzięki uprzejmości Milada Houshmandzadeha

There is no certitude regarding the exact number of Afghan migrants or refugees with valid refugee documents in Iran: the Ministry of Refugees and Repatriations (MORR) of Afghanistan has estimated the number of refugees with or without documents in Iran at two million and 160 thousand people, out of which about three hundred thousand reside in Iran without any documents. According to the latest census (2016) of the Statistical Center of Iran, approximately one million and 584 thousand Afghan people live in Iran. This is only an official account of the number of Afghans in Iran, while it is estimated that the number of legal and illegal Afghans living in Iran would be between two to three million. According to official statistics, about forty-six percent of Afghan migrants in Iran are under twenty and about sixty-seven percent of them are under thirty.

Afghan migration to Iran started about fifty years ago with the Soviet-Afghan War and increased after the 9/11 with the American military invasion of Afghanistan. War, insecurity, and unemployment drove a huge number of Afghan people towards their western and southern neighbors – and the closest country speaking the same language was Iran.

Legal limitations for work and movement of Afghans in Iran have led to a situation that I would call “domestic exploitation”: the Tehrani citizens’ houses are constructed by (sometimes illegal) cheap migrant Afghan workforce. These workers often reside collectively in the construction sites/unfinished houses. Living in fear of deportation and confined to the construction sites, they are almost invisible/absent from the city to which they are contributing to its formation: the displaced who remains ignored.

Inaccessibility of the exact number of Afghan refugees in Iran recalls the mathematical concept of “uncountable sets”; the countability of a closed set depends on its one-to-one correspondence with the set of natural numbers. An analogy between the countability of Iranians and the uncountability of Afghans is a metaphorical restatement of their disconnection with the set of natural numbers, or in other words here, their state of citizenship – a state comparable to Agamben’s notion of “bare life”: a non-political and non-citizen life.

While there are no exact statistics regarding the number of displaced, non-citizen Afghans living in Iran, official Iranian news agencies have announced that more than two thousand Afghans have been martyred while protecting Iranian borders during the eight-year Iran-Iraq War. Meanwhile according to the New York Times, Deutsche Welle, and Human Rights Watch, since 2013, Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps have hired thousands of Afghan refugees lacking official residential documents and dispatched them to the war in Syria, resulting in two thousand Afghans killed and more than eight thousand injured.

Photography for Intimacy; Performance for Seeing

When I began working at the construction site, every worker, except for the supervisor, was Afghan. I started taking pictures of them and I am not sure what compelled me to do that – whether it was their closeness to danger and death, their “state of exception,” their invisibility to the city or my desire to get closer and get in touch with them, or maybe their exotic beauty. Nevertheless, the camera was a means of enabling and legitimizing my gaze. Although I took refuge behind the camera, I asked them to stare at me, I wanted a mutual gaze.

Later on, I was eager to display the photos but did not like the idea of putting them in a gallery; these images did not belong to the white cube, I was certain. Thinking of a visual strategy for displaying them, I came up with the idea of displacing photos and bodies: what if the workers come to the gallery instead of photos, and the photos were displayed at the construction site to dislocate the workers?

In order to present their bodies, I decided to take a worker to the gallery and ask him to stand in the middle of the hall, imitating Marina Abramović, and to gaze at the viewers/spectators. I suggested that there could be a stand by his side in the gallery to display his name, age, and daily wage. I wanted to entitle it as “Exercise Your Eyes So You Can See.” The gallery owner did not like the violence enforced on the worker. My second scenario was this: a worker is seated on a chair in one side in the gallery and there is a jackhammer on the other side of the space. Both objects are marked with a price and the year of production. The second scenario was also considered too brutal and therefore rejected. Finally, they agreed with this scenario: eighteen illegal Afghan workers come to the gallery to spend some time with Iranian viewers. The performance/platform was titled “A Machine for Living in.”4

Machine for Living in. Instalacja, Mandana Mansouri, 2016. Dzięki uprzejmości Milada Houshmandzadeha

Machine for Living in. Instalacja, Mandana Mansouri, 2016. Dzięki uprzejmości Milada Houshmandzadeha

Machine for Living in. Instalacja, Mandana Mansouri, 2016. Dzięki uprzejmości Milada Houshmandzadeha

On the day of the performance, the gallery was seriously cleaved in two and the fear of seeing – and being seen – was the Iranian viewers’ most significant reaction: one viewer told me after the performance that he felt uncomfortable, inhibited, and guilty for having seen them. Many talked about the racist aspect of the performance and why the created situation was so unequal.

The second part of the show involved a site-specific photo installation. Photos of the workers were printed to actual size on translucent material and installed in window frames of a half-built five-story house in the north of Tehran. Photos were distributed throughout all the floors. It was as though they were projected over the cityscape, the picture of bodies that had no place where they had been contributing to its construction. The experience of visiting this installment was only possible after the physical hardship of climbing up a half-built stairway so that one could shortly experience how these others made a living. 5

Epilogue: Dust to Dust

Now, I am not there; I left my country, not because Iran is being invaded by Russia or the United States, or not because of the civil war, or not because I am an environmental activist who is afraid of being arrested.

I'm not there, trying to write this fragmented personal narrative about the production of space and I experienced displacement in this writing: I can’t write about the production of residential spaces in the city that I grew up without thinking of the displaced bodies. I can’t stop thinking of Tehran’s houses apart from this constellation of invasions and wars:

- The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan,

- Iraq invasion of Iran,

- September 11 attacks,

- The United States' invasion of Afghanistan,

- Arab Spring,

- American/ Arab States/ British/ French/ Iranian/ Iraqi/ Israeli/ Lebanese/ Turkish (and all the companies and groups forces and arms) in the Syrian civil war.

Here I am, thinking of all the bodies that have been melted into the air, thinking of the hazy, blurred vision of a middle-eastern dusty cityscape, remembering the first day of working as an architect; a portrait of two presidents, facing the camera, saluting us.

BIO

Mandana Mansouri is an artist who works with still and moving images, language, performance, and site-specific installations. Her work is concerned with bare-life, power, production of space, displacement, and visibility. In her recent body of work, A Machine for Living in, Mansouri references the subject of labor exploitation and the visibility of Afghan refugees in Iran, both in the white cube and on the cityscape.

Mansouri was born in Kermanshah, Iran, in 1982, and currently works and lives in Vancouver. She holds a Bachelor's degree in Architecture from Azad University, Qazvin, a Master's in Urban Design from Azad University, Tehran, and is currently an MFA candidate at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Her work has been included in recent exhibitions at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver; Gallery 1515, Vancouver; and Azad Art Gallery, Tehran. Mansouri has collaborated with art collectives such as Photocopy, New Media Society, Architecture Urbanism Circle in Tehran. She used to work as an architect/urban designer for more than ten years, in this essay she articulates her personal narrative and experience of the production of residential spaces in Tehran.

*Cover photo: A Machine for Living in, Installation view, Mandana Mansouri, 2016. Coutesy of Milad Houshmandzadeh

[1] After the end of the war with Iraq, in 1989, Islamic Revolutionary Guard Cope, a branch of Iran's Armed Forces, was encouraged to start economic activities; to do that, IRGC established a headquarters for engineering and construction named Gharargahe Khatam al-Anbiya, abbreviated as Ghorb. The company became one of Iran’s major contractors in industrial and urban development projects.

[2] Learning from Badiou, here I am using some mathematical notions, mostly metaphorically. An uncountable [set] (or uncountably infinite set) is an infinite set that contains too many elements to be countable. The uncountability of a set is closely related to its cardinal number: a set is uncountable if its cardinal number is larger than that of the set of all-natural numbers.

[3] Math. Not capable of being produced by (a finite number of) the ordinary algebraical operations of addition, multiplication, involution, or their inverse operations; expressible in terms of the variable only in the form of an infinite series. (Adjective, OED Online, Oxford University Press).

[4] Addressing Le Corbusier's famous statement: “A house is a machine for living in.” He believed that modern life demands a new kind of plan, both in terms of housing and city-planning. Almost fifty years later, his ideas about housing have been criticized largely by post-modern thinkers, just after demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe public housing project as a symbol of the failure of modernist architecture. Racial segregation was an issue which has been discussed among critics.

[5] This installation was in dialogue with a piece named Census (2003) by Neda Razavipour and Shahab Fotouhi. The piece was an urban installation involved placing portraits of ordinary Iranian people in the windows of an unfinished high rise, with lights behind them that altered in brightness over time. It was an ironic comment on the logic of “census.” While the set of Iranian citizens is a countable set, their images were facing towards the city, in “The Machine for Living In,” portraits of displaced Afghans – members of an uncountable set – faced away from city, confined and gazed at the house of the others.