When Sy talks about his studio as part of the collective space of the Village des Arts, he does so with reference to the former Village des Arts and with a certain proprietary air. Perhaps this is to be expected. His personal history is intertwined with the history of the former and the current Village des Arts. The current Village des Arts, located near the Stade de l’Amitié, is the namesake of a site that has been mythologized in the history of Dakar’s art world.

Were you to meet El Hadji Sy in Dakar, you would likely find him in his studio at the Village des Arts located near the Stade de l’Amitié. This is where I met him in 1998 when I lived in Dakar for the first time to undertake ap year of research for my doctorate. I arrived at the Village des Arts on a sweltering August afternoon to interview artist Serigne Mbaye Camara, who recently had moved into a studio at the Village des Arts. Several artists had installed themselves and their materials in one of the Village’s fifty studios that year and it was a good opportunity to see the space. Our interview lasted for nearly two hours. Camara shared details about his art practice, his exhibitions, and his teaching while rainy season mosquitos feasted on my ankles. When we finished our interview, Camara accompanied me from his studio and we passed a group of artists chatting and drinking tea in the shade of a large tree. In keeping with Senegalese social practice, he introduced me to the group.

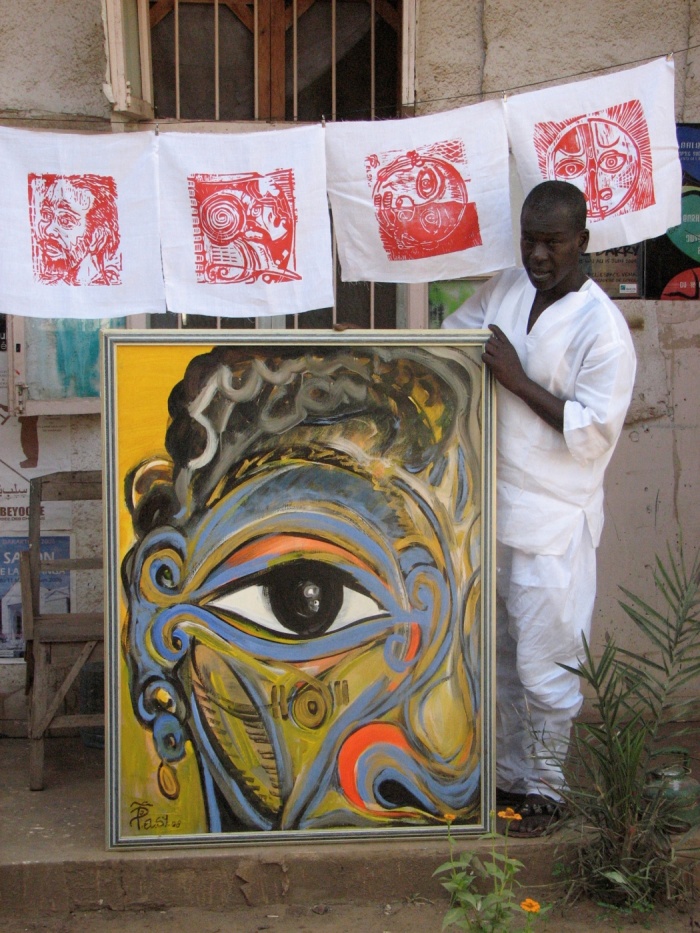

El Hadji Sy prezentuje prace malarskie na jucie podczas wizyty studyjnej autorki, Village des Arts, 1998. Zdjęcie dzięki uprzejmości autorki.

El Hadji Sy prezentuje prace malarskie na jucie podczas wizyty studyjnej autorki, Village des Arts, 1998. Zdjęcie dzięki uprzejmości autorki.

El Hadji Sy prezentuje prace malarskie na jucie podczas wizyty studyjnej autorki, Village des Arts, 1998. Zdjęcie dzięki uprzejmości autorki.

I explained that I was conducting interviews for my dissertation on artists and art institutions in Dakar. One of them, wearing a white t-shirt emblazoned with the word, Tenq, replied with a broad smile that he was an artist as well as a curator and an art historian. Camara introduced him as El Hadji Sy though he introduced himself as “El Sy”. We scheduled what would be the first of many formal interviews and informal conversations to take place in his studio between 1998 and 2014. His studio was jam-packed with works in progress, finished canvases leaning against the walls, containers of paint on the floor, a couch, a rocking chair, a fan, and books stacked on a small table. During our studio visits, Sy unpacked paintings from made-to-measure containers and set them up for me to photograph. Inevitably, we made our way outside to see the mixed media works displayed in the garden next to his studio. He moved his works from here to there and back again so I could take a closer look in the daylight.

Sy also shared his incredible archive of documents and photographs with me. From a metal trunk, he removed newspaper clippings with tattered edges, handwritten or typed letters on faded paper, and old black and white photographs. These were his “personal archives”, he told me. Some of them, elusive in institutional archives, would be critical to my future publications about Dakar. Along with documents and pictures, he also shared stories about the city he called home, his interventions in it, and his projects abroad. He took me to visit the murals he was commissioned to paint in the 1980s and 1990s. At one time, his murals enlivened the walls of Dakar’s private and public spaces—an Italian restaurant, the French Cultural Center, the Léopold Sédar Senghor International Airport, and the Foyer des Femmes Socialistes. The humid climate and the passage of time had faded their once bright images. In October 1998, he invited me to film the creation of another mural, this time undertaken by the artists’ collective, Huit Facettes, during their Téléfood performance.

Tworzenie muralu przez grupę Huit Facettes podczas ich performance Téléfood, 1998. Zdjęcie dzięki uprzejmości autorki.

Tworzenie muralu przez grupę Huit Facettes podczas ich performance Téléfood, 1998. Zdjęcie dzięki uprzejmości autorki.

Tworzenie muralu przez grupę Huit Facettes podczas ich performance Téléfood, 1998. Zdjęcie dzięki uprzejmości autorki.

Through the studio visits, I learned that Sy’s skills surpassed the expressionistic, colorful depictions for which he is well known. He was, in fact, a central force in mobilizing, articulating, or sustaining several collective artistic initiatives. These include the former and current Village des Arts, Tenq, the Laboratoire Agit’Art, Huit Facettes, and l’Association Nationale des Artistes Plasticiens du Sénégal (ANAPS).

His studio was jam-packed with works in progress, finished canvases leaning against the walls, containers of paint on the floor, a couch, a rocking chair, a fan, and books stacked on a small table.

Drawing upon my studio visits and interviews with Sy in a sixteen-year period from 1998 to 2014, this essay situates the artist in relation to his studio space and his city. In doing so, it traces the artist’s role in Dakar-based collective projects and maps the centrality of these initiatives to the history of Dakar’s art world, especially its localization, urbanization, and art world globalization. Because these projects were artist-led rather than institutionally driven, they underline Sy’s interventions, and the role of artists more generally, in creating infrastructure for the arts in Dakar. I view infrastructure not as defined by its physical or material form, but rather as “built networks that facilitate the flow of goods, people, or ideas and allow for their exchange over space.” [1] While this essay elaborates on Sy’s contribution to Dakar’s art scene by way of collective actions and interventions, it also centers the artist’s studio as a site from which to navigate the city’s art scene and its art world globalization. This is significant because it stresses that art world globalization happens from the position of artists’ studios in Dakar and because of the artists who live there, and not only from the impetus of individuals and institutions in metropolitan centers in Europe or North America.

The First Village des Arts: Interventions in Urban Space, Artistic Practice, and the Audience for Art

When Sy talks about his studio as part of the collective space of the Village des Arts, he does so with reference to the former Village des Arts and with a certain proprietary air. Perhaps this is to be expected. His personal history is intertwined with the history of the former and the current Village des Arts. The current Village des Arts, located near the Stade de l’Amitié, is the namesake of a site that has been mythologized in the history of Dakar’s art world.

The first Village des Arts was an artist’s community founded in 1977 when Sy’s search for studio space led him to squat in the unoccupied buildings of the former military barracks, Camp Lat-Dior, in downtown Dakar. [2] In the following months, a handful of recent graduates of L’Institut National des Arts du Sénégal including Aly Samb, Fodé Camara, Djibril André Diop, Serigne Ndiaye, Moussa Tine, Aly Traore, and Babacar Traore as well as Professor Paolo Paolucci joined him. In the course of seven years, nearly eighty artists created their studios in this abandoned military camp, which came to be known as the Village des Arts.

According to my conversations with Sy, one of the most striking aspects of the former Village is that artists founded the space and established a community among themselves. They even formed an organizational committee headed by the chef du village, Moussa Tine. Some of the artists set up residence at the Village, moving their families into their studios. Even without electricity or running water this site was remembered as a productive space for making art and building artistic community. Its location in downtown Dakar next to L’Institut National des Arts du Sénégal, the sprawling Sandaga Market, and the public transportation center provided easy access to and from the city center.

Because the artists working at the Village des Arts came together by their own initiative to find workspace and because they did so without the government’s authorization, the Village was connoted almost immediately as an “alternative” and “unofficial” site. These connotations were further reinforced vis-à-vis the Cité des Artistes, a group of studios created with government support in the Colobane neighborhood in 1979. While the Cité des Artistes included thirteen painters, all of whom were associated with the immediate post-independence era and government sponsored exhibitions, the Village des Arts was associated with the second generation of artists in Dakar. [3] In relation to the history of art in Dakar, the second generation of artists challenged precedent artistic practices and art’s association with the state sponsored projects of former President Léopold Sédar Senghor. They disrupted narratives about art, national identity, and Négritude.

From a historical viewpoint, the first Village des Arts was a precursor to the many contemporary artist-led platforms for animation artistique and infrastructures for collaboration that have sprung up in neighborhoods across Dakar.

The Village des Arts contributed to centralizing the art scene in the city and away from the synecdoche of Senghor’s shadow. These shifts were, in turn, crucial to creating Dakar’s current art scene. The Village’s location on Avenue Peytavin, one of the city’s major downtown crossroads, represented a literal, physical move into urban space for artists and their projects. Artists working and living at the Village contributed to creating the context for what I identify as the “the urban turn” in Dakar’s art scene. [4] One of the main ways artists redirected the art scene to urban space was by collaborative practices such as exhibitions and workshops. Rather than participating in government-sponsored exhibitions, artists at the Village des Arts devised alternative events and activities to display and discuss art.

The Village des Arts not only offered infrastructure for artists and the arts in the city; it also brought the art scene closer to the city’s population. In doing so, it sparked the imagination about what the arts could be, for whom, and how art and artists might participate in the city’s changing landscape. The Village provided a space to host exhibitions, film screenings, and performances as well as debates about art and culture. Friends and family members as well as those interested in the arts visited this site and participated in its events. From a historical viewpoint, the first Village des Arts was a precursor to the many contemporary artist-led platforms for animation artistique and infrastructures for collaboration that have sprung up in neighborhoods across Dakar.

The artists who participated in the first Village des Arts recall that the site offered much more than workspace. Given the diversity of its practitioners, the Village offered the ideal environment for cross-disciplinary interaction and experimentation. Several artists have spoken nostalgically about the days when they worked with studio doors open, exchanging materials, advice, and criticism with their peers. The ambience of individuals working in a variety of media also fueled experimentation with new materials and techniques. Sy observed during an interview in 1999 that, “the Village’s interdisciplinarity took artists’ practices in new directions.” Through experimentation and collaboration artists developed new modes of working that were based on dialogue with each other.

With every return to Dakar, I found Sy at the Village des Arts, working, chatting with visitors, or giving directions to someone about something. The aroma of incense and espresso wafting from the open door of atelier B1 signaled that the artist was in his studio or in the vicinity

Two well-known artist-led collectives - Tenq and the Laboratoire Agit’ Art - benefited from the Village’s climate of interdisciplinary experimentation. Sy founded Tenq in 1980 at the Village des Arts as an artist-led series of events including exhibitions, concerts, plays, lectures, and film screenings. Visual artists, writers, and filmmakers as well as professors and students at the art school located next door were participants. During the Village’s lifespan, a Tenq program was organized nearly every year. The Wolof term, Tenq, denotes a connecting structure or joint, and the project intended to connect and facilitate interaction among artists as well as between artists and the city’s emerging audiences for art. [5]

During the Tenq programs, Sy transformed his studio into the Tenq gallery where several artists displayed their work. Like the Village des Arts, the Tenq program represented an alternative space for artists to exhibit their works and engage in a critical, interactive forum. Several artists emphasized two motivations for their participation in Tenq’s exhibitions. First, they sought to establish an alternative exhibition venue that was not associated with the state. Secondly, they intended to create a space for the arts that was accessible to the city’s interested audience. In addition to providing a forum for dialogue, the Tenq program contributed to localizing and urbanizing the city’s art scene because its intention was to enlarge the local audience’s appreciation for and interest in artistic work. Until then, exhibitions in the 1960s and 1970s were sponsored by the state and were destined primarily for an international audience. According to Sy, one of Tenq’s objectives was to “confront art and artists’ dislocation from the Dakarois audience.”

The Laboratoire Agit’ Art is another collaboration that drew from the human and creative infrastructure at the Village des Arts. With Sy as the Laboratoire Agit’ Art’s longtime member and Artistic Director, the group often met at the Village. Because participation in the Laboratoire is, as Sy explained, “by cooptation or invitation,” several of the Village’s artists were participants. Sy recalled that individuals with studios at the Village or who frequented the Village participated in the Laboratoire’s activities. They included painters Fodé Camara, Serigne Ndiaye, and Kalidou Sy; sculptors Djibril André Diop and Babacar Traore; photographers Bouna Médoune Seye and Djibril Sy; architect Pierre Goudiaby; poet Thierno Seydou Sall; and philosopher As Mbengue. The Laboratoire intervened in Dakar’s art scene just as it linked the city to a map of global art world activities with its participation in the exhibitions, “Laboratorium,” in Anvers in 1999 and “Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa” in London in 1995.

The End of the First Village des Arts and the Fight for a New Village des Arts

According to Sy, in the early 1980s, the Senegalese government notified artists at the Village des Arts that the site was slated to become bureaucratic offices for the Ministry of Technical Administration, Water Supply, and Tourism. Although the artists had received several notifications and visits from government officials, they refused to leave their studios. They even contacted former President Senghor, who drafted a letter to his successor, President Diouf, on behalf of the artists. [6] Despite their efforts, the government dispatched several hundred soldiers to evict the artists on September 23, 1983. Arriving in military vehicles, the government troops forcibly removed the artists from the Village des Arts. In the process, countless artworks were destroyed. [7]

Sy suggested that artists were ousted from their studio space because President Diouf wanted to send a clear message regarding his position on state support for the arts: he had no intention of continuing the patronage of Senghor’s government. Diouf’s government, on the other hand, maintained that the artists were using government property illegally. In any case, closing the Village des Arts marked a decisive moment for the art scene. Not only did it signal a definitive shift in the relationship between artists and the state. It also initiated a decade-long struggle to reclaim the Village des Arts.

Following their expulsion from the Village, artists organized a professional organization, l’Association Nationale des Artistes Plasticiens du Sénégal (ANAPS). With Sy as the President of ANAPS from 1985 to 1987, one of its primary goals was to persuade governmental authorities to return the Village des Arts to the artists who created it. Efforts were sustained but fruitless for more than a decade until Sy met with former Minister of Culture Abdoulaye Elimane Kane about a potential site Sy identified to host the Tenq workshop in conjunction with the Dak’Art Biennale in 1996. Whereas Tenq incorporated Dakar-based participants in the past, it was re-envisioned in the 1990s as an international artists’ workshop that capitalized on the international scope of the Dak’Art Biennale as well as the art world’s increasingly global scope. In 1994, the Tenq workshop was held in Saint-Louis, Senegal in conjunction with the events of Africa ’95 and in 1996, it was organized collaterally with the Dak’Art Biennale.

The Wolof term, Tenq, denotes a connecting structure or joint, and the project intended to connect and facilitate interaction among artists as well as between artists and the city’s emerging audiences for art.

To host Tenq during the 1996 Biennale, Sy identified several hectares of land situated near the growing neighborhoods of Yoff, Sud Foire, and Nord Foire. The land had been the Campement Chinois (Chinese camp) that offered temporary housing for the Chinese workers who built the Stade de l’Amitié in the 1980s. Their labor was part of a diplomatic and economic agreement between China and Senegal whereby the former built a sports stadium in exchange for trade privileges with the latter. When the Chinese laborers completed the stadium, the camp remained empty. Its single-story barracks were easily transformed into studios.

Convinced of the potential merits of the Tenq workshop, Minister Kane gave Sy the keys to the Campement Chinois. In addition to making art, artists in the Tenq workshop cleared overgrown foliage, rid the grounds of snakes, and made the space their own. When the workshop finished, Sy stayed at the camp as a squatter, refusing to leave on the premise that the space was promised to artists as the new Village des Arts. Eventually, a series of negotiations led to the site’s inauguration in 1998 by First Minister Habib Thiam. The artists had finally won their battle for a new Village des Arts [8]. Along with Sy, several artists who were active at the former Village, including Djibril André Diop, Ibrahima Kébé, and Moussa Tine settled into studios in the new Village.

The New Village des Arts

The new Village des Arts mirrors the former Village in its provision of workspace for artists. It also retains some of the collaborative character of the former Village. It is a site for hosting various workshops, exhibitions, and other events. For instance, in conjunction with the Dak’Art Biennale Off program in 2010, Sy and I co-organized “The Printed Image,” a printmaking workshop with American artist Craig Subler. A handful of artists with studios at the Village participated. At the same time, however, appreciable differences distinguish the current Village des Arts from its precursor. Perhaps most readily apparent, the new Village is not inscribed as an unofficial or alternative space as was the former Village. The plaque at the Village’s entrance makes clear that it was designated for artists by the government. The backstory of the former Village des Arts is likely unknown to most visitors.

Furthermore, the former Village’s location next to the art school contributed to its identity as a space for formally trained artists. In fact, the majority of visual artists at the Village in the late 1970s and early 1980s attended or graduated from L’Institut National des Arts du Sénégal. In contrast, the current Village encompasses a mix of formally trained and self-taught artists. Any artist seeking a studio at the Village may apply at the Ministry of Culture. The only qualifications for requesting studio space are that artists are actively making and exhibiting art. The result is that the current Village is an inclusive and pluralistic space. Touring the Village’s studios impresses the wide range of practitioners and propositions. In a nod to Dakar’s position in art world globalization, Sy also pointed out that two studios are reserved for international artists seeking space to work.

An excerpt from the 2010 edition of the popular travel guide, Lonely Planet, conveys that the new Village is a destination for visitors: “Without a stop at Dakar’s famous Village des Arts, an arts tour around Dakar is simply not complete.

The most significant distinction between the former and current Villages is the amount and type of studio traffic. While the current Village, situated near the Stade de l’Amitié, does not benefit from the downtown location of the former Village, it is a space open to the Dakar public and it attracts a population characteristic of the city’s intensified urbanization and art world globalization. Its traffic thus incorporates many variations of art enthusiasts. Visitors to the Village represent the diverse populations that make up or move through present day Dakar and its art scene.

An excerpt from the 2010 edition of the popular travel guide, Lonely Planet, conveys that the new Village is a destination for visitors: “Without a stop at Dakar’s famous Village des Arts, an arts tour around Dakar is simply not complete. More than 30 photographers, painters and sculptors create, shape, and display their works in this large garden space. An on-site gallery shows a selection of their work and the nearby restaurant is the place to have a drink and chat with the artists.” [9] In addition to suggesting the spectrum of artists and artistic forms at the Village des Arts, this excerpt also foregrounds a critical aspect of Dakar’s art scene. It is a highly relational space based on social interactions around art.

With every return to Dakar, I found Sy at the Village des Arts, working, chatting with visitors, or giving directions to someone about something. The aroma of incense and espresso wafting from the open door of atelier B1 signaled that the artist was in his studio or in the vicinity. To encounter Sy at the Village typically involved trying to catch him as he moved between his studio proper, the adjoining closet, and a table in the garden where he paints while listening to BBC news from a small radio.

On any given day, visitors come and go from the Village. Sy and the visitors greet each other. He knows some of them, others he meets for the first time. Visitors arrive by the carload on weekends, parking their vehicles in the sandy brush at the Village’s entrance. They include a delegation from Senegal’s Ministry of Culture, a Japanese diplomat, a group of French art enthusiasts living in Dakar, a well-known Senegalese collector, members of the Dakar Women’s Group looking for participants for their annual charity auction, and an American art historian scheduled for a studio visit.

The visitors interrupt Sy’s painting; he stops to show them his work, leading them into his studio and back outside again. They exchange questions and answers while smiling and nodding. Some minutes later, Sy escorts them to Ibrahima Kébé’s studio where they scan the floor to ceiling display of painted canvases rendered in bright, unblended colors. Kébé’s lively scenes of daily life, children playing, and women preparing food are favorites among Dakar’s many expatriate art enthusiasts. After looking at the artist’s price list, the visitors thank him and propose to return another time. They make their way through the Village des Arts, stopping at studios with doors ajar. Looking at the panoply of art forms, from painting and drawing to photography and sculpture, the visitors strike up conversations with artists Mamadou Touré dit Behan, Serigne Mbaye Camara, Djibril André Diop, Mouhamadou Dia, and Moussa Tine among others.

Selling art makes use of practices that characterize Dakar’s commercial and relational culture more generally.

While the Village’s purpose is to offer workspace for artists, it has become equally known as a social and commercial space. The conflation of purposes is largely related to Dakar’s urbanization, especially its contemporary status as a tourist destination and hub for international business, diplomacy, and the non-profit sector. At the same time, Dakar is a destination for art world travelers. In addition to the occasional buyers and dedicated collectors who live in Dakar, a steady flow of art world travelers--curators, gallerists, and collectors--touch down in Dakar, make studio visits, and then depart. Their presence in Dakar’s art scene corresponds with emerging art world globalization in the 1990s when gallerists and curators based in Europe or North America looked to Dakar for inventory for exhibitions. They came to Dakar to meet artists, make studio visits, and acquire work. The several museum and foundation collections that took shape between 2000 and 2015 are indices of art world globalization. Examples include the Fondation Blachère and the World Bank Art Program along with private collectors and museums. Like many artists in Dakar, Sy sells his works to diverse categories of buyers including of Dakar-based collectors, expatriate collectors and occasional art buyers, art world figures, and other travelers.

Despite the presumed differences among these populations and the geographical separation suggested by their points of origin, their transactions have enormous potential to bear on each other. This draws our attention to the back and forth processes of art world globalization as well as the role of artists in these processes. In Sy’s case, for instance, his exhibition at the Weltkulturen Museum was based on the artist’s contribution to the art scene in Dakar as well as his role in assembling a collection of Senegalese art in Frankfurt. In turn, the exhibition’s international profile will reinforce Sy’s professional capital and credentials in Dakar, likely stimulating demand for his work in his home city’s art scene.

As the years passed, it was impossible not to notice the contents of Sy’s studio spilling into the adjacent garden space. Colorful canvases hung from rafters while mixed-media works stood tall on wooden bases among the foliage. A bright blue tarp covered an improvised closet adjoining Sy’s studio. “What do you have behind the tarp?” I asked. “Canvases from anterior moments,” he told me. When I asked why he was storing dozens of paint-on-canvas works, he responded by explaining that he chose “not to sell them because in the future they will be worth something different.” [10] Sy was right. The value of art and the dynamics of market demand change over time.

Our exchange points out another critical aspect of Dakar’s art scene. Like artists at the Village des Arts and in Dakar more broadly, Sy exhibits and sells artwork in a range of sites. Artists sell their work in exhibition venues and galleries as well as spaces not designated exclusively for the sale of art. Very often, artists in Dakar sell their works from their studios. In fact, many more transactions around art happen in artists’ studios than in galleries. This means that artists are both the makers and sellers of images. In my experience, they are also among the city’s savviest business people. Selling art makes use of practices that characterize Dakar’s commercial and relational culture more generally. For instance, visual perspicacity and social acumen are essential to commercial success. During face-to-face interactions, artists and buyers negotiate sales. They speculate on the intentions, limits, and possibilities of one another.

Just as visual proficiency is important, so too is social proficiency. Success in the art market or any of Dakar’s markets involves knowing how to create and maintain relationships while navigating the possibilities they offer. Given the importance of social interactions to commercial transactions, artists work hard at cultivating relationships and keeping them open. The work of sociality happens in several contexts including studio visits, exhibitions, and social gatherings. Conversations struck up casually between artists and prospective buyers at social gatherings lead to studio visits and, quite often, to the sale of art. As I have written elsewhere, the accessibility of artists to buyers is fundamental to the city’s art market because it allows for sales to take place without a middleman. Even when sales are not made at an exhibition, this is often the first point of contact for a potential buyer who then visits an artist’s studio and buys directly. The fact that prospective buyers can go directly to artists’ studios to purchase a work is the main reason galleries in Dakar rarely prosper.

Sy prezentujący swój obraz do zdjęcia autorki, czerwiec 2009. Dzięki uprzejmości autorki.

Tablica pamiątkowa dotycząca inauguracji Village des Arts, maj 2010. Dzięki uprzejmości autorki.

Widok na bramę Village des Arts, maj 2010. Dzięki uprzejmości autorki.

Widok wnętrza studia artysty, wrzesień 2013. Dzięki uprzejmości autorki.

Widok wnętrza studia El Sy, maj 2013. Dzięki uprzejmości autorki.

Artysci podczas warsztatów „Obraz drukowany” w Village des Arts w ramach programu Off Dak'Art Biennale 2010. Działanie zorganizowane przez amerykańskiego artystę Craiga Sublera, El Hadji Sy i autorkę. Dzięki uprzejmości autorki.

Nocny widok na z ogrodu studia EL Sy, Atelier B1, Village des Arts, Czerwiec 2009. Dzięki uprzejmości autorki.

Widok na wnętrze studia El Hadji Sy. Zdjęcie z wizyty studyjnej autorki, 2010. Dzięki uprzejmości autorki.

Olej na płótnie El Hadji Sy, „Handlarz obrazów” (2002). Kolekcja prywatna. Fotografia i prawa: James Spearman.

Sy’s oil on canvas The Image Seller (2002) offers a springboard for reflection on the dynamics of art world transactions in studio spaces. I saw Sy working on this canvas in his studio in the summer of 2002. Given the resemblance between the artist and the painted life-size silhouette, I asked him if he was painting a portrait. He looked at me and explained that the silhouette depicts an ambulant vendor peddling photographs of popular subjects such as soccer heroes and religious leaders on Dakar’s streets. At the same time, The Image Seller makes a striking reference to the artist’s role in selling images. It alludes to the importance of mobility and the practices of sociality in direct transactions around art. Those who sell images do so by navigating skillfully in their city and beyond. Certainly, this can be said of the artist.

BIO

Joanna Grabski is a Professor and Chair of Art History and Visual Culture at Denison University. Her book, Art World City: The Creative Economy of Artists and Urban Life in Dakar, is the product of seventeen years of research with artists, collectors, and art world mediators in Dakar, Senegal (forthcoming from Indiana University Press in 2016). She is also co-editor of African Art, Interviews, Narratives: Bodies of Knowledge at Work (Indiana University Press, 2013) and guest editor for a special issue of Africa Today dedicated to “Visual Experience in Urban Africa” (2007). Her essays on artists, urban creative expression, and visual life in Dakar have been featured in several edited collections and journals, including Art Journal, African Arts, Fashion Theory, Nka, Présence Francophone, and Social Dynamics. In 2012, she wrote, directed, and produced the feature length documentary film, Market Imaginary (distributed by Indiana University Press), focused on Dakar’s sprawling Colobane market, famous as a crossroads for secondhand clothing, shoes, and electronics.

*Cover photo: Entrance to the Village des Arts viewed from the autoroute and plaque commemorating the inauguration of the Village des Arts, May 2010.

1. Brian Larkin “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (2013): 328-329.

2. Friedrich Axt, and El Hadji Moussa Babacar Sy, Bildende Kunst Der Gegenwart in Senegal (Frankfurt am Main: Museum für Völkerkunde, 1989), 107.

3. Axt and Sy, Bildende Kunst, 107-108.

4. Joanna Grabski, Art World City: The Creative Economy of Artists and Urban Life in Dakar (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, forthcoming 2016).

5. El Hadji Sy, interview with author, May 24, 1999.

6. Axt and Sy, Bildende Kunst, 108.

7. El Hadji Sy, interview with author, October 21, 1998.

8. El Hadji Sy, interview with author, March 1999.

9. Katharina Kane, Lonely Planet The Gambia and Senegal, (Fourth Edition Oakland, CA: Lonely Planet, 2009), 161.

10. El Hadji Sy, conversation with author, May 18, 2011.