- Perhaps you see many difficulties in the way of your being so much on the beauty side that you can make it your good?

- I have no difficulty that can’t be easily overcome. My inclinations lead me strongly this way: for I’m ready to concede that there is no real good except the enjoyment of beauty.

(Shaftesbury, Moralists, a Philosophical Rhapsody)

Lantian D, Portret Rogera Scrutona,120 x 60cm, 2014

Lantian D i Roger Scruton, Royal Society Portrait Painters, Mall Galleries, Londyn 4.05.2016

Prologue

In 2016, at the annual exhibition organised by Royal Society of Portrait Painters in Mall Galleries in London, a female artist Lantian D won the main prize for Roger Scruton portrait [1].

The painting shows the philosopher, sitting on the bed/couch, portrayed by the artist in a very uncomfortable situation for a seemingly caring for appearances Englishman of culture and a conservatist. We do not know whether he is about to go to sleep or he has just got up: his clothing is incomplete – feet wearing only socks in disarray along with inattentively held up leg of his trousers. Correctly painted white draped textile/bedsheet cross-refers, in an imposing way, two pieces of art: The Unmade Bed (1827) by Eugène Delacroix and My Bed (1998) by Tracey Emin. Scruton frequently contrasted these two claiming that jumbled bedsheet of the French painter sparks reflection about human condition while Emin’s installation possesses no real value whatsoever. The background shows a mysterious horse/donkey head, winding river of Cam with a twisted tree leaning over it and the University of Cambridge in the distance.

Intrigued by the painting, I asked Lantian for a comment. In 2014, at one of the meetings with Scruton, she proposed to paint him. He keenly agreed and posed for the painting in his studio on Piccadilly Street.

As it turned out, sofa that he was to sit on, was covered with white sheet because its flowery padding seemed too distracting. The tree copied from a famous Chinese silk from 12th century’s Ting Qin Tu (Listening to the Qin) indicates author’s country of origin. The donkey, borrowed from the painting Pierrot (1719) by Watteau symbolises the figure of Don Kichote. The donkey wanting to be a horse similarly to the nobleman from La Mancha aspiring to be a knight errant, undoing all the evil in the world while being exposed to many dangers and ridiculed a number of times. It is easy to imagine Lantian who, with an innocent smile, says: “well, I foresaw that two years later Roger Scruton will be dubbed a knight by the Queen” (2016 Queen’s Birthday Honours List). The philosopher was not thrilled by the final version of the portrait enriched by the author with “attributes” that were to characterise him; in particular, he was not keen on seeing the donkey there – he preferred it to be a horse.

It is time the explain the reasons as to why I dedicated so many introductory paragraphs to the portrait and its author. In one of his last interviews on the condition of modern art, Scruton exemplifies Lantian’s painting as the kind of art that has a potential, particularly the realistic portrayal of people in London underground[2].

Lantian, Miłość

It would seem that having specific piece of art, esteemed by the philosopher himself, in front of one’s eyes would make it easier to understand Scruton’s perception of beauty and enthusiasm with which he stood by this term. Nothing can be further from the truth.

Starting point

The nature of beauty and the very essence of art are the utmost fundamental and controversial questions of western aesthetics. The issue was raised by Greek philosophers, scholars, Renaissance humanists. Beauty was in the center of aesthetic thought’s attention since 18th century, represented by such philosophers as Shaftesbury, Hume, Burke, Kant, Schiller, Hegel, Schopenhauer and Santayana.

Despite the fact that 20th century avant-garde divide brought “the escape” from beauty, the interest in this term did not waned. Roger Scruton referred to issues of beauty and art in numerous publications and speeches, two of which deserve particular attention: a documentary entitled Why Beauty Matters (2009) and a tiny book Beauty: A Very Short Introduction (2011).

The philosopher claims that beauty is a universal human need that gives life meaning. It brings consolation in times of sadness and happiness of affirmation. It is a value equally important to truth and good however it does not have a similarly unequivocal status. Only a few of us have doubts that we should strive towards the good and believe the real. Beauty is somewhat different. Along with “removing a spell from the world”, when beauty lost its divine attribute, a common belief that it was the emanation of God was no more, the “aesthetical” way of life contrasted with the moral life.

Scruton aims to convince us that beauty, just like good and truth, have always been one of the ultimate values[3]. By the ultimate value he understands something we pursue for the sake of the value itself with no additional justification required[4]. However, the problem here is that the English philosopher declared attempting to prove this thesis with no reference to theological argumentation. Let us see whether he was successful.

According to definition that says “beautiful is that from which we can derive pleasure by contemplating it as a single subject, for itself, in a form it manifests itself” [translated by Jakub Bujno][5], Scruton introduces a few logical arguments to test the theory of beauty: 1. beauty always brings pleasure; 2. one thing can be more beautiful than the other; 3. beauty always contributes to greater mindfulness towards the object characterised by it; 4. beauty is a subject of judgement and this judgement is the judgement of taste; 5. the judgement of taste concerns a beautiful object, not a subjective state of mind – when describing an object as beautiful, I describe the object, not myself; 6. judgements of beauty are direct judgements[6].

Paradoxes of pleasure

Is it possible to say that beauty always brings us pleasure? To confirm it is to agree with obvious consequences to the definition of beauty, since we could not regard in this way things that are terrifying and intimidating, even if they were of high aesthetical value. The implication of the opposite cannot be applied here as well. It is not true that what always brings us pleasure is beautiful. Pleasure derived from communing with an object/a piece of art with no value Scruton would call “false” while, contrastingly, ethical critic Berys Gaut would say that it is an unmerited response[7].

Scruton rarely uses the term “sublime” that describes qualities which, unlike beauty, do not bring gratification – in a sense of experiencing pleasure – that are caused by proportion, harmony and subtlety. Perhaps sublimity seemed too broad a term for him, able to encapsulate pieces of art presenting ordinary ugliness.

Paradoxically, Scruton believes that judgment over the subject of beauty, made even by the most sensitive and highly educated professional, will never be ranked as a scientific statement: “The judgement of taste is an authentical judgement with a rational justification. Yet, such justification must never be identical to a deductive argument” [translated by Jakub Bujno][8]. If the opposite were true, in case of doubt we would appeal to beauty judges and tribunals trusting in their fair judgment as to what should bring us aesthetical pleasure. The philosopher draws attention to the necessity of consensus both in the matter of morality and beauty. Criticising one’s taste is offensive because feeling beauty is an expression of human identity. One cannot simply persuade somebody into liking something just because rational arguments were used.

Independent interest

The subject of the esthetical judgement is beauty and its distinctive characteristics is independence – according to the theory. A flagship example of aesthetical independence supporters, that was used even by Shaftesbury and Kant, involves interest in the beauty of nature. Scruton gives an example of lush, green grass and a cow which “is standing in the field and is looking around in wonder, we can say that it is interested in what is happening (especially in potential dangers for its safety) but it does not find any interest in the view straggling in front of its eyes” [translated by Jakub Bujno][9].

Scruton’s enthusiasm towards spiritual potential of man is expressed by the example: “When you stop to look at wild flowers or a composition of birds’ feathers, you experience an intensified feeling of belonging. […] It appears as though the natural world, captured in consciousness, justified itself and, simultaneously, for itself. Such experience is of metaphysical kind” [translated by Jakub Bujno][10]. The philosopher believes that aesthetical look into the beauty of nature is congruent for all people. He is deeply convinced that even uneducated and sadistically pragmatic people experience natural beauty, though they are not able to describe this experience using terms, just as they could not describe their love if they were in love.

An unbiased attitude towards art is supposed to be similar “we are interested in a piece of art for itself, due to its »internal value«, a goal in itself” [translated by Jakub Bujno][11].

The philosopher thinks that even when we are not able to fully comprehend above terms we know that we like a piece of art/an item and we are interested in it for purely aesthetical reasons (Kant’s “purposeful purposelessness” of beauty problem).

I do not believe that this comparison between self-interested attitude of a feeding animal and a thinking creature contemplating the view works – and it is not always – in the scenery of nature. However, in spaces where we expect beauty things are completely different. An innocent eye does not exist in the same way total impartiality does not occur.

I am sceptical towards the optimism concerning the universality of experiencing beauty. I am afraid that not all people are able to love. Love and beauty require the grace of transcendence.

Minimal beauty

When Scruton enumerates evaluative judgements’ graduality among other obvious truths about beauty, simultaneously he defends aesthetical minimalism. He claims that a diligently set table, a thoroughly tidied room, a professionally designed website, a good pair of shoes, and, particularly, “minimal beauty of unpretentious street” affect the viewer in the same way as the great beauty of masterpieces and historic architecture achievements – not only do they bring pleasure for the eye, but also carry important meanings that possess higher value in everyday life than inaccessible pieces of art.

Provided there are things beautiful and more beautiful, one should strive towards the latter. An aesthetical common sense is required here, the one which forces to look around and, if possible, alter the surroundings in a way that our feeling of harmony is not excessively offended.

Art

Scruton is disappointed with contemporary art which – as he says – anaesthetised tragedy, sadness and grief until they became trivially superficial where everything is fun and pleasure, a contradicting the reality of loss and death. He is a strict critic of modern art, therefore when he writes that “the art accepted the torch of beauty, ran with it and dropped it in the latrines of Paris” [translated by Jakub Bujno] [12], we can be certain that he refers to Marcel Duchamp. It is notable that Scruton appreciated humorous “gesture” of the artist exhibiting urinal as The Fountain (1917), yet he could not accept an entire crowd of epigons that came afterwards. I must skip references to a wide and very interesting artistic and aesthetic issue inspired by actions of this French artist. I will confine myself to two questions that the philosopher asks: 1. how shall we be elevated, improved, led to find our place in the world and in a community with others by the art devoid of the power of beauty – a urinal and boxes, not to mention other debilitating manifestations?; 2. why is it a rule in contemporary’s world critique to defend every, even most nonsensical, and sometimes an offending artifact?

The first question is a natural consequence of “pedagogical” programme whose concept can be derived from Scruton’s writings: the culture of the highest values (including art that seeks beauty – no matter how much we do not understand it) teaches what we should feel – when meeting pieces of art we “exercise” our ability to empathise [13].

The philosopher answers the second question by referring to a false spiritus movens stereotype used by “imprudent optimists” as opposed to “prudent pessimists”. Modern idea of progress that is supposed to bring solution to all the problems became, according to Scruton, a common superstition. In keeping with this stereotype art has to be faithful to the spirit of the times, and if it shocks, it is because the receiver does not follow the inevitable progress: “a small dose of pessimism reminds us that exceptional art is not easy to make, that there is no readymade formula for it and that creativity makes sense only when there are rules of its limitation” [translated by Jakub Bujno] [14].

English philosopher never hid the fact that he is a believer in featuring art, especially figurative painting, lamenting that it was expelled from the world of art. He rejects arguments of modern critics about inadequacy presented by traditional means of expression, among which, crowning examples, the development of photography and media art, are effectively substituting “the old” techniques. Scruton claimed that a painter does not act as a photographer trying to immortalise the moment, does not point the camera towards the landscape, which could have looked differently than in the picture, a painter “tries to make sense out of it – not only from the perspective of perception but a spiritual one as well” [translated by Jakub Bujno][15].

Portrait

The beauty of man has unique nature. It is the beauty of a person and the body animated by the soul – in all its facets exhibiting its uniqueness. Scruton treats perceiving the face/person’s countenance with particular esteem. Though in question of human beauty there were many canons, in perception of most of the cultures eyes, lips and hands possess universal meaning as “they are elements through which the soul of a stranger manifests, allowing it to be cognised” [[translated by Jakub Bujno] [16].

In The Face of God we can find an ethical theory of face. Scruton was not an enthusiast of most widely known contemporary philosophy of face by Levinas; he shares only his conviction as to the ethical character that meeting other human’s face provides. Scruton accuses him of “deceptive obscurity” [translated by Jakub Bujno] and pessimism[17]. Among others, it might be the case of “experiencing the face as infinity”, defined in a different thinking than Christianity.

Scruton thought that it is very Christianity holds the best answer to all questions concerning human corporeality and the unique meaning of one’s face, with the answer being the embodiment[18]. Describing the remarkable place of the face in interpersonal relations he calls it, after Dante, “the balcony of the soul” [19] and persuades that man manifests in the world through the untouchable and sacred face. Is it not the answer in the spirit of Christian personalism?

The selected paintings indicate that a portrait is the most accurate illustration for dehumanising artistic measures – abuse of human body present in the modern art.

Francis Bacon, Głowa I (1948)

Francis Bacon was primarily interested in portraying a miserable, torn, lost human who, in his opinion, was an expression of the spirit of the times. This is why - a characteristic feature of this painter – disfigurement of the body and the face causing depersonalisation occurs.

Anthony Azisa i Sammy Cuchera, Dystopia (1994-1995)

Works of American duo Azis-Cucher from “Dystopia” series are a typical example of subversive measures that can be interpreted as a strong commentary to the pathological cultural situation of contemporary human or as an expression of said pathology, a mindless pixel play, which, in the case of human face photography, never passes unchastised.

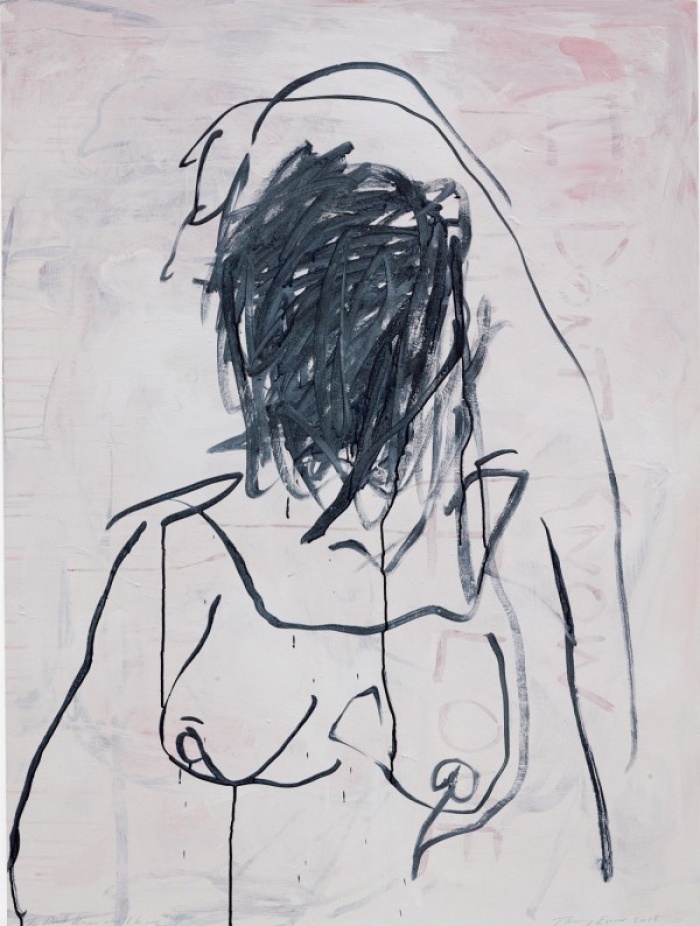

Tracey Emin, Nie wiem kogo kocham (2017)

Tracey Emin for years has been faithful to a kind of art called “confessional”, an emotional and exhibitionistic in its premise. She is accused of promoting violence, pornography and deviation. Or maybe the artist expresses her relentless depression and her works should be interpreted as psychological drawings?

Odd Nerdrum, Ocal kota (2016; fragm.)

In the context of the face sanctity, a questionable example can be found also in psychedelic painting of Odd Nerdrum, a painter praised by so-called “conservative critics”. The artist declaring his intention to paint “like Rembrandt” is a perfect illustration of the fact that technical excellence does not guarantee piece of art’s quality.

The English philosopher regrets that contemporary artists are so self-focused. He accepts art as an expression of self-understanding, yet not as a mindless and exhibitionistic self-presentation. Scruton does not want the artist to say “look at me” but rather “look at this…”, “look at his face”. Paintings from London Underground series by Lantian moved him as they provoke to look at fellow man with tenderness and care.

Epilogue

I believe that by advocating featuring art, understood as the one best suited to fill the requirements of beauty that was triumphant in the past, Roger Scruton got caught in a trap elaborately prepared by the contemporary world of art. Too strong attachment to certain conventions/poetics deprives even a friendly sceptic of arguments in discussion. One can distance to the choices Scruton made in the field of visual arts – ultimately, he was primarily a philosopher, musician, musicologist and a composer. Nevertheless, it is impossible to be indifferent to his reflections on beauty that emerges from a desire to be one with transcendence.

Scruton did not succeed in purely philosophical defense of beauty. A review of his arguments, selective by necessity, clearly shows that we are dealing with theological line of argument. Scruton tied the idea of beauty he wrote about with Christian view of the world[20].

Scruton, just like Shaftesbury, saw the world with enthusiasm, got amazed by what exists or rather, what existed and could have existed. His defence of beauty’s universality and need is a testimony to that. His educational programme is deeply inspired by Shaftesbury’s theories[21].

Their main idea could be summarised in the following way: 1. the judgement of taste (identifying beauty) can be taught if one was to act like a Platonian obstetrician by carefully helping a feeling/thought/recognition to be delivered; 2. If said process ends successfully, it brings significant spiritual benefits.

I have been always pondering whether I should consider the following, contrasting opinions equally – is it worth sacrificing life in search of truth, good and beauty or life has no meaning and truth, good and beauty do not exist? I am grateful to Sir Roger Scruton not only for an attempt at redeeming the world, but also for the following sentence: “A writer who says that there are no truths, or that all truth is ‘merely relative’, is asking you not to believe him. So don’t.” [22].

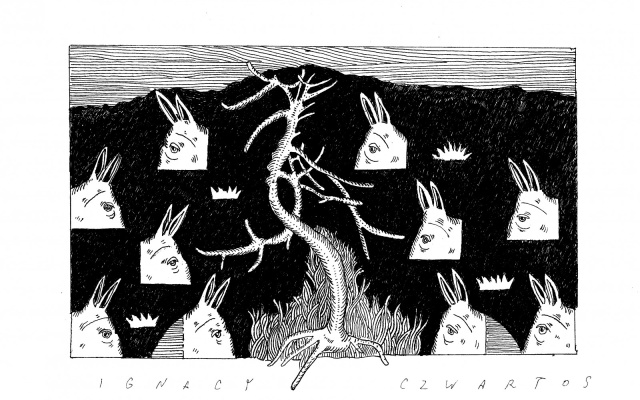

Drawing: Ignacy Czwartos

English translation by J. Bujno.

[1] Lantian D, artystka pochodzenia chińskiego, ukończyła studia magisterskie z zakresu sztuki medialnej i produkcji (MMAP) na UTS w Sydney. Popularność przyniosły jej obrazy przedstawiające w realistyczny sposób pasażerów londyńskiego metra. Była za nie nominowana do nagrody BP (National Portrait Gallery w Londynie); https://www.lantiand.com

[2]T. Oswald, An Interview with Roger Scruton, „Bentham Digest”, The Art Issue, 2020 https://www.ucl.ac.uk/philosophy/sites/philosophy/files/bentahmdigest_issue_3.pdf (dostęp 20.04.21)

[3] Scruton nie bez powodu używa słowa ultimate value (wartości ostateczne), na określenie wartości najwyższych. Nie można utożsamiać tego określenia z wartościami absolutnymi (również najwyższymi) ale wskazującymi na argumentację teologiczną.

[4] R. Scruton, Piękno. Krótkie wprowadzenie, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, 2018, s.14.

[5] R. Scruton, Tamże, s.34

[6] Por. Tamże, s.17.

[7] B.Gaut, Art, Emotion and Ethics, Oxford University Press, 2007, s.227-252.

[8]R. Scruton, Piękno, s.19.

[9] R. Scruton, Przewodnik po kulturze nowoczesnej dla inteligentnych, tłum. J. Prokopiuk, J. Przybył, Thesaurus, 2006, s.52.

[10] R. Scruton, Piękno, s.68.

[11] Tamże, s.27.

[12] Tamże, s.97

[13] S. Scruton, Kultura jest ważna. Wiara i uczucie w osaczonym świecie, Zysk i S-ka, Poznań, 2010, s.69-72. Oraz tegoż, Przewodnik po kulturze nowoczesnej dla inteligentnych, wyd. cyt., s.14-35.

[14] R. Scruton, Pożytki z pesymizmu i niebezpieczeństwa fałszywej nadziei, tłum. Tomasz Bieroń, Wyd. Zysk i S-ka, Poznań 2010, s.144.

[15] R. Scruton, Piękno i profanacja w: Muzyka jest ważna, tłum. Katarzyna Marczak, Wyd. Fundacja inCanto, Kraków 2020.

[16] R. Scruton, Piękno, wyd. cyt., s. 53.

[17] R. Scruton, Oblicze Boga, tłum. Justyna Grzegorczyk, Wyd. Zysk i S-ka, 2015, s. 98.

[18] Tamże, s. 222.

[19] Tamże, s. 104.

[20] R. Scruton, Regaining my Religion w: Gentle Regrets: Thoughts from a Life, Continuum, 2006.

[21] A.A.C. Shaftesbury, List o entuzjazmie. Moraliści, tłum., A. Grzeliński, Wyd. UMK, Toruń 2007.

[22] R. Scruton, Modern Philosophy, London 1994, cyt za: F. Fernández-Armesto, Historia prawdy, tłum. J. Ruszkowski, Wyd. Zysk i S-ka, Poznań 1999, s. 220.