As this text is being written, the exhibition Matejko. Painter and History [Matejko. Malarz i historia], which is seriously suspected of becoming another blockbuster, is being held in the National Museum in Kraków. The mysterious-sounding but most importantly English phrase blockbuster, traditionally used to describe blockbuster films, now becomes indicative of phenomena in the visual arts. Blockbuster is supposed to be about art exhibitions organized by ‘cash-greedy’ museums, which achieve attendance records.

The problem is that huge crowds of people (the people, the masses) want to see art in these museums. Yes, art precisely! And what is wrong with that? What is wrong is that it is not proper art, the only acceptable art, but rather some hand-painted pictures. The bad thing from the perspective of the epigones of 20th-century post-avant-garde/conceptual art is that these are exhibitions of painting, and usually figurative painting, which as a relic of the past was destined to be forgotten, which does not conform to the hard-won paradigms of modernity. The majority of the Polish public associates the word galeria [Pol. gallery, but also mall] with shopping malls, and critics argue that art that is universally liked cannot be good art and discourage people from seeing such exhibitions.[1] It is certainly not a sign of concern for the audience or freedom of artistic expression. It is about painting, but not painting in general, only a very specific one, because it is classical in form.

Blockbuster = bad art

The term blockbuster is a buzzword and does not stem from a research approach to the reality of art, but is used to label the phenomenon of the dynamic growth of interest in painting. No matter if it is an exhibition of Johannes Vermeer, Van Gogh or Tamara Łempicka, not to mention Matejko or someone contemporary like Beksiński or Duda-Gracz.[2] The mechanism of depreciation is simple: when we want to negate and destroy something or someone, all we need to do is repeatedly use a vague but scientific-sounding catchphrase without going into detail. However, the term blockbuster is inadequate to describe the phenomenon of painting exhibitions drawing crowds. The nature of the film business is quite different from the ‘business’ of the world of art. Today, big film studios make high-budget film products, backed by gigantic marketing, that are profiled to the right audience, while museums operate thanks to public subsidies. Exhibition blockbusters present art that is not the result of mega-productions and cultural marketing, but the fruit of the authentic experience of artists who have managed to remain independent. They present paintings that are created in the privacy of the studio, often throughout the artist’s life, which have stood the test of time and avant-garde iconoclasm. An art critic-curator formatted by the avant-garde, seeing the widespread interest in painting, must experience a nagging sense of helplessness, as thy are aware that, based on contemporary art, there is no chance to achieve a similar effect of blockbusters. To somehow mask the profound regression of art based on the dictatorship of modernity and to divert attention from the chronic voids in museums and galleries of contemporary art, they will gladly apply the catchphrase blockbusters or some similar term. Like an epidemiologist on duty, he will warn the public about the appearance of danger, shouting: blockbuster = bad art and you should not go there!

Art criticism has become marketing that promotes favoured avant-garde ideologies and innovative ‘aesthetics’ at the expense of objective analysis of 20th and 21st century artistic phenomena. The habit of a selective approach to current art locks art criticism in a bubble of its own ideologies, which deepens the separation of the contemporary art community from the facts of culture. The consequence of this is the disappearance in critics of the competence to deal with painting.

The enormous variety of media, techniques, narrative languages used in contemporary art, which is otherwise a good thing, makes it impossible to value with the same categories works from such different fields of creativity as installation and painting, fluxus and stained glass, for example. The formal and methodological incompatibility of contemporary works with one another, results in the impossibility of their reliable study by critics using only the criteria of the post-avant-garde. If, for the evaluation of a contemporary realistic painting, we apply the criteria and requirements used for performance or installation, rather than criteria specific to the field of painting, then painting is set lose in this struggle as an ideologically incorrect, non-innovative work. The otherwise interesting concept of intermediality of the arts has led to an expansion of the definition of painting, to ‘dilute’ it among new media art, to the point of undermining its autonomy. For contemporary critics and curators, the classical language of painting remains beyond their competence and therefore cannot be of interest, relevance and value to them.

The phenomenon of visuality in art

The topic of blockbusters becomes a good excuse to think more deeply about the current phenomenon of traditional painting. Despite the strenuous efforts of the leftist art wold to convince audiences of post-avant-garde art, one can see a great interest in classically understood painting. Its contributors are the general destruction of visual culture proposed by the anti-art trend[3] and the state of saturation and exhaustion of our civilization with electronic media and pixelated screen images. The atrophy of the visual sphere, aesthetic clumsiness and poor colour palettes of the products of modern art, which stem from programmatic aestheticism, tend towards subtlety in painting. Moreover, the artificial environment of human life in the city, filled with ubiquitous advertisements and even kitschy graphics generated by artificial intelligence algorithms, intensify the longing for the traditional, ordinary image, for contact with the physical matter of the work, for the craftsmanship of the object that allows for prolonged reading and quiet meditation. Painting is an alternative to fast photography, mass printing, ephemeral pictograms, which neither reflection nor the emotional sphere of man can keep up with.

Painting, when classically understood, remains the most visual branch of the visual arts at all times. It ascends to the highest possible level of visual sublimation in art. It is not about the media spectacularity and intensity of vision and projection, but about the depth, complexity and remarkable subtlety of the painterly language. Visual perception of the physical morphology of a painting, from the substantiality of the paint, which ensures the non-trivial impact of colour, through the speech of spots, textures, compositional structures, the possibilities of symbolic narration, ending with the suggestion of the inner space of the painting – all this makes up the language of traditional painting, which, despite requiring a high degree of visual sensitivity and aesthetic refinement, attracts many artists and viewers.

The utopian criterion of novelty has tyrannized the natural visual experience in art and the aesthetic needs of a large group of people. Modern painting in the twentieth century no longer refer to vision as the primary tool for exploring the world. Today, the modern artist’s eye is closed, detached from nature, and does not explore the truth about the visual aspects of reality and the facts of human existence (at most, it watches screens and follows the Internet). On the other hand, the closed eyes of experts generate a widespread belief that painting with a classical idiom based on pure visual experience has become obsolete, and if it even functions somewhere, it cannot be officially counted among the contemporary visual arts.

Let us try, as an experiment, to suspend all avant-gardism with all its derivative ‘ism’ post-styles. To invalidate its methodology, dogmas, myths, phobias – not to return to the state before it existed, but to see what the reality is, what exists in art today beyond it. A universal, common, vivid current of painting with a classical idiom, based on simple visual experience, is then revealed to our eyes. A trend that has continued uninterrupted since prehistory and antiquity, and today is even growing spectacularly around the world. Modernist iconoclasm is just a small episode in the history of art and civilization, which is dying in agony before our wide-open eyes. One can easily understand the state of frustration of the attitudes of the avant-garde circles, as the existence of modern painting based on pure visual experience undermines the whole point and effort of the aesthetic revolution in the 20th century, especially since it was supposed to be an ultimate experience. I will try to demonstrate this later in the article.

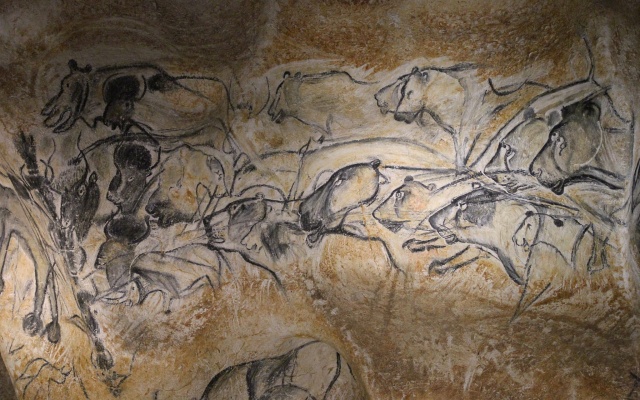

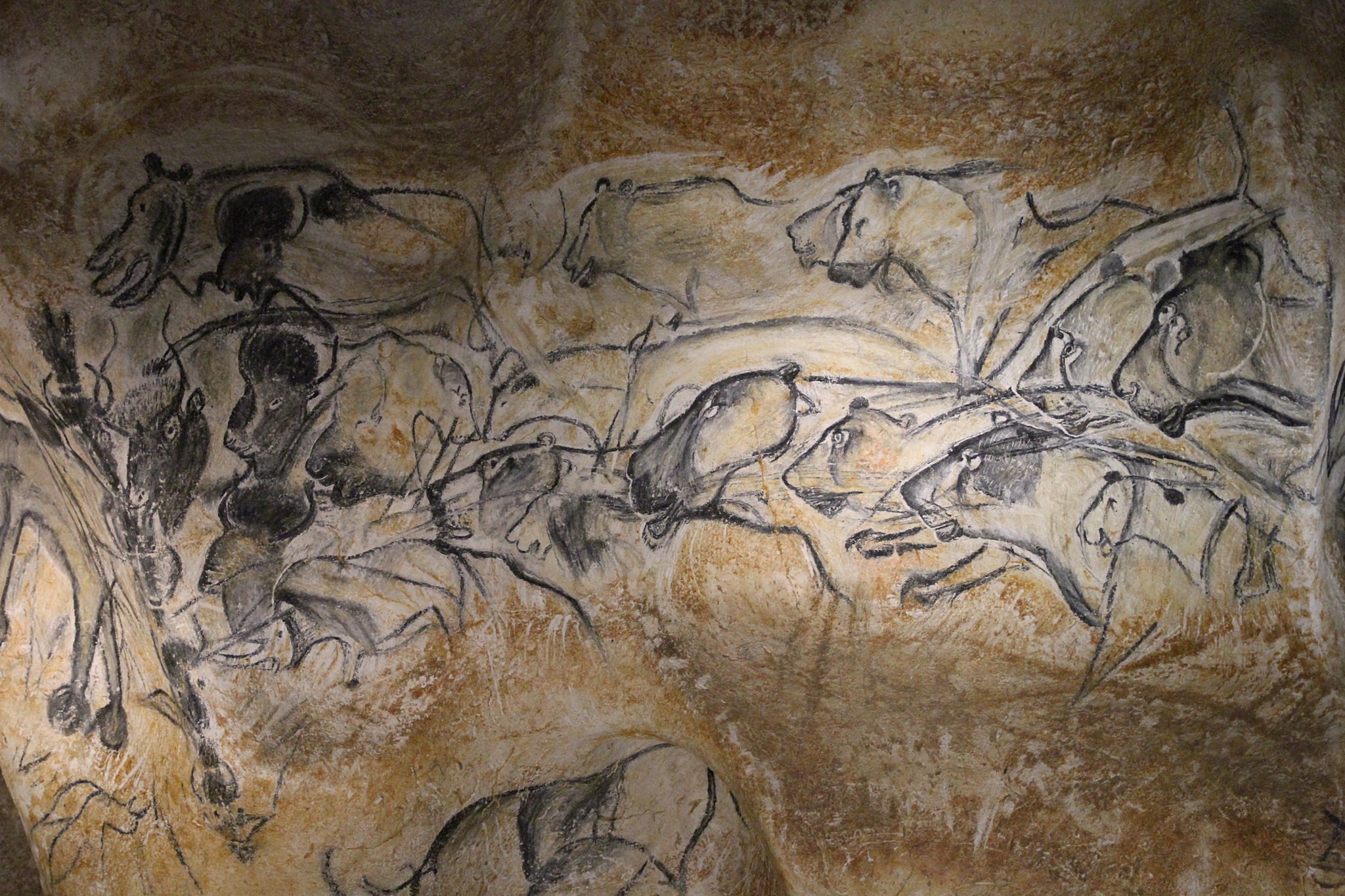

Chauvet Cave, 30,000 - 32,000 BC. France

https://commons.wikimedia.org

Meanwhile, classical painting, based on pure visual experience and often in the convention of radical photorealism, persists and develops around the world.[4] There are regions where the classical traditions of painting have never been interrupted. Examples include the Netherlands, Germany, the US, Canada, Italy, Sweden and Japan. Artists such as Edward Hopper, Grant Wood, Lucien Freud, Matthijs Roling, Odd Nurdrum, Michael Triegel continue the classic traditions of imagery. Poland has also seen a great return to so-called figuration, especially among the young. Many noteworthy artists do painting based on visual experience. I could name at least a few dozen of them whose works are worth showing in contemporary art centres. Let me mention, for example, Andrzej Maciej Łubowski, Łukasz Korolkiewicz, Jerzy Mierzejewski,Tadeusz Boruta, and quite young Agnieszka Nienartowicz, Karol Palczak or Mateusz Orłowski.

Painting based on visual experience has already been referred to by many terms in the history of art, such as mimeticism, realism, hyperrealism, verism, naturalism, figuration, but also academism, impressionism, symbolism and even expressionism. [5] However, the names mentioned above refer more to the theme, style or iconographic type, indicating historical eras and styles, and do not depict the general methodological principle of image creation, which is based on visual sensation. Especially when we want to talk about contemporary phenomena in painting, they demand various epithets and linguistic combinations, such as: new figuration, neo-realism. When speaking about painting, I shy away from popular buzzwords like realism and figuration, because they no longer mean anything, are completely exhausted, misleading or narrowing. The word figuration, for example, takes on many professional-sounding but meaningless terms: refiguration, defiguration, pseudo..., post... Examples of such a wordplay are exhibitions: Prefiguracje at Forum Gallery (Toruń 2014), Refiguracje at Baltic Gallery of Contemporary Art (Słupsk 2023), Rzymskie figur racje at Zachęta Gallery (Warsaw 2023). With the stereotypical pigeonholing of the reality of art into rigid categories: old and new art, the use of any of the above words causes confusion. Moreover, the prevailing avant-garde-conceptual mentality, generally hostile to painting, generates accusations of undoing art and returning to historical styles on the basis of these terms.

The lack of a uniform term for the universal visual method that has always been used in painting prevents communication and reliable research of relevant phenomena in current painting. In order to define the universal trend in painting, whose methodological principle and creative inspiration is simple visual experience, I propose the term reality painting, which expresses the artists’ focus on the visible aspects of the reality of the world. The term can be further broadened as reality art. It is inspired by the title of the Kraków exhibition of contemporary Dutch painting Painters of Reality, Contemporary Dutch Figuration [Malarze rzeczywistości, współczesna figuracja holenderska] (2004), which presented paintings by 38 Dutch artists from the collection of the Drents Museum in Assen and the collection of the ING Group.[6] The term reality painting is free from connotations of the past and historical styles and indicates a visual method and relates this broad trend in art to classical, affirmative philosophy and the concept of truth about visible reality.

Philosophical dispute over reality in art

At the core of every art direction or artistic style is a specific philosophical doctrine relating to truth, which determines the perception and understanding of reality and the way to interpret the visual experience. Theories about art and the figure of its creator stem from philosophical settlements and condition the concept and form of an artwork. The basic feature of painting’s centuries-old heritage is its affirmative attitude to visible reality, which distinguishes it from the avant-garde conception of art. In my opinion, it is the attitude to the phenomenon of vision that generates the main dividing line in today’s art and culture, which is most evident precisely in the field of painting.

The very word truth raises intellectual confusion and cognitive controversy in today’s world. According to the leftist-oriented discourse, the concept of truth is to be considered repressive and exclusionary, thus unacceptable. The classical understanding of art is intrinsically linked to truth and one of its features that is beauty. Hans-Georg Gadamer writes:

‘Plato calls beauty that which flashes and attracts, which is the visibility of the ideal. What so shines through everything else, what has such a light of convincing truth and rightness in it, is what we all perceive as beauty in nature and art, and what irresistibly arouses our approval: “That is the truth”.’[7]

The admiration of the beauty of the world is a philosophical statement by itself, with reality painting as its material equivalent. The contemporary trend of reality painting is an authentic reaction to the visual, but also spiritual experience of the truth of reality and human existence, which stems from logocentrism.[8] The antithesis of this is the negation of truth and objective reality in favour of subjectivity (atheism, dialectical materialism, Marxism, post-modernist concepts of chaos), resulting from anthropocentric (actually egocentric) philosophy. Hence it follows logically that post-avant-garde art (surrealism, various forms of abstractionism, Dadaism, minimalism, conceptualism, etc.) is detached from visible reality and must, by virtue of its revolutionary genesis, fight against classically understood art based on visual experience. The expression of this struggle is the negation of mimeticism.[9] Avant-gardism, in the name of the 19th-century modernist belief in mechanistic progress in art, along the lines of the industrial-technological revolution, made it a common but absurd objection to painting. Mimicry considered a naive goal of art was to enslave the artist and force him to depict the world as he sees it. Painters know that it is impossible to depict the world in a perfect way in a painting, as interpretation will always creep in. Just try to ‘recreate’ what we see, and you will immediately fail due to workshop deficiencies and limitations of the material. Nevertheless, even photography does not show the world as we see it, but distorts it in its own specific way, especially in terms of perspective and colour. Even if we obtain in the image the fidelity characteristic of photography, surely no one will mistake such a work of art for nature itself. Mimicry is not the goal of painting, but only a means of depiction, a method, a convention for creative expression that makes the image communicative. Practice shows that mimicry is indeed enslaving, but only to untalented, weak artists who are unable or unwilling to learn from what they see.

From the artist’s egocentric (egotistical) focus on themselves and closed to the visible aspects of the world comes another antithesis of reality painting, which is abstraction.[10] Abstractionism suspended the universal visual experience in favour of formal operations with materials and means of expression in painting (formalism). Behavioural expression, psychological states, the subconscious, emotions and conceptual operations within the work became the source for the painting. However, the rigid division of painting into figuration and abstraction is perpetuated in post-avant-garde art, where no divisions apply and everything is supposed to be dependent on inter- and multi-media. Separating the basic visual qualities at the disposal of a painting, such as abstractness and the potential for figure allusion (figurativeness), and then juxtaposing them is a dialectical method of excluding and destroying one of them. And so abstractionism became a method of destroying the iconicity of painting based on natural visual experience. In theory, one assumes the equality of the two attitudes in painting, but practice shows that the widespread phobia of mimicry and the complex of modernity, make it automatic to favour abstractness over so-called figurative painting. Abstraction is regarded as a higher level of development in terms of art consciousness. This is no longer officially declared today, but all cultured people are supposed to know it. The modern viewer often does not identify with abstract art, in which they do not recognize the truth about the world or themselves. Unable to identify with the image, they reject it as false.

Abstract painting compositions, multiplied ad nauseam, despite their visual appeal and declared mysticism, affect only the emotional sphere. The records of complex formal combinations and the lack of any narrative or anecdote make the picture hermetic and unintelligible. Abstraction is uncommunicative and inaccessible to the viewer’s intellect, which constitutes a serious impoverishment of the possibilities of the language of painting. The programmatic negation of painting based on visual experience results in the solitude and alienation from the world of culture of many people who are sensitive to colour, to painting matter, to anecdote in a painting. The fight against painting is ultimately a fight against reality: against the essence of man and against the truth of their aesthetic needs in physical, emotional and spiritual dimensions.

Reality painting

The artistic output of ancient, modern and currently created painting confirms that the natural visual experience has always been exclusively sufficient for the creation of great art. Reality painting is the art of the pure eye, without electronic prostheses, unconstrained by ideologies and paradigms. It is a genuine, spontaneous, even ‘ecological’ reaction resulting from the awe of the phenomenon of visibility, available to anyone who has not yet lost his sight. As early as 1973, Jerzy Nowosielski said:

‘the essence of the image will not change. It will remain the drawing of definitive conclusions from the observation of reality – both external and internal.’[11]

Psychophysiological visual experience in painting based on the interpretation of visible reality, on the experience of nature, man and the products of civilization was, is, and will be a universal methodology of the language of painting, independent of the era, culture or region. The changeability of the world, as well as the development of civilization, guarantees us constant visual changes, which is a novel and inexhaustible source of inspiration for reality painting. Hence, reality painting boasts a remarkably broad range of formal, stylistic and thematic possibilities. Most importantly, it overlooks the artificial division between old and new art.

The future of painting depends on liberation and opening your eyes to the world. The return to the phenomenon of vision in art opens up a new field of exploration in the visual arts that has been blocked for several decades. The synthesis of the historical traditions of painting together with the experience of current (contemporary) painting, enriched with conclusions from the achievements of anti-art, creates a particularly interesting area of creative and research issues for artists, philosophers, art theorists and sociologists.

One must dare to say what many painting-sensitive viewers, but also many artists, think about art. It is worth talking about painting, beauty, truth and figuring out what it is really about. It is worth taking the risk of boldly traversing the vast expanses of reality, guided by the sense of sight supported by faith, intuition, and the inner light. It is worthwhile in painting to return to contemplating reality, a kind of ‘here and now’ of the world, everyday life and the ordinariness of human existence, including all material and visual manifestations of our civilization (the category of affirmation and awe is, after all, excluded from good contemporary art). An artist practising the art of reality can constantly update his artistic experience in a fresh manner, interpret and express it in any style and form. This was done excellently by, for example, Jan Matejko, and nowadays by Odd Nurdrum, whose paintings are currently on display at the CSW Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw.

Strangely enough, exhibitions that showcase works of painting art are labelled as blockbusters. The crux of the problem turns out to be that people yearning for authenticity, truth, beauty, enjoy reality painting, which was not supposed to exist. In a huge part of modern society, it evokes a strong and extraordinary aesthetic experience that pulls the strings of the soul, causes a metaphysical experience of pure beauty, but also a sense of meaning and truth (truthfulness).

Since painting in its ancient and traditional form survived early medieval and 20th-century iconoclasm and conceptualism, since it persists and thrives despite the invention of photography, film, digital graphics, 3D media and, more recently, artificial intelligence, it does not seem that anything can ever be capable of excluding it from popular culture in the future. The only threat to reality painting may be the total enslavement of societies and the restriction of the artist’s margin of personal freedom, by means of legal constrains based on detached, totalitarian ideologies. What is needed in art is not the ideology of modernity and paradigms, but freedom and material means for talented and hard-working artists. Fortunately, it is exactly the individual artist, not institutions, that sets trends and stages in the development of art.

[1] Dlaczego cały świat wali na Vermeera, a cała Polska na Łempicką. "Muzea jak hollywoodzkie studia". in: Gazeta wyborcza 05.05.2023. [accessed on: 25.08.2023]

[2] A reference to the author’s column Truizmy i tautologie, czyli sztuka obrzydzania sztuki [Truisms and tautologies, or the art of making art disgusting]. Obieg 2023.08.03 [accessed on: 26.08.2023]

[3] Kiereś H. Spór o teorię sztuki. (1997) pp. 68–69 and 71

[4] Cf. Bigaj-Zwonek B. (2017). Zwrot figuratywny. Realistyczne tendencje we współczesnym malarstwie polskim, in: Przemiany. W kręgu kultury polskiej XX i XXI wieku, pp. 155–183

[5] The issue of the difficulty of defining realistic painting can be traced back to W. Tatarkiewicz in his book Droga przez estetykę (1972).

[6] Fryz-Więcek, A. (ed.) (2004). Malarze rzeczywistości. Współczesna figuracja holenderska. exhibition catalogue. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie.

[7] Gadamer H. G. (1993). The Relevance of the Beautiful. p. 20

[8] Andrzej Miś says: And so, by logocentrism I will mean the view that there is (although hidden under the shell of phenomena) a definite order in the world, that reality is rational, permeated with logos, which makes itself available, reveals itself to the thinking man (not to everyone and not immediately, of course). Miś., A. Zasada hierarchii, in: Przegląd Filozoficzny — Nowa Seria 1999, R. VIII, Issue 1 (29), ISSN 1230-1493

[9] The importance of mimesis in art is explained by H. G. Gadamer, who, in his book The Relevance of the Beautiful, writes: ‘There is a kind of imitatio in every work of art. Here, mimesis does not, obviously, mean imitating something already known, but bringing something to representation so that it is present in sensory fullness. [...] What I mean is that tradition, I believe, is right when it says: “Art is always mimesis,” i.e., it makes something represent itself.’ p. 48.

[10] An analogy can be made between the importance of abstraction as a method in painting and Karpiński’s reflections on the role of abstraction, through which we want to know the social being, as expressed in the book: Kryzys kultury współczesnej in the chapter: O potrzebie nowej filozofii, especially pp. 100–101 with footnotes.

[11] Nowosielski J. (2012) Sztuka po końcu świata. Rozmowy. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Znak, p. 8