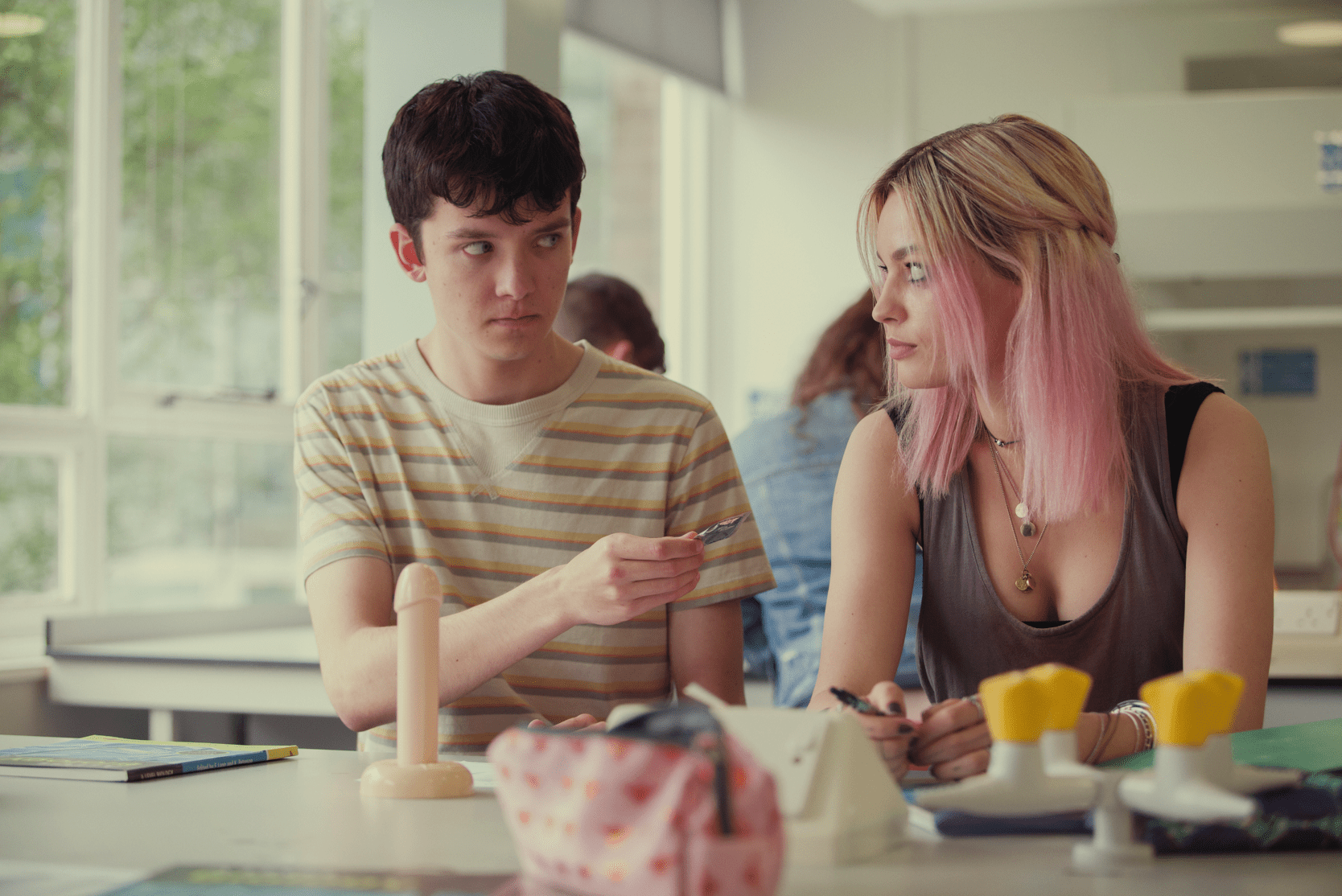

Ideal plans for Friday evening? A warm blanket, a bowl of popcorn and the most favourite TV series’ premiere on Netflix. It is a way to forget for a moment about pop quizzes, upcoming tests, an argument with your schoolmate or various other school-related stresses that teenage life revolves around. The school education gives way to TV series education which, under the disguise of the escapist entertainment and much desired break from daily life hardships, hides a power to influence young people and shape their forming characters. The power that appears veiled, imperceptible even, but perhaps way more effective than endeavours made by teaches at school. And most definitely involving very limited parental and social control. If any at all. Let us take a closer look at how one of Netflix’s biggest hits does it – the British TV series, Sex Education (2019-).

Netflix: materiały promocyjne

A broad range of productions dedicated for teenagers (widely known under their terse term of teen drama) and their incredibly high viewing rate on popular streaming platforms point to a simple conclusion: teen dramas do sell. Young people want to watch their peers (or rather – as it is usually the case – actors in their late twenties that pretend to be their peers) and problems of daily lives they can relate to. School friendships, first loves, sexual initiation, difficulties in parent-child relations, problems with being part of a peer group, decisions about their future career path or looking for their own identity – cocktails of the same motifs are served by subsequent productions that take place inside the school walls. Those brave enough touch on heavyweight subjects such as various addictions and traumatic experiences (molesting, rape, death or suicide). A relatively huge number of productions decides to use youth environments in stories that draw inspiration from genres like crime fiction or thriller, including stories that adopt supernatural elements (horror, science-fiction or fantasy).

Americans are obviously in the lead in the area of record-breaking TV series for young people, though there is an increasing popularity of European productions drawing handfuls from USA narration factories; their patterns, types of heroes or iconography. American schemas were a stimulus for a British production of Sex Education – the series creator, Laurie Nunn, openly admits being heavily inspired by cult movies of the eighties by John Huges (The Breakfast Club, Sixteen Candles and more) that started the genre so popular today.

Although I mentioned series’ hidden “education”, Sex Education does not seem to be fitting the schema – the didactical dimension of the production is mentioned in the very title after all. Regardless, getting familiar with three seasons that were released so far and the analysis of the values promoted by the series, as well as the vision of the world it presents, lead to conclusions including much more than the sexual education alone. And these conclusions are very alarming.

Initially, the series places sixteen-year-old Otis in the foreground, though in the second and the third season the creators put more emphasis on a collective and explore the motifs concerning other pupils in the school that our main character attends. Otis grows up raised by his mother – a renowned sexual therapist – who equipped him with a vast knowledge on the topic of human sexuality. At school, Otis realises that it is not a common knowledge at all and it is greatly desired by his male friends who experience first sexual encounters. Together with a rebellious female friend Maeve, Otis becomes a school’s first sexual counsellor. The fact that Otis has never experienced his own sexual or romantic debuts brings a new flavour to the situation.

It is not hard to imagine that the activity of students’ sexual “clinic” becomes a point of departure for the study of a wide range of problems, questions and doubts that teenagers with little experience in such an area stumble upon. The series’ educational activities are carried out with adorable charm and most amiable mood – in the spirit of breaking cultural taboos which – according to the creators – turn out to be the main source of misunderstanding and difficulties that affect different spheres of our lives. And, yet, that is just sex alone.

Netflix: Promotional Materials

And it would be difficult to pick on something in the production if that were the end. It is obviously harmful to assume that absolutely everyone in high school has sex, a belief zealously promoted in the series. Even those, who had some doubts at the beginning quickly join the group of clients of the sexual counselling. The person who decides on abstinence is asexual, which for young people watching the TV series is equal to the message that sexual initiation simply has to take place in high school. Knowing this hyperbolic aspect of productions for teenagers where everything is somewhat “larger than life” (starting from the number of guests at home parties and ending with the intensity of colours present in students’ fashion) a lot of parents would assume that this tone could be acceptable. Especially because Sex Education distinguish itself from all other productions of this kind with its creation of fleshed-out, psychologically deep characters.

Yet, as the series’ story continues, a message masterfully crafted by the creators is gradually emerging and in the last episodes of the third season it becomes a form of an ideological manifest making its way into unaware minds of teenage viewers.

At one point, TV series promoting so called “positive sexuality”- in its various manifestations – begins to play the role of a guide through consecutive colours of the rainbow flag which is discovered by teenagers experimenting with sex. Step by step, character by character, their identity is defined by sexual preferences discovered in bed (or in a school’s toilet). Along with self-definition comes the expression of adopted identity in the outside world.

In the third season, the new director takes over Moordale High. At first, she poses as a leader who is properly modern and open for a dialogue with students but, over time, she slowly reveals her true purpose of bringing lost order to the institution and bringing the end to “sex school” bad reputation, a nightmare in the paperwork. To make her malicious scheme work, she introduces a new set of threatening rules.

Teenagers’ patchy clothes are changed to dull uniforms, she has their colourful lockers painted grey and lines are drawn in the middle of the floors, a measure to help organise traffic in school corridors. Merry songs of uncensored kind and with heavily implied sexual content sung by the school choir (Fuck the pain away by Peaches) are replaced by Latin song Non sibi sed toti (which translates into “Not for oneself, but for all”). Concerned and startled pupils observe as the list of bans start to appear on the school walls (prohibiting smoking, running, having piercings in the nose, dying hair etc.) along with (to their great dismay) the list of values to be fostered during their time in school. These include: focus, persistence, discipline and respect. Sounds scary, right?

Netflix: Promotional Materials

Obviously, new rules spark resistance. Why students identifying themselves as non-binary should wear uniforms that assume binary division? Why the joyful creativity of next generations of teenagers, who paint new versions of genitalia images on one of the walls, should be gone? The new director will stop at nothing to punish and humiliate those, who do not obey the new rules. The culmination of her efforts seem to be the introduction of “the wrong” sex education where abstinence is promoted and the teachers threaten their pupils with unwanted pregnancies using videos from births.

The very meaning of the TV series is determined in an episode where the creators decide to juxtapose problems of contemporary youth with their peers of previous generations. During a school trip to France, pupils visit war trenches, cemeteries, read about history and look at the photos of those, who gave their lives for the things they deemed most important. For their freedom and identity. For community they held dear. It would seem that such a contrast of generations should somehow inspire the rebellious youth to reflect on triviality or, perhaps, oddity of their school problems in the face of what life looked like for their peers dying in trenches. Nothing could be further from the truth! Teenagers’ conclusion is quite the opposite – following the example of previous generations, they too have to fight for their identity.

But what is the identity of the contemporary teenager according to Sex Education creators? No one at this point has any illusions that it would have something to do with community centered around national or religious values. These were burnt down by the fires of modernity in the presence of common multiculturalism. They were replaced by the freedom of the individual understood as an unconstrained expression of individualism. The expression of identity, whose one of the basic components is sexual identity, powered by a pin with a rainbow flag, reinforced with pride of one’s own preferences in bed. Any form of declining one’s self-expression is seen as oppression and thus (as set by the example of former generations) it has to be fought against.

It is at that stage when disturbing, or dangerous even, message of the TV series comes into full view. Since we do not accept the tiniest interference in self-expression we manifest in our surroundings and we cannot make compromises that could improve the way society we live in functions, then no social contract can be made. No deals and no cultural or moral constraints are possible as they are forms of oppression. There is no concept of a “group” anymore. There is no community. Instead, there is a collection of snowflakes, proudly demonstrating their diversity, holding hands only to culminate in blowing up their community. That is exactly what happens in the series. Rebellious teenagers start the revolution which does not only chases the dreaded director away but also has the investors withdrawn and, as a result, the school has to be closed. Despite everything, students have the feeling of moral victory. They stood for what is important and defended it.

Netflix: Promotional Materials

Though, in theory, Sex Education is rated PG16, it is easy to find internet forums of kids fascinated by the show who are a couple of years younger than this age limit. Yet, no one is surprised. Who could expect Netflix hits’ creators to stop pursuing new records of worldwide box office in favour of parental control? After all, why should modern parents control a streaming service which is popular all over the world? And there is nothing we can do to prevent children from growing up so soon. However, the question remains: what will the world shaped by people raised by such TV series education look like? The very people who would answer a famous Polish “Who are you?” nursery rhyme… how, indeed?