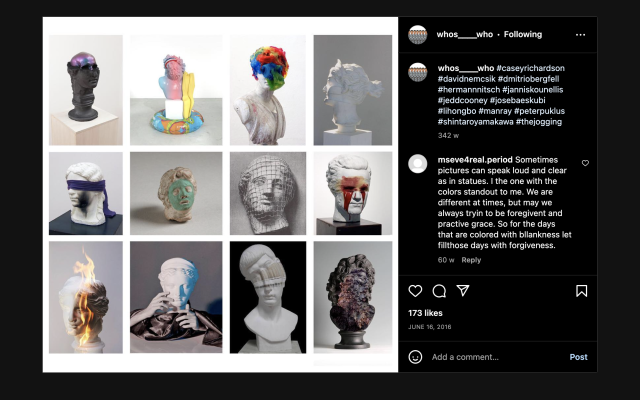

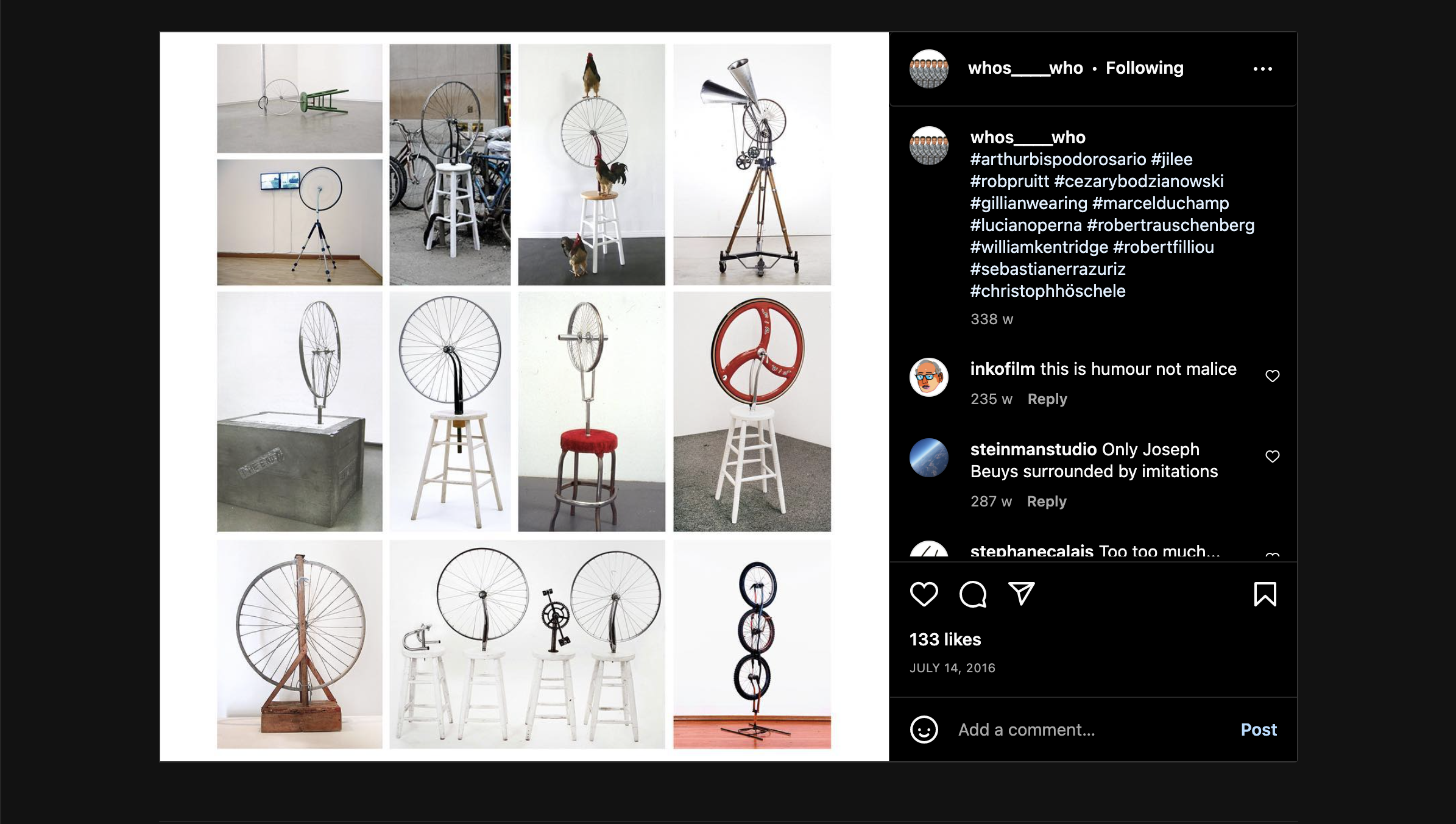

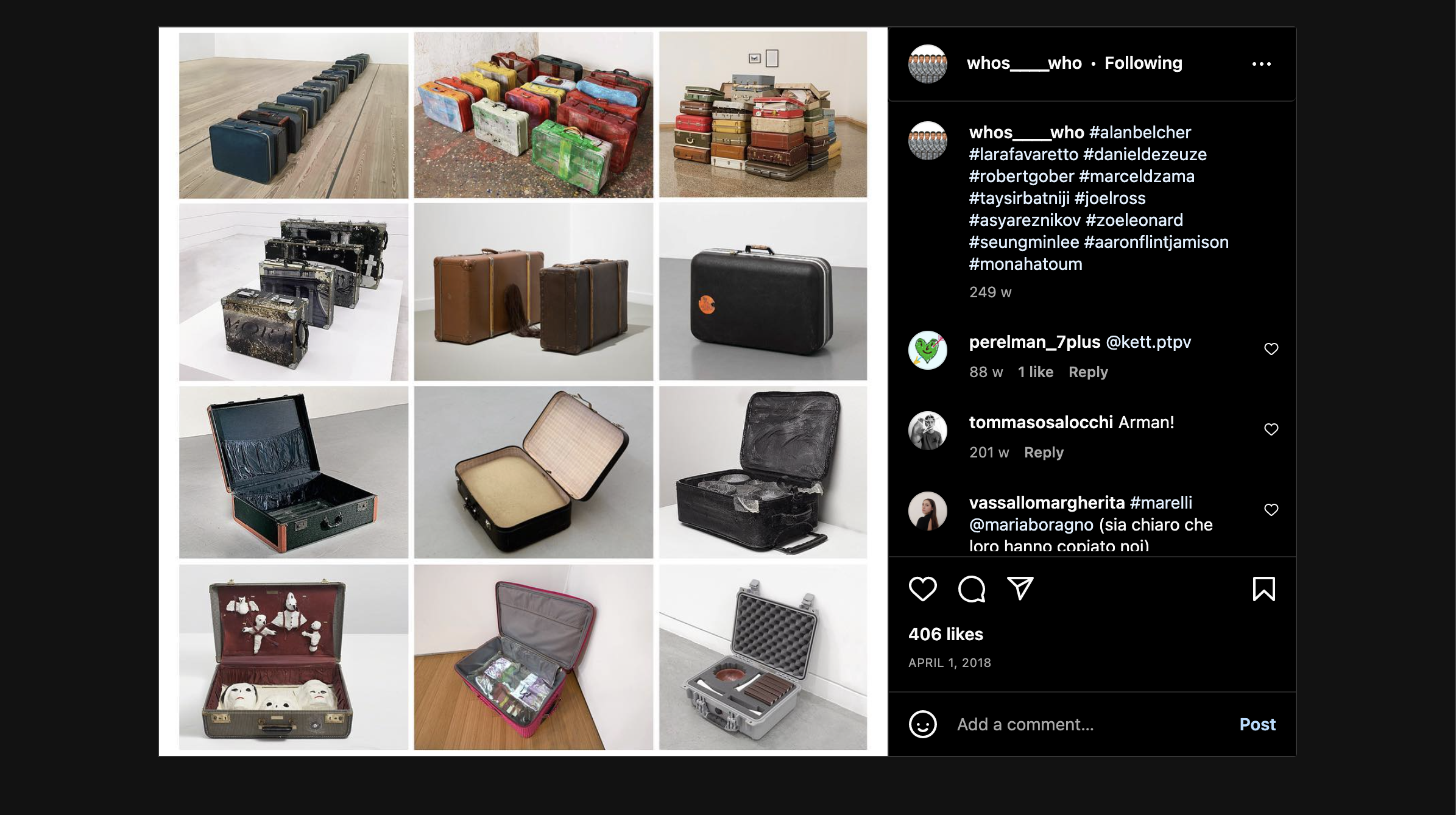

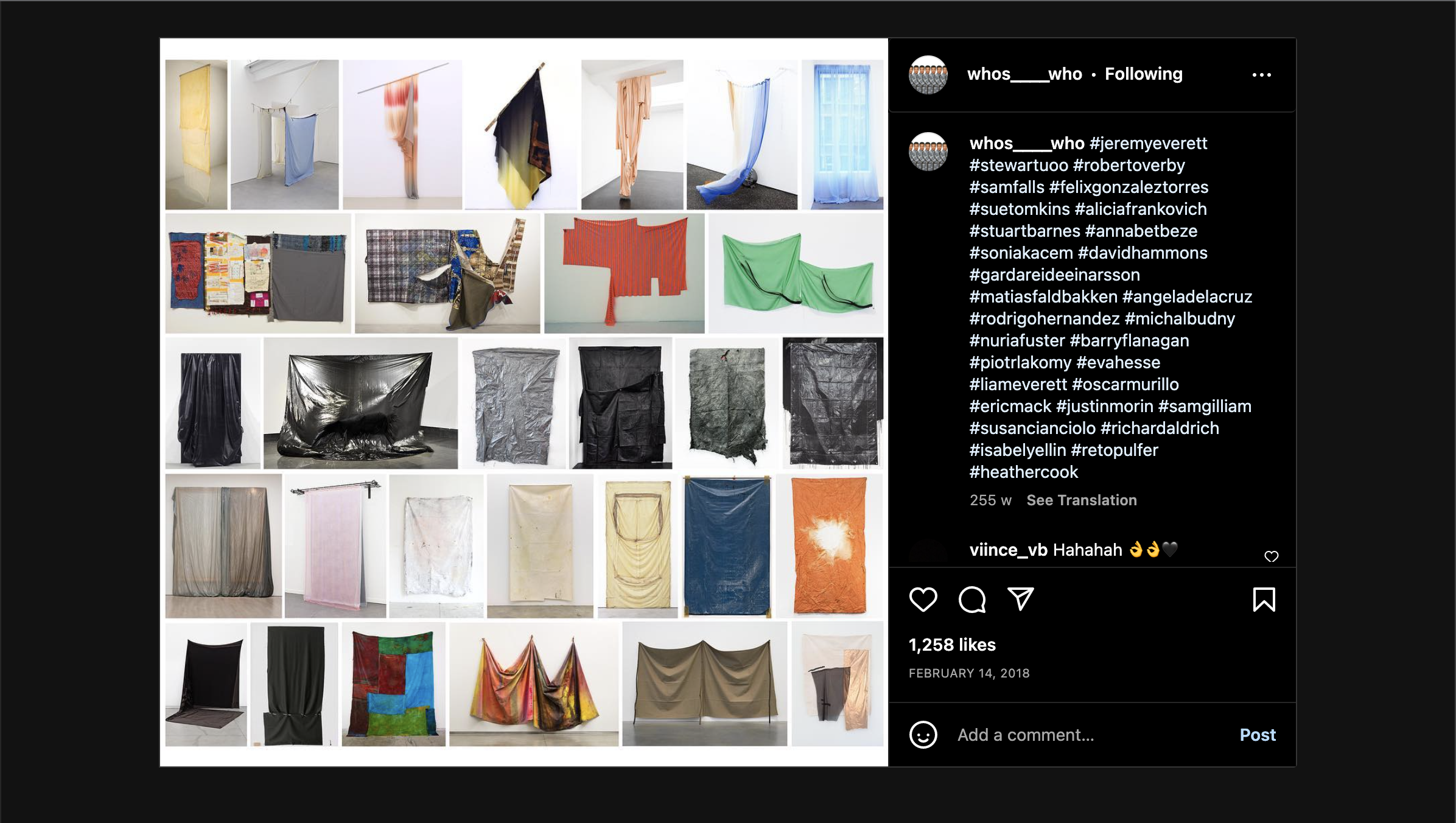

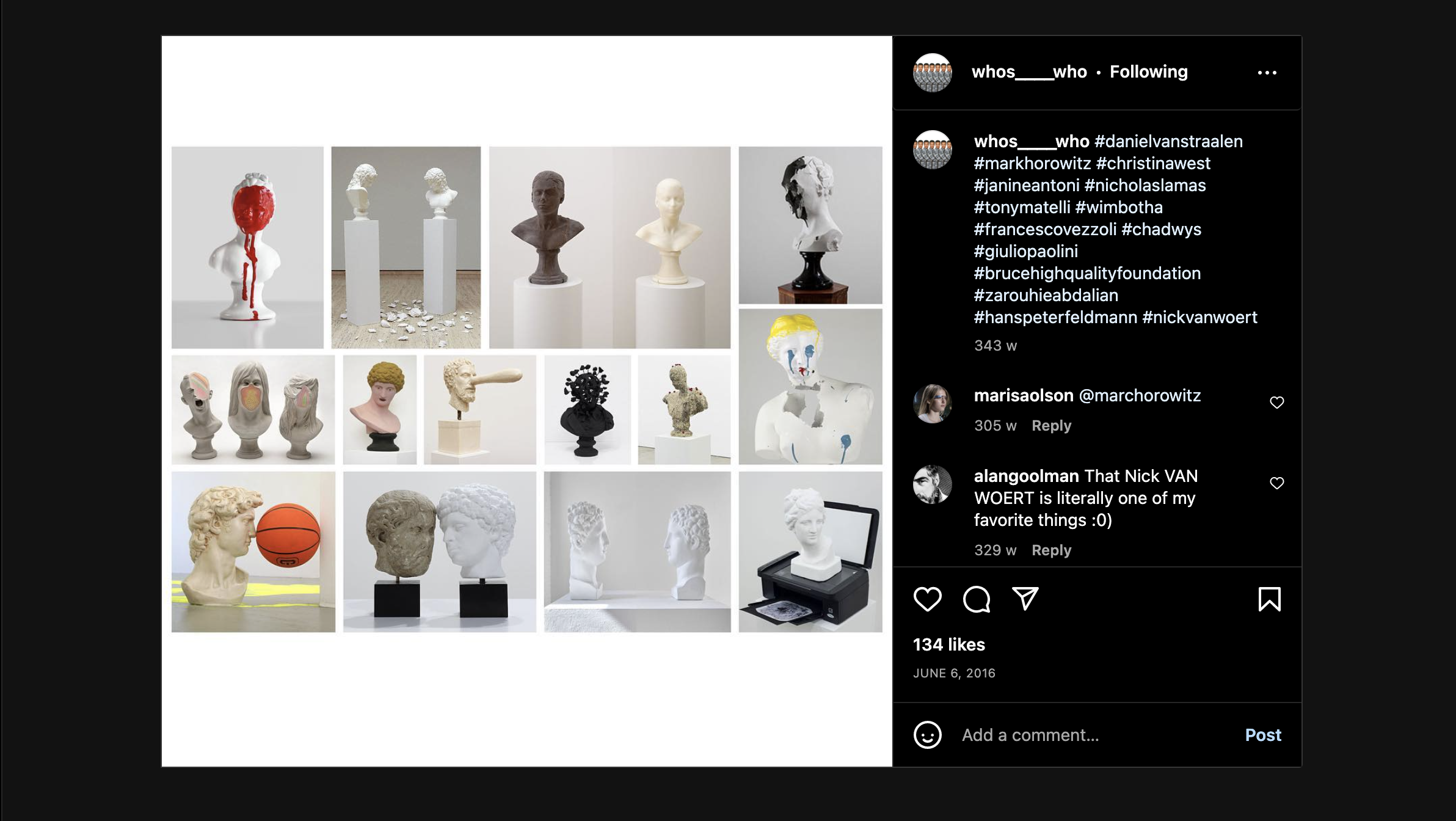

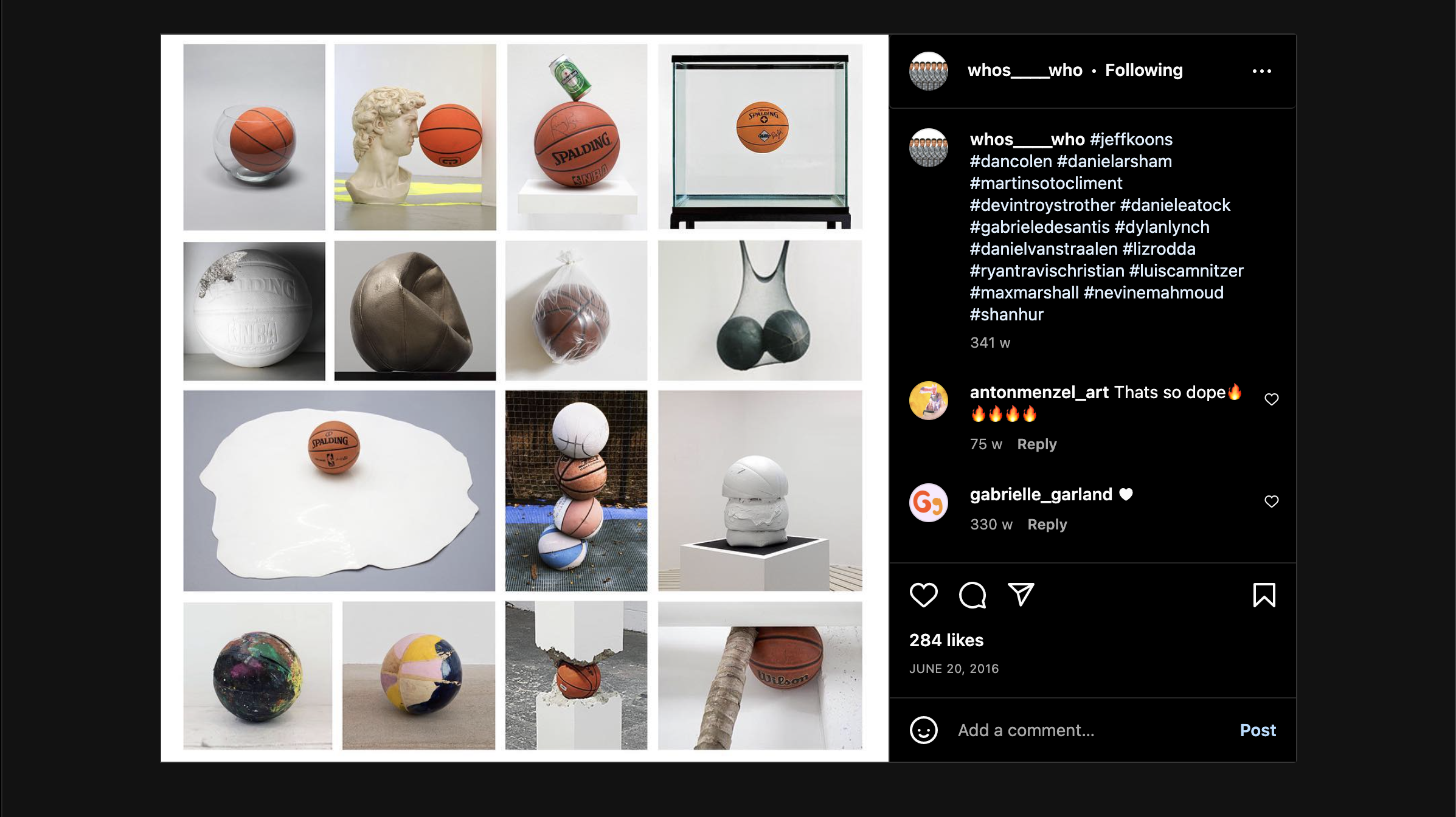

These days it is entirely possible to enter a contemporary art museum and see pieces which are interchangeable from one another. And online, anonymous critics have noticed, such as the Instagram account whos____who. But how did we get to this point? Why do so many contemporary artworks, and some would include Modern Art as well, share similar aesthetics and sensibilities regardless of their geographical location and artist's practices? Much can be said about the influence of global art markets managed by a relatively small number of curators and art dealers globally but highly present in London, Basel and Hong Kong. Similarly, the current model of the Art University has absorbed most of these aesthetic and political sensibilities; it is not the purpose of this piece to investigate who extends the most influence on who.

Most critics will agree that a cultural phenomenon wrecked through the Arts and Academia simultaneously. Some will champion this shift as it opened up an endless amount of critical cultural applications referred to broadly as "intersectionality." This method is employed in academic and artistic practices where subjects must consider multiple degrees of analysis. It often aims to highlight injustice and even campaign for political change. Others in the cultural sphere, mainly self-referred as classical liberals or conservatives interested in aesthetic values, have denounced the application of such theories emerging from Academia as disastrous for the state of politics and aesthetics alike. Many contemporary commentators that engage in what is referred to as the culture wars, perhaps Jordan Peterson, the most eminent in recent years, will employ terms such as Postmodernism or even cultural Marxism to describe the political demands of their opponents.

Yet, Postmodernism is broadly agreed to have started in the 1950s with the Western Intelligentsia coming to terms with the catastrophic outcomes of the Second World War, specifically the attempts to rationalize in objective terms the Holocaust and the application of the Atomic Bomb. The theoretical framework of these disasters was blamed on Modernism's quest for truth, harmony, and objectivity, combined with Eastern philosophies and disdain towards the bourgeois classes that dragged them into this conflict. The avant-garde movement DaDa, specifically the work of Belgian artist Marcel Duchamp, anticipated much of the postmodernist and intersectional practices in academic theory from the 1950s onwards. More specifically, I suggest Duchamp as the first, and perhaps last, true postmodernist artist whose artworks between 1917 and 1922 have set the blueprint for all pieces that appear these days in Museums but also some of its most overused selling points.

As an attempt to return to classical liberalism values, and make a case for free speech and Universalism, some of the most prolific critics of Postmodernism have for years referred to this phenomenon as cultural Marxism. These critics appeal to reason and the scientific method and invoke the Enlightenment as the most successful attempt at encapsulating these values, to which they argue we should return. However, at its conception, Marxism was not an attempt to diagnose what we may refer to these days as cultural studies; this came later. Marxism originated as an attempt to establish the historical theory of how history unfolds as a result of changes in the material forces and how they affect multiple classes of people, which may collectively organize and exercise their political agency to assert their freedom over exploitative working measures. Marxism criticizes capitalism in maintaining that it may have produced unprecedented wealth. Still, it has yet to accomplish universal freedom and create enough material wealth to enable individuals to free themselves from selling their labour.

Indeed, many European academics and Avant-Garde practices have absorbed Marxism. Still, many theorists are blamed today for setting up this analytical framework that originated between the two World Wars. These academics and critics, now referred to as The Frankfurt School, warned against and, in some cases, even perished at the hands of totalitarianism movements across Europe. They also scrutinized the arts and popular media and their application by Totalitarian Movements for propaganda purposes. Their inherent suspicion and concerns with popular culture can be justified by the application they witnessed during their times. Walter Benjamin may be the most famous theorist emerging from what is now referred to as the Frankfurt School, but Theodor Adorno also formed a part of this association which discussed the arts and advanced the framework for academic disciplines liked with Postmodernism. Perhaps a better definition should be "Critical Theorists," with multiple and intersecting spheres of applications, with some patterns of dissecting and critiquing ideology combining Marxist theory, Freudian Psychoanalysis, Philosophy and Politics. Academia established this discipline in the 1950s, rediscovering these thinkers and propagating their research methods and theoretical points.

First, the argument must define what art is and what the legacy of Duchamp's practices rebels against to this day. Art results from a combination of practised, knowledgeable skills that produces something not present in nature, hence the term artificial, which merges material and abstract notions. It can be seen as a fundamental human activity, as a way to shape our environment via our mental world. Skills are passed through tradition and down generations as techniques and ideas change. Art Historians and Critics also note the district between craftsmanship and liberal arts, work produced by free men as opposed to slaves. The quest for Universalism sparked by the Renaissance also included medicine and architecture as art practices. Liberal arts came to refer to the activities with the mind, the abstract, and the ideas, also defined by class and status, versus the actions that materially deal with everyday objects and products, craftsmanship. Many of the names of this craftsmanship are lost to history, and the artist's persona has always swung between anonymous labour to designs refined by education. Vasari speaks of the lives of the artists in one of the first historical art accounts in the western world. He describes the practices and the lives of eminent painters, sculptors and architects. Vasari established the theoretical framework for the Renaissance. Paint is a practice that involves pigments, canvas, plastics, and wood, they are messy practices, and it's also a contested field between craftsmanship and the highest form of intellectual insight. When taking into consideration hierarchies of values in terms of quality, importance and worth of an artwork or an artist's legacy, we adopt perhaps conservative notions, such as the ones of Roger Scruton, of the importance of aesthetics, the sacred and a shared public vision of the importance of the distinctive virtues and national expressions. Many would argue that the entity of the Modernist period is a race towards a shared truth, achieved via a traditional, rational and enlightened culture. Postmodernism is a reaction to certainty and this pursuit. It adopted the principle of the impossibility of going backwards after the shocks of WWI. It is not built on the purpose of reason. It announced the death of the collective and the rise of the individual, movements that emerged as a result, from literary to visual arts, are anti; they are not an art movement. They are seeking to destroy its intellectual and institutional framework.

As the shocks of horrors of WWI ravaged Europe, a group of writers and artists were congested in Zurich for Switzerland's political neutrality and gathered in Cabaret Voltaire, setting the framework for what was to come for Modern and Contemporary art. From this group emerged the Avant-garde movement named DaDa, after a word that was meant to be nonsensical. Dada was committed to the subversion of reason, and meaning in art, literature and life, which they agreed were some of the instigators of WWI. They were anti-art. He is an anti-artist who rejected art and the notion of aesthetics, institutions, achievement, academies, biographies and the whole industry revolving around it. The monetary value attached to art and the Establishment of Art Academies were also rebelled against as they sought to destroy its intellectual and institutional framework. They sought to not legitimate their gestures as a coherent and ambitious movement. In contrast, the Surrealists, a group established in Paris by Andre Breton and Georges Bataille, regarded themselves as artists and were serious about their intentions. They aimed to set up a movement whose theoretical framework was inspired by Freudian Psychoanalysts, New Popular media such as photography, film, and Marxism. Unlike DaDa, the Surrealist sought relevance and, at its conception, argued for freedom via the logic of dreamwork. But what DaDa achieved, especially with the gestures of Duchamp between 1917 -1922, became a framework endlessly reproduced to this day. With Duchamp's infamous 1917 Fountain piece, which he signed with a pseudonymous R.Mutt and a wrong date, Duchamp produced the most important modern art piece of the 20th century according to a poll of the run-up to the Turner Prize in 2004. An artwork that still makes an endless amount of online articles and books on its impact.

The Urinal is very much contested, and disputed interpretations emerge every year. This object is presented with multiple layers of meaning; first of all it is produced by a non-artist or a persona, and it is a commercially and industrially produced object that is turned upside down, which will set forward the conceptual art practice that employs found objects and commercial products as Readymades. The Fountain also assumes an abstract notion as it is elevated and presented as a foundation. Finally, it is a mockery of art institutions and their quest for canon and legitimacy. These are only five layers of interpretation that can be read into this gesture, but more interpretations are to be expected by scholars and critics alike. There is more. Duchamp has also produced kinetics, musical happenings, short films, moving sculptures, optical illusions, and sexual satirical cartoons with his 1919 L.H.O.O.Q, which features the image of Leonardo Da Vinci's Mona Lisa, with this title and a moustache. The title is a play on phonetics that sounds as if one says, "she's got a hot bottom." A similar play on word emerged when Duchamp presented himself in what today could be called a gender-bending persona named 1920 Rrose Sélavy, a female persona that appears in a photograph shot by Surrealist artist Man Ray.

After the period mentioned above, 1917 - 1922, Duchamp appeared bored with the art world and his provocations and dedicated the rest of his life to playing chess. From the 1960s onwards, art historians and critics have discovered and theorized about his gestures. Many conceive of him as the grandfather of Pop Art, Happenings and Performances and Surrealism. His anti-art had become an institution in itself, and without pointing out single artists and their practices, it is self-evident that what Duchamp achieved is a framework, like his readymades, to produce a standardized approach that combines subversion, provocation and social awareness. Focus on the Aesthetic element of art, its transcendental beauty and even the societal need to attempt this was entirely discarded and ridiculed. Many artists today do not consider whether their productions will result in anything that one may find beautiful. In 1964 a Milan Gallery hosted an exhibition named "A homage to Marcel Duchamp (Omaggio a Marcel Duchamp)", curated by Arturo Schwarz. Concerned with the loss of some of the original readymades produced by Duchamp, Schwarz suggested the artist make copies and sign them with ~its~ his real name. Critics have pointed out how by doing so, Duchamp subverted his own work and the notion of being nonsensical by setting the framework to celebrate his legacy, an idea he would have rejected at its core during his first years as an artist. These days, all pieces present in MoMa or Tate Modern and worldwide are a replica conceived by Schwarz and Duchamp. This notion adds a meta layer to the previous lists of possible interpretations of a piece such as the Fountain.

Again, it would be pointless to discuss the singular piece of Contemporary artists with this theoretical background as visually documented whos____who's critical perspective is without such theoretical explanation and perhaps makes the case even better than this piece. Similarly, literary critics and historians may as well produce a similar argument concerning literature, as the doom and horrors of WWI shell shock many, such as T.S Eliot, which in 1922 details a similar cultural Wasteland. Artists live in Duchamp's shadow, and museums set themselves up for failure when presenting contemporary gestures as subversive or counter-cultural. The conception behind these acts was a complete rejection of the industry of credentials and legitimation. The art world still manages to cause controversy when a conceptual piece is sold for astronomical figures of old master paintings that are dealt with internationally in the Art Market. Perhaps contemporary artists should free themselves from looking for provocation, irony and shock. It is also possible to make the case that such gestures have failed to impress the public and attract curiosity to the art world. Is it possible to make the case that abstract art attracts a large crowd, and is it not confined to the theoretical notions that require expertise in critical theory? Moreover, can an artist today produce an object for beauty and perhaps even transcendental ideas? Is there any value in continuing a legacy based on reaction and rebellion