In the 1980s, Janusz Bogucki, a prominent Polish art critic and theorist and a charismatic curator, presented uncensored and politically incorrect independent exhibitions of contemporary art outside the official art circulation – mainly in Warsaw’s churches. He initiated his elaborate multi-component and multi-genre presentations during martial law, amidst a boycott of the art institutions operating at the time and a social ostracism towards artists exhibiting their work in state galleries, which was sometimes interpreted as collaboration with the communist authorities.[1]

Słownik polskiej krytyki artystycznej XX i XXI wieku states that Bogucki’s approach was marked by an excellent insight into the Polish artistic milieu and, at the same time, by a fine intuition for global trends in art. He saw theoretical reflection and artistic practice referring to various, often exotic, religious and cultural traditions as an important field of reference, especially in his late period of activity.[2]

Janusz Bogucki (1916-1995) is sometimes compared to the iconic Swiss curator Harald Szeemann (1933-2005), who invented the ahistorical concept of the artist’s individual mythology and initiated an innovative understanding of an exhibition as a self-contained work of art, in particular when interpreted textually within the framework of the linguistic turn in art.[3]

Paul Thek, Ark, Pyramid (1971), installation [5 m x 14 m x 45 m], Documenta 5, 1972, Kassel;

curator: Harald Szeemann. Photo: Brigitte Hellgot © Estate of George Paul Thek & Documenta Archiv.

A reconstructed body of art

Szeemann created more than 200 exhibitions, such as Documenta 5: Questioning Reality – Pictorial Worlds Today in Kassel (1972),[4] and two Venice Art Biennales (in 1999 and 2001), including the memorable 49th edition titled The Plateau of Humankind. Considered by many to be a turning point in the history of twentieth-century art, his exhibition Live in Your Head. When Attitudes Become Form, held at the Bern Kunsthalle in 1969, showed site-specific works by sixty-nine European and American artists from the conceptualist, minimalist, postminimalist, land art and arte povera movements. The problem was that few managed to see it. After 44 years, the exhibition was reconstructed at the 2013 Venice Biennale by influential Italian curator Germano Celant, who coined the term arte povera in 1967 to describe the second most famous Italian twentieth-century art movement next to Futurism.[5] Welcomed enthusiastically by professionals and the public alike, the exhibition was reconstructed in every detail in collaboration with Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas (OMA studio in Rotterdam) and German artist Thomas Demand. The exhibition of young revolutionary artists of the 1969 generation was restored like an archaeological object; according to Celant, artistic director of the Fondazione Prada, the Venice exhibition was not to be read as a fetishistic celebration of a certain period of imaginative dynamism but rather as a ‘readymade à la Duchamp’.[6] The full-scale recreation of the white spaces of the 1918 Swiss exhibition building was placed amidst the baroque frescoed chambers of the eighteenth-century Venetian palace Ca’Corner della Regina on the Grand Canal, purchased by the Milan-based Fondazione Prada. From 1976 to 2010, the palace hosted the historical archives of the Venice Biennale, which have found a new home on the mainland, in the Marghera district. Meanwhile, the vast archives including the enormous library that belonged to Harald Szeemann himself (accumulated over decades of work in his 2,700 square metre Fabbrica Rosa studio in the Italian-speaking canton of Ticino) were purchased in 2011 by the Getty Research Institute from Los Angeles. As reported by the Los Angeles Times at the time, the documents stored in as many as 1,000 cardboard wine boxes could have covered eight football fields.[7]

Paul Thek, Ark, Pyramid (1971), installation [5 m x 14 m x 45 m], Documenta 5, 1972, Kassel; curator: Harald Szeemann. Photo: Brigitte Hellgot © Estate of George Paul Thek & Documenta Archiv. [Pictured on the right: the famous 1967 work The Tomb, sometimes incorrectly referred to as The Death of a Hippie, which was exhibited many times in various arrangements and then destroyed in the early 1980s]

Part of the interdisciplinary public exhibition Znak Krzyża (Sign of the Cross), featuring the Polish artistic elite, prepared in 1983 by Janusz Bogucki and Nina Smolarz (architect by education, photographer and journalist by profession), was reconstructed in Warsaw in 2022 in the Sigismund Room at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre of Contemporary Art (which is a reconstructed early Baroque building from the time of Sigismund III Vasa) for the group exhibition Nie ocenzurowano. Polska sztuka niezależna lat 80. The curator of the historic exhibition, painter and art critic Tadeusz Boruta, was an active participant in the events of the time.[8] For Bogucki, the main intention behind the Znak Krzyża project was as follows:

[...] to show the presence of this sign both in contemporary Polish art and in our lives, traditions, customs, and at different levels of culture. It was meant to be a consciously undertaken similarity to the confused languages of imagination from Documenta 5 in Kassel

and

[...] to show the scope of meanings that are associated with the sign of the cross today: from a completely secular consideration of the form itself, through various symbolic senses to religious Christian symbolism.[9]

Bogucki described Documenta 5 in Kassel as follows:

It was a sociological panorama of the phenomena that are regarded as artistic in different circles and on different tiers of white man’s culture (along with the latest innovations of the avant-garde of the time – such as the archives of conceptualism and the paintings of the American hyperrealists – it showed works of television advertising and political propaganda, strange neo-Dada objects, garden gnomes, gaudy devotional articles and teens’ pop stamps, as well as blueprints for a future civilisation, the works of the mentally ill and many other things).[10]

The choice of venue in Warsaw for this innovative artistic manifestation took a long time. Successive locations considered, such as the churches near the New Town Market Square and then the headquarters of the Association of Polish Architects in Foksal Street, proved unsuitable. Finally, the exhibition, prepared in the context of the second pilgrimage of John Paul II, the Intellectual Pope, to Poland (16-23 June 1983) took place from 14 to 30 June 1983 amidst the rubble of the Divine Mercy Parish on Żytnia Street, which was destroyed during the Warsaw Uprising and was under construction for the previous 10 years due to being rebuilt in a social action by local residents. The condition set by the host community – Father Wojciech Czarnowski and the parishioners – was that the construction workers should be allowed to work freely during the preparation of this extensive site-specific artistic realisation. Consequently, as the curator recounted, the largest two-storey space of the old church, housing the paintings and the large spatial arrangement of Jerzy Kalina’s Ostatnia Wieczerza built on a pile of rubble, was divided by a wheelbarrow path for transporting sand and rubble from the depths of the presbytery outside, as though some sort of ongoing happening.

Having spent long weeks in contact with this architecture in statu nascendi, the artists were reassured that ‘[...] their work should be a natural complement to what is being created here’ ‘respecting every relic of the parish’s life as one respects the trees on a construction site’. The presence of the objects of art was to emphasise ‘the character of the great nave raised from the ruins of the church and of the underground labyrinth of narrow passages, dark chapels, and brick pits’ and ‘side caverns’.[11]

Janusz Bogucki’s archives collected in his spectacular art studio on the top floor of a skyscraper in Fabryczna Street in Warsaw, where he worked surrounded by a unique collection of works of contemporary Polish art, and then handed over to the Institute of Art of the Polish Academy of Sciences have gone missing through an unfortunate coincidence.[12]

Szeemann and Bogucki referred to the exhibition and artworks using organic metaphors. Szeemann argued that it was necessary to ‘travel between studios, from one original artwork to another, in the hope that one day they will grow into an organism called an exhibition’[13], whereas Bogucki claimed that symbolic objects and objects of art ‘fuse with architecture to form living wholes resembling organisms – the opposite of artificial sets such as a collection, an exhibition, or a stock inventory’.[14]

Paul Thek, Pyramid. A Work in Progress (1971), installation, Moderna Museet, 1971, Stockholm; curator: Pontus Hultén. Photo: Erik Cornelius © Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

The curator’s gesture

‘Harald Szeemann has defined himself as an Ausstellungsmacher, a maker of exhibitions. There is more at stake in adopting such a designation than semantics,’ writes the influential Swiss curator and art critic Hans Ulrich Obrist. Szeemann is more conjurer than curator – simultaneously archivist, conservator, art handler, press officer, accountant, and above all, accomplice of the artists.’[15] In the Mind Over Matter interview he gave to Obrist in Paris in 1995 for the New York Artforum, Szeemann remarks:

The intensity of the work made me realize this was my medium. It gives you the same rhythm as in theatre, only you don’t have to be on stage constantly. You had to improvise, to do the maximum with minimal resources and still be good enough that other institutions would want to take on the exhibitions and share the costs. [When in the 1980s the Kunsthalle became more structured and the exhibition program was reduced,] with this slower pace came institutional pedagogies, restoration, and guards. In the 1960s we had none of this. For me, if there was a pedagogy, it was about the succession of events; documentation was not important.[16]

At the Attitudes exhibition, Szeemann concludes:

The Kunsthalle became a real laboratory and a new exhibition style was born – one of structured chaos. (...) But the most important thing about curating is to do it with enthusiasm and love – with a little obsessiveness.[17]

In the documentary about the independent cultural movement of 1981-89, shown during the Nie ocenzurowano exhibition at the Centre of Contemporary Art, Janusz Bogucki says:

We didn’t even want to use the word ‘exhibition’. In museums, galleries, and showrooms, art is displayed as a specific artistic product and only as an artistic product. Well, our work was somehow guided by the idea of the return of art, the return of creativity from this sphere of separation back to the Home and to the Temple as two places which, in the tradition of all cultures, dealt not with the specialisation of man in this or that skill or ability but with his spiritual maturation as a whole.[18]

His artistic environment arose from the conviction that faith and artistic creation have a common origin, ‘born in the flow of the same primordial energy. This energy is divine love, which has led the universe away from nothingness and whose spark, latent in the depths of every human being, makes them a person created in the image and likeness of the Creator.’[19] He pointed out that in ancient, pre-modern cultures there was no difference between things sacred to the artist and things sacred to man.

The above figure of the visionary curator, who does not so much show artworks as stage – like a theatre director – site-specific processual artistic endeavours in close collaboration with living artists, refers to the idea of dialogue and teamwork within an artistic community, temporary as it may be. A true visionary curator becomes an artistic medium in their own right; however, they must also be an outspoken personality and a skilful and authoritative mediator in constant deliberations and negotiations with artists who are invariably attached to their individualism, freedom, and autonomy.

Paul Thek, Pyramid. A Work in Progress (1971), installation, Moderna Museet, 1971, Stockholm; curator: Pontus Hultén. Photo: Erik Cornelius © Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

French minimalist Daniel Buren appeared uninvited at the upcoming exhibition When Attitudes Become Form, rejected the space offered to him by two of the contributing artists, and covered the hoardings around the Kunsthalle in Bern with 8.7 cm wide vertical strips of paper (his artistic signature). He was subsequently arrested and had to leave Switzerland.[20] When invited to Documenta 5, Buren was very critical. ‘He said curators were becoming super-artists who used artworks like so many brush strokes in a huge painting.’[21]

Janusz Bogucki mentioned that the Znak Krzyża project crystallised slowly and was preceded by a long stage of meetings and community discussions, consulted with counterculture sociologist Aldona Jawłowska. At the very outset, professional support from psychodrama professionals was even considered. What was important was the very idea of an ‘ecumenical conversation’, which was a direct response to the spiritual situation of the ‘veterans of the conceptualising avant-garde of that time’ with the intention of ‘overcoming the aggressively competitive way of being and the spiritual foundation of this aggressiveness so strongly linked to the enduring tradition of the avant-garde’.[22]

The idea for the Attitudes exhibition emerged during a curatorial search in the Netherlands. In Szeemann’s words:

[In the studio, Jan Dibbets] greeted us from behind two tables – one with neon coming out of the surface, the other one with grass, which he watered. I was so impressed by this gesture that I said to Edy [Eduard Leo Louis (Edy) de Wilde, director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam], ‘Okay. I know what I’ll do, an exhibition that focuses on behaviours and gestures like the one I just saw.’[23]

The notion that art and the sacred are intrinsically linked was concretised during Bogucki’s stay in Chartres in January 1958:

At that moment, I realised that we need a different syntax. [...] The co-existence of the changeable and the eternal is experienced at Chartres at every moment through the vibrancy of light in the stained glass windows. This is due to the changing of the seasons, the times of day, the vagaries of the weather, the wandering of clouds in the sky, even the movement of trees swayed by the wind. One sits there as if in a giant space cavern and gazes into these stained glass windows, which then cease to be glass, decorative work, symbolism, or iconography, and turn into pillars of the human spirit, formed from coloured light, something like a materialised and pulsating prayer that has been going on there for centuries.[24]

The curator’s creative artistic gesture may be interpreted by referring to the notion of the ‘gesture of creating’, which is a central concept of the philosophy of culture associated with the existentialism of Vilém Flusser (1920-1991). The gesture of creating is an everyday gesture of every human being. ‘A gesture is a movement of the body or of a tool connected to the body for which there is no satisfactory causal explanation.’[25] Flusser emphasises that we instantly ‘read’ gesture. From the slightest movement of facial muscles to the most powerful movements of masses of bodies called ‘revolutions’, we intuitively read the symbolic world of gestures of the surrounding coded world. ‘The word “gesture” itself etymologically comes from gerere meaning something like “acting”; and what is history by us, was called things expressed by gesture, res gestae, by the ancient people.’[26] Inspired by phenomenology, Marxism, neo-Kantianism and the philosophy of dialogue, Flusser saw the essence of originality or creativity ‘as the ability to combine anew what is already known’.[27]

Paul Thek, Pyramid. A Work in Progress (1971), installation, Moderna Museet, 1971, Stockholm; curator: Pontus Hultén. Photo: Erik Cornelius © Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

For Flusser, the world of culture is the only world available to man understood as a dynamic project (and not as a finite entity), who, as assumed in neo-Kantianism, ‘is constantly conversing with himself’ and remains in communication with the other person;[28] he speaks through language, which is the most basic structure of the human world, forming the basis of reality.[29] At the same time, when creating culture, man never starts from scratch; in dialogue with the past, ‘no writer has ever encountered a virgin language,’ writes Flusser in his essay Does Writing Have a Future?. ‘The process of writing is a thousand-year-old discourse that has continually produced new information and for which every writer is a dialogue.’[30]

Imposing form on chaos, the gesture of creating is a fundamental way of being in the world of man, who is always striving for perfection: homo faber (the maker, the man of work) is in fact the creator, the artist. Although in everyday life people do not see most of their gestures of creating as artistic, they all involve fabrication, and therefore in a way constitute art.

Even when we are tying our shoelaces or filling a pipe, we are doing something that we believe art is all about: changing the world by arranging objects into new forms. This is not about recognising ‘Art’ with a capital A in such modest gestures but rather the opposite: that these gestures are recognised when looking at art even in its most magnificent form. We then witness the gesture of a frustrated search for perfection.[31]

Flusser, in line with Plato’s view, believes that an artist working in the public sphere is, like a politician, someone who does something to be exhibited in public. However, unlike Plato, Flusser connects the two activities of art and politics because of their common ground in that they direct a certain ideological message to their audiences; he definitely rejects, Plato’s contempt for art and politics as domains of praxis leading to opinions that are the opposite of wisdom.[32]

Paul Thek, Pyramid. A Work in Progress (1971), installation, Moderna Museet, 1971, Stockholm; curator: Pontus Hultén. Photo: Erik Cornelius © Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

In the context of the widespread contemporary artistic activity practised as anti-art, Flusser argues that it is possible to restore the lost meaning of the term ‘art’ as a search for the truth about human existence:

[...] it can, to some extent, be unearthed from under the deep layers of garbage accumulated over the last five hundred years (and which is called ‘progress’).[33] [...] There is something archaeological to that gesture, like digging for buried treasures or for lost skeletons and fossils. It is like the activity of anti-progress: it advances in the direction of the past, of the roots we come from. It is a ‘radical’ activity in an etymological, (and therefore strict), sense of that term [from Latin radio – ‘root’] Being a search for what has been lost, or forgotten, or covered up [...] it is a search for ‘truth’ [...]. In this (and other) aspects it is the exact opposite of ‘artistic activity’ in the modern sense of the term (which is progressive, futuristic, and favours fantasy and imagination).[34]

Structurally, the gesture of creating consists of a series of gestures developing in successive phases: the gesture of perceiving, the gesture of grasping and exploring, the gesture of comprehending, the gesture of producing, the gesture of understanding, the gesture of making, the gesture of creating, the gesture of making tools, the gesture of realising, and the gesture of presenting, or offering, which is the gesture of love.

As they present their work, the hands offer themselves to another. They expose their work, making it public. The gesture of presentation is a political gesture. [...] There is also a general atmosphere of the gesture of creating: an atmosphere of a violent search for perfection in the objective world for the sake of the other, a search that ends in loving resignation.[35]

Paul Thek, Pyramid. A Work in Progress (1971), installation, Moderna Museet, 1971, Stockholm; curator: Pontus Hultén. Photo: Erik Cornelius © Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

A curator without an institution?

Harald Szeemann resigned his post as director of the Kunsthalle in his hometown of Bern in 1969 amid scandal; the Swiss capital’s parliament and the gallery’s programme board, composed mainly of local artists, became involved in a violent dispute over the gallery’s programme.

Paul Thek, Pyramid. A Work in Progress (1971), installation, Moderna Museet, 1971, Stockholm; curator: Pontus Hultén. Photo: Erik Cornelius © Moderna Museet, Stockholm

As a result of a controversy, Janusz Bogucki resigned in 1974 from his position as manager of the renowned Galeria Współczesna located in the lounge of the Empik International Press and Book Club in the monumental classicist building of the Grand Theatre in Warsaw.[36] Established in 1948, the International Press and Book Club’s chain of community centres and bookshops was part of the Prasa Workers’ Publishing Cooperative (expanded into the Prasa-Książka-Ruch Workers’ Publishing Cooperative from 1973), a press, publishing, and distribution corporation that published most Polish daily newspapers, including the daily Trybuna Ludu, the main organ of the Polish United Workers’ Party.

From that moment on, both worked as independent curators; they initiated alternative art institutions and art work collectives.

In response to the growing resentment towards Italian, Turkish and Spanish guest workers in Switzerland, Hungarian-born Szeemann founded the Agentur für geistige Gastarbeit (Spiritual Guest Worker Agency):

The agency was a one-man enterprise, a kind of institutionalisation of myself, and its slogans were both ideological – ‘Replace Property with Free Activity’ – and practical – ‘From Vision to Nail’ – which meant that I did everything from conceptualising the project to hanging the works. It was the spirit of 1968.[37]

From 1974 onwards, he exhibited series of extensive projects as part of the physically non-existent Museum of Obsessions, whose task was to give visual form to selected metaphors and themes found in culture with a positively energetic ‘obsession’ as the modus operandi of the artist and curator. Artistic efforts undertaken entirely without involvement from institutions proved rather impossible, but Szeemann tried to choose unconventional exhibition spaces. The original 1978 Monte Veritá: The Breasts of Truth, later shown in other locations, was originally situated in a picturesque resort near Ascona on Lake Maggiore in the canton of Ticino, owned by an artistic colony of followers of the various alternative movements of the early 20th century. In this eclectic architectural setting, he gave modernism and its accompanying utopian ideologies, particularly anarchism, pacifism, theosophy, Lebensreform, and Bauhaus, a new interpretation.[38] Szeemann wrote:

First you have romantic idealists, then social utopias that attract artists, then come the bankers who buy the paintings and want to live where the artists do. When the bankers call for architects the disaster starts.[39]

In 2018, on its 100th anniversary, the Kunsthalle in Bern proudly displayed a meticulous reconstruction of the low-key exhibition Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us, prepared by Szeemann in 1974 in his former flat at Gerechtigkeitsgasse 74, above the Café du Commerce in Bern (this was also the first exhibition in the new premises of Galerie Toni Gerber). It was a reconstruction of the flat that once belonged to Szeemann’s grandfather, Étienne Szeemann (1873-1971), who was a Hungarian immigrant, a soldier in the Austro-Hungarian army, a respected hairdresser, an opera wigmaker, and the inventor of the curling iron. Curiously, Étienne attended all of his grandson’s exhibitions at the Kunsthalle in Bern. After several years of renovation at the Getty Research Institute, the exhibition, including the original furniture, contained 1,200 objects.[40]

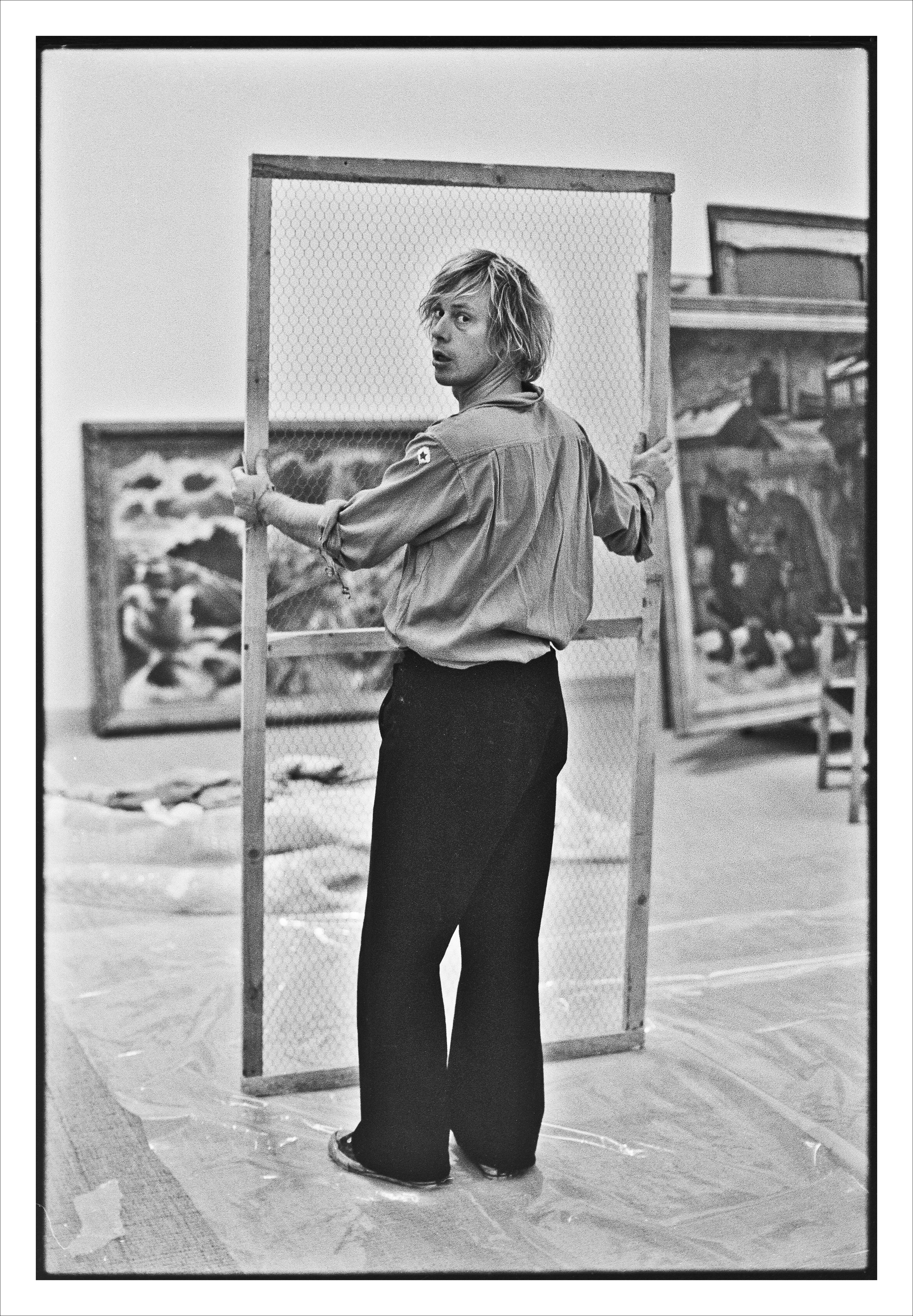

Paul Thek, Pyramid. A Work in Progress (1971), the artist at work at the exhibition, Moderna Museet, 1971, Stockholm; curator: Pontus Hultén. Photo: Erik Cornelius © Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

In 1974, Janusz Bogucki decided to pursue his activities outside state art institutions; in the late 1970s and early 1980s, he organised meetings of artists and art critics at the Retreat House in the Laski Centre for the Blind near Warsaw. They focused on the sacred in art, making him one of the initiators behind the entry of contemporary art into the Church sphere. The meetings often resembled retreats and, for many participants, were an important moment of reflection on the meaning of their own work and their outlook on life. Among the participants were eminent art historians and critics, university lecturers, many well-known avant-garde artists, as well as clergymen. The works read included those by Czesław Miłosz, Zbigniew Herbert, and Simone Weil. Bogucki thus began to realise his concept of the ‘return of art to the Home and the Temple’. His vision gradually transformed into a separate, broad current of art, with not so much artistic as political origins. Underground art magazines at the time included documents on sacred art issued after the Second Vatican Council and the writings of American neo-conservative sociologist Daniel Bell, a critic of secularisation, practising social forecasting.[41] Reference was also made to the works by the exiled Leszek Kołakowski, in particular his Odwet sacrum w kulturze świeckiej.[42]

Towards the end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, which was still a period of incredibly lively spiritual search in spontaneous discussion groups and faith communities associated with Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, Catholicism, Orthodoxy, and Protestantism, Janusz Bogucki launched the Ashram Anavim Foundation in his own home and the Ecumenical Art Monastery in the Old Boiler House in the Mokotów district in Warsaw.

I am a religious man, he explained in an interview with a young journalist in 1978, but not in any way overzealous. [...] I resent the exhilaration of the strangeness of the unexplored that is so popular today, which for many becomes a substitute for inner experience or a surrogate for religiosity. [...] The shallowness of the worldview, which is also popular among artists today, occurs where mystery devoid of depth penetrates the field of mass culture.[43]

Biography without a chronicler, art theory without a commentator

During the post-Stalin Thaw, Bogucki distanced himself from criticism as an institution and as a profession.

According to Piotr Juszkiewicz, he wandered from one artist’s studio to another in search of impressions, looking for refuge from the ‘wooden aesthetic of prescriptions’ and from the opportunism and procrastination of theory. While he chose the role of a freelancer, he distanced himself from, as he wrote, the anarchists who condemned socialist realism altogether [...], from the panic-mongers who frantically searched for trends in Western art that could be reconciled with realism, and from ‘our theoreticians’, the dispassionate scholastics of Marxism who theorised about an official turn in aesthetics.[44]

Recalling Bogucki from the time of the Thaw, Wiesław Borowski, manager of the prestigious Galeria Foksal, founded in Warsaw in 1966 and associated with a group of artists and art critics representing the Polish avant-garde (mainly graduates of the history of art at the Catholic University of Lublin), located in the former Marxist classics reading room of the Visual Arts Studio,[45] located in the annexe of the neo-Renaissance Zamoyski Palace in Foksal Street, the seat of the Association of Polish Architects and the snobbish SARP Café, said:

Mr Janusz was always a very important person for us, as he tried to popularise modern art outside of the – admittedly shaky but still valid – cultural policy in addition to giving young art historians the opportunity to make extra money. [...] Once, Mr Janusz wanted an article from Jurek [Ludwiński], so he left us in his Kraków flat and locked the door. [...] This went on for about three days, I think, and then Mrs Maria Bogucka let us out.[46]

Paul Thek, Pyramid. A Work in Progress (1971), the artist at work at the exhibition, Moderna Museet, 1971, Stockholm; curator: Pontus Hultén. Photo: Erik Cornelius © Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

In 1959, Bogucki, considered a ‘Trotskyist’, was finally dismissed from his position as editor of the Plastyka, a supplement to the national literary and social weekly Życie Literackie, published in Kraków between 1951 and 1990. The reason for this was the exhibition he organised in 1957 for the international Phases movement, representing the second, post-war wave of Surrealism, at the oldest Polish gallery founded by the Grupa Krakowska Art Association in the Gothic cellars of the Krzysztofory Palace on the Kraków’s Main Square. On display in a showcase was a leaflet signed by poet André Breton (1896-1966; author of 3 Surrealist manifestos) and Mexican communist muralist Diego Rivera, containing the manifesto Pour un art révolutionnaire indépendant (For an Independent Revolutionary Art) which was written jointly in July 1938 in Mexico by Breton and the Bolshevik Lev Trotsky (1879-1940; proponent of the theory of permanent revolution). Young French artist Jean-Jacques Lebel (son of Robert Lebel, art critic and close friend of Marcel Duchamp)[47] presented Breton’s message to Polish intellectuals, delivered on 4 June 1959 (later printed in excerpts in the Plastyka), from a tape recording. However, the anti-government message was distorted due to an incorrect translation, which irritated the doyen of Surrealism. Breton was informed of the mistranslation in Bogucki’s press account of the exhibition opening by the émigré writer Konstanty Jeleński (1922-1987), associated with the Parisian magazine Kultura, who believed that there had been some political interference.[48] In his letter to J. J. Lebel, dated 1 October 1959, Bogucki explains that the mistranslation was accidental and it was only Professor Artur Sandauer (a classical philologist) who knew how to recognise the correct sense of the statement. The Plastyka was suspended.[49]

This is how Borowski recounted a situation that took place in 1959-61, when Jerzy Ludwiński was editor-in-chief of the Struktury, a supplement to the Lublin-based socio-cultural biweekly Kamena:

I remember when we met Janusz Bogucki at Nowy Świat Street and Jurek suggested that he should write something for the Struktury. Mr Janusz replied, ‘But what would I write about?’ ‘About anything you want, Mr Janusz.’ ‘And when would it be due, Mr Jurek?’ ‘That is up to you, Mr Janusz.’ Of course, he finally received the article. In the 1960s, Bogucki, associated with the Central Counselling Centre for the Amateur Artistic Movement, started a popularisation campaign [...] in the form of art lectures; that is, a ‘lecture’ was better paid and a ‘talk’ less so. They were given by Urszula [Czartoryska], Jurek [Ludwiński], and other art historians. [...] Bogucki was an important figure for me until the very end. He was a man of enormous culture, a great writer, but he didn’t really fit in with our radicalism.[50]

In autumn 1980, Raport o stanie krytyki (Report on the State of Criticism) was commissioned as part of Raport o stanie kultury (Report on the State of Culture), prepared by the Conciliation Committee of Creative and Scientific Associations (chaired by Klemens Szaniawski, professor of logic at the University of Warsaw, Warsaw insurgent, son of Władysław of the Junosza coat of arms).

Andrzej Turowski and I used to go to Bogucki, who commissioned us to prepare a study of art criticism in communist Poland. We toured all the magazines with revolutionary passion, giving gentler treatment only to the Projekt. We walked around like some kind of judges or commissioners of the cultural revolution, recalls Borowski, who was also an actor in Tadeusz Kantor’s Cricot 2 Theatre.[51]

In the report, Borowski, Bogucki, and Turowski wrote the following:

At every level, the propagation and dissemination of art has ceased to be a sphere of art itself and, having become part of the administrative apparatus of dissemination, passed into the domain of political propaganda, [...] while the critical emptiness [of press criticism] and its apparent dynamism created the surface of the vacuum. A vacuum filled with cultural policy.[52]

The authors proposed the organisation of a Centre for Contemporary Art, an interdisciplinary animator of current artistic life.

Janusz Bogucki was a representative of the Polish pre-war intelligentsia with a traditional ethos of social service, combining Catholicism with a community-minded attitude. After the war, he collaborated with the next generation of Polish intelligentsia, whose obligatory reading was a collection of historical and political essays by philosopher, intellectual historian, and opposition activist Bohdan Cywiński, published in 1971 in the then formative book Rodowody niepokornych, which created a platform for a confrontation between open-minded Catholicism and the continuators of the secular ethical tradition – especially during the meetings of the Culture Section at the Club of Catholic Intelligentsia in Kopernika Street in Warsaw.[53] The popular self-education circles, the Flying University, and the Society of Scientific Courses operating during the tsarist era from the 1880s onwards (aimed especially at women, for whom the path to education, not only abroad, was rather inaccessible), analysed comprehensively in the essays, returned under identical names after almost one hundred years in the opposition circles at the end of the People’s Republic of Poland.

Janusz Bogucki’s complex artistic biography still awaits its chronicler and commentator.

Paul Thek, Pyramid. A Work in Progress (1971), the artist at work at the exhibition, Moderna Museet, 1971, Stockholm; curator: Pontus Hultén. Photo: Erik Cornelius © Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

Pop, Ezo, Sacrum against the waste paper of conceptualism

With the declining attractiveness of the avant-garde tradition, together with its rush for novelty and its exaltation of European progress and revolution, linked to a secular and homocentric model of culture, in a situation described as the ‘end of art’, Bogucki predicted that at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, three tendencies, being an expression of the artists’ worldviews, would clash in art: Pop, Ezo, and Sacrum. He presented his considerations in papers that were first created as lectures, given on numerous occasions at meetings and open-air workshops for artists, theoreticians and art enthusiasts, later published in various periodicals between 1976 and 1986, and written with the idea that they would become a book.[54]

The POP movement is a pragmatic visual production born out of conceptualism, based on mass culture operating in a technological consumerist Euro-American civilisation of competition and success, founded on an alliance of totalitarian and managerial mechanisms. Artists are perpetually available operators of the social imagination, experts, and managers. Artistic criticism has been replaced by an ‘expert assessment of the utility and level of execution of the work’.[55] Nothing is sacred – either in a religious or artistic sense. What remains is high-quality, service-oriented visual engineering. Both the sacred and the sacred of art are ignored. One example of the Polish Pop trend that has been identified is Warsaw’s student-run Galeria Remont and the Marxist milieu of young Wrocław residents associated with the Galeria Sztuki Najnowszej and the Grupa Sztuka i Teoria.

The EZO movement is a kind of esoteric intellectualism in art, building on the autonomy, freedom, hermeticism, and isolation of art, a counter-trend to Pop, also rooted in conceptualism. Esoteric artists:

do not seek wider publicity, guard the purity of the spiritual perch on which they engage in their practices of thought and imagination, [...] tend to nurture their connections with related circles in other countries, [...] are themselves commentators, [...] tend to write in an enigmatic, half-poetic, half-scientific language.[56]

Sensitive egocentrics interested in cultivating their own uniqueness, shunning the non-artistic concerns of this world, are united by a belief in the exclusive sacredness of art and its unlimited freedom and independence; there is only the sacred aspect of art. The cited examples of the Polish Ezo trend include Poznań’s Galeria Akumulatory and Warsaw’s Galeria Foksal.

The SACRUM movement is an effort to resacralise culture in the ‘Civilisation of Haste and Success’, to renew the link between the sacredness of art and the sacred in its original sense, as it was understood by the religious scholar Mircea Eliade, who in his anthropological concept of homo religiosus (religious man) considered religiosity to be the eternal distinguishing feature of the essence of humanity. A higher ethical awareness is the foundation for the coexistence of people with people and civilisations with nature within the framework of a global culture that is forming, while preserving the diversity of communities and individuals [Bogucki used the term ‘globe society’, ‘globe culture’]. It is a movement to renew the inner bond between the experience of creativity and faith, between art and religion, the connection between creativity and the entire spiritual life that has matured over the millennia, the gravitation towards areas of inner life, linked to the need for unhurried and timeless reflection. The period of the Chaos is followed by a return to the Home and the Temple. In the return of the sacred, the sacred and the sacred of art are brought closer together.

The envisaged major art movement is conceptualism, which, by combining a propensity for scientific reasoning with multi-directional training of the imagination, becomes the backbone of conceptual work in the two opposing movements of Pop and Ezo. For the thousands and thousands of young people of different nationalities, the method of conceptual ‘notation’ opens up the opportunity to quickly enter the global new art market. However, due to the immense ease and abundance of this post-conceptual production, ‘it rarely turns out to be art rather than waste paper, and is far more often clichéd rather than imaginative’.[57]

Bogucki draws a vision of a world in which young exploiters of conceptualism will have the duty to informatively shape and label space in order to ensure the optimisation of labour productivity and the contact of the masses with administrative structures. By perfecting the multifunctional supericonosphere, they will create a space of permanent fascination combined with the tasks of creating relaxation illusions, such as:

[...] visually directing shows that serve to pile up and discharge the emotions of the crowd, showing the controlled hideaways of lyrical contemplation to the yearning, the opportunities to savour asceticism to the satiated, [...] and to everyone – the allure and inevitability of the prospects chosen for them to see.[58]

Visual artist productions inspired by sociology, social psychology, anthropology, mass culture, advertising, and television:

reveal themselves, their moods, reflections, temperaments, insights, and especially their need to be displayed in public, [...] they show how their authors play football and smoke cigars, how the authors cross the road and disappear into the crowd, consume food products, drive a car, interact with the environment or make faces at the camera.[59]

The practitioners of self-reflection of the conceptual ‘aesthetic template’ from the Ezo movement also have a distinguished fondness for expert reading, especially in philosophy, linguistics, anthropology, astronomy, and logic. The encrypted hermetic activities are underpinned not only by imagination but also by erudition and intellectual discipline. The scientific approach goes hand in hand with magical behaviour, through which those gathered are reassured that the increasingly elusive presence of art will become more real thanks to the ‘strenuous hope of a group of séance participants’. With his usual insight and good-natured irony, Bogucki describes the development of this formation in Poland in the following manner:

Those who did not have the patience to read the books until they understood them nevertheless achieved a certain degree of proficiency in the scientific vocabulary. Poland, a country of masters and professors of fine arts, has a considerable track record in this regard – almost like our nobility, who spoke Latin in the age of Sarmatism.[60]

On the other hand, a frequently cited positive example of artistic conceptual practice that comes close to the Sacrum approach is the work of American sculptor Paul Thek (1933-1988) – Pyramid. A Work in Progress (1971), an elaborate spatial installation created from simple natural elements of rural life and landscape. Susan Sontag’s 1966 classic collection of essays on art criticism, Against Interpretation, dedicated to Thek, owes its title to conversations with the artist.[61] In the 1960s, inspired by the Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo, Sicily, filled with 8,000 mummies of clergy and laity in festive dress, Thek became famous, in the context of the Vietnam War in particular, for his series of works Technological Reliquaries. These included naturalistic wax sculptures, depicting pieces of meat (some of which were covered in flies) or casts of human limbs covered in fragments of classical Roman armour stored in acrylic glass showcases.

Thek’s ephemeral spatial installation Ark. Pyramid was presented before Documenta 5 by Edy de Wilde as the 1969 The Procession. The Artist’s Coop in Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, and then by Pontus Hultén in 1971 as Pyramid. A Work in Progress in Moderna Museet in Sztokholm. The work, initially titled A Procession in Honor of Aesthetic Progress: Objects to Theoretically Wear, Carry, Pull, or Wave, was compiled for the first time in 1968 for an exhibition at Galerie M.E. Thelen in Essen. Fascinated by the processions of the Catholic liturgy, Thek wrote to his friend, literary scholar Ed Burns: ‘I want to do a crazy show, a procession, and do all the things that people carry and wear in a procession, like jewellery and masks and shrines etc. and it could be a joy to do.’[62] He prepared simple sculptural objects such as chairs to be carried on the shoulders, glazed wooden showcases as headgear, a lectern, flying birds. Red represented hell, pink the ‘here and now’, white referred to the sky. During transport to the German gallery from Rome, where the artist was living at the time, the works were severely damaged. Thek decided to fix them during the show, completing the work a week before the closing date, giving the exhibition a different look every day. He added the subtitle ‘A Work in Progress’ to explain to critics that this was his intention from the start. And so, this vast ambient environment, prepared in collaboration with a rotating group of artists called The Artist’s Coop (which included photographer Peter Hujar and associates of theatre director Robert Wilson[63]), was later shown in station after station. In the Kunstmuseum in Lucerne in 1973, with another installation Ark, Pyramid, Easter – A Visiting Group Show, Thek officially abandoned the idea of individual authorship in favour of a collaborative method. The show at the Lehmbruck Museum in Duisburg in the winter of 1973/1974, titled Ark, Pyramid – Christmas (The Manger), was accompanied by a nativity play written by the artist and performed by local children.

Paul Thek, In Process (Stockholm), archival exhibition, the Pontus Hultén Study Gallery, Moderna Museet, 2013, Stockholm; curators: Susanne Neubauer and Annika Gunnarsson. Photo: Åsa Lundén © Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

In 2013, the Moderna Musset in Stockholm prepared presentation Paul Thek. In Process (Stockholm) in the Pontus Hultén Study Gallery, designed by Italian architect Renzo Piano, which was an attempt to reconstruct the memorable Pyramid. A Work in Progress from 1971. It consisted of letters, photographic documentation, and a book.[64]

The understanding of the Sacrum movement is close to Eliade’s concept of ‘archaic ontology’, described by Wiesław Juszczak as seeing all manifestations of nature and life as ‘explicit or indirect, reflexive as it were, signs of hierophany, [...] in which [Gombrich’s] ‘sense of order’ is coupled with a ‘sense of mystery’.[65] Referring to Paul Ricoeur, Gabriel Marcel, and Martin Heidegger, Juszczak distances himself from the megalomania of subjectivity in the conviction that in art, just like in philosophy, there is no ‘progress’ and therefore no ‘backwardness’ either.[66]

Bogucki explains that the works created as part of the sacred approach:

are seemingly impersonal creations, whose essence is to emanate hidden meanings rather than to present the author’s personality, experiences, temperament, or a new aesthetic concept. He emphasises the contrast between this type of artwork, between its ‘silence’ and the hustle and bustle of a large-scale funfair-like exhibition. So perhaps it is not the exhibition, not the gallery, not the participation in the art facts exchange that is their proper situation and purpose.[67]

As he wrote these words, he vividly remembered the great exhibition of the St Mary’s Altar decomposed into dozens of figures and other elements and set up at the Wawel Castle after the post-war restoration of the work had been completed.

Paul Thek, In Process (Stockholm), archival exhibition, the Pontus Hultén Study Gallery, Moderna Museet, 2013, Stockholm; curators: Susanne Neubauer and Annika Gunnarsson. Photo: Åsa Lundén © Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

Time has confirmed the Polish theorist’s diagnosis; Peter Osborne, contemporary British art philosopher, in his most recent publications puts forward and extensively justifies the thesis that contemporary art is post-conceptual art. It is an element of production, circulation, exchange, consumption, and conservation within the institutions of art in the global network of capitalist societies, comprehensibly and critically unifying the twentieth-century field of art.[68]

At the same time, within the currently observed social turn in art, which is geared towards shaping social consciousness and whose theoretical points of reference – as argued by British art historian Claire Bishop – are in particular Walter Benjamin, the Situationist International, and Gilles Deleuze, contemporary activist art practices mainly include socially engaged art, critical art, and participatory art. What counts is effective social impact; the activist or agitator artist constructs strategies and enters the role of the director of the situation in order to provoke social change with the intention of spreading civic culture and overcoming social exclusions. Art is all about pragmatism and utilitarianism and the striving to engage the viewer, often also in public spaces.[69] A good example of current community art practices is the collective cultivation of vegetable gardens to promote urban gardening in local communities.[70]

Paul Thek, In Process (Stockholm), archival exhibition, the Pontus Hultén Study Gallery, Moderna Museet, 2013, Stockholm; curators: Susanne Neubauer and Annika Gunnarsson. Photo: Åsa Lundén © Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

The impoverished artistic arrangement and the decay of the avant-garde

The forecast for the development of art, formulated more than 40 years ago, at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, is presented by Bogucki ‘from the position of a long-term participant in events, guided in his conviction above all by observational realism’.[71] Based on a diagnosis of the then existing state of affairs, he introduces an operational concept – the ‘artistic arrangement’. This is discussed most extensively in his 1977 Dewaluacja współczesnego układu artystycznego.[72]

The contemporary artistic arrangement is ‘a system of concepts, ideas, customs, and institutions conditioning the way artists act and art manifests itself in social life’,[73] which emerged in modern European culture and developed during the modern period. The main principle of the artistic arrangement is that the author produces objects (including designs, situations, or ideas). In the public’s view, these objects are important for the following reasons: they are creations (traces) of the author’s personality; they are objects of art, considered to be a special and separate sphere of life; they exist as objects of commerce, collecting, display, critical commentary, scientific research, publishing and popularisation endeavours; they are signs of artistic evolution, novelty, and the avant-garde.[74]

The contemporary artistic arrangement is historically limited. In most pre-modern cultures, neither the personality or special qualities of the artist nor the criterion of the object’s belonging to the scope of the autonomous realm of art were important for the evaluation of the work, although the quality of artistic execution was appreciated. The works of art were usually associated with a place of worship or the seat of the ruler, but apart from ornamental and utilitarian products they were not traded, collected, or exhibited. In ancient sacred cultures with an unchanging model of the human world, tradition and collective wisdom were important, in contrast to the contemporary system of the exploitation of authors and the management of original objects, based on the principle of individual creation and the idea of original art, of the creative individual producing new visual propositions and objects useful for commerce and collecting.

The avant-garde model of the artistic arrangement, being both a certain idea and a system of institutions, together with its inherent cult of novelty and celebrity competitor authors and the associated system of institutions for the breeding and exploitation of artistically gifted individuals will gradually calcify and disintegrate, although it will long continue to serve as relics of a bygone era, [...] has confined art to channels and showrooms reserved for it, detaching it from its natural connection with the whole human spiritual development.[75] [...] Anyone who has been visiting exhibitions of contemporary art of the last two decades on a more or less regular basis will remember these successive waves of inspiration brought to the authors of paintings, sculptures, prints, textiles, posters, and illustrations by Tashisme, pop art, New Figuration, etc., all the way up to conceptualism and hyperrealism. Then, and it was the early 1970s, the supply was cut off, so to speak.[76]

However, the avant-garde artistic arrangement will not collapse immediately, ‘for several decades it will be able to rework the traditional original products of eclectics, academics, originals, stragglers of the former avant-garde, etc.’ during the review of the eclectic processing of the news of yesterday and the day before yesterday.[77]

According to Bogucki, the new avant-garde art of the 19th and 20th centuries successfully carried out its historical task in the name of the freedom of the human person with two unprecedented operations: the gradual devaluation, unmasking, disassembly and destruction of images serving deep interpersonal communication, present in the mythologies and cults of past eras, and the revolutionary liberation of the abstract language of form from traditional conventions. From that point on, art was to be used to compose free personal visual messages – spiritual messages addressed to a faceless exhibition audience.

But the convergence of this pure language with the organisation of space, production, and information has contributed more to the dependence of societies’ imaginations on the illusory stars and fashions of mass culture rather than to the expansion of man’s inner freedom and his capacity for independent judgement and choice. [...] The liberated language of form was also meant to serve human freedom as a factor in the great reconstruction of the social positioning of the individual: the organisation of the human environment in the name of the demythologisation, rationalisation, and democratisation of collective life was in fact facilitated by such individual messages.[78]

Bogucki noted that one could observe a decay of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century avant-garde as a phenomenon that has fulfilled its historical function and has no further reason to exist, and the gradual disappearance of this modern European model of culture with its isolated asylum for art and artists, with its cult of individual celebrity, the work of art as a document of the individual psyche, as an exhibit, an object to be traded and collected.[79]

Artistic arrangement: artworld and artistic field

The concept of the ‘artistic arrangment’ introduced by Bogucki is at the intersection of two notions operating in contemporary art theory: the artworld and the artistic field.

The concept of the artworld was introduced in 1964 by American postanalytic philosopher and art critic Arthur C. Danto (1924-2013), a researcher studying the work of Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp’s introduction of ready-mades, objects that gain aesthetic significance through the very act of display – such as Bottle Rack (1914) or Fountain (1917) – resulted in an expansion of the set of objects considered artistic and a strengthening of the role of the creator artist. The idea became the artistic subject and novelty was given priority. The work of art needed a commentary, and art gradually transformed into a philosophical commentary on art. Danto distinguished three stages in the development of art: imitative art (which ended with the advent of film), realist art (the neo-avant-garde of the second half of the 20th century), and cognitive art, which is self-reflective and signals the ‘end of art’ and begins the post-historical period. The Socratic essentialist question ‘what is art?’ assumes a new form: ‘why is something a work of art’ The idea of the artworld was initiated by Warhol’s 1964 exhibition at the Stable Gallery in New York, where he displayed his Brillo Box, consisting of plywood imitations of cardboard cleaning product packaging stacked in neat piles from floor to ceiling as though in a supermarket.

Is that man some kind of Midas who transforms everything he touches into pure gold of art? And is the whole world composed of concealed works of art waiting, like the bread and wine of reality, to be transformed by some dark mystery into the indistinguishable flesh and blood of a sacrament?[80]

He gave the term ‘art world’ that has already been functioning in informal language the meaning of an aesthetic category. An everyday object becomes a work of art when it is interpreted. The philosophical interpretation constitutes the artwork, and therefore knowledge of art theory and history and cultural conventions is required.

In order to see something as art, one needs an element that cannot be detected by the eye – the atmosphere of artistic theory, the knowledge of art history; the artworld. [...] The artworld has as much to do with the real world as the state of God has to do with the earthly state. Certain objects, just like certain individuals, enjoy dual citizenship. [...] The more a person knows about the entire population of the artworld, the richer their experience with any of its components. [...] Sometimes fashion favours certain rows of the contact matrix: museums, connoisseurs, and other style elements are the counterbalance in the artworld.[81]

As a result of the theoretical turn in art started by the avant-garde, theory became an integral component of the artworld.

Danto contributed to the emergence of a new conventionalist and institutional definition of art. It is the artworld, the network of communities and institutions (such as art schools, museums, galleries, or academies) involved in the creation of art theory with reference to historical contexts, that decide what constitutes art. The institutional definition was most fully developed by George Dickie, who identified five necessary elements of the artworld: an artist who produces the artwork, an artwork as an artefact created for presentation to an artworld public, an audience prepared to understand the object presented, an artworld as the sum of all artworld systems, an artworld system as a framework for the artist’s presentation of the artwork to an artworld public.[82]

The term ‘artistic fields’ was introduced by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1930-2002), founder of the theory of symbolic violence. The artistic field is part of the field of cultural production, highly influenced by the social class of anarchist intellectuals; it is characterised by liberal moral norms and the rejection of the illusion of economic success. The author, referring to Danto, writes as follows:

The experience of the work of art as directly gifted with meaning and value is created by the harmony between the two aspects of the same historical institution, the nurtured habitus [an individual’s competences and permanent cultural dispositions] and the artistic field, which mutually condition each other. [...] It is the eye of the aesthete which constitutes the work of art. [...] Museums could display a sign above the entrance: ‘Let no one who is not an art lover come here’.[83]

The modern artist, along with the magic of their signature, is the product of the artistic field, which is an autonomous social universe. It includes institutions that determine the functioning of cultural goods, such as exhibition venues (galleries, museums), instances of consecration (academies, salons), institutions that reproduce artists (art schools), specialised subjects (art dealers, critics, art historians, collectors) that decide on the artist’s evaluation and the value of a work of art. Citing Walter Benjamin, he argues that work-of-art-as-fetish has been replaced by the ‘fetish of the name of the master’.[84]

Summing up, the conventionalist and institutional definition of art described above has always been an essential and constitutive point of reference ‘in the formative processes of the modern salon and dealer-critic artistic systems and of the place and role of criticism in the artistic arrangement’.[85]

Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume (1711-1776) can be considered the father of the theoretical approaches described above within the consensual definition of art.

‘Though the principles of taste be universal, and, nearly, if not entirely the same in all men,’ writes Hume in Of the Standard of Taste, ‘yet few are qualified to give judgement on any work of art, or establish their own sentiment as the standard of beauty.’ [...] Poets’ works, more lasting than bronze, would crumble like common brick or clay if the constant revolutions in customs and lifestyles were disregarded and only those things that conformed to the prevailing fashion were recognised in art. Should we throw away the portraits of our ancestors because they are depicted in ruffs and crinolines?[86]

Hume, the master of the essay, thought that people who engage in the operation of the mind may be divided into the learned and conversible. The former are inclined to seek solitude for their studies, the latter seek companionship to exchange thoughts, observations, and news. He watched with satisfaction as the alliance between the world of science and the world of conversation deepened before his eyes. ‘I cannot but consider myself as a kind of resident or ambassador from the dominions of learning to those of conversation.’[87] According to Hume, aesthetic valuation originates from a certain agreement and has a certain institutional basis; beauty is not an attribute of the object but rather a state of mind: aesthetic judgement is therefore a generalisation, an observation of what was commonly liked. The basic criterion of beauty is the approval of critics, a certain cultural elite, with good taste and extensive education, whose judgement will be confirmed by time. The consensus, a certain social agreement, is the decisive instance for the court of taste that captures the elusive, irrational and unspeakable Leibnitzian je ne sais quoi.

Even in the most cultured eras, a fair critic of art is rarely found. Such a title can be claimed by a profound mind combining subtlety of opinion, supported by experience, refined by comparison and free from all prejudice; only the concordant judgement of such critics, wherever they are, is the real test of taste and beauty.[88]

[1] Department of Visual Education and Art Research, Faculty of Fine Arts, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, bio ‘Janusz Bogucki’, https://www.zea.umk.pl/janusz-bogucki/ [11/05/22]. In 2005, the Program Council of art education in visual arts at the Nicolaus Copernicus University established the Janusz Bogucki Medal, awarded annually to the most outstanding graduate of the faculty.

[2] P. Majewski, Bogucki Janusz, in: Słownik polskiej krytyki artystycznej XX i XXI wieku. Volume I., (ed.) R. Kasperowicz, M. Lachowski, P. Majewski, TN KUL, Lublin 2020, p. 21.

[3] Online publication Odrzucone dziedzictwo. O sztuce polskiej lat 80., Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej, Warsaw 2011 begins with Dorota Jarecka’s Janusz Bogucki, polski Szeemann?.

[4] During the 100-day event, Joseph Beuys came every day to his Bureau for Direct Democracy.

[5] Germano Celant, Arte Povera: Notes for a Guerilla War, “Flash Art”, Issue 5, 1967. It is sometimes believed that the idea of arte povera was inspired by Jerzy Grotowski’s idea of a ‘poor theater’. Cf. J. Grotowski, Towards a Poor Theatre, preface by Peter Brook, Holstebro, Odin Teatrets Forlag, 1968; Polish ed.: Ku teatrowi ubogiemu, translated by G. Ziółkowski, ed. L. Kolankiewicz, Instytut im. Jerzego Grotowskiego, Wrocław 2007.

[6] When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969 / Venice 2013, 01/06-03/11/13, Fondazione Prada, Venice, [21/05/22] See more: Germano Celant, A readymade: When Attitude Become Form, in: When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969 / Venice 2013, exhibition catalogue, Progetto Prada Arte, Milan 2013.

[7] Harald Szeemann Archive and Library, [11/05/22]; Mike Boehm, Getty gets NEH grant to organize huge contemporary art archive, 22/03/2012 [11/05/22].

[8] Nie ocenzurowano. Polska sztuka niezależna lat 80., 8/04-18/08/2022, CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, Warsaw, [21/05/2022].

[9] J. Bogucki, Od rozmów ekumenicznych do Labiryntu, CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, Warsaw 1991, p. 51.

[10] Ibid., p.107.

[11] Ibid., pp. 54, 55, 62.

[12] More about Janusz Bogucki’s collection: Piotr Kopszak, Zapomniana kolekcja, “Obieg.pl”, 11/07/2021, [21/05/2022].

[13] H.U. Obrist, Krótka historia kuratorstwa, translated by Martyna Nowicka, Korporacja Ha!art, Kraków 2016, p. 105.

[14] J. Bogucki, Od rozmów..., op. cit., p. 9.

[15] H.U. Obrist, op. cit., p. 84.

[16] Ibid., pp. 86-87.

[17] Ibid., pp. 92, 106.

[18] The film Azyl dla większości, directed by Olaf Olszewski, Video Studio Gdańsk, 1989, 34 min 35 sec. Video recording of selected independent cultural events from the Congress of Polish Culture (12-13/12/1981) to the Independent Culture Forum (1/04/1989).

[19] J. Bogucki, Od rozmów..., op. cit., p. 7.

[20] A. Searle, Through the square windows, “TheGuardian.com”, 15/11/2006, [23/05/22].

[21] H.U. Obrist, op. cit., p. 95.

[22] J. Bogucki, Od rozmów..., op. cit., pp. 13, 17-18.

[23] H.U. Obrist, op. cit., p. 92.

[24] J. Bogucki, Pop-Ezo-Sacrum i sprawa polska (1979), in: J. Bogucki, Pop - Ezo - Sacrum, Pallotinum, Poznań 1990, pp. 57-58.

[25] V. Flusser, Gest i uczuciowość, in: V. Flusser, Kultura pisma. Z filozofii słowa i obrazu, translated by P. Wiatr, Warsaw 2018, p. 100.

[26] Ibid., pp. 112-113.

[27] P. Wiatr, Filozofia kultury „po Bogu” – o powrocie do człowieka i transcendencje raz jeszcze, in: V. Flusser, Kultura pisma, op. cit., p. 387.

[28] E. Cassirer, Esej o człowieku. Wstęp do filozofii kultury, translated by A. Staniewska, Warsaw 2017, p. 48.

[29] Cf. Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus logico-philosophicus, translated by B. Wolniewicz, Warsaw 2000, p. 64.

[30] P. Wiatr, op. cit., p. 394.

[31] V. Flusser, Gest tworzenia, in: V. Flusser, Kultura pisma, op. cit., pp. 14-15.

[32] The intricate relationship between scientists, artists and politicians is discussed by Flusser in his essay Art and Politics written for the American art trade magazine Artforum, in: V. Flusser, Kultura pisma, op. cit., pp. 124-132.

[33] V. Flusser, O ważności sztuki dla przetrwania, in: V. Flusser, Kultura pisma, op. cit., p. 141.

[34] Ibid., pp. 145-146.

[35] Ibid., pp. 40-41.

[36] D. Jarecka, op. cit., p. 26.

[37] H.U. Obrist, op. cit., p. 93.

[38] Information about the Monte Veritá project at the Getty Institute’s website.

[39] H.U. Obrist, op. cit., p. 98.

[40] Exhibition Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us was part of the touring exhibition Harald Szeemann – Museum of Obsessions (2018), curators: Glenn Phillips & Philipp Kaiser, Getty Research Institute.

[41] A. Gralińska-Toborek, Plastyka w Kościele w latach 1981-1989: trwałe przymierze czy epizod?, “Pamięć i Sprawiedliwość”, Issue 4/1 (7), 2005, pp. 187-188.

[42] L. Kołakowski, Odwet sacrum w kulturze świeckiej, “Nawa św. Krzysztofa”, Issue 2, 1985. Later published legally in: L. Kołakowski, Cywilizacja na ławie oskarżonych, Warsaw 1990.

[43] J. Bogucki, Pop-Ezo-Sacrum..., in: J. Bogucki, Pop..., op. cit., p. 58.

[44] P. Juszkiewicz, Od rozkoszy historiozofii do „gry w nic”. Polska krytyka artystyczna czasu odwilży, WN UAM, Poznań 2005, p. 110.

[45] On the origins of the Galeria Foksal’s success: Agnieszka Sural, Wiesław Borowski: Wystarczy wierzyć dobrym artystom [wywiad], “Culture.pl” of 16/04/2015, [15/05/2022].

[46] W. Borowski, Zakrywam to, co niewidoczne. Wywiad-rzeka Adama Mazura i Ewy Toniak, Stowarzyszenie 40 000 Malarzy, Warsaw 2010, pp. 71, 87.

[47] Through the efforts of J. J. Lebel, a facsimile of Duchamp’s historic 1959 catalogue raisonné, created in close collaboration between the artist and his father, was published after more than 60 years: Robert Lebel, Marcel Duchamp, with texts by Marcel Duchamp, André Breton, H.P. Roché, translation by G.H. Hamilton, Hauser & Wirth Publishers, Zurich 2021. The publication is accompanied by a supplement edited by J. J. Lebel & Association Marcel Duchamp with a selection of new texts.

[48] Wernisaż wystawy Phases i message André Bretona, “Życie Literackie”, supplement “Plastyka” No 34, 1959, Issue 392, p. 5.

[49] D. Jarecka, op. cit., pp. 25-26. The author discusses this more extensively in her book Surrealizm, realizm, marksizm. Sztuka i lewica komunistyczna w Polsce w latach 1944-1948, Instytut Badań Literackich PAN, Warsaw 2021, pp. 17-19, 64-65; About the Phases: G. Dziamski, Powojenna faza surrealizmu, “Sztuka i Filozofia”, Issue 10, 1995, pp. 183-187.

[50] W. Borowski, op. cit., pp. 98-99, 179.

[51] W. Borowski, op. cit., pp. 86, 546-547.

[52] W. Borowski, J. Bogucki, A. Turowski, Sztuka i krytyka, “Odra”, Issue 1 (January), 1981, (pp. 37-44), pp. 41-42.

[53] B. Cywiński, Rodowody niepokornych, Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak, “Biblioteka Więzi” series, Kraków 1971. Forty years after the publication of the nonconformist’s must-read of the 1970s and 1980s, it was mentioned in the debate that at a charity ball held by the Club of Catholic Intelligentsia in connection with an auction of a book signed by the author, his son, medievalist Piotr Cywiński, PhD said, ‘My advice to my Dad would be that since he wrote Rodowody niepokornych (The Origin of the Rebellious) back then, he should now write Korowody niepozornych) (The Processions of the Inconspicuous); in: Gawin, Sutowski, Zając: Debata o „Rodowodach niepokornych” w Stoczni, “Kultura Liberalna”, Issue 107 (4/2011) of 25/01/2011, [21/02/2022].

[54] J. Bogucki, Pop-Ezo-Sacrum, Pallotinum, Poznań 1990. He discusses these 3 contemporary art trends more extensively in his essay Trzy magnetyzmy, czyli mały traktat prognostyczny (1978), pp. 27-45.

[55] J. Bogucki, Pop-Ezo-Sacrum i sprawa polska (1979), in: J. Bogucki, Pop..., op. cit., p. 67.

[56] Ibid., pp. 67-68. Bogucki suggests that with authors from the Ezo trend, the distinction between the role of artist and theorist is blurred: ‘Critic and theorist Jerzy Ludwiński formulates his statements along the lines of philosophical essays, prose poems, visions and drawing and conceptual diagrams, suitable for display beside strictly artistic works’; ibid., p. 68.

[57] J. Bogucki, O możliwościach wyjścia i pozostania (1976), in: J. Bogucki, Pop…, op. cit., p. 13.

[58] J. Bogucki, Trzy magnetyzmy, czyli mały traktat prognostyczny (1978), in:, J. Bogucki, Pop..., op. cit., pp. 34-35.

[59] J. Bogucki, Od rozmów..., op. cit., p. 18.

[60] Ibid., p. 18.

[61] S. Sontag, Przeciw interpretacji i inne eseje, translated by A. Skucińska, D. Żukowski, M. Pasicka, Wydawnictwo Karakter, Kraków 2012. Sontag also dedicated her 1989 book on the phenomenon of illness to Paul Thek: S. Sontag, Choroba jako metafora. AIDS i jego metafory, translated by J. Anders, Wydawnictwo Karakter, Kraków 2016.

[62] Paul Thek, A Procession in Honor of Aesthetic Progress: Objects to Theoretically Wear, Carry, Pull, or Wave, 1968, transcript of an audio recording, Whitney Museum of American Art, [9/06/2022]

[63] In an exhibition currently on show at the New York Design Gallery, avant-garde director Robert Wilson presents numerous small glass figurines of a pyramid, a stag and a doe as a tribute to Paul Thek, his friend and collaborator. Exhibition by Robert Wilson, A Boy from Texas, Cristina Grajales Gallery, New York, 6/05-9/09/2022, [15/06/2022].

[64] Exhibition Paul Thek. In Process (Stockholm), Moderna Museet, Stockholm, curators: Susanne Neubauer, Annika Gunnarsson, 23/03-15/09/2013, [9/06/22]. Accompanying publication: S. Neubauer, Paul Thek in Process, JRP Ringier, Zurich, 2012.

[65] W. Juszczak, Fragmenty. Szkice z teorii i filozofii sztuki, Royal Castle in Warsaw, Warsaw 1995, p.167.

[66] W. Juszczak, Pani na żurawiach. Część pierwsza: Realność bogów, Aureus, Kraków 2002, pp. 14-15.

[67] J. Bogucki, Dewaluacja współczesnego układu artystycznego (1977), in: Pop-Ezo-Sacrum, op. cit., p. 25.

[68] P. Osborne, Anywhere or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art, Verso Books, London-New York, 2013; P. Osborne, The Postconceptual Condition, Verso Books, London-New York, 2018.

[69] C. Bishop, Sztuczne piekła. Sztuka partycypacyjna i polityka widowni, translated by J. Staniszewski, Fundacja Nowej Kultury Bęc Zmiana, Warsaw 2015, pp. 20, 33.

[70] E. Jabłońska, Nieużytki sztuki, Galeria BWA Zielona Góra, Zielona Góra 2014.

[71] J. Bogucki, Trzy magnetyzmy, czyli mały traktat prognostyczny, op. cit., p. 29

[72] J. Bogucki, Dewaluacja współczesnego układu artystycznego, in: J. Bogucki, Pop..., op. cit.., pp. 17-25.

[73] Ibid., p. 19.

[74] Ibid., p. 19.

[75] J. Bogucki, Od rozmów..., op. cit., pp. 8, 9.

[76] J. Bogucki, Pop..., op. cit., p. 21.

[77] Ibid., p. 238.

[78] Ibid., p. 11.

[79] Ibid., p. 13.

[80] A. C. Danto, Świat sztuki, in: A. C. Danto, Świat sztuki. Pisma z filozofii sztuki, translation, editing and introduction by L. Sosnowski, Wydawnictwo UJ, Kraków 2006, p. 43.

[81] Ibid., pp. 42, 44, 46.

[82] The Definition of Art, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, [29/05/22].

[83] P. Bourdieu, Reguły sztuki. Geneza i struktura pola literackiego, translated by A. Zawadzki, Universitas, Kraków 2007, pp. 441, 442.

[84] Ibid., pp. 444-445.

[85] P. Juszkiewicz, Od rozkoszy historiozofii..., op. cit., pp. 34-35.

[86] D. Hume, Sprawdzian smaku, in: D. Hume, Eseje z dziedziny moralności i literatury, translated by T. Tatarkiewiczowa, editing and introduction by W. Tatarkiewicz, PWN, Warsaw 1955, pp. 206, 212.

[87] D. Hume, O pisaniu esejów, in: D. Hume, Eseje z dziedziny moralności i literatury, translated by T. Tatarkiewiczowa, editing and introduction by W. Tatarkiewicz, PWN, Warsaw 1955, pp. XII-XIII.

[88] D. Hume, ibid., p. 207