Closing the year 2021, rather peculiar issue of Art Review featured a project of a Pakistani artist, Bani Abidi, entitled “The reassuring Hand Gestures of Big Men, Small Men, All Men”. The artist gathered frames of photos showing hand gestures, in the most part done by famous world politicians: Ronald Reagan, Alexander Lukashenko, Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, Jair Bolsonaro, Kim Jong-un, Donald Trump and others. The collection opens with an index finger gesture – a commandment gesture for drawing attention, then a gesture of military salute, a gesture of an open and a clenched hand. And, finally, a gesture of fingers spread in a “V” letter sign – the victory gesture.

Contrary to the title, there are not everyone’s gestures – we see no gestures of common people, but rather the gestures of the chosen, great people; politicians representing a firm hand ruling or even totalitarian one. The gestures collected for the project constitute a spell of power cast on people who are subjects to the rule. The extended finger points the way; salute expresses readiness to fight against enemies; the open hand – amity towards friends and allies. And lastly, the “V” sign – joy of victory, a political victory. Looking at the last gesture I thought about Poland and its history. There are no Polish politicians among the heroes of Abidi project, though it was in the 1980s Poland that the gesture of V-shaped fingers was truly iconic. Still, it was not a gesture given from above, introduced for politicians trained by specialists, but quite the opposite – it was a flower blooming with hands of ordinary people and it could be plucked by those who had the courage and will to represent them. In a way, it was a peaceful resistance movement, brimful with serenity and hope for victory.

It first appearance took place at the beginning of the decade, during the Gdańsk Shipyard strike in August. On the poster of the film documenting the strike, “Workers 80” by Andrzej Chodakowski, Andrzej Zajączkowski and Grzegorz Eberhardt we see another gesture – a fist clenched in rightful anger. It is a revolutionary gesture, used by left-wing and anarchistic organisations, threatening the authority. However, in the last seconds of the film we can see a different gesture – splayed fingers raising above heads of the crowd listening to Lech Wałęsa’s words. It is not a threat but the response to good news about signed agreements, greetings expressing joy and hope for the agreements to come true.

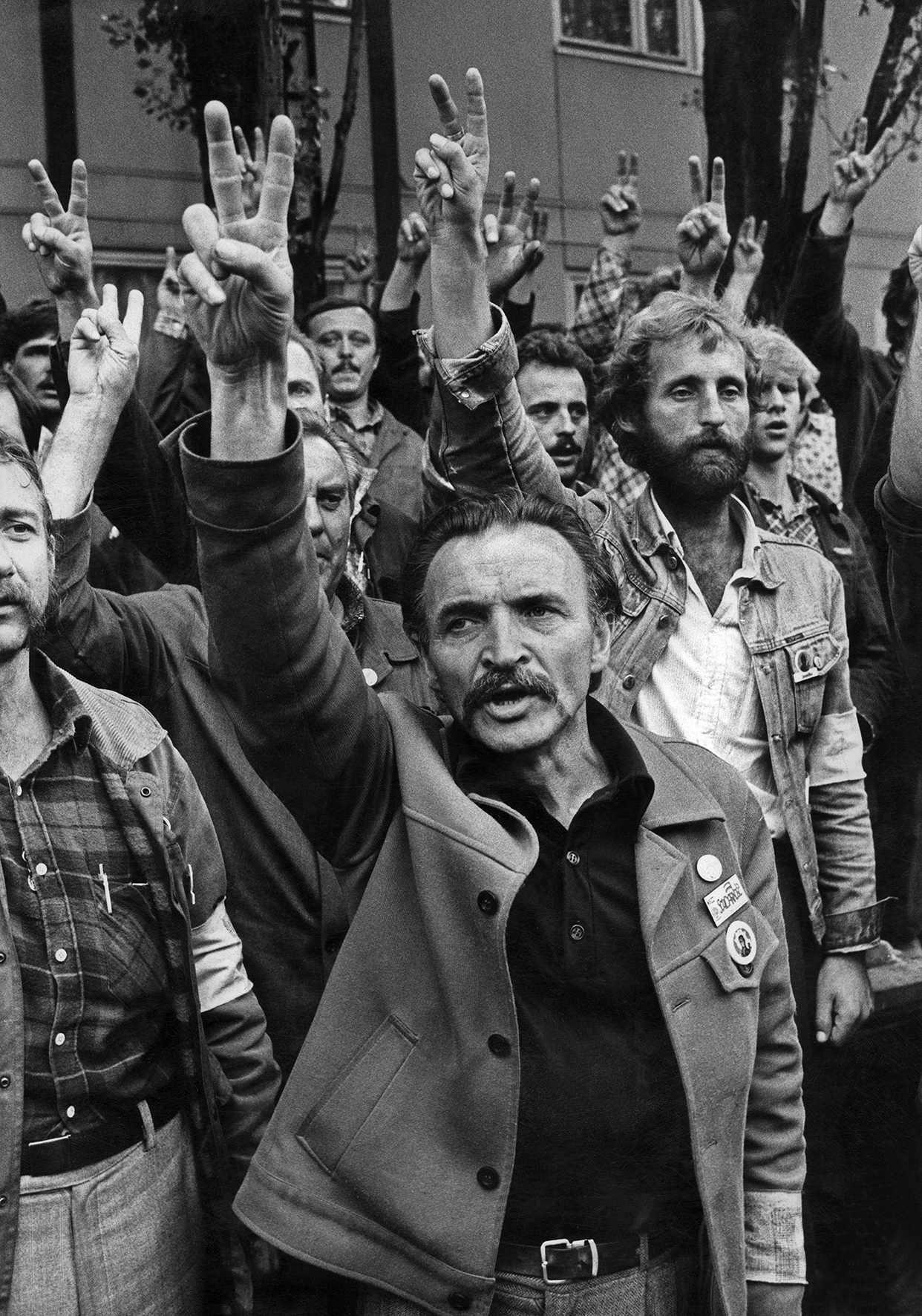

Similarly, a famous photograph by Erazm Ciołek entitled “Strike. August 1980” is showing a crowd of anonymous workers raising their hands in the victory gesture. Let us focus on Erazm Ciołek for a while. This photographer, who started his work with artistic and abstract photography, exhibited in 1960 at the Crooked Circle Club, had been working on reporting formula of a single-shot column for two years following exhibition. The formula was supposed to facilitate telling a one-frame story using not only narration elements but also the formal ones, specific to black and white photography. A milestone event that enabled to use such formula was a trip to Gdańsk Shipyard in August, 1980. From that moment on, Ciołek had become a photographer of Solidarity, through its thick and thin, as well as people connected with it, until the year 1989. There are two artistic photography books that are related to this period and constitute a unique record of the decade. First, released in the middle of 1981 is entitled “Stop, kontrola” (“Stop, control”) and it is a small album documenting the strike in August. However, it is a committed documentary, explicitly taking the side of workers on strike, their families and representatives with Lech Wałesa at the head. The other publication, “Polska. sierpień 1980 – sierpień 1989” (“Poland. August 1980 – August 1989”), released in 1990, the photography book documenting and concluding the decade, had similar character. It is on the cover of the second publication that one can see the photo of Gdańsk workers raising their hands in the victory gesture. Choosing this picture by the artist himself is very telling – it is a symbol of the decade. Though in the year 1990, it was not just a gesture of growing hope, but a hope fulfilled. Yet, in 1981, it was not so obvious.

Fot. Erazm Ciołek, Strajk. Sierpień 1988, © A. Ciołek

On December 13, 1981, hopes for freedom were violently suppressed – a fact that has been concisely expressed by Krzysztof M. Bednarski sculpture entitled “Victoria-Victoria” (1983). It is a marble hand showing the title gesture. The thing is, the bottom parts of the fingers are cut. It is an interesting paraphrase of famous words spoken after Poznań Uprising in June, 1956, by then Prime Minister, Józef Cyrankiewicz: “let it be known to each provocateur or madmen who dares to raise their hand against people’s government, that such hand will be chopped off by the authority in common interests of working class, working peasantry and intelligentsia”. The piece of art is not merely a simple illustration of words, a transparent sign, but rather a profound symbol, which does not interfere with its universal understanding. The marble hand with chopped off fingers is not only a sign of decapitated Solidarity but also a sign of a peaceful protest – a particular gesture of a raised hand in the interest not solely the working class, peasantry and intelligentsia but the entire Poles’ community which, despite attempts to break it, cannot be erased. Similarly to relics of old cultures – the shattered fragments of old Roman sculptures placed in museum’s lapidarium – it will be a testament to what happened.

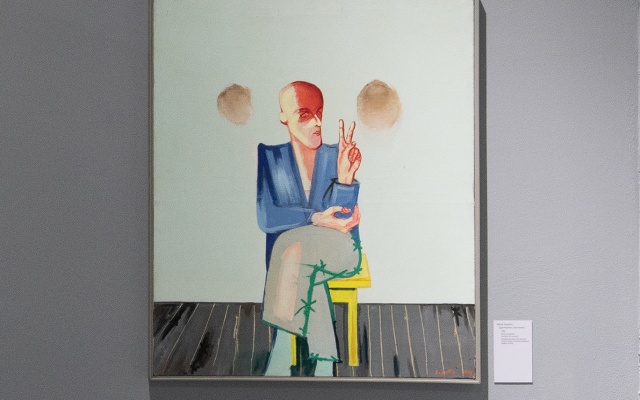

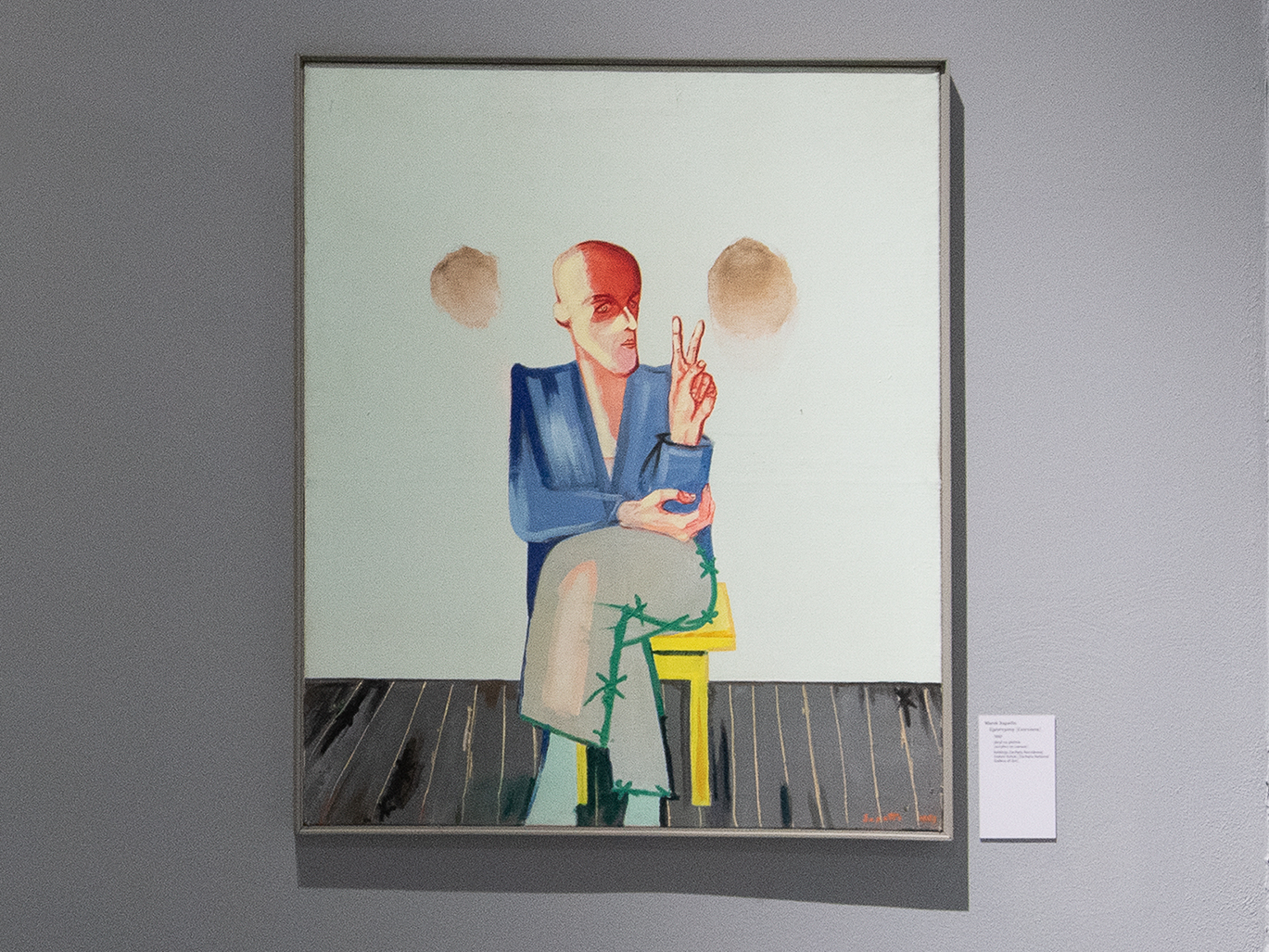

The victory gesture appears in multiple edits and versions of Independent Culture movement that can be found in CCA Ujazdowski Castle. One of the most interesting and significant examples is Marek Sapetta’s painting “Exorcisms”. The artist himself belonged to the most involved Independent Culture members. For his work, he was awarded the Independent Culture Committee Prize in 1983. It was him who initiated suitcase exhibitions in which miniature versions of artists’ paintings were transported and presented in the workshops, apartments, as well as on building walls, fences and hoardings. Such a suitcase, along with the selection of carefully prepared miniature versions of other paintings, was deposited in Archdiocese Warsaw Museum and is displayed at “Uncensored: Polish independent art of the 1980s” exhibition. “Exorcisms” (1983) is a miniature exactly like this; its large version was presented in the mentioned exhibition. It is this piece of art where we find the victory gesture of our interest.

Wystawa Nie ocenzurowano w CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, fot Adam Gut

The canvas presents a man sitting on a simple stool in the middle of an empty room. The man has a half-nonchalant posture – with his leg crossing the other, his hand supporting the elbow of the left arm, with the left hand raised ostentatiously showing a victory gesture, though it might as well be holding a cigarette. On the other hand, the posture could be interpreted as an expression of uncertainty, a person is curling up in a cold room, exposed to hostile looks.

Wystawa Nie ocenzurowano w CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, fot Adam Gut [zbliżenie]

In the background, we can see a pale-blue wall with two black holes at the heigh of the man’s head disturbing the monotony of the scene. Below, there is a dark plank floor. It seems that the man placed in this somewhat miasmic space is a subject to some kind of investigation, interrogation or is made to pose for a prison photo. He is placed, or rather seated, against the wall. Dark stains of dirt on the wall menacingly correspond with the man’s head. They can be interpreted as signs of previous interrogations or maybe these are shadows cast by the man’s head due to camera flash. This oppressive atmosphere is emphasised by a red stain covering part of the man’s head as well as right leg of the trousers’ edge highlighted with green line, creases of which resemble barbed wire’s ravels.

This character appears to be a distant echo of men, women and children placed against the wall in Andrzej Wróblewski’s “Rozstrzelanie” (“Execution”) series. What distinguishes this painting is not merely the sitting pose of the man, but it is the gesture of our interest that seems to turn this whole oppressive situation around: a cornered man in the middle of a prison cell is suddenly given dignity and strength to stand up to evil. Behold, the title exorcism – it directs a war gesture of victory against evil and subdues said evil, similarly to the sign of the cross overwhelming the devil.

In this past reality, the V-sign and the sign of the cross, intertwined. In the photograph taken by Grzegorz Rogiński, a photographer of those times, there are Masses for Homeland said by priest Jerzy Popiełuszko and we can see believers extending their hands – a show of hands, crosses held by some participants mix with fingers showing the victory gesture. In a sense, all these gestures became identical.

This is present in most important, independent exhibition of martial law years – “Sign of the Cross” organised in June 1983 in a church ruined during the Warsaw Uprising on Żytnia street. Among numerous artistic copies of the title sign, there is also a monumental victory sign interpretation found in “Wieczernik” (“The Cenacle”) piece. The installation survived only as a documentary, i.e. in a form of a photograph made by Erazm Ciołek mentioned above; the table and chairs in the lower part melted, or rather got buried under a pile of bricks and rubble left from the destroyed church, in a scenery appearing to be an abandoned cenacle. The sacrifice of the body and blood had already occurred, the apostles left the place, the time of the traitor and henchmen of false Din Torah has come. The situation from two thousand years ago has symbolically fit in the context of Polish history once more. The Polish cenacle of OSH Room in Gdańsk Shipyard – where words of truth and freedom that people longed for so much were finally uttered, where new kind of Polish community was established; one based on agreement signed by a pen with the image of earthly Vicar of Christ – was abandoned, betrayed, buried under rubble. Yet, even here, there is a promise for hope of resurrection. Rising up from the table, a white and red flag ripped in three places, with its upper part splitting into white-red “V”: the symbolism of the cross and victory united again.

Before long, the symbol of ripped “V” in white and red flag will come back in a more dramatic context, greatly contributing to messianic reading of Polish history. In October 1984, Public Security officers seized and brutally murdered priest Jerzy Popiełuszko. This event shocked Polish nation. Popeiłuszko’s pastoral activity was widely respected and admired in the society, despite being constantly discredited by state media also by the very spokesperson of then government, Jerzy Urban himself, who addressed Masses for Homeland with the following statement: “priest Jerzy Popiełuszko is an organiser of political hate session”. The news about kidnapping and assassination of the priest caused a widespread sadness and focus on praying, contrary to what then authorities wished had happened – the need of retaliation and revenge. Priest Jerzy’s funeral was attended by the crowd of over 600.000 people[1]. This general, Poland-wide stir caused by his death has become canvas for a diptych painting by Maria Anto entitled “Modlitwa polska” (“Polish Prayer”) where she presented hundreds of placards used during priest Jerzy’s funeral celebrations in a form of a painting collage. This painted documentary is by far the most explicit testament that the slogan dominating in the ceremonies did not say “death to oppressors”, as prompted by the Public Security officials[2], but “overcome evil with good”.

Jarek Tuszyński / CC-BY-SA-3.0 & GDFL

Priest Jerzy Popiełuszko was buried at St. Stanislaus Kostka Church in Warsaw. Before the present tombstone was placed – a stone rosemary designed by Jerzy Kalina – the grave that was a visiting place for great people from the entire world had got a temporary and more spontaneous setting. It was the very first version of priest Jerzy Popiełuszko’s grave, documented by relentless chronicler of the decade, Erazm Ciołek, where one can see a ripped, V-shaped white and red flag theme above the martyr’s grave, as though it was taken from “The Cenacle” installation, part of “The sign of the Cross” exhibition.

Year 1984 marks a high point of semantic significance ascribed to this gesture that objected to totalitarian lie and meant a peaceful protest – the communist authorities fought against the gesture more so than with a raised fist sign. They saw “the V” even in the broken altar bread held in the hands of a priest – the art assumed the meaning of the gesture to become the utterer of community’s feelings and desires. Two lifted fingers expressing hope for a better future might as well be understood as union of artists with the society. In case of Independent Culture movement, it would not have meant the independence from the receivers, the society, the community with which artists felt close relationship. A rare thing, and rather short-lived one.

In the second half of the 1980s, though the sign was still being carried by the society, it was gradually taken over by politicians and authorities. This moment was, once again, captured by Erazm Ciołek when he photographed two figures on the balcony of St. Stanislaus Kostka Church in Warsaw: vice-president of the USA, George Bush and the leader of Solidarity, Lech Wałęsa. In the picture, the leaders are standing next to each other, both making the same gesture but there are fundamental differences in their postures that symbolise crucial dissimilarities between the two sides of the Iron Curtain. Wałęsa, though he is a born tribune of people, handles this gesture a bit clumsily, which makes him even closer to the common people. Raising his bent arm, he is turning to the people gathered under the balcony who cannot be seen in the picture. He is smiling at them. Bush, a pure politician, is not looking at the people but the crowd. He is standing to attention, with his hand raised high – as though he was taking an oath after winning the elections.

Undoubtedly, there is a shift in meaning of the gesture: from the gesture of common people to the gesture directed to common people – the politicians’ gesture. It is exemplified in another significant photograph, taken by Grzegorz Rogiński this time, somewhat marking the end of the 1980s. It shows Tadeusz Mazowiecki – the first non-communist Prime Minister who was chosen after June elections in 1989. The Prime Minister is sitting on empty benches in government’s plenary chamber, extending his hand in a victory gesture towards Members of Parliament who, moments ago, entrusted him with a mission to form the government. This Mazowiecki’s “V” is a gesture of metamorphosis that carried the same message of unity and opposition towards the authorities and, at the same time, there was a new element there, new meanings we could also see in Bani Abidi’s project. A reassuring gesture of great people, ordinary people, all people. The art was finally able to search for its place between a community and a newly formed elite, or someplace else. It a story that reaches beyond the decade and one can experience it in “Uncensored” exhibition, a show one could close inside covers, similarly to a Victory sign.

[1] K. Daszkiewicz, Uprowadzenie i morderstwo ks. Jerzego Popiełuszki, Kantor Wydawniczy SAWW, Poznań 1990, p.14.