The entrance to the Gagosian Gallery, London was inhabited by unsettling presences this spring. There were a pair of calves suspended in formaldehyde solution; two flayed cows heads gazed at each other. A shoal of exotic fish – once vividly coloured – had lost its pigmentation and faded to tawny grey. It had, in artistic and market terms, acquired the patina of an Old Master. The exhibition Damien Hirst: Natural History (Gagosian, Britannia Street, London, closed May) displayed the preserved animal sculptures of Hirst and caused me to reflect on my experiences as a young artist in the 1990s.

When I was an art student at Goldsmiths College a couple of years after Hirst had graduated, his shadow loomed large. Tutors told tales of his unprecedented success while still a student. Hirst would send taxis to collect tutors so they could give him tutorials as he prepared works in galleries. Hirst’s Freeze exhibition in 1988 was held in a disused building in the East End of London. This was a partially derelict area in the docks around the Isle of Dogs. With the establishment of container ports on the coast of England in the 1960s, the docks in London fell into disuse. In the 1980s, the Thatcher government established grants and tax breaks for companies to convert and erect buildings, designating the district “Docklands”, a name that persists today. When Freeze took place, Canary Wharf Tower was being built and there were only a handful of occupied office buildings nearby.

It was this heady blend of new money, entrepreneurship, artistic confidence and industrial decay that provided the backdrop for the emergence of the Young British Artists (YBA) generation. The artists who exhibited at Freeze were all young (some still students) and knew each other socially. Some became noted as painters (Ian Davenport, Fiona Rae, Gary Hume) and others as new media and installation artists (Sarah Lucas, Anya Gallaccio). A number left the art world almost immediately after. The art caught the attention of advertising magnate Charles Saatchi. Formerly noted for collecting new American art, mainly Minimalism, Saatchi saw huge potential in the YBAs. He sold his American art, began to buy YBAs on an industrial scale and exhibited selected pieces at his gallery in St John’s Wood, a North London suburb (close to the famous Abbey Road studio, where The Beatles recorded).

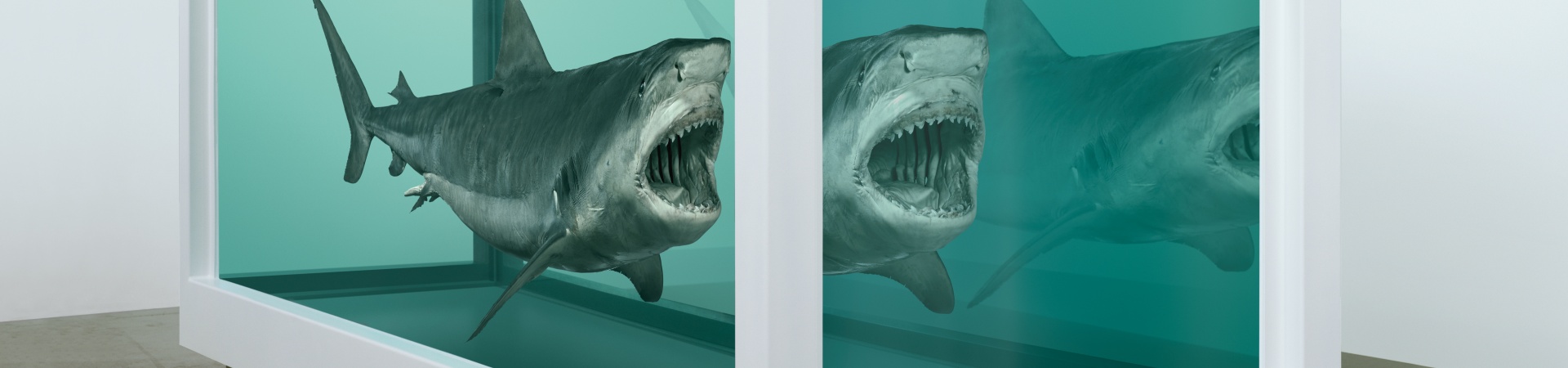

For the art students who studied in the early 1990s, Hirst was an impossible act to follow. Like others, I made the pilgrimage to see Hirst’s exhibitions, including at the Saatchi Gallery. The sight of The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) – a giant tiger shark in a tank – given plenty of space, is one of the most unforgettable experiences of the last 50 years of British art.

DAMIEN HIRST

Death Denied, 2008

Glass, painted stainless steel, silicone, monofilament, tiger shark, and formaldehyde solution

84.8 x 202.4 x 74.2 in 215.4 x 514.2 x 188.4 cm

© Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2022

Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd

Courtesty Gagosian

The space at Gagosian on Britannia Street, King’s Cross was in many ways reminiscent of the original Saatchi Gallery: a converted commercial building, with concrete floor, high white walls and visible overhead girders. The atmosphere of the Gagosian exhibition was part carnival side show, part medical museum, part 1990s art exhibition. A faint medicinal scent tinted the air. A burly security guard stood next to what was once a pickled sausage in a jar, while young female interns sashayed between desks, carrying iPads.

In the original 1991 Saatchi catalogue there was reference to Hirst living in a grim tower block but soon after Hirst hurtled into the art stratosphere. Within a few years of Freeze, numerous exhibitions, prizes and publications of great prestige made Hirst a multi-millionaire, with a jet-setting lifestyle and multiple studios producing art for display across the world. The rise of the YBAs was helped by Jay Jopling (White Cube Gallery), Maureen Paley (Interim Arts) and handful of influential gallerists. As students, we competed for the attention of high-profile artist-tutors. Michael Craig-Martin, the influential British-American artist and tutor, was so busy curating exhibitions and making art that he rarely had time for duties as a tutor at Goldsmiths College. Students aimed to get private-view invitations from tutors and would bring in catalogues to get them signed. The tangled romantic lives of artists, gallerists and figures in the art world became known to artists and students.

In the early 1990s, Goldsmiths College (and the wider London art-school scene) was a mixture of community and competition, with art students seeking to gain entry into the Saatchi collection and affecting a cool disinterested air (often simultaneously, to inadvertently comic effect). Young artists reacted against the advertising/newspaper-friendly YBA shock art, made of dead animals, frozen blood and gore photographs, by making earnest figurative paintings or abstract art. They set up galleries in council houses and promoted themselves as the next wave of British art, despite the fact the artists were the same age as the YBAs. They printed low-circulation art catalogues, hardly better than school projects, and sold them in limited editions. They founded nightclubs in the working-class Shoreditch district, East London. By 1996, the former industrial area of Hoxton Square was the hippest address in Europe. You could observe West Indian women and elderly Bengali men frowning in puzzlement at hipsters in tight suits, wearing vintage trainers and speaking into newly affordable mobile phones. These fashionable types (in rectangular spectacles and gelled hair) flitted between bars, galleries and restaurants that occupied reclaimed garment factories, as they scouted the hottest new art. In their wake, trailed anxious art students, attempting to look detached but ready to pounce at the appearance of a career opportunity.

Nothing bonded YBAs and the following generation – which have never had an official name, but we can call them the School of Hoxton Square – except a desire to do well. The School of Hoxton Square (or Hoxtonians) had little in common with the YBAs. They shared no mutual style, subjects or outlook. The savvy, self-interested, shallow YBAs and the atomised, drifting Hoxtonians were a perfect snapshot of changing Great Britain in the 1990s and 2000s. The entrepreneurial YBAs and the apathetic hipster Hoxtonians exemplified the rapid change that took place from 1988 to 1996.

By 1997, the new Tony Blair government was promoting YBA, Britpop bands and new fiction writers through official outlets, as the exciting face of “Cool Britannia”. In the art world, this reached an apotheosis in the 1997 Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy, London, which displayed Saatchi’s most memorable YBA acquisitions. The exhibition drew large crowds and much press coverage, including controversy. The painting of the child-murderer Myra Hindley was seen as distasteful and was physically attacked. The exhibition toured to Berlin and Brooklyn. In Brooklyn, a painting that included elephant dung in a depiction of the Virgin Mary was condemned by local Christians. It is revealing that at the time, most artist reactions to these two ethical issues were largely marked by indifference, even jeering at the “unsophisticated reactionary” responses to the art. There was no consideration at all about the sensibilities of social conservatives. It never crossed the minds of YBAs and Hoxtonians that there were ethical issues in play and that art should not necessarily trump other considerations. In retrospect, this moral blind spot is very telling.

It is notable that none of the artists of this period shared much in common with the artists who came before or after; they did not even seem to interact much with each other. None were rooted in community, place or faith. It was a template of British society to come: rootless, isolated, materialist, unidealistic, drifting. The British artists of the 1990s had frames of reference that went back no further than their 1970s childhoods, television culture, pop music, consumerism and American art of the 1980s. Much YBA art was plagiarised from art made by Americans and Europeans in the 1980s, which young British art students had encountered in catalogues and magazines. This art was adapted for mass consumption, remade and presented as fresh. The book High Art Lite by Julian Stallabrass laid bare this artistic bankruptcy.

In retrospect, one can see how desperately impoverished the art of the YBA and Hoxtonian groups was, in terms of intellectual treatment and thematic content. The Cool Britannia initiatives of the government – taken up with alacrity by the British and international media – succeeded in portraying Britain as young, urban, relaxed, accessible, creative, multi-ethnic and socially liberal precisely because the art, music and writing were cosmopolitan, shallow and hardly more than recycling of pre-existing material. The Chapman Brothers mimicked Dane Asger Jorn and American Charles Ray; Oasis aped The Beatles and Elastica remade The Kinks; Zadie Smith fused the style of American David Foster Wallace and classic British literature. It was clever, trite and superficial.

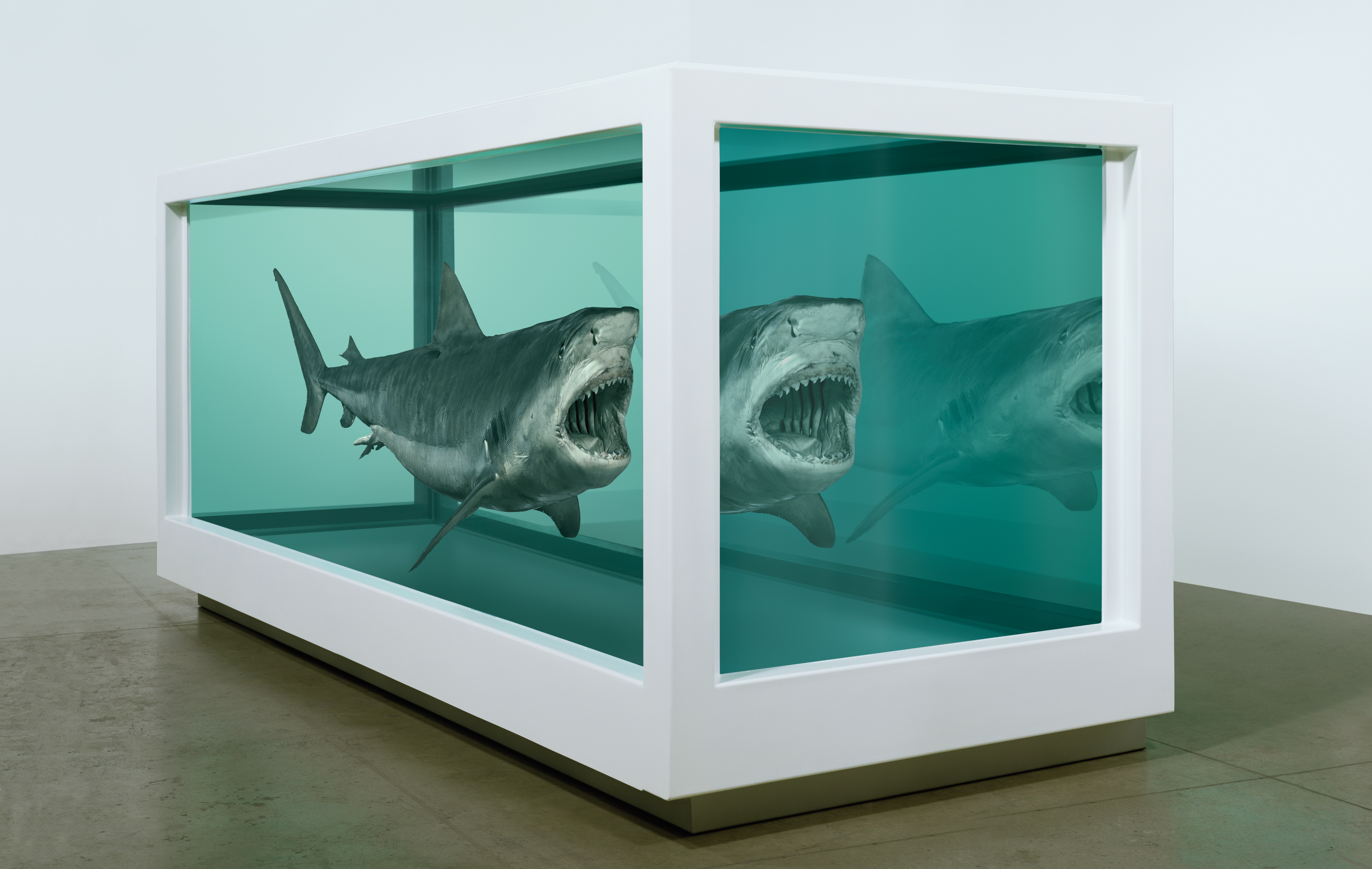

DAMIEN HIRST

Love is Blind, 2008

Glass, painted MDF, beech, aluminum, acrylic, fish, and formaldehyde solution

72 x 108 x 12 in 182.9 x 274.3 x 30.5 cm

© Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2022

Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd

Courtesy Gagosian

As the stages of amnesia and appropriation cycled ever faster, creators, collectors and critics seemed to meld into a cultural-industrial block similar to a fashion house that turned out new sensations each season, with products intended to last no longer than the season of their emergence. None of this was conducive to the formation of communities or traditions of value. The artistic references to pop culture that looked irreverent and fresh in 1992, now look vacant and irrelevant, like a faded poster for a third-rate summer party. While one could say that in their early years the artists experienced mild deprivation, this did not seem to breed a common outlook or shared values. Rather than building groups with powerful fellow feeling, British artists seemed to experience their poverty privately and personally and only briefly. This stage did not inspire them to make art of lasting value.

These artists came to schools in London, detaching themselves from suburban middle-class backgrounds. This is normal in the UK, where the professional art scene exists in the capital and nowhere else on any notable scale. It is hard not to conclude that secular, atomised, geographically detached, suburban individuals never formed true communities because their social background, art-school training and market conditions all determined that they never saw themselves in terms of any group identity. They did not seek a group identity because nothing in their backgrounds suggested that groups had worth. Knowing these individuals personally, I can say that had one raised with any of them the issue of group identity, nationality or religion, one would have faced derision or confusion. The only time YBAs and Hoxtonians united was when cheering the England football team or decrying the Conservative government. Liberalist or socialist outlooks were absolutely uniform. I never heard a word of dissent on that subject in the space of 20 years of interacting with young artists.

The ideas of normal craft or tradition were alien in that era. These were only adopted to be subverted or mocked. This was not least because the tutors of YBAs and Hoxtonians – as I personally remember – generally did not teach technique. They discussed ideas and critiqued art; they recommended other art and suggested books; they only infrequently explained use of materials. There was a palpable reluctance to inculcate craft, partly because some of our tutors did not make all their art. Some employed specialists to make objects or used commercial processes that they did not master. So, some art tutors could not teach technique because they did not know (and therefore disdained) craft. It is easy to see why artists today in Britain feel so deracinated, if they have not only not been taught craft but been warned off it as activity that is retrograde, limiting or exclusionary. We see in the West a ceaseless urge by progressivist activists to make every aspect of life political and to infiltrate, occupy and subvert every space of tradition. What seems a casual scepticism towards materials and techniques actually overlays a deep politically motivated hostility towards tradition, continuity and merit, that often sceptics themselves do not recognise.

Installation view, Damien Hirst: Natural History, Gagosian, Britannia Street, London, 2022

© Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2022

Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd

Courtesy Gagosian

Looking back from today, when many of us artists in Great Britain and the USA of a reactionary, traditionalist or conservative outlook are anxious to form communities, I can see the burden our upbringings have imposed upon us. Now, as we face institutions captured by cosmopolitan activist-administrators who loathe communities which embrace tradition and rootedness in the land and people, we have to make connections and make our livings in spite of concerted attempts to disrupt and demean us. The travails of simply existing as artists in a hostile environment is forging shared identities in a way that art-school attendance did not. Whereas art school taught British artists that they were individualists who owed nothing to family, nation, people or religion, simply trying to make art and sell it without the imposition of state values of multi-culturalism, liberalism, egalitarianism and cosmopolitanism is inadvertently bonding dissident individuals into communities. We are forming local groups (drawing landscapes or figures), exhibiting together, writing for (and subscribing to) newsletters, commissioning art works from each other, teaching classes and so forth. These are exactly the craft/community practices that art schools teach students are outmoded – the activities of amateurs and hopeless traditionalists, those enemies of true art.

Just as they did in Poland during the Communist era, circumstances drive political dissidents together in the West today. In Great Britain this comes partly from the fact that talented artists who do not meet minority-status criteria (non-Christian, non-white, female, homosexual, immigrant) are now routinely excluded from official commissions, exhibitions at public venues, receipt of grants, coverage in the mass-media and specialist press and other official lines of patronage. When people ask about how a vanguard is formed, we can say it is partly will and affinity, but it is also formed involuntarily. Vanguards come about partly because the talented and ambitious are excluded and shunned; they then associate with each other for support and company. Leading artists are selected by circumstances as much as through conscious choice.

Studying the history of German Modernist art, it is easy to see why the social and cultural excesses of the Weimar Republic repulsed many. In their zealous celebration of minorities, outsiders and non-conformists – and the promotion of secularism, humanism, anti-patriotism and anti-traditional values – the tastemakers of Weimar Germany provoked a backlash that led to the excesses of National Socialism. Looking at the celebration of minority-status individuals and the cult of victimhood, the West (especially the Anglosphere) is in danger of provoking yet another backlash. Without moderation and the opening of doors to dissidents, this backlash will be all the stronger and all the more uncompromising. Let us hope the door is opened voluntarily and generously opened to the dissident community, otherwise it will likely be opened by force and with anger.