In 2011, Bianca and Fabio from the Brave New Alps, who were on an artistic residency at Zamek Ujazdowski at the time, carried out a project which consisted in setting up a venue, a sub-residence in one of the Castle rooms. In collaboration with Paweł Jasiewicz, they designed and constructed a temporary wooden "room inside the room" and thus established a "support infrastructure," sharing the space in which they worked and lived during their residency with six other artists. Brave New Alps had surplus resources available to share with other artists. We, too, by organizing residencies at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, can mobilize funds raised from public donors, allocating them to artists and projects, and to the financing logistical and production support. In order to host, we need a place; having taken ownership of it, we can open it up to others.

Brave New Alps we współpracy z Pawłem Jasiewiczem, Mój Zamek jest Twoim Zamkiem, 2012. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

The Laboratory building resembles a Polish manor house. Compared to the neighboring building of the Ujazdowski Castle, it is quite small. In front of it there is an evenly mown lawn; behind it a paved road, a carpenter’s workshop and the pizza oven. The Laboratory is located on the banks of the Vistula River. This particular spot happens to be completely undeveloped, full of self-seeded acacia and elderberry. At this time of year, the air is permeated with a sweet and heady aroma. If it weren’t for the hum of the Łazienkowska Thoroughfare, you could think that you were on the outskirts of the city. And yet, this is only a few stops from the center of Warsaw. On the lawn there is an apple tree – Juliette Delventhal baked apple pie with its apples and Pipa Ambrogi made jam. Behind the building there is a pear tree – it is ungrafted but the fruit is tasty, well suited for preserves. In order to pick the fruit, one had to climb a tall ladder or lean out of the window of one of the studios.

Budynek Laboratorium na tle Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski, Warszawa. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

Juliette Delventhal, Paweł Kruk, We’re Like Gardens, 2012, Zdjęcie: Michał Grochowiak.

Juliette Delventhal, Paweł Kruk, We’re Like Gardens, 2012. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

If not for the fact that the building of the Ujazdowski Castle and the Laboratory provides work-and-living space, a large portion of the residency budget would be eaten up by the cost of renting the accommodation for the artists and there would be no surplus left over for the projects. Alternatively, we would be only able to host visitors from Western countries that provide artist back-up and fund the residencies abroad for their citizens. Notwithstanding that, there do exist artist-in-residence programs such as New York’s Residency Unlimited, which has no residential quarters and functions more like an agency that brings together artists and local institutions interested in getting involved with art, to my mind what matters the most is the space. This is what makes it possible for the invited person to temporarily settle down and feel at home in the local context – and this is what makes residency different from other forms of travelling.

I came to realize this already in 2002, after having stayed at the Akademie Schloss Solitude for three months. The sojourn preceded working on the exhibition-cum festival A Need for Realism with the participation of artists from all over the world who at the time resided in Stuttgart. This was my one and only artist-in-residence experience and that was what shaped my thinking on this format for working with artists. Generously, Solitude organizes long-term – they used to be as long as two years – fully financed residencies for professionals involved in art,1 offering accommodation in one of the over 40 residential studios plus a workspace. The foundation makes it possible for the visitors to become part of the international artist community, attend events and themed symposia, as well as laying on technical and coordinator backup. In the case of this kind of residency, to "reside" means to be able to focus on conceptual work and research, on getting to know people and working closely with them.

Budynek Laboratorium, Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski, Warszawa. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

When I invited people to take part in the project A Need for Realism I offered them mini-residencies. Almost 30 artists came to simultaneously explore Warsaw and confront their experience with expectations. They were from western Europe, the USA, Palestine, Israel, and Russia. Such confrontations sometimes had unexpected results: when the collective Susanne Burner, Gary Ward, and Gregor Sander did not find, as expected, images of the People’s Republic of Poland, they upped sticks and set out further east – to Klaipėda, where they were hoping to find more afterimages of communism.

The resident artists stayed in the Sezam worker accommodation, every day commuting to Zamek Ujazdowski for the workshop that they were running, to attend lectures or work on their exhibition projects. The occasion made me realize – as did Wojtek Krukowski, then director of the CAA – that we had to provide a home for the artists in the Castle itself. That would enable their presence to enrich the local scene and their projects would give us an opportunity to gain a different perspective on ourselves. At that point we were not yet aware that the institutional space would stabilize the program financially and give it a firm footing for further development. In fact it was precisely the lack of in-house accommodation that had obliged many institutions from the former Eastern Bloc, which Akademie Schloss Solitude had been working with since 2005, to give up on their artist-in-residency activity. Some of them were interesting organizations such as Interspaces in Sofia or Kuda.org based in Novi Sad. The lack of infrastructure continues to be a challenge for the small, independent programs. Their survival often depends on obtaining finance for infrastructure and servicing it, since funding the accommodation for longer residencies can even double its cost. For a few years now, the idea that has gained popularity, especially in Japan, is for artist-in-residency programs to turn commercial by providing Airbnb and thereby acquire funds for the program and project logistics.

As early as the mid-1990s, Wojciech Krukowski had dreamt about creating an International Artistic Center in the Laboratory building. His vision involved providing the infrastructure: accommodation, studio, gallery, and auditorium. However, trying to convince any potential donor of the merit of such an enterprise ran into a brick wall, and so the Laboratory building for a long time stood unused, and the residency program remained pie-in-the-sky until the 2000s. In collaboration with Akademie Schloss Solitude and thanks to my own residency in Stuttgart in 2002, and our personal and emotional involvement in the project, finally the host arrived on the scene.

The Host

... or rather the hostess, who now had some idea of what kind of home she would like to create for her visitors. It took me a year to build it, from October 2002 until October 2003, spending what funds were left over from the project A Need for Realism and thanks to an 80 thousand zloty grant from the Ministry of Culture. At that time I was working closely with a fantastic team of young and very committed interns and volunteers such as Ania Rosińska, Ula Siemion, or Ola Berłożecka, who were sometimes modestly reimbursed for their work but mostly all they got was praise and the satisfaction of working for a righteous cause. Thanks to their persuasive power, the course was designed by a professional from Murator, the architectural publisher, and outfitted by the many companies that supported the project by donating equipment, chairs, floors, cutlery, kitchen utensils, and other equipment.

The studio in the attic of Ujazdowski Castle was completed toward the end of 2003. It was big enough for two artists. This intimate format determined the manner of working with the artist who together with the curator – since 2004, Marianna Dobkowska – worked in pairs, with the goal of implementing the project devised during the residency. That was a time of quite crazy and often breathtakingly expansive ideas. I recall Darwin singing Louis Armstrong’s "What a Wonderful World" from the façade of the Palace of Culture or Christopher Draeger’s hippie mini-revolution with its demos, trips out of town and "Egg Barem" that all provided the backdrop for his video; Revival Paradise – a remake of the film by Jarmush produced by Frederic Moser and Philippe Schwinger or the story about closed settlements by Sofie Thorsen. Many of these projects were accompanied by publications such as artbooks or fanzines.

Vitor Cesar, Iść przez miasto w stanie zamętu, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

Podróż kolektywu Hyslom, 2017. Zdjęcie: Hyslom.

Podróż kolektywu Hyslom, 2017. Zdjęcie: Hyslom.

Karolina Ferenc, Soiltopia, próbki ziemi pobrane w okolicy Zamku Ujazdowskiego. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

Christoph Draeger, Tropolicalia, festiwal-piknik, The OpenEGG przed Zamkiem Ujazdowskim. Zdjęcie: Patrycja Stefanek.

Christoph Draeger, Tropolicalia. Zdjęcie: Christoph Draeger.

Christoph Draeger, Tropolicalia. Zdjęcie: Christoph Draeger.

What made it possible to carry out such financially and logistically challenging projects were not, in fact, high residency subsidies (production grants ranged from 4000 to 8000 zł, so no higher than those that artists receive today) but the personal input from the curators and interns. At that time we understood our role not only as the now proverbial provision of "cozy eiderdowns" for our visitors (on occasions, we did have to offer our own that we brought in as the Castle had inadequate heating) but also as being responsible for the artists’ satisfaction and well-being.

On a wave of youthful euphoria, we implemented the projects of our guests, set up collaboration networks and put in a lot of resources, both from the institutions and from ourselves or provided by our families. We felt we had to. That made it possible to be able to boast the first institution in Poland to offer an artist-in-residency program. Nevertheless, it was hard to cope with the often ad-hoc projects put together during three-month sojourns by artists unknown in Poland. And it was an uphill struggle to secure technical and administrative backup. They treated the residencies as a scourge and extra chores, which the support staff were not inclined to carry out on behalf of artists whose grants were twice or sometimes even three times higher than the meager salaries at the Castle.

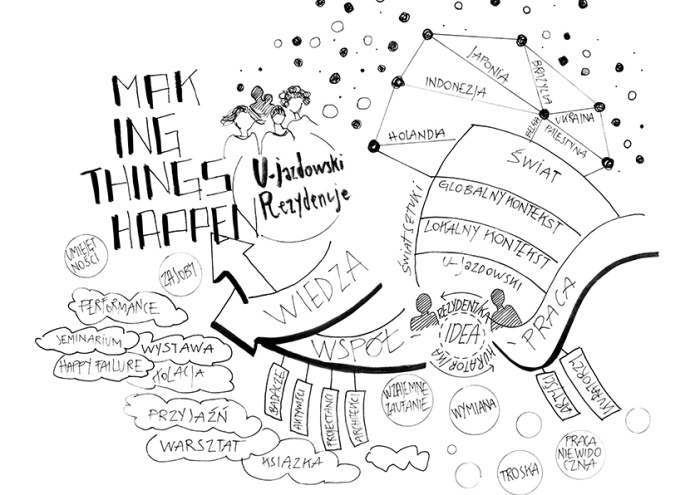

Diagram przedstawiający skalę działań programu U-jazdowski Rezydencje, Martina Dandolo.

These experiences translated into our concept of "residency curating" as a method of work considerably different from the role of the exhibition curator. The concept evolved in response to the hospitality practices of our all-women team. In that job, we used the same skills that we use daily as partners, friends, housewives, and mothers. Our brief is care, empathy, being sensitive to the needs of others and helping to build relationships. Some of the first residency projects ended in frustration (for example, artists having to face up to the fact that they would not be having an exhibition at the Castle) or our utter exhaustion, since we were at pains to take responsibility for someone’s sense of "satisfaction and well-being" – results that of course it is not in our gift to ensure. These intensive residencies that relied on personal relations led to a drying up of our network of contacts – because, after all, how often can one expect the same person to support the artists-in-residency out of the goodness of their hearts?

The Visitor

Today, most professionals tend to travel, seeking new opportunities for personal development and for carrying out their projects. By the term "artist," which I use for simplicity’s sake, I understand a multitude of art practitioners, whether artists, curators, researchers or sometimes even people who have quite different day jobs such as managers, cooks, sound engineers, or theater technicians. When taking part in a residency, they for a time abandon their everyday life (albeit today it is perfectly possible to join in such a program without even leaving one’s own city) so as to work or swap experiences with other participants of a creative residency or with its organizers. The "privileged" status of this situation lies in the fact that the resident is in a kind of "unreal" reality – under the protective umbrella of the host institution and, depending on his profile, has a mentor and access to a group of other artists. He or she is provided with conditions conducive to individual work and given a chance to be creative away from the pressure of the art market and exhibition deadlines.

What, then, is an artist residency? These days it is quite hard to settle for a single definition as there are so many models and concepts of what it should be. It is certainly activity aimed at increasing the geographic mobility of people in the art world through providing a space or sometimes no more than a contact network and not always material resources for a specific duration. The raison d’être of a residency is linked closely to the presence of artists. Their curiosity, ideas, and fantasies determine the course of the residency and shape its dynamics. When viewed from the vantage point of the host institution, this is about generously bestowing not only stipends or cozy studios but above all help and trust. In this context, trust is understood as consent to take a risk involved in putting funds into a process rather than a final product.

Many artists use artist residencies as they provide a tailor-made environment for their practice based on working with local communities, participation, experimentation and venturing outside the studio. In a location to which the artist-in-residence has never been before, and without any knowledge of the local language, topography or people, exploration is much easier or indeed possible at all if one has a guardian. The programs define this function in different ways – sometimes this is a curator, and at other times an assistant voluntary worker or the producer. The resident’s curator or assistant becomes their guide in the unfamiliar reality, helping to build a network of contacts and filling them in on the new place of work, also doubling up as translator and, on occasions, becoming a friend.

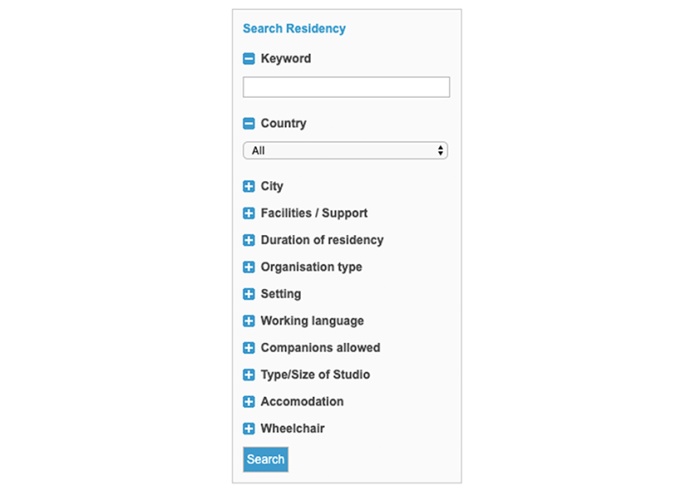

This is why in the context of residency we sometimes use the phrase "radical hospitality" – total, boundless hospitality. In other words, we give all we have of ourselves, without holding back. The fact remains, however, that in reality the relationship between the resident and the host organization does rely on "payback." Moreover, at various stages it is limited by ever more conditions. This is probably the most obvious at the point of selection. In open calls, residency programs openly name the terms of their "conditional" hospitality on their webpage. The successful applicant must meet formal and practical criteria. Google searches throw up a multitude of criteria that serve to rank residency organizations, which artists use when choosing the one that suits them. These include the discipline, the type of residency, companion (from spouse and children to pets), the type of studio, and stipend or grant.

Wyszukiwarka rezydencji ze strony www.resartis.org

Residencies stimulate multicultural journeys. Visitors and hosts often hail from different countries or continents and speak different languages. The presence of the visitor enables the host to gain a new perspective on their own reality as seen through the visitor’s eyes, or sample unfamiliar cuisine or customs. Nevertheless, a residency is an ongoing negotiation process that stems precisely from the social and cultural distinctiveness of both parties. And although as the organizers of residencies we would like to be open to the idea of radical hospitality, in reality a stance based on total abandonment of one’s own expectations and principles in the name of limitless openness to the visitor often turns out to be utopian.

We once hosted a curator who had the charms of Don Juan and a great talent… for creating his own legend. He soon struck up friendly relations with a curator, the woman who was in charge of his residency – they socialized together and she invited him to her place and to meet her friends. And he kept receiving invitations to take part in other projects. Unfortunately, in due course it transpired that his input into the planned activity remained no more than declarative. Moreover, the charming visitor began to break the prevailing rules of our residency, taking drugs on the premises or even subletting to third parties without informing the coordinators. It became very difficult to rein in this insubordinate resident who had in the meantime become a friend. To be a curator, manager, or coordinator of a residency must not mean giving up on one’s own needs. Friends who run such programs often tell me about visitors that break all the rules or become an encumbrance and not just in the professional relationship. I have often heard the sentiment expressed, "Why do I even bother to meet with him in my spare time, as I don’t even like him?!"

Considering the topic of hospitality in the context of contemporary artistic residency, it is impossible not to mention the issue of asylum-seeking artists. In 1993, in response to the murder of an Algerian writer in Algeria the idea was launched of organizing a network of cities that would be prepared to host writers in danger. In 2006 this network, having grown ever larger year after year, became ICORN (International Cities of Refuge Network). In Poland the ICORN member cities are Krakow, Wrocław, Gdańsk, and Katowice; they accept one or two writers a year for a longer sojourn; in 2019 Warsaw will also join the program. Since 2013, there has been an increasing number of initiatives that provide residencies for artists that hail from war zones or who are in danger due to their social or political activity, particularly if directed against the prevailing regime. Projects such as Safe Haven have developed to address the needs triggered by armed conflict and social protest in the Arab countries. In such organizations what counts most is not the quality of work but rather the desire to aid artists who seek an escape from repression or even death in their own country. Those who run such projects are faced with quite different challenges to those presented by traditional residency programs. Above all, they must cope with the traumatic experiences of their visitors and try to provide specialist psychological care. The formalities related to the logistics of such visits tend to be far more complex than with an ordinary three-month stay where a tourist visa suffices. Another vital obstacle is how the visitor copes with the local language or whether they have knowledge of such a language as English – without which they will find it difficult to settle down in a foreign country.

Juliette Delventhal, Paweł Kruk, Piec, 2011. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

And just as the residency organizations address the needs of contemporary artists, so the artists themselves have repeatedly raised ethical, political and social questions about the importance of hospitality in times of mass migration, the intensification of nationalist sentiments and the spread of populist language, which refers to the division into "us" and "them," the Others. Today, when the issue of the laws regulating the flow of foreigners and the regulations that refugees and economic migrants are subject to is extremely urgent and leads to social divisions, it is worth revisiting the idea of hospitality and the paradox that is revealed in the concept itself. For residency programs, hospitality is a fundamental idea, the cornerstone for such initiatives, linking them with concepts such as travel, home, openness, and making feel at home. Such a formula for work with artists offers hope that – thanks to close cooperation between the residents and the institution, and in response to a concrete need that has arisen in the world – in the future there will be yet new important projects that make a change.

Translated from Polish by Anda MacBride

BIO

Ika Sienkiewicz-Nowacka is a manager of culture, curator, and founder of the U–jazdowski residency program. She graduated from Inter-Faculty Individual Studies in the Humanities (University of Warsaw) and holds the European Diploma for Culture Management (Brussels). Member of the Programme Council of Akademie Schloss Solitude and Res Artis. Her research interests centre on the significance of residencies within the fields of artistic and institutional practice. She carries out projects in which visual arts become a tool of social change and are used to shape and promote alternative models of social development.

* Coverphoto: Juliette Delventhal, Paweł Kruk, The Oven, 2011. Photo: Bartosz Górka.

[1] Each artist gets a grant of 1300 euro a month.