What is the future for Polish-Lithuanian relations? The usual answer is, ‘Skvernelis this..., Morawiecki that…, Karbauskis says one thing, Kaczyński says another.’ But this is an outlook for the coming year, at most two years. A sceptic would point out that what everything boils down to in Polish-Lithuanian relations is as always the same old same old: the original spelling of surnames, the dual names of towns and streets, education, history, and Warsaw’s never-ending dilemma whether to prioritise strategic issues or the matter of the Polish minority in Lithuania.

In 2018, Lithuania and Poland celebrate the centenary of the restoration of their national independence – on 16 February and 11 November respectively, one can thus view the Polish-Lithuanian relationship with a perspective of a hundred years. Applying this timescale, one concludes that the majority of today’s problematic issues between the two countries stem from the dispute about Vilnius. Without it, there would be no issues, or at least they would not be as loaded as they are today. For many Poles, the issue is linked to the legacy of the Second Polish Republic – commonly known as interwar Poland (1918–1939); for Lithuanians – with the trauma of losing Vilnius and what they would perceive as their symbolic succumbing to its ‘occupation’ by Lithuanian Poles, should the latter be granted extended minority rights.

The conflict over Vilnius had been provoked by the model of nationality that the two countries had been pursuing. During the last century both Poland and Lithuania were created and represented in the mould of the utopian model of the nation state: one country, one nation, one blood. Reality has turned out to be more complex than that; it is not easy to delineate the territory of a state so that only its principal population and no other should live within its boundaries. In 1918, the majority of the residents of Vilnius – historically, the capital of Lithuania – were, apart from a small percentage of Lithuanians, Polish; in the rural area, the proportions were reversed, although, across the entire Vilnius region, Poles constituted approximately 50% of the population. This became the spark for the conflict, also military, arising from the territorial claims on the Vilnius province by Lithuania and Poland and demonstrated quite clearly that the national status quo of the two countries was fundamentally at the root of their acrimonious relationship.

Let us take another brief look at history. Lithuania existed as a Grand Duchy, and was later united with Poland through a shared monarch, and later still, as part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Poland also went through different stages of national status: Poland under the Piasts, and later the Jagiellonian dynasty during the Middle Ages, the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, then the Duchy of Warsaw, followed by Congress Poland in 1815. Each national model affected differently Poland’s relations with Lithuania.

Today, apparently Poland and Lithuania can only envisage their respective countries as nation states – as is evident from both of their celebrations this year of their anniversaries of national independence. One might form the impression that what is being celebrated is not the centenary of the restoration of the respective countries’ independence but a centenary of Lithuania and of Poland. For example, in Lithuania one often hears the slogan ‘valstybės šimtmetis’ – the centenary of the country. In Poland, there is much more emphasis on the regaining of national independence, yet the recent proposal to include the image of the Gate of Dawn in Vilnius on a Polish banknote – referred to as the ‘Sharp Gate’ in Polish and invested with national symbolism by both countries – shows that many Poles also view the anniversary as the centenary of Poland.

The era of nation states makes up approximately ten per cent of each country’s national history; as we know, the form that countries take keeps evolving. Thus, if we want to step outside current politics and take a broader perspective than one or two years or, at most, of reaching out to the next presidential or Sejm elections and to view Polish-Lithuanian relations with a futurologist’s slant, we must first review current trends in forms of nationality and extrapolate them into the future. What will Polish-Lithuanian relations look like in the year 2050? Let us start by considering what kinds of countries Lithuania and Poland are likely to become by the middle of the century.

In his book Diplomacy, Henry Kissinger, a prominent theoretician and practitioner of geopolitics, wrote in 1993 that in the 21st century the main political parts will be played by continental empires: the USA, China, India and Russia. In Kissinger’s opinion, Europe is faced with a choice: it must either become more united or become a political playground for other, more powerful entities and be left without a say in global politics. Pope Francis agrees; recently, he said that Europe either becomes a federation or it loses its political significance. Thus, Lithuania and Poland – alongside other European countries – have two alternatives in the face of the new challenges facing our continent and the European Union.

The first of these is to defend their sovereignty as a nation state and stand aside from the European processes of integration or perhaps withdraw from them entirely. In this scenario – without a robust alliance with the Western powers, sooner or later Lithuania and Poland will find themselves in the Russian and/or Chinese sphere of influence and with a de facto sovereignty in foreign policy acting in the interest of Moscow and/or Beijing. It is in those cities – rather than in Vilnius and Warsaw – that Polish-Lithuanian relations will then be determined. One can expect an action replay of the communist-era model, where relations between Warsaw and Vilnius were non-existent, and replaced instead by relations between the Communist Parties of Poland and the USSR and relations between the Lithuanian section of the USSR Communist Party and its headquarters in Moscow. Should European integration fail or should Lithuania and Poland withdraw from the EU integration project, one could expect the Polish-Lithuanian relationship to survive to the extent that it would be logistically useful in the struggle of Russia and China against the West. The remainder of each country’s political energy would be devoted to Lithuanian-Russian/Chinese or Polish-Russian/Chinese relations.

The other possible scenario for the two countries is to become part of a more integrated Europe. It is difficult today to define precisely what shape this might take, since such an outcome is to a large extent dependent on the decisions of the EU member states, taken in the next five or perhaps ten years. All that we can say for sure is that it will no longer be a confederation of national states as is the case today. On the other hand, it will not be a federation along the lines of a United States of Europe. The national traditions of Poland and Lithuania, but also for example Germany or Sweden are too strong for any of these countries simply to give up their sovereignty for the benefit of Brussels. It is likely that in the 21st century, the European Union will be transformed into a body in-between a confederation and a federation of nation states. The blueprint once proposed by the London-based weekly The Economist springs to mind: a European Union akin to the Holy Roman Empire, with sovereignty divided between Brussels and other European capitals, and the entire structure governed as subsidiaries.

Which scenario is the closest to the hearts of contemporary Lithuania and Poland? Notwithstanding the Eurosceptic rhetoric of Poland’s current government, Warsaw is not Eurosceptic in its policies, as is evident from the recent episode that involved Steve Bannon, a former adviser to Donald Trump, who is now attempting to bring together all the populists in Europe in order to bring down the European Union. According to the Polish media, it was precisely with such a proposal that Bannon approached the Polish Law and Justice Party, which, however, determinedly rejected it. Since, in the final analysis, apparently even the most Eurosceptic forces in Polish politics support European integration, one is justified in assuming that, when it comes to a showdown, Poland will opt to be part of the new, more integrated European Union.

The Lithuanian situation is much simpler. Its only Eurosceptic party – Order and Justice – is on the verge of collapse, and all the others are unequivocally in favour of Lithuanian participation in closer European integration. So far, Eurosceptic rhetoric has not gained much popular support, and the prevailing majority of the élites also favour the European option. To quote Albinas Januška, one of the signatories of the Act for the Re-Establishment of the State of Lithuania and once an éminence grise of Lithuanian politics: ‘Echoing Timothy Snyder, let me reply that the nation states of Eastern Europe, Finland and the Baltic region were unique, without precedent in western Europe. The experiment of nation states in 1918–1940 did not last long; history could not turn back. Almost everywhere else in Europe, there were empires (exceptions neither prove nor disprove anything). Nation states simply cannot exist for long; they have no economic base. They must either become empires or join others in an alliance in order to expand their territory and markets. Otherwise they will be defeated by globalisation. For this reason, our approach to Europe is the only rational one and the only one capable of guaranteeing the survival both of the Lithuanian nation and the country that it created on 16 February 1918, as well as the survival of Europe and democratic civilisation at all, under the conditions of competition with China.’

To these words by Albinas Januška one can add that today, nation states in Europe are too small to be able to tackle the ever-greater challenges such as the migration crisis and the commercial competition with China or the USA, and to ensure technological progress. And many in the European élites understand this, which is clear from the renewed discussions about reforming the European Union and about its future as a more integrated and cohesive entity.

For this reason, it seems quite plausible that in the next decade or two, nation states in Europe will be a thing of the past.1 By the same token, Lithuania and Poland as we know them today – thus, nation states – will have disappeared. We will have statehood in a new guise: Lithuania and Poland in the European Union.

Having at least to some extent postulated how the national status of these two countries may change, one can also venture to second-guess how, under different, new circumstances, relations between our two countries might develop.

First of all, it is likely that there will be a return to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, a European state that lasted from the 13th century until 1795, and expanded to include large parts of the former Kievan Rus, and what is now Belarus and parts of Poland, Ukraine and Russia. In the 15th century, it was the largest state in Europe, multi-ethnic and with a diversity in languages, religion and cultural heritage. It is also likely that – due to globalisation and economic integration – Poland and Lithuania will become much more culturally and linguistically diverse than they are today. It is quite possible that in 2050 there will be many more people with two, three or even more native languages; in consequence, it will become more and more difficult to define a Pole or a Lithuanian through language or ethnic origin alone. What will play a much greater role will be a person’s commitment to such values as freedom, human dignity and citizenship, and their voluntary identification with one or other country. In his novel Keep the Left Clear, the acclaimed writer from Vilnius, Józef Mackiewicz, presented his philosophy of the culture of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, introducing a category of ‘patriotism of landscape. He explained that ‘there are three kinds of patriotism: national patriotism, doctrinal patriotism and the patriotism of landscape. National patriotism takes an interest only in the people who inhabit the landscape, but not in the landscape itself. Doctrinal patriotism has no interest in either the people or the landscape; it only cares about instigating the doctrine. It is only the patriotism of landscape […] that takes a holistic view, because it includes the air, and the forests, and the meadows, and the marshes, and the people as elements of the landscape.’ Moreover, the experience of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the First Polish Republic (1569–1795) will find practical application in the creation of a new political identity for the Lithuanian and the Pole, one that will have to take into account a citizen’s loyalty towards Vilnius or Warsaw and to Brussels.

Secondly, it is likely that the topic of ethnic minorities will disappear from Polish-Lithuanian relations. Even if by the year 2050 it may not prove possible to solve all the grievances of the Polish minority in Lithuania, the chances are that in a renewed European Union, the differences between a Pole in Lithuania and a Pole in Poland, or a Lithuanian in Poland or a Lithuanian in Lithuania, or else a Pole or a Lithuanian in Spain will be minimal. This will be underpinned by EU legislation, which protects the culture and language rights of all the citizens of the European Union throughout its territory, legislation that is already being formulated today.

Thirdly, the longer Putinism continues in Russia, the more the current process of social disintegration will escalate; by the year 2050, this process may even result in political disintegration. Thus, by the mid-21st century, it is reasonable to expect that the dominant feature of Polish-Lithuanian relations will be issues related to the management of Russia’s decline such as making use of the new opportunities for the accession of Belarus and Ukraine to the European Union, restraining Chinese penetration of the region, absorbing the massive economic migration from Russia, dealing with the problem of chemical – and perhaps also nuclear – weapons that have fallen into the hands of non-state entities in the vicinity of Lithuania and Poland.

Lithuania and Poland have a history that goes back a thousand years, with only a handful of countries in the world being able to make such a claim. One of the key factors that have made such a long history of our countries possible has been their ability at critical times to take an overview of the forthcoming transformations on a continental scale and to adapt to them. Soon, another such moment will arrive; it is on its way already. Those who do not agree with the vision laid out in this text and who think that it betrays the national interests of Poland and Lithuania, and that we must search for another solution that would defend the total sovereignty of Lithuania and Poland must bear in mind that what we opt for will determine whether in the year 2050, Polish-Lithuanian relations will be shaped by Vilnius and Warsaw – or by Moscow and/or Beijing.

Translated from the Polish by Anda MacBride

BIO

Mariusz Antonowicz - Lithuanian Pole from Vilnius; a PhD candidate and lecturer at the Institute of International Relationships and Political Sciences of Vilnius University. He is a member of Polish Discussion Club. His interests include Polish, Lithuanian, and Belarusian foreign policy, and theories of international affairs. Antonowič currently writes a dissertation about Polish-Russian relationships in XXI century.

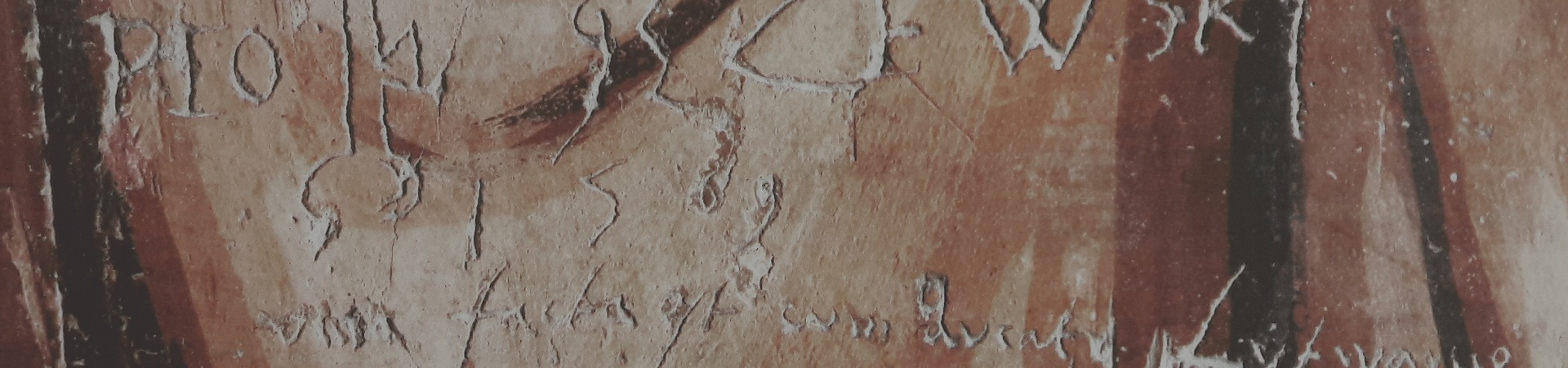

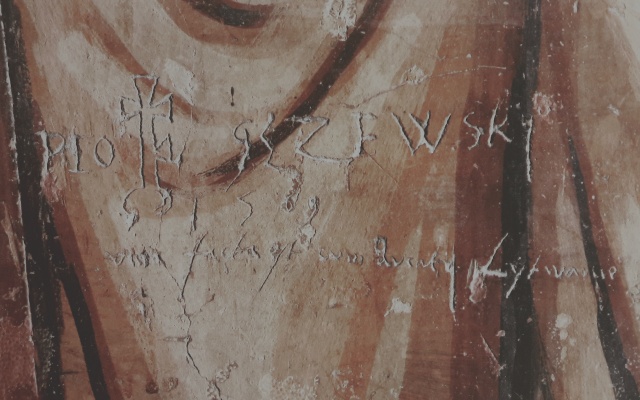

* Coverphoto: Pio(tr) / of Prus Trzeci coat of arms / Jeżewski / 1569 / unia facta est cum ductus Lytwanie, Muzeum Lubelskie in Lublin (Holy Trinity Chapel) – graffiti. During the union parliamentary sessions in 1569, a holy mass was held at the Holy Trinity Chapel in Lublin, asking for successful deliberations. In one spot, on the wall, the writing has been preserved immortalised by a witness of the swearing-in ceremony of the Union of Lublin - Piotr Jeżewski of Prus Trzeci coat of arms. Carved by hand in the Chapel, next to 203 other preserved inscriptions, on the cover of the stairs leading to the matroneum. The Union of Lublin is an exceptional case of the democratic integration of two countries, which led to the peaceful and inclusive coexistence of people of different ethnic and religious backgrounds.

[1] Euro-sceptics may claim that Brexit is proof that the new era of nation states is coming. However, if the United Kingdom leaves the European Union, that would mean that the country that had decided to leave the EU was the one that was the most opposed to the increased integration. Post-Brexit, there would be no other country of status equal to that of the UK that would be in a position to block the process of European integration.