First published in: Nafar Abad (with the introduction by Daniel Kötter), Kaveh Rashidzadeh, 2017, publisher: Bon-gah. Reprinted here courtesy of the Author and Bon-gah.

Introduction

Amou-Abbas1 resides in the Nafar-Abad neighborhood. Situated on the southern edge of Tehran, Nafar-Abad is part of District 20. Amou-Abbas was born in Nafar-Abad and still lives there. His house is situated in the center of the neighborhood at the intersection of the main alleyways. Despite almost being a “historic” neighborhood, Nafar-Abad has been subject to complete eradication due to its adjacency to a very important holy shrine of the Shiite religion, Hazrat Abdul-Azim’s shrine, a site of pilgrimage with ten million visitors annually which is in need of spatial expansion and development in order to accommodate the needs of its visitors.

The gradual deterioration and demolition of Nafar-Abad in the past two decades has been the consequence of this expansion plan. In this essay, I intend to illustrate how this suspension of conditions has led to a different production path for this space and, in turn, has brought out the traditional living qualities of the courtyard and inner private spaces and thrust them into public space. This is achieved by a detailed investigation into the space carried out by Amou-Abbas on the ruins of his maternal house in quest of a better quality of life. I will tell the rest of the story by reviewing relevant histories and a larger-scale analysis of the spatial conditions that provided the possibility of having a porous private and public life materialized in the courtyard-plaza of Amou-Abbas. Through mapping the inherent qualities and characteristics of the new urban landscape of Nafar-Abad, I will conclude that a creative, reciprocal, and beneficial coexistence for both the Holy Shrine and Nafar-Abad can still be possible by cherishing the qualities that exist in this semi-ruined landscape.

Amou-Abbas’ Maternal House as Part of Nafar-Abad’s Spatial Fabric

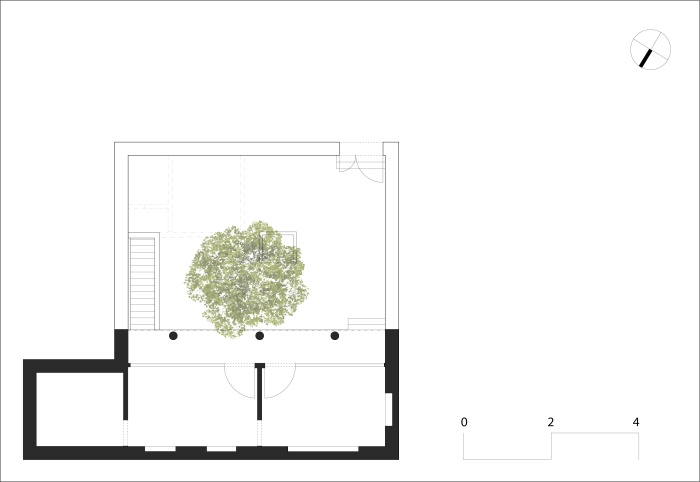

Amou-Abbas’s maternal house, located across the alley from his own, was an old, simple, and small single-family house with a courtyard built on a plot of land of less than a hundred square meters. The building was surrounded by three other neighbors on its northern, eastern, and western sides.

Obraz nr 1. Dom matki Amou-Abbasa, hipotetyczny plan narysowany na podstawie jego opisu na miejscu. © Autor, 2017.

The courtyard is an inseparable principle/element in the spatial organization of traditional Iranian houses. It unifies the entire house as a whole, while at the same time, helping to separate the desirable and non-desirable spaces as well as providing a cultural hierarchy of spaces. In the case of this little maternal house (as we have called it, see image no.1) there were two sets of spaces: a building on the north side of the plot and on the opposite side, under the surface of the entrance was the location of a toilet/bath and a storage space, connected to the courtyard via masonry stairs. The three connected main rooms of the building were joined via a stretched balcony with an elevation above ground level. The building had only one façade on the south. Thus, full sunlight poured into the rooms with the help of the intermediary balcony’s shadow. The courtyard that was in use throughout the day was equipped with two astonishing simple elements in the middle: a (white mulberry) tree and a small, shallow pond put to use in the arid, dry, and hot climate of the area. The tree covered a wide surface of about 50 percent of the courtyard with a play of light and shadow and the surface water cooled the air with an appealing breeze.

These types of houses, as the dominant typology in the original fabric of Nafar-Abad, constituted the total private spaces of the neighborhood, as the apartment typology was not a common form of living together even up until the 1990s in much of the country. So, the lifestyle of a traditional Iranian household was to live in total privacy inside the house (as it was said, “do what you want within your four walls”), while standing in contrast were the formal spaces of the alleys and other pathways belonging to the authorities, used as passageways. Therefore, the less porous the less possible it is to form public spaces by practicing common shared experiences in the public arenas of the “city.”

A visual reconstruction/representation of the maternal house is depicted in image no.1 as a schematic plan of the plot of land according to Amou-Abbas’s description presented on-site.

A History of Coexistence: The Hazrat Abdul-Azim Holy Shrine and Nafar-Abad Neighborhood

The strategic development of the sacred Shiite places such as the holy shrines has been an important spatial planning policy since the Islamic Revolution. There have been numerous cases of shrine (re)development projects throughout the country as well as other Shiite geographies and these developments have been projected on different scales according to the religious, historical, and socio-cultural importance of the Imam or Imamzadeh2 and the place itself. The more important the Imamzadeh, the more significant is the development project. In most cases, development and physical expansion have been regarded as equivalent. Such is the case for the Holy Shrine of Hazrat Abdul-Azim, a very important Imamzadeh with historical significance, and the Shrine is the capital city’s most important religious site and pilgrimage destination.

Hazrat Abdul-Azim’s shrine has been a pilgrimage destination for centuries up until today with over ten million visitors per year who come from all corners of the Shiite world. It was greatly influential in the rise of the ancient city of Rey, and its rebirth during the Safavid period in the 17th century, long after the devastating earthquake that tore the city apart in the Middle Ages. Both the Qajar and Pahlavi dynasties have recognized the Shrine’s importance in their own terms. The historic relationship between Tehran and Rey should also be considered. In the last revised master plan of Tehran, Rey (because of the Holy Shrine) is seen as the religious hub of the metropolis. Today’s development plan for the Holy Shrine is part of a long history, stretching back to the 10th century, of increasing grandeur of a modest shrine.

The burial location of Hazrat’s corpse is said to have been in the agricultural garden fields around the old city of Rey. In recent centuries during and after the Safavid period, the gradual growth of small settlements of migrants, pilgrims, and nomads around the Shrine led to the evolution of neighborhoods such as Estakhr, Vali-Abad, Nafar-Abad, and Hashem-Abad. The economy of Rey city has been greatly influenced by the economy of pilgrimage. The Nafar-Abad neighborhood was formed adjacent to the south-east side of the Shrine, and due to its expansion, has finally reached the Shrine.

There are two narratives on the origins of the name of Nafar-Abad according to Masjed-Jamei (2013). The first narrative refers to the migration of nomads of a tribe called “Nafar” as a tribal branch of the larger Qashqai nomadic tribe in the Safavid period. The second narrative speculates that the people of Nafar-Abad were cameleers and because “nafar” is the word for counting camels and hence the name of the place. Since pilgrims needed caravans as means of transportation and caravanserais for accommodation, the cameleers who did this business settled their families in this place. Both narratives may be correct and even related.

If not being the oldest neighborhood of Rey, taking a glance at the physical fabric of Rey shows that no other area in Rey has maintained its pathway structure as much as Nafar-Abad. There is a small religious institution in Nafar-Abad called “Tekkieh Nafar-Abad” which was initiated more than 375 years ago (Masjed-Jamei, 2013) a sign that a social and spatial fabric existed there at that time. Today, since Rey has joined the metropolis as the 20th district, the Tekkieh of Nafar-Abad is considered the oldest Tekkieh of Tehran as well.

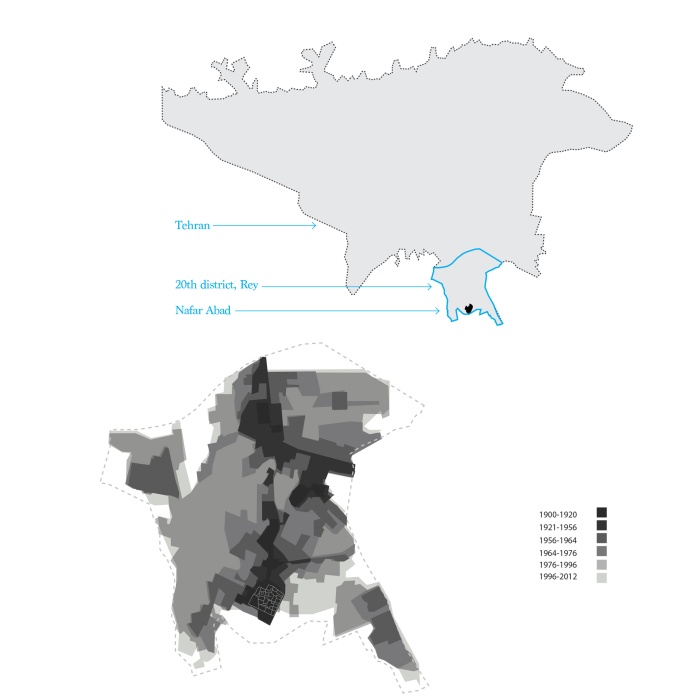

Ilustracja nr 2. Na szaro ukazano okresy historycznego rozrostu miasta Rej. Ścieżki Nafar Abad oznaczono białymi liniami. Mapę sporządzono na podstawie map Fatemeh Torabi Kachousangi z 2014 r. © Fatemeh Torabi Kachousangi, Kaveh Rashidzadeh.

Nafar-Abad is located on the southern margins of Tehran. In its surrounding landscape, there are agricultural fields, and a bit further down south, the wastewater treatment plant of the metropolis is at work. Image no.2 shows the map of the historic stages of urban growth of Rey, or the 20th district, from the 19th century to today. The darker the area, the older its fabric is. The darkest are located in Nafar-Abad and it is evident that the growth of the city has been inclined toward the north, toward the magnet of the capital city.

The Expansion Plan for the Holy Shrine and the “Special Plan” for Nafar-Abad

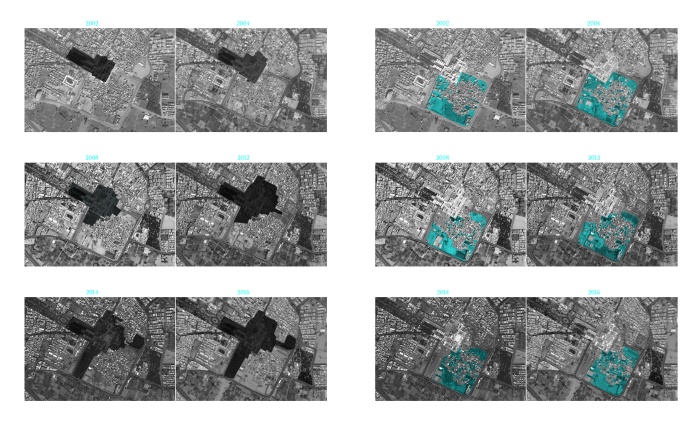

In 2006, the Iranian Supreme Council for Architecture and Urbanism approved the “Commission of Article 5” which defined what was to be called “decaying urban fabric.”3 With this definition, Nafar-Abad in general, and in our case the maternal house, would be labelled and viewed as deteriorated fabric subject to intervention and most probably eradication. This was added to the already envisaged “project” for the expansion and development of the Holy Shrine and Nafar-Abad being viewed as an important resort for strategies of expansion. By inspecting the satellite images that Google has benefited the public with, we can observe the spatial changes that have occurred over the past fifteen years. The results of this observation are two interrelated processes that have taken place since 2002: the expansion of the Shrine and shrinkage of Nafar-Abad. Consequently, two sets of maps have been drawn and created based on the satellite images.

Ilustracja nr 3 3. Mapa rozwoju przestrzennego sanktuarium (lewa część) oraz procesu rozbiórki Nafar Abad (prawa część) w latach 2002-2016. Na podstawie zdjęć satelitarnych Google. © Kaveh Rashidzadeh, Sahar Shirfard, 2016.

The first set of maps show the expansion of the Holy Shrine (image no.03, the left half). We can clearly see that throughout the past fifteen years, the Shrine has extended its territory in an axial manner in eastern and southern directions. In the second set of maps, we can follow the pace of demolition of Nafar-Abad’s fabric, and the disappearance of houses from the map. This pace of demolition accelerated from 2010 to 2014. In late 2012, the maternal house was demolished.

The gradual disappearance of Nafar-Abad’s houses would reach a threshold of structural change in the material fabric of the neighborhood (maps on the right half of image no.03). From 2002 to 2010, we can see that the dense “organic” fabric has some holes here and there, granting some more breathing room. From 2010 to 2014, the fabric moves toward the threshold of tearing apart: from wide gaps and cracks to the scattering of the fabric into some pieces each containing a number of houses attached together. However, at this point still there is a sense of continuity in the fabric.

The 2016 map shows that the destruction of the neighborhood has formed a new spatial structure consisting of detached houses (in other words houses are becoming villas), while new open spaces have replaced the demolished houses in between them to emphasize the ruined condition that is taking over. The new spatial structure that is composed of involuntary “villas” standing apart between the ruins and open spaces is different from the traditional (courtyard) houses, which used to be adjoined back to back. The encroachment of open spaces means that the bulldozed houses are now the property of the Shrine, and the appearance of asphalt is an important environmental sign of this razing. At this moment, the spatial condition of this neighborhood is special and if it stays as it is, there will be interesting potentialities for landscape architecture and urban rehabilitation and renovation to find a resolution to the complex situation that Nafar-Abad has been put into. In the following paragraphs, before proceeding on to a detailed investigation on Amou-Abbas’ creative operation, I will describe this situation and explain what these potential outcomes are.

In the early 1990s, the project of the Shrine’s development began and since then, the two neighborhoods of Hashem-Abad and Nafar-Abad, as the closest neighbors in the vicinity of the Shrine, were subject to expansion policies being undertaken by the authorities. The routine in such projects is that the land is bought by the authorities, and then the building is bulldozed until most of the land parcels are acquired so that the ground is ready for the realization of the urban development projects. Meanwhile, during the process, no household is permitted to sell their property and consequently the land price drops. Over the years, the neighborhood’s halt situation and gradual drop of property value together with natural decay, as well as the decay which stems from the despair of a suspended future, living in between ruins, in a neighborhood that has been labelled as “deteriorated,” these all culminate in the residents saying goodbye to their homes and migrating to other places. This abovementioned suspension era has been lingering for almost twenty years.

In the 1990s, Tehran’s mayor, Gh. Karbaschi, embarked on a new form of spatial production, which is commonly called “selling density.” It encouraged Tehrani people to demolish their two-story houses and build multi-story apartments, by paying more to the municipality in order to obtain more space: the municipality earns some money, property holders get richer by selling the surplus apartments. This strategy has since marked the increase of an apartment lifestyle and the disappearance of life with a courtyard throughout Tehran and to some extent the whole country. None of these things happened in Nafar-Abad and its residents did not experience the practice of buying density to build and sell apartments.

Contrary to the current trend, the reverse has happened in Nafar-Abad. The example of Amou-Abbas’ maternal house being categorized as “deteriorated” according to the 2006 Commission of Article 5 can be applied to the whole 12 hectares of Nafar-Abad. Concurrent with this total demolition plan, there are plans for the future of the site. In 2013, a commissioned consulting firm proposed a future plan for Nafar-Abad. In the past years, despite the introduction of paradigms of “sense of place,” “participatory planning,” “urban regeneration,” and “social sustainability” of the experts, the proposed project (called “the Special Plan”) has not been able to implement such theories and objectives. Instead, it confirmed the complete eradication of the neighborhood with a plan to create a landscaped park with a lake (or lawn) combined with some underground hotel apartments and commercial spaces.

The explanation of the project’s preliminary design has two lines of reasoning. That somewhere between 500 to 900 years ago this area was all gardens and agriculture landscapes, so it should return to that original flat landscape which leads to making the Shrine look great from the south. The other line of reasoning goes that the people of Nafar-Abad are not the most “original” citizens of the city of Rey, so there is not a big problem to entirely clear the already half-demolished site. There are also two explanations stating that the Nafar-Abadi residents are not so “original”: that about 400 years ago, Nafar-Abad’s people were newcomers compared with the example of the Estakhr historic neighborhood (of which today there is no remaining spatial trace), and that in recent years, there has been an in-migration of Afghani people (which is itself a consequence of the top-down suspension policies).

Ilustracja nr 4. Plan przedstawiający faktyczny stan dzielnicy w 2016 r. oraz umiejscowienie miejsca z sofami pomiędzy ruinami i ocalonymi domami. Jasnozioelone linie pokazują starą strukturę ulic zmienioną w tej chwili w trudną do zdefiniowania otwartą przestrzeń. © Kaveh Rashidzadeh, Sahar Shirfard, 2017.

Let us forget about this envisioned future that has been put on hold by the municipality and try to read the existing situation which is interesting enough for a meticulous observation. The material fabric, which stands now in Nafar-Abad is composed of scattered groups of buildings or houses detached from their old neighbors and are now free to have four façades. The new urban landscape is a landscape with a large portion of open spaces. The open spaces are of two major types. One is the space in between buildings combined with ruins, which provide a sense of being surrounded by a clear geometry left behind by the vanished buildings. The second type of open spaces is the vast areas that have combined a greater number of demolished houses. Asphalt helps for better recognition of the second type. An ensemble of these multiple open spaces that shapes this special landscape looks like a collection of large and small piazzas and squares of historic cities put together in a small area. The façades of these little piazzas, created out of destruction, have their own special aesthetics. The aesthetics of ruins (which in Western culture has benefitted from centuries of theorization) is combined with the revelation of the past social life that is now gone. The remaining buildings have still kept something from their bygone neighbors within their bared façades. The (new) façades expose that there are still some (social) ties between the buildings despite their present detachment thanks to the revealed sections of their interior space carved on the façades’ surface. The private enclosed interiors are now exposed to the public, telling the stories of the past to the curious observers. These remnants interestingly show that Nafar-Abad’s fabric has not been valueless (i.e. poverty stricken). These sections of the past lives of Nafar-Abad’s people are indeed historical sections of the people who used to live in this geography, if we use a museum lens and have in mind concerns for cultural preservation. The museum idea corresponds to the force of tourism already there in the vicinity as well as the ruins correlating with the cemetery and the theme of death, which also resides in the surrounding landscape. If the present remaining buildings could be renovated in an urban rehabilitation framework, then the necessities for hotel apartments and commercial space that is intended in the plans can find its place within the existing situation.

Ilustracja nr 6. Ruiny w Nafar Abad, © Kaveh Rashidzadeh, 2016.

Ilustracja nr 5. Ruiny w Nafar Abad, © Kaveh Rashidzadeh, 2016.

Bringing out the spatial memories of the inside private space to the outside public space can be the starting point in shaping and making a new space which is in continuity with its past without any nostalgia for its total loss. What Amou-Abbas has done, I think, is to discover this keystone and show the possibility to realize this starting point. His act can be a release from the theoretical and practical dead ends that the future of Nafar-Abad is facing, and perhaps could be a mock-up for a larger scale action.

Amou-Abbas’ Action (Act)4

Ilustracja nr 7. Dziedziniec Amou-Abbasa. © Kaveh Rashidadzeh, 2016.

Image no.08 shows the plan of the space that has been built by Amou-Abbas. I have called the space “Amou-Abbas’ public courtyard” since the name suggests the contradicting qualities of public and private simultaneously inherent in this particular space.

It is a public space not only because it does not have walls or fences and not just because everyone (the public) can enter its “borders” and be there, but because there can be found certain qualities of a public space, such as spatial qualities that urban (landscape) designers are eager to be able to create in such spaces. This space looks like a stage, as if a theater play is going to be performed here now and another day another play with a different setting and design. The mobile phone photos that Amou-Abbas has sent to me via the Telegram App visually affirm that the stage quality of a public space existing in this tiny, cozy place is in accord with everyday life and the events that take place. For instance, during the ten days of religious mourning for Imam Hussain or the festive celebration for the birth of the twelfth Imam, the courtyard plays its role by adjusting its space to the event’s characteristics. For instance, the floor is covered with rugs and carpets, scaffolds are covered with textiles and lights, and sometimes loud speakers and other equipment are added to the backdrop. Also, during daily life, there are some changing elements which slightly alter the mood of the place: the furniture (currently sofas), the gardening (the choice of flowers and plants), the color of the little pond, and the seasons which represent themselves via the mulberry tree.

This public space is also a courtyard, or better said, it still persists to be a (private) courtyard. To describe the socio-spatial qualities of the Parisian streets, Walter Benjamin uses the allegory of the interior space of the living room. What has occurred in the case of Amou-Abbas’ courtyard is perhaps the literal transformation of a living room which is the courtyard into an (urban)5 public space, and we may hypothesize that what makes it attractive and provides it with a full sense of place is this persistence and rebirth of the courtyard after its walls were demolished. This courtyard is not a general courtyard, either; it is the courtyard of Amou-Abbas, thus a semi-private space, because the degree that he has appropriated the space would not allow it to become totally public. First, he has designed and garnered the place. Second, in the neighborhood everybody knows that this place “belongs” to Amou-Abbas’ family, and in reality, people who get the chance to use this space are those who have gained, in some way, permission to stay there. Third, because his house is located just in front of the courtyard he and his family can have their eyes on the street and hence keep the space under supervision. From another perspective, Amou-Abbas has extended his property and territory by acquiring and adding this lost space to his own private space. This can be seen as an effective strategy to make the best out of the suspension conditions that he has to work under: agency versus structure.

Ilustracja nr 8. Plan zagospodarowania przestrzennego dziedzińca Amou-Abbasa. © Kaveh Rashidzadeh, Sahar Shirfard, 2017.

The Design’s Special Features

The courtyard’s area has been demarcated from the all-asphalt surroundings with five soft techniques of border determination: height and material difference, use of sitting platforms, flowerbeds and curbs, and movable furniture. The courtyard’s floor is two steps below the main asphalt ground, which is paved with a wide selection of tiles.

On the eastern side, which borders the blank façade of the neighboring building, an elevated cement platform has been built, which in some parts has been covered with scattered tiles. The long continuous eastern platform thus provides people with the possibility to lean back while seated and watch the sunset alongside the monumental view of the Holy Shrine. All the courtyard’s platforms can be seen in the photograph taken by Amou-Abbas (image no.09 –center right) showing two instances the platforms being used, sitting and resting, and selling fruit as well. As is obvious from the picture, the platforms and the flowerbeds can be combined when needed.

There are two entrances to this wall-less courtyard: one from the south, which is the main entrance and another from the north. The main entrance indirectly connects Amou-Abbas’ house to the courtyard and is marked with two lengthy descending stairs and two vertical platforms that create an axial attention to the monumental tree and the little pond intertwined. The north entrance is narrower and is placed at the axis of a north-south alley leading to the vast open space that envelops the courtyard.

Ilustracja nr 9. Zdjęcia wysłane autorowi przez Amou Abbasa. © Amou Abbas, 2014–2016.

At the core, there is the most important element of the courtyard, a tremendous mulberry tree, the only living remnant of the vanished maternal house. The horizontal spreading out of its branches has rendered the tree an expressive sculpture look in winter, while in the hot and dry summer of this climate the leaves cast a shadow of about 25 square meters on the ground, covering almost a third of the surface of the courtyard. This cooling shadow invites the passerby to stay for a while and cool down under the tranquility of the tree. Amou-Abbas’ self-made little pond is well intertwined with the tree trunk re-asserting the element of water onto the spatial setting of the courtyard. The tiered pond becomes more attractive by spreading the sound of water in the air. The presence of the four elements becomes complete with the placement of a brazier close to the eastern platforms. The brazier strengthens the sense of place of the neighborhood gathering which takes place around the fireplace, providing warmth in winter and the possibility of cooking and eating together (image no.09 center left).

The tree is the principal element in this assemblage that brings a social acceptance to the neighborhood scale for the success of this place as a place of daily gatherings in the public space. The image of a tree at the center of a well looked-after piece of land situated in a vast, open hollow space delights the passersby and attracts them to walk toward it since it reproduces a pleasant recognizable archetypical image that most Iranians remember well. In most human settlements of Iran, in villages, in historic centers of cities, in the main public square of a neighborhood, one can find an old tree and the social life that gathers around it: two men chatting while standing at one point, some old men sitting for hours in another, children playing, and a woman passes by. This is a village-like image of a small people who all know each other and are somehow relatives. So far, the image and the sociability that Amou-Abbas’ space has reproduced has had a strong rustic character.

Ilustracja nr 10. Dziedziniec Amou-Abbasa. © Kaveh Rashidzadeh, 2016.

However, there is a notable element in the assemblage of the courtyard that, functioning in reverse, defamiliarizes the rustic image: sofas in the street, in an open space. A collection of second-hand sofas has been gathered and put reuse in this place. Mostly, these movable three- or four-person sofas help to strengthen the western border of the courtyard, of about 10 meters long, and when placed on the asphalt edge of the street/square, they bring a sense of security and privacy to the lowered ground of the courtyard. The presence of furniture that usually belong to the domain of the domestic interior space in the outside open space creates a bit of surreal shock and to some extent generates an urban rendering of the space. The notable scale of the lengthy row of sofas can be seen from afar inviting the stranger to come and have a look. The portable aspect of the sofas equips the place with flexibility and the sense that there are possibilities to change the space depending on the needs and situations, or perhaps resulting in the involvement of others with more of them engaging responsibility in sustaining a sense of family or community.

The furniture conveys a symbolic meaning as well: the feeling that we are in the interior of a living room or in a private courtyard while actually being in the public space of a city. Yet, the fact that we are aware this vital space is in the middle of a site of demolishment and ruins, and of suspended time, creates a surreal sense that makes us buy Amou-Abbas’ words that the people and spaces of Nafar-Abad are one and are inseparable. The secure and homey image that the courtyard represents challenges the general assumptions of alien tourists whom by chance come and take a look at a semi-ruined neighborhood located on the southern margins at the end of an endless megalopolis. However, we should not forget that part of the relative sense of security felt in this area is thanks to the presence of the Holy Shrine.

Hence in this particular “Hashti” of Tehran, at the border between the urban and non-urban, at the crossroad of different landscapes (agricultural and industrial versus religious and residential) is where many contrasting things coexist with intensity: the Holy Shrine and Nafar-Abad, development and ruins (destruction), cemetery (the dead) and settlement (the living), inside and outside, private and public, indeterminacy and hope, the courtyard and the square, a sense of place and placelessness, structure and agency, past, present, and future.

BIO

Kaveh Rashidzadeh (b.1981) holds a PhD in Urbanism from the IUAV of Venice, is an architect and urban planner, assistant professor, and the head of department of urbanism at the IAU South Tehran branch. He has previously studied in TUDelft, UT, and SBU of Tehran. His research focuses on mapping the spatial and historical aspects of geographies of evils in societies.

References

Masjed-Jamei, Ahmad. 2013. Tekkieh of Nafar-Abad as the oldest Tekkieh of Tehran [in Persian], Iran daily newspaper, no.5517, p.13.

Torabi Kachousangi, Fatemeh. 2014. Historic Religious Identity, Ray Urban Dignity: Searching planning perspective at the neglected historic religious district to revive the local quality as a promoter of urban cohesion in different scales. Master Thesis, TU Delft University of Technology, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Urbanism.

“ Nafar-Abad.”, 35°34’54.94” N 51°26’08.84” E, GOOGLE EARTH PRO, CNES 2016/Astrium, accessed June 2016.

“ Nafar-Abad.”, 35°34’54.94” N 51°26’08.84” E, GOOGLE EARTH PRO, Digital Globe 2016, accessed June 2016.

*Cover photo: Picture of a niche inside Amou Abbas's house, and a niche from the ruins one block away. (c) Kaveh Rashidzadeh , 2016

[1] Meaning Uncle Abbas, which is his nickname the people of the neighborhood know him by. His real name as well as the name of the consulting firm that has produced the development project for Nafar-Abad will not be mentioned in this essay.

[2] Descendant of an Imam in the Shiite religion.

[3] “Commission of Article 5 of the Iranian Supreme Council for Architecture and Urban Planning defines the decayed areas as including weak and instable buildings, narrow paths, small houses, the structures that the possibility of helping them at the times of the natural and other disasters is low and consequently the effects of such disasters on them are very high” quoted from Emadi, A.H. Et al. 2014. Pathology of Rehabilitation of the Urban Decayed Areas Based on Public Participatory Approach in Iran, Journal of Social Issues & Humanities, Volume 2, Issue 10, October 2014.

[4] “Action” or “act” here refers to my attempt to link the historical norm of behavior of Persian artists (painters, architects) to reduce their pride in showing modesty when signing their work by stating “act (amal in persian) of this trivial minor (name of the artist)” before mentioning their names. There are even many examples of good works of architecture without knowing who the architect was. I used the word act to, on the one hand, state that Amou-Abbas is an environmental designer (artist) in his own terms, so I could avoid using the modern word “design” and relate it to the act of a builder as well. On the other hand, we can refer to the fact that it was his action/act to do something at the best of his abilities to make a change, to reshape his environment that is important.

[5] Urban may not be completely true in the sense that both elements that constitute this space and the usage of it do not correspond to the contemporary sense of the word urban. In any case, the location is in Tehran, and therefore it breathes an urban air.